Education

The Death of Authority in the American Classroom

“I learned ancient Greek just so I could read Aristotle in his own language.”

It was early in the fall semester of my freshman year of college and we were reading a passage from Aristotle’s Politics in a political philosophy seminar. In addition to learning Aristotle’s view that man “is a political animal,” this divulgence from my young, first-year professor was neither a verbal thunderclap nor a haughty declaration. It was an offhanded remark, uttered as a trivial aside. As usual, he radiated confidence without the slightest hint of ego. His mastery of Greek wasn’t a topic of conversation among my classmates and no one ever mentioned it again. And yet, almost 30 years later, I can still recall experiencing a subtle pulse of enthrallment.

Granted, it did seem a little odd to my 18-year-old self. Was Aristotle so earth-shattering and profound he merited this type of Herculean effort? I was too ignorant at the time to be impressed. I didn’t know until much later how much harder Greek is to master than Latin, with its mercurial alphabet, foreign declensions, unique conjugations, and Byzantine rules of grammar. I now understand why people devote years of their lives in pursuit of this particular linguistic treasure from antiquity. And not just to read Aristotle. Goethe considered Homer to be superior to the Gospels.

Of course, not all the teachers from my youth were this impressive. Most were forgettable. Teachers try to make an impression, but as the decades pass most of our teaching moments are mentally tucked away into a few fleeting images. Our students might remember who wrote the Federalist Papers or how to write down the Pythagorean theorem, but that doesn’t mean they remember the moment they learned it or who taught it to them.

Still, most teachers radiated a genuine sense of authority. Children, by and large, once looked to their elders for answers to their most important questions. They did so for a simple reason: adults were recognized as depositories of guidance, or even wisdom. They knew what a youthful mind needed to master because they, too, were once young. In the course of life, adults had fallen in love and knew about rapture, longing, and the many ecstasies and agonies of the heart. They had made friends and lost friends and occasionally eulogized their friends. Many fought in bruising wars, marched against injustices, and still sensed the goodness of American idealism. They climbed mountains, walked trails, read dense books, memorized impactful poems, and knew what it meant to aspire and dream. They had first-hand experience with frailty of the body, myopia of the mind, and hubris of the spirit. They could detect the difference between true leadership and empty demagogy. They knew what was truly important, what was genuinely frivolous, and appreciated the scarce commodity of time.

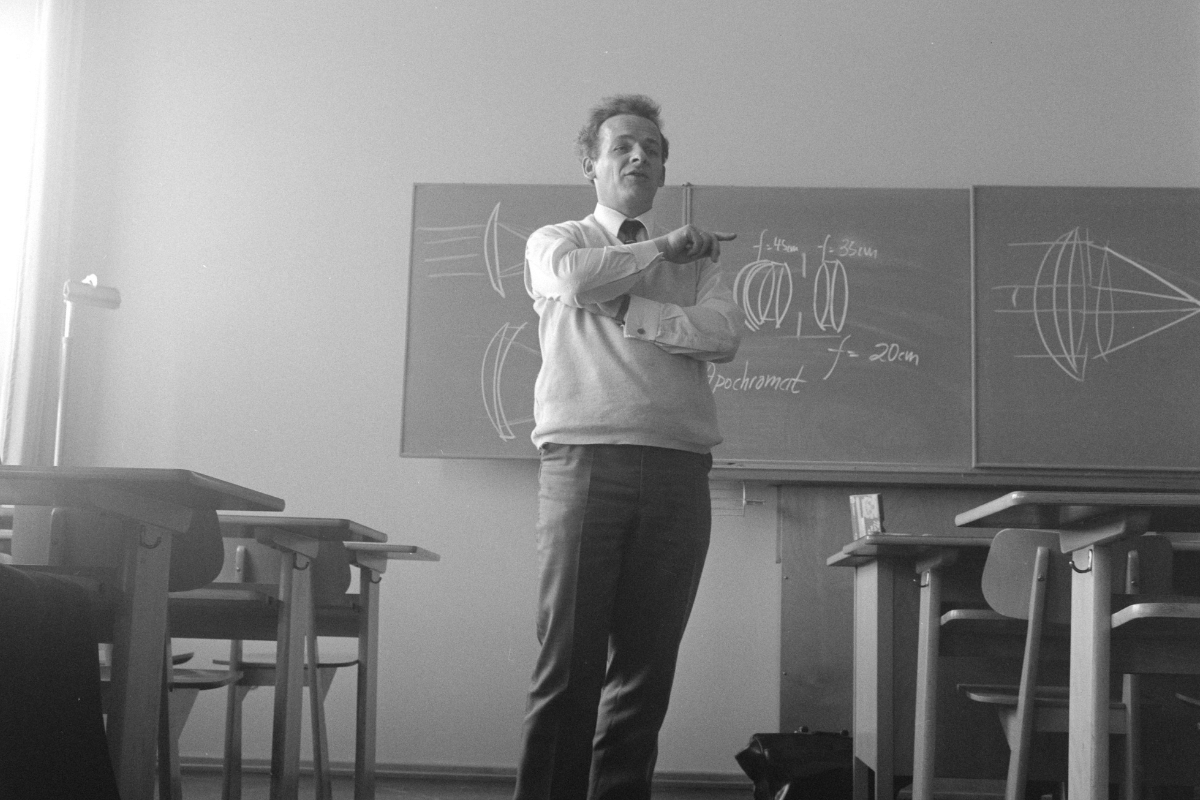

As they aged, these adults sensed the seriousness of life. They recognized answers were “out there,” in the nectar and lemon juice of life, in the grasp of adventure and endless engagement—the answers were never found in the monotony of petty amusements or the prison of mindless distraction. But most extraordinary, if these adults happened to be teachers, they drew on their lives to bring the classroom to life. This is what the best teachers always do.

There are extremes, of course. When famed Yale English professor Harold Bloom died a few years ago, it was fondly remembered that he had all 10,000 lines of Milton’s “Paradise Lost” committed to memory, word for word. Conservative political theorist Harry Jaffa supposedly had a memory that was nothing less than encyclopedic, capable of retrieving long passages of dense texts from books he had read decades earlier.

In my own educational journey, there were plenty of impressive teachers who radiated authority without having to master ancient Greek or memorize the entirety of a canonical text. My freshman English teacher in high school, who also happened to be my father, could diagram complex sentences and had long sections of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar memorized. Many of my professors in college were respected scholars in their academic fields. The president of my university was a world-renowned expert in the work of Danish existential philosopher Søren Kierkegaard. Authority was not in short supply.

Which is why I remember feeling a strong and buoyant desire as a student to impress these men and women. I wanted to contribute meaningfully to a class discussion, or write a cogent paper, or elicit a laugh during office hours. I wanted more than just a good grade or empty praise; I wanted them to see me as substantive, praiseworthy, and laudable. I wanted to earn their approval and affirmation, not because it was owed, but because it was freely given. I would have done almost anything to avoid disappointing them. As Adam Smith wrote in the Theory of Moral Sentiments, “To a real wise man, the judicious and well-weighed approbation of a single wise man gives more heartfelt satisfaction than all the noisy applauses of ten thousand ignorant though enthusiastic admirers.”

A sinister replacement

Modern education has replaced authority with empty adoration. It now encourages “ignorant” and “enthusiastic” admiration of children who frankly do very little to earn it. We have a lot of “noisy applauses” but precious little “well-weighted approbation.”

What caused the death of authority in the classroom? The answer is really quite simple: both the teachers and the students. In the time since I first started teaching over two decades ago, a radical reformulation has taken place in our midst.

The educational universe has slowly tilted away from its original mission of transforming and improving the inner fiber of young people. It used to be understood that because life is difficult, because success is fleeting, because relationships are enigmatic, and because our bodies and minds constantly disappoint us, a good life requires strength in all of its forms—moral, physical, intellectual. It is why character is destiny. It is why high expectations are a blessing. Life is tragic, yes, but that doesn’t mean it has to be a tragedy. We can successfully confront the world by improving ourselves.

While certainly not as important as the home or the chapel, the classroom used to be an important ingredient in the shaping and eventual ripening of a young person’s inner nature. Until quite recently, the world and the broader universe itself were considered fixtures to confront, not canvases to improve. As Roosevelt Montás writes in his recently-published book Rescuing Socrates, education “begins from the premise that the fundamental issues facing a student are not scholarly but existential; its basic mission is not epistemological but ethical.”

However, this view is now passé in the world of therapeutically politicized education. Now, instead of changing what’s inside our children, we are expected to alter and soften the outer world they have to confront. We are expected to make the world as pleasant and simple and amenable as possible. The role of a teacher is no longer to inculcate habits and standards that would empower a young person to live successfully in a broken, unfair, and tumultuous world. Our role is largely emotional in nature. We want our students to feel good about themselves. We want the classroom to cultivate wellbeing. We provide social services and endless accommodations. We have convinced ourselves that self-esteem rocks the cradle of academic achievement.

In short, classrooms have become emotive enclaves of a stark student-centered universe. This pivot towards the teacher-cum-protector role has colossally diminished the authority of the everyday classroom teacher because it has transformed the way students look at us. They are difficult to impress these days because the things that once commanded respect and imbued authority—intellectual achievement, virtuous behavior, classroom dynamism, prodigiousness, substantive life experiences—no longer attract the high regard they once did.

Look around campus these days and it is not rigor and pedagogic élan that shine—it is chic activism and avant-garde teacher attitudes parading themselves as classroom instruction. This is one of the main culprits behind parental frustration with the American education system. It explains why so many parents are up in arms, confronting school boards, with interest surging in charter, parochial, and classical schools.

What has modern teaching been reduced to when authority is deadened and diminished? We certainly don’t change lives in the way we used to. There are a lot of projects. A lot of group work. A lot of open note tests. A lot of extensions and pleas from counselors begging teachers to be endlessly empathetic and unabashedly lax. Nowhere do we say that a classroom can be a place where benign antagonisms flourish and take root, where there is nothing unhealthy about a student wanting to impress the teacher or feeling embarrassed by poor behavior or shoddy effort.

Instead, we entertain, we utilize cutting-edge apps and technologies to deliver curriculum, we quietly advocate for our favorite social causes, we cultivate meaningless “aptitudes.” Young Americans are nowhere confronted in their lives by any vestiges of traditional authority—the humanistic authority of literature, the intellectual authority of philosophers and scientists, or the interpersonal authority that radiates from someone standing in front of the classroom claiming to know what is essential, authentic, and necessary to attain any measure of genuine flourishing.

The advent of new and useless oracles

So, where do our children turn for life advice or if they want to stoke the embers of meaning or entertain the vast possibilities offered by their own lives? Where do they acquire the inner resolve to succeed in a difficult and menacing world? What oracles of insight and perspicacity are readily available? Parents are often working or distracted by their own devices. Most young people would never seek out a pastor or rabbi or spiritual advisor. They rarely read books or consume art. And so, they turn to other young people.

For all the evidence that excessive social media consumption isolates and depresses young people, it shouldn’t be forgotten that a corollary to this misery is that it also strands them in an echo chamber dominated by other youthful voices and perspectives. They often spend nine or 10 hours a day in this echo chamber. It is an infinite feedback loop of fetid content, much of which fetishizes outrage and elevates all that is wrong with the world. If our children believe they live in a thoroughly racist-sexist-classist-ableist society that is on the brink of collapse because of rising global temperatures, it is probably because they have seen thousands upon thousands of algorithmically cued-up videos, all attesting to various incarnations of imminent doom.

Adults wonder why young people are so cynical. We wonder why they speak in memes. We wonder why they are so miserable and depressed and friendless and bereft of meaning in their lives. But we can’t blame it all on Silicon Valley. It is also because we have offered them no academic or personal avenues to discover genuine purpose and grandiose meaning. We tell ourselves homework is old-fashioned and unnecessary. We let them abandon Shakespeare for the macabre world of YA fiction. We have allowed them to cloak selfishness in capes of heroic individualism—to discount the importance of institutions, commitments, and traditional pillars of adult life. We have refused to be authorities because we knew authority itself was not consistent with the radically individualized worldview of American youth culture.

Why did we do this? Because those of us who knew better decided instead to win their approval. We did this not by stepping into a child’s circle and offering guidance or insisting on standards, but by telling young people they should become more independent, more autonomous, less tethered to the ideas and expectations of those who came before. It is why colleges encourage students to “design their own major” or why it is fashionable to insist that students “see themselves” in the books they read, as if the point of literature is affirmation instead of inspiration. We have channeled the worst of Rousseau and deified Dewey’s pragmatism. We have let children decide what to put in their intellectual quivers and are shocked when they have no idea how to shoot an arrow.

Instead of explaining what we know and how we know it, we merely capitulated to the desire to be liked. This is why our children are so susceptible to every moral, intellectual, or spiritual fad that appears on their screens. We let them believe that truth is artificial, love and friendship are power constructs, all religion is a mental phantom, and history is pure narrative. We stopped harnessing our authority to insist our children do the reading and thinking that would lead them to appreciate that truth can orient life, love, friendship, and faith are all worth living (and sometimes dying) for, and history is not just the biased tale of the winners.

The clipped wings of our children

Goethe once wrote, “There are only two lasting bequests we can hope to give our children. One of these is roots, the other, wings.” The death of authority in the classroom means we have stopped watering roots, and in the process, clipped their wings.

But just how low do our children fly nowadays? Consider a situation that has become far too frequent in the lives of modern teachers at virtually all levels of instruction. The reaction from students who are caught cheating or plagiarizing is revealing. Frequently, students who are caught red-handed will deny they cheated in the first place. If they do admit to it, they often justify their mistake by saying other students cheated as well. Sometimes, they will cite a disability or anxiety as a culprit for their misbehavior. In some cases, a plagiarizing student will outrageously claim it is not cheating at all to copy someone else’s work since the student had to sit at a computer and re-type the words.

Outsiders to the classroom might find these disquieting episodes to be the stuff of bad fiction or an off-beat Hollywood screenplay. But if the moral framework of our children reeks of relativism, what are we to make of the behavior of their parents? What excuse do we have for high-school counselors and college deans who plead with teachers and professors to exercise “extreme empathy,” who argue any negative consequence is punitive and therefore harmful to the student in error? This is how we justify bad behavior on campus—the non-stop cursing, the TikTok challenges, the drug use, the defiance, the resistance to deadlines. It says something sinister and cynical about all of us that our reaction to poor behavior is not to construct policies that incentivize a different and better path, but instead to couch our lower expectations in the membrane of “compassion” and then pat ourselves on the back for doing it.

At its best, authority lays the groundwork for how to live and endure, how to think and feel, how to impact the world in a positive and ennobling fashion. Classroom authority is not a pretext for punishment. It is a prerequisite for human growth. It is the sunlight that illuminates the darkness of youth. It is how every person can eventually find his or her wings in this life.

Proust was certainly correct when he wrote, “We do not receive wisdom, we must discover it for ourselves, after a journey through the wilderness which no one can make for us.” But he left out the central truth that all good teachers understand: one of the greatest joys of life is sharing what we discovered in our own wildernesses. For if our emergence from the wilderness does anything at all, it imbues us with a sense of authority. It is the wilderness of war or cancer or divorce that colors the most potent insights of human suffering. It is the wilderness of ineffable joy and enigmatic inspiration that colors the highest peaks of human potential.

Adults have authority not because they are adults, but because the arrows and agonies of life spare none of us. We know because we have endured, we’ve “been there,” we have experienced an electrifying ripening of the soul. Distancing our children from authority is not love and it’s not compassion. It’s a cruel impoverishment of the human spirit.