India

Next Year in Simla: Thirty years After Its Defeat, the Khalistan Movement Fights on in Cyberspace

Even if the referendum turns out to be a complete failure, though, the Khalistanis seem unlikely to fade away.

The death threats have definitely gone upscale. Fifteen years ago, they were quite uncouth. As one put it: “time to find out where Milewski lives and put his head on a stick.”

Over time, though, they’ve become a little more polished.

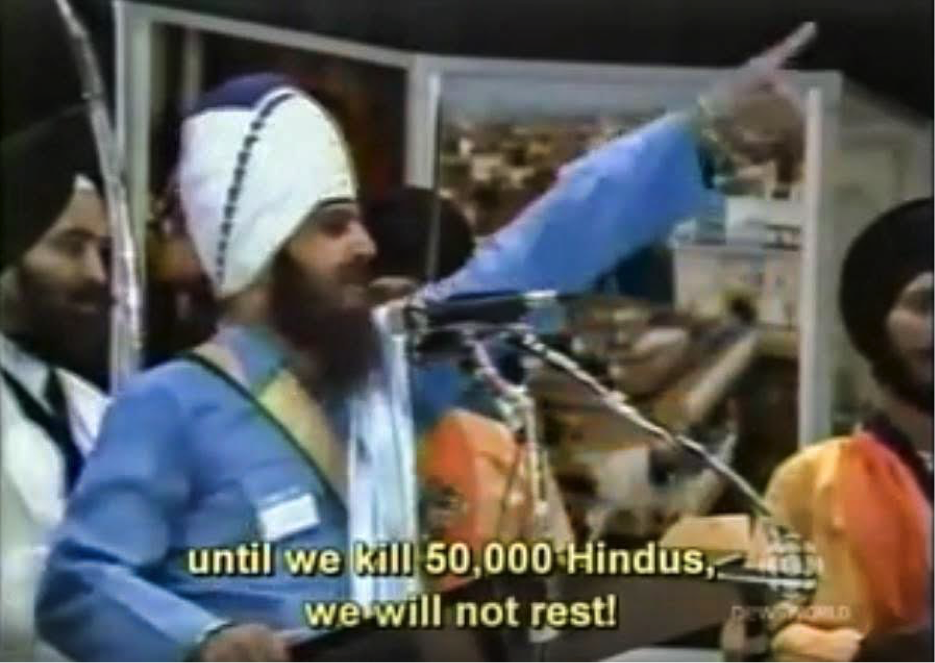

Okay, the little gun needs no translation. But you’d have to know Gurmukhi script to decipher the rest. It says, Lala Jagat Narain. That’s the name of a Punjabi journalist and editor who criticized Sikh extremist Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale (1947-1984), the patron saint of the Khalistan independence movement. For that, Narain was shot dead in his car by two goons in 1981.

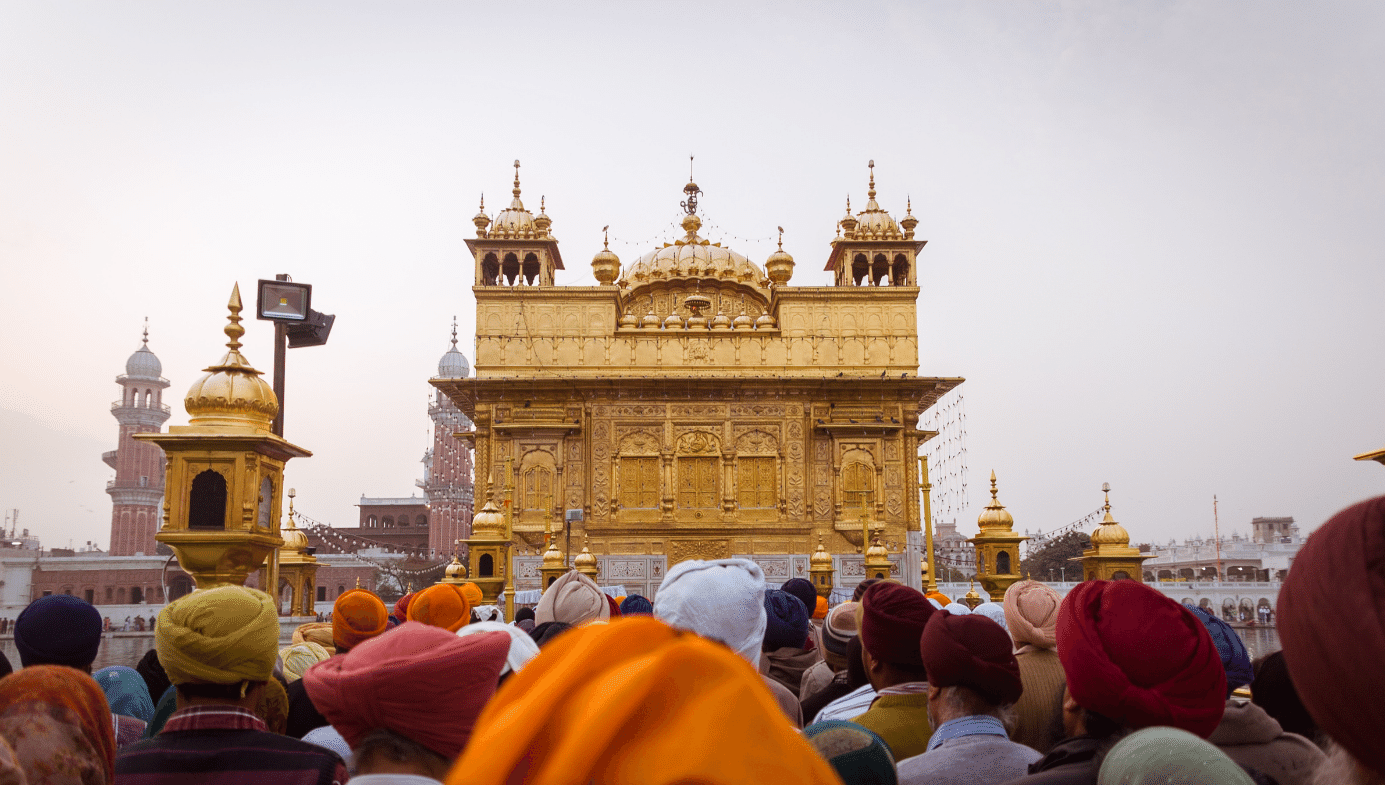

Bhindranwale was arrested as the prime suspect. His followers then hijacked a plane. He was released, but defied the government by turning the Golden Temple at Amritsar, the preeminent spiritual site of Sikhism, into an armed camp. He was martyred there in 1984, in an Indian Army raid that ignited a decade of bloodshed.

So, nearly 40 years after Lala Jagat Narain’s murder, a young Bhindranwale admirer thought to remind me of Narain’s fate—perhaps because I’d written that month about the separatist movement’s faltering efforts to revive itself. Once again, a journalist was in the gunsights. The six retweets suggest that the idea didn’t exactly set the Internet on fire, but there does seem to be a new generation of Khalistanis who see a critic and think about violence.

Sant Jarnail Singh Ji Khalsa Bhindranwale, the man who awoke a nation ❤️#BattleofAmritsar1984 #Panth #JangHindPanjab #Sikhs #gallantdefender #khalistan #khalsa #10daysofterror #santjarnailsingh #operationBlueStar pic.twitter.com/cjcC3tLwmW

— ਰਣਵੀਰ ਸਿੰਘ । Ranveer Singh (@RanveerSP) June 1, 2021

The author of that unsettling tweet, Ranveer Singh, is the co-founder of the National Sikh Youth Federation in the UK. The name echoes that of the International Sikh Youth Federation, long since banned in India and elsewhere. Today, the struggle for Sikh sovereignty is mainly digital, but is supercharged by a strident online campaign for an unofficial, non-binding referendum on a separate Sikh state—Khalistan—meaning, Land of the Pure.

The new nation would comprise a large swath of north-western India, with its capital at Simla, the old summer retreat of the British Raj in the Himalayan foothills. The campaign to create Khalistan is now being led primarily by a US-based group called Sikhs for Justice, which is banned in India. Nevertheless, voting in the so-called “Punjab Independence Referendum” began for Sikhs overseas in 2021, starting in the UK on a significant day: October 31st. That’s the anniversary of an even more famous killing—the 1984 assassination of India’s prime minister, Indira Gandhi, by two Sikh bodyguards who were out to avenge the raid on the Golden Temple. In the days after her murder, thousands of innocent Sikhs were massacred by mobs in Delhi and elsewhere—a bloodbath that rightly shocked most Indians, including the broad mass of patriotic Sikhs who wanted no part of the separatist cause.

About 21,000 lives were burned up in the next 10 years of Khalistani insurgency, which spread far beyond India. In June of 1985, the Babbar Khalsa terrorist group in British Columbia checked in two suitcases of dynamite on planes leaving Vancouver airport, one flying east and one west, each connecting to Air India flights. The two owners of those bags never took their seats.

The westbound bomb blew up at Narita airport near Tokyo, killing two baggage handlers as they moved it to the target flight. An hour later, near the Irish coast, en route to London, the other bomb destroyed an Air India jumbo jet named for a second century Kushan emperor, Kanishka. Three hundred and twenty-nine lives were extinguished at a stroke. Most were Canadians of Indian descent, including 33 Sikhs.

It was the deadliest terrorist attack anywhere until 9/11—and it did nothing to bring the creation of Khalistan any closer. Even so, the resilience of the separatist cause is evident in the extraordinary fact that Talwinder Singh Parmar, the leader of the Kanishka massacre, is still publicly honoured as a martyred hero by Khalistani diehards in Canada and beyond. Posed as a soldier-saint with sword in hand, the image of Talwinder Singh Parmar is permanently fixed to an important Sikh temple in British Columbia. He was even chosen as the poster boy—literally—in the current Sikhs for Justice referendum campaign.

As grotesque as it may seem for a mass-murderer to be glorified in this way, the spectacle has long since been normalized in Canada, which is home to about half a million Sikhs. Political leaders tiptoe around the issue for fear of alienating an important voting bloc. A common excuse is that Parmar was never convicted for the bombing—although that’s because he didn’t live long enough to stand trial. He fled Canada for Pakistan, and was killed in 1992 by police in Punjab. But his bomb-maker, Inderjit Singh Reyat, was convicted; and a series of criminal trials, followed by a judicial inquiry, left no doubt that (as Reyat himself confirmed), he made the bombs for Parmar.

Reverence for martyred murderers seems to be central to the revival of the Khalistan cause in cyberspace, and seems especially belligerent in the case of Parmar. Unlike other martyrs who killed enemies of the separatist project, Parmar killed hundreds of civilians who had nothing to do with his struggle. More than 80 were children.

Just as hard to explain is that his fans seem to be split between those who pretend he was wrongly accused and those who acknowledge that, sure, he did it—but that’s okay because he was a freedom fighter.

In the latter camp is the Program Director of the so-called Khalistan Centre, Shamsher Singh, who is also a co-founder with Ranveer Singh of the National Sikh Youth Federation.

It was Shamsher Singh who posted some truly jaw-dropping comments on the Air India bombing in March of 2018. He declared on Twitter that he was privy to inside information concerning the intentions of Parmar’s Babbar Khalsa bombers, and the timing of the bombs. Some un-named BK members had confided, he said, that the eastbound Air India bomb was timed to explode on the ground, like the one that went off in “Hong Kong.” (Presumably, he meant Tokyo, just as calling the plane “Kansika” was presumably a typo for “Kanishka.”)

Shamsher Singh also alleged that the Indian government somehow knew there was a ticking bomb on Flight 182, and also knew when it was set to go off—but delayed the flight to make sure it exploded while still aloft.

Recently, Shamsher Singh has made his tweets private, without answering the many questions that his astonishing comments invited. For one thing: Who confesses on Twitter to knowing the minds of terrorists who were never identified by the police? (Except for Parmar, Reyat refused to name his co-conspirators, so Shamsher’s claimed knowledge could have been crucial at trial.) Who were his sources? How did they know about the timing of the bombs? How did they know that “India” also knew and delayed the flight? Why did Shamsher Singh not reveal all this and testify?

One possible explanation is that it’s all nonsense. The same applies to the question why, if the Indian government knew of the bomb, it would welcome its explosion. Shamsher Singh evidently adopts a grossly incoherent “Air India Truther” theory—that the tragedy was a “false flag” operation to discredit the separatists, paralleling the claims of 9/11 Truthers, who believe the September 11th, 2001 terrorist attacks were an “inside job.” In both cases, the conspiracy theorists sub-divide into those who think the real evildoers—led by George W. Bush in the 9/11 attacks and by the Indian government in the Air India bombing—(a) perpetrated the attacks themselves and then blamed others, or, (b) knew of the plot but did nothing to stop it, or even encouraged it, to serve their geopolitical agenda.

There’s no evidence that either theory is true, and two insuperable problems arise in the case of Air India. First: discrediting the separatists would have been easily accomplished, without the loss of the passengers or the aircraft, if the Indians had simply exposed the plot before it played out. And second, there was no shortage of massacres in India to make the separatists look bad. Their death squads firebombed markets, machine-gunned passenger trains, shot Sikh policemen and their children, pulled Hindus off buses to be murdered by the dozen and swore to burn alive Sikhs who did not obey their orders. With thousands dying in India, why would a few hundred Canadians need to die to make the Khalistanis look bad?

Besides that, why had the Indian government—the owner of the airline—warned Canada about a crescendo of terrorist threats and pleaded for extra baggage security? Was this to stop their own bomb?

Challenged about his tweet, Shamsher Singh cobbled together a second tweet that was just as unsettling—insisting that, “clearly the casualties were unintended during a time of war.”

“Unintended”? “Time of war”? This wasn’t clear at all. The Canadian victims were not part of any war. Besides that, the bombs were checked in intentionally. If you put a bomb on a plane, you know the passengers may die. That’s why the men who checked in the explosives never boarded the aircraft.

But Shamsher’s final point gives the game away. It’s a macabre word game: He declares that the bombers were part of a “liberation movement,” and so—presto—they weren’t terrorists. Besides, to call them terrorists “erases Sikh lived reality.” Needless to say, this woke jargon does not change the facts: the “lived reality” that was actually erased was that of the 331 innocent victims.

Shamsher Singh’s tweets provided a rare glimpse into the thinking, if that’s the word, that guides the little-known subculture of Khalistan true believers. This backwater of the Internet attracts little interest from the outside world, even when heaping praise upon a notorious mass-murderer such as Talwinder Parmar. In a rambling online screed published by the Khalistan Centre, called Who Speaks For Khalistan?, Shamsher Singh’s group bestows layers of honorifics upon Parmar: Shaheed, Jathedar, Bhai—martyr, religious leader, brother—but contrives never to mention Parmar’s only achievement: the Air India massacre. Forty-eight pages roll by with no hint as to what on Earth Parmar did in his life to earn such respect. Once again, his victims are erased.

Forgetting the victims and praising their killers does seem to be standard procedure among many of Khalistan’s keyboard warriors. Consider another tweet from a British Sikh, this one with a formidable 335,000 followers.

On the face of it, it’s a sweet tweet. It tells the heart-warming tale of Ravinder Singh, who’s been given a fancy Swiss watch. Alas, he cannot accept it. So, he gives it to the son of a fallen hero in the Sikh independence struggle. Cue applause.

Of course, there’s more going on here than meets the eye. Ravinder Singh—that’s him on the left—is the founder of a Sikh charity called Khalsa Aid. But his tweet wasn’t really about charity. It was a signal of solidarity with the Khalistani faithful. Nobody else would have a clue what the reference to “Shaheed” Major Singh Nagoke was all about.

The answer is simple: He was a serial killer—a hitman for Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, the aforementioned preacher who barricaded himself in the Golden Temple, surrounded by his gunmen. Bhindranwale’s enemies tended to turn up dead, as in the case of journalist Lala Jagat Narain. But both Bhindranwale and Nagoke died, too, in the Indian Army’s raid on the temple in June of 1984.

Nagoke had won high status in Bhindranwale’s entourage by arranging the death of the guru of a rival Sikh sect deemed heretical. But it doesn’t stop there. Nagoke’s son, Ajaypal, proudly says in this Punjabi interview that his father was also the marksman in the notorious shooting of a senior Punjab police officer, A.S. Atwal, after praying at the Golden Temple in 1983. The killing shocked Punjab when it was learned that Atwal’s body was left to rot in the sun because his men dared not venture onto Bhindranwale’s turf to collect it.

When the army did invade the temple a year later, Nagoke, his son says, was also a party to the grisly death of an army doctor. As the troops mopped up the last of Bhindranwale’s holdouts, he says, Nagoke accepted the army’s offer to send in a medic to help the wounded. Instead, that doctor was hacked to death.

Ajaypal even claimed that his father narrowly missed shooting the only Sikh President of India, Zail Singh, but killed the president’s bodyguard instead. Such are the services that earned Nagoke the title of “Shaheed” and the notice of Ravinder Singh, whose above-pictured tweet on December 8th, 2021, gathered about 2,000 likes.

All of this serves the Khalistanis’ drive to paint their movement as both militant and enduring. They also paint the Indian state as fascist and genocidal, and Ravinder Singh is active on that front, too. Six weeks before posting his tweet about Nagoke, he accused hundreds of millions of Indians of conniving to ignore a campaign of rape targeting the Sikhs of Punjab. “Most of India” knew that such rapes were a “common practice” by “Indian police,” he said—allegedly as a means to punish the families of “political activists” in the heyday of the armed struggle.

During the 1980s rape was used as a tool by Indian Police across Panjab . It was common practice by the police to detain the families ( including elders) of the political activists and rape the women in front of their families.

— ravinder singh (@RaviSinghKA) October 25, 2021

Yes, I am angry!Most of India knew & kept silent

As they say on Twitter, big if true. But evidence of the alleged rape campaign seems strangely absent from the historical record—stranger still given the fact that this record is otherwise brimming with details of (real) police abuses.

There’s no doubt that the fighting in Punjab was extremely vicious. The victims were mostly Sikhs, as separatist militias imposed their puritanical dictates and fought the Punjab police, two-thirds of whom were also Sikhs. Credible reports, based on hundreds of witness interviews conducted by sources such as Human Rights Watch, Asia Watch, Physicians for Human Rights, Ensaaf, and Amnesty International, all describe atrocities being committed regularly for more than a decade. These include massacres of both Sikh and Hindu civilians by Khalistani gunmen, as well as beatings, torture, and extrajudicial executions by the police. All of these abuses were recurring, organized and known to superiors on both sides.

Yet these grim reports do not describe any program of rape by the police, much less one that was known to most of India. Countless eyewitnesses either did not see, or forgot to mention, the appalling scenes alleged by Ravinder Singh to have been common.

A landmark 1994 report by Human Rights Watch, for example, makes no mention of rape at all—although it gives abundant names, dates, and places in regard to sickening brutality and killing by the police in Punjab. Likewise, a 2009 study by Ensaaf, which collated vast amounts of data on these abuses, says nothing about rape.

There were undoubtedly rapes, both by police and by separatists. But there’s no obvious reason why human-rights investigators would record pages of details about murder and torture by the police, yet cover up a “common practice” by the same police of raping relatives of Sikh militants, whether in front of their families or not.

Ravinder Singh’s tweet, then, provoked some challenges. One that seemed to sting came from a Sikh in New York—a scholarly type named Puneet Sahani, who acts as coordinator for a Twitter account called “Sikhs for Enlightenment Values Association.” What happened next revealed that the Khalistani cyber brigade has some advanced skills when it comes to silencing critics.

Sahani’s fluency in Punjabi, his knowledge of Sikh history, and his penchant for enlightenment values made him a difficult online adversary. For Khalistanis, he was the enemy within, so he became a target of organized mass complaints designed to overwhelm Twitter’s system (if it can be called a system) for managing the huge daily intake of users’ pleas to gag their enemies.

Puneet Sahani saw Ravinder Singh’s tweet about rapes and set out to disprove it with a volley of quotes and citations. He quoted the veteran Khalistani political leader, Simranjit Singh Mann, on rival separatists who engaged in “abducting girls, raping the girls.” Sahani’s reply to Ravinder Singh also cited damning research on the militants by senior Sikh academics in Punjab, and linked to contemporary news reports quoting women abducted and married at gunpoint to Khalistani gunmen.

Sure enough, Sahani saw his account being mass-reported for “hateful conduct.” Oddly, Twitter’s response was to lecture him that its rules forbid attacks based on race, religion, etc., although Sahani did not criticize Singh on any of those grounds—only for saying things that weren’t true. But what mattered to Twitter’s computers was not what Sahani actually said, but the fact that large numbers of users didn’t like it.

Numbers, of course, are what computers are good at—and it isn’t clear that any human even glanced at the facts before Sahani was ordered to delete his “hateful conduct.” Evidently, accusing most Indians of winking at an official campaign of mass rape was fine, but citing evidence that they did not was “hateful.”

Sahani declined to delete his tweet. If he did, Twitter warned him, it would be an admission of guilt. So he stuck to his guns.

It didn’t work. Sahani’s personal account was also under attack. His enemies had figured out how to game Twitter’s algorithms. It turns out that if you want your critics thrown off Twitter, you go to specialists who can orchestrate a blizzard of complaints—enough to trigger an automatic trip to Twitter jail.

𝐂𝐚𝐬𝐞 𝐍𝐨 : 685

— Team Kisan United 🚜 (@TKUOfficial1) November 23, 2021

🅢︎Ⓤ︎Ⓢ︎Ⓟ︎Ⓔ︎Ⓝ︎Ⓓ︎Ⓔ︎🅳︎ @puneet_sahani

Thanks #TeamKisanUnited 🤝 #FarmersProtest pic.twitter.com/1imTZFNljy

Examples are Team Kisan United; and a Twitter account based in Mumbai (and now itself suspended) called “Team Real King,” which gaily profiled itself as a “Suspension Team,” and posted proof of its victims—the successful suspensions of hundreds of accounts. Indeed, both accounts seemed to exist on Twitter for the sole purpose of getting people kicked off Twitter.

When they were done, both Puneet Sahani’s personal account and his “Sikhs for Enlightenment Values” account were successfully hobbled. Team Real King took a victory lap, bidding him a cheery goodbye.

A telling detail is that Team Real King listed Sahani as an “Islam0ph0be,” although he’d said nothing about Islam or Muslims. In regard to his personal account, Sahani’s crime was thanking a follower who welcomed him back from a temporary suspension caused by a previous mobbing. Sahani told his admirer to beware the swarm that would punish him, too. That tweet was also labelled “hateful conduct.” The metaphorical locusts did, indeed, ensure that “David’s” account was suspended—along with other followers of Sahani. The “Suspension Team” was thorough.

This was hardly the first time that Twitter was played by mob-reporting. On December 3rd, 2021, the Washington Post quoted Twitter as admitting that it “mistakenly suspended” about a dozen accounts that had used photos in the public domain to identify far-right extremists. The aggrieved extremists, according to Twitter, had responded with a flood of “coordinated and malicious reports” targeting journalists who posted the photos, which, upon review, were deemed in the public interest.

Sahani, however, has not found any human to review his case or to admit any error. The computers are in charge, apparently. In fact, when I complained to Twitter that Sahani’s suspension was absurd, the automated system sweetly thanked me for reporting his hateful tweet and assured me that he’d been cast into outer darkness. Intelligence doesn’t get more artificial than that.

Khalistan hardcore’s supporters have not only shown themselves agile with Twitter, but also with the storm of videos and memes posted on Facebook by Gurpatwant Singh Pannun, the face and voice of Sikhs for Justice.

Pannun is the New York lawyer who’s running the referendum campaign, despite the fact his group has been banned by India (and Pannum has had numerous websites blacked out there). It was Pannun who came to British Columbia to announce the Shaheed Talwinder Singh Parmar Voter Registration Centre. The news was all over Facebook, too.

This display of reverence for Parmar is not an occasional phenomenon, nor a new one. Sikhs for Justice has long portrayed Parmar as “the great general of Khalistan’s war of freedom,” as illustrated with pictures of him hefting weapons during his three years as a gun-runner in Pakistan.

Sikhs for Justice calls itself a “human rights” organization. But the human rights of Parmar’s 331 victims are never mentioned in its propaganda. Nor are those of the 16 bystanders who died in the suicide bombing that killed Chief Minister Beant Singh of Punjab in 1995. Rather, the “human bomb” in that case, Dilawar Singh, was honoured with a Facebook video starring Pannun and entitled, “I Am Dilawar.”

The message of the “I Am Dilawar” video, released on the anniversary of the bombing, was that Chief Minister Beant Singh’s fate might also befall the then-chief minister, Capt. Amarinder Singh, a fierce opponent of the Khalistan movement. In case this wasn’t clear, Pannun showed a portrait of Capt. Amarinder being shot in the face by an off-screen gunman. Still not clear enough? Cue a closeup of the portrait being shredded by bullets. “Capt. Amarinder,” Pannun warns, “there is a writing on the wall.”

When Capt. Amarinder resigned and was replaced by another anti-Khalistani, Charanjit Singh Channi, the video was repurposed but remained just as blunt. Pannun warned Channi to “remember” the killing of Beant Singh—and jogged his memory with a shot of the smoking wreckage of Beant Singh’s car.

Another killing that’s a staple of SFJ’s publicity is the assassination of Indira Gandhi. The two Sikh bodyguards who shot her are honoured for their “brave act of justice.”

These messages, and many more like them, reflect Facebook’s willingness to host any number of groups posting and re-posting Sikhs for Justice material. Twitter, as we’ve seen, has also been hospitable to small Khalistani accounts (though it routinely takes down Pannun’s own, whenever he starts a new one, on request of the Indian government).

Even with their brief shelf life, however, Pannun’s interventions on Twitter have been educational. In June of 2021, he set up an account for the 36th anniversary of the Air India bombing, and posted an extraordinary letter to Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, demanding the expulsion of India’s High Commissioner to Canada, Ajay Bisaria—for the crime of condemning the bombing.

The High Commissioner’s statement that the Air India bombing “revealed to the world the heavy cost that Khalistani terrorism could inflict on humanity” was the focus of Pannun’s protest. He insisted the Khalistan movement was “peaceful and non-violent.” His complaint was that, by blaming “Khalistani terrorism” for the bombing, High Commissioner Bisaria was “hate-mongering against Canadian Sikhs.”

In fact, Bisaria never mentioned Sikhs at all, whether Canadian or not. But it’s standard procedure in separatist propaganda to conflate “Khalistanis” and “Sikhs,” as though all Sikhs are Khalistanis. Thus, any critique of Khalistani violence is held to be an affront to the entire Sikh community—falsely implicating all Sikhs in the violence. It’s a smear on the community that occurs routinely—akin to complaining that we must not condemn drunk driving, because that’s an attack on all drivers. In any event, after a flurry of tweets alleging that “thousands” of Sikhs had indeed demanded Commissioner Bisaria’s expulsion, Pannun’s account was shuttered.

Even so, his presence elsewhere on the Internet—outside India, that is—isn’t hard to find. In short order, he offered a $250,000 “bounty” for information on the movements of an Indian general under threat of assassination, urged Sikh soldiers not to fight against China, said he was “heartened” by the Taliban takeover in Afghanistan, and took a flame-thrower to the Indian flag.

Nevertheless, the chance that he and other Khalistanis will someday see the breakup of India still seems remote. In recent Indian elections, support for separatism among the Sikhs of Punjab has been extremely low—less than one percent. And, in the diaspora, the referendum has yet to garner significant enthusiasm. The most generous estimates suggest that barely ten percent of Sikhs living in the UK showed up to vote, and there are many questions about the validity of the figures. One British Sikh reported that he had no trouble registering to vote as “Angelina Jolie.”

Even if the referendum turns out to be a complete failure, though, the Khalistanis seem unlikely to fade away. They’ve survived worse, and have never relied on popular support. For 40 years, the vast majority of Sikhs has shunned them; their armed struggle has been smashed by the state; they’ve been banned and suppressed. Throughout, they have openly venerated a mass-murderer and many lesser murderers—moves that hardly seem calculated to win new supporters. And yet, the cause endures, attracts donations and heaps abuse on its critics. The Khalistanis are not done.

Instead, a changing world gives them hope. The movement is alleged to be supported by Pakistan, whose ally, China, is now busily giving India’s Himalayan villages new, Chinese names. Perhaps the existing borders might be changed? A new map of Khalistan produced by Sikhs for Justice envisions a sprawling nation, a hundred million strong, stretching from Rajasthan through Punjab, Haryana, and Himachal Pradesh, with added chunks of Uttar Pradesh and a capital at Simla.

Whether or not this dream ever comes true, the pronouncements of Khalistani advocates tell us plainly what methods they see as permissible in attaining it.