Canada

Khalistan’s Deadly Shadow

One brought down Flight 182, a massacre that remained, until 9/11, the deadliest terrorist attack in the history of aviation.

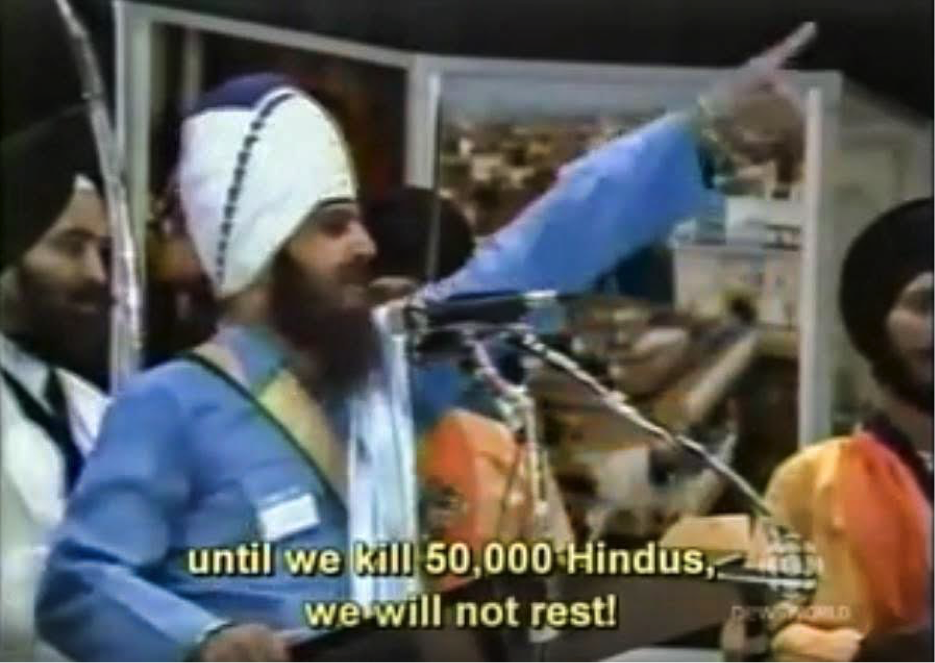

The New York City police officers looked bored, unable to understand a word, as they eyed the angry crowd at Madison Square Garden. A sawmill worker from the Canadian province of British Columbia took the stage with a retinue of robed warriors toting curved swords. He wore an ornate turban and sliced the air with his hand as he promised a massacre of Hindus.

“They say that Hindus are our brothers!” he declared in Punjabi. “But I give you my most solemn assurance that, until we kill 50,000 Hindus, we will not rest!”

In response, the crowd erupted in slogans: “Hindu dogs! Death to them! Indira bitch! Death to her! Blood for blood!”

“Indira” referred to Indira Gandhi, then prime minister of India. She lived for only three months after this scene unfolded.

It was July 28, 1984—the founding convention of the World Sikh Organization (WSO), created to carve an independent Sikh state out of India. The millworker, Ajaib Singh Bagri, was number-two in the Babbar Khalsa International, a terrorist group engaged in an armed struggle to win that state, to be called Khalistan, or Land of the Pure.

Bagri’s leader, Talwinder Singh Parmar—also a resident of British Columbia—was wanted for murder in India, and was therefore barred from the United States. So in New York, Bagri spoke on Parmar’s behalf.

Canada, though, did not bar either man. Both had been granted Canadian citizenship. Moreover, in 1982, the government of Pierre Elliot Trudeau had refused to extradite Parmar to India. So he was spared the need to stand trial for the killing of two Indian policemen, and was free to collect donations from Sikh gurdwaras, or temples, across Canada. There, he preached that 50,000 Hindus must die—the pledge that Bagri repeated in New York—and that “Indian planes will fall from the sky.”

Less than a year later, he kept his word. Air India Flight 182, from Toronto to New Delhi via London, was destroyed by a bomb while in Irish airspace. All 329 passengers and crew were killed. A Canadian commission of Inquiry concluded that the leader of the criminal conspiracy was none other than Talwinder Singh Parmar.

* * *

The Sikh faith, created in what is now northern India by the 15th-century Guru Nanak, remains obscure to many in the West. Turbaned Sikh men are sometimes confused with Muslims, and some have been assaulted by confused thugs following Islamist terrorist attacks. Like the United States, Britain and other Western countries, Canada has been home to emigrant Sikhs for generations—the vast majority of them living peaceably in their adopted homeland.

In the 1980s, however, a powerful spasm of separatist militancy shook India and spread to the Sikh diaspora. In June, 1984, two months before the Madison Square Garden convention, Prime Minister Gandhi and her government set out to end a killing spree by Sikh militants who had turned the Sikhs’ holiest site—the Golden Temple at Amritsar—into an armed camp. The Indian army wrecked the temple complex and took many lives. Revenge came on October 31, 1984, when Gandhi was gunned down in her garden by two of her Sikh bodyguards. Hindu mobs immediately took revenge for the revenge, slaughtering thousands of Sikhs in hellish reprisals that were aggravated by official complicity. The police looked the other way. The horrors of 1984 won’t be forgotten by either side.

Soon, Canada and its Sikh community were dragged into the thick of the struggle. In June of 1985, Parmar’s Babbar Khalsa placed suitcase bombs on two planes leaving Vancouver. One brought down Flight 182, a massacre that remained, until 9/11, the deadliest terrorist attack in the history of aviation. The second bomb, intended to destroy another Air India plane simultaneously, exploded on the ground at Narita Airport in Japan, killing two baggage handlers. The reverberations from the attack were so profound in Canada that even today, 33 years later, a striking emblem of the Khalistani dream survives: a large “martyr” poster honouring Talwinder Parmar, sword in hand, permanently fixed to the exterior of an important Sikh gurdwara in Surrey, British Columbia. Tens of thousands gather beneath it each spring for an annual Sikh parade. In American terms, the poster is equivalent to a public veneration of Osama Bin Laden.

* * *

Air India Flight 182, a Boeing 747 named for the second-century Indian emperor Kanishka, had just checked in with Shannon airport on the west coast of Ireland when the dynamite-based bomb exploded. On a terrifying tape from air traffic control, a strangled cry is heard as a blast of wind seems to hit the pilot’s microphone. Then, silence. The Shannon controller tries to keep calm as he hails Air India again and again.

“Air India 182, Shannon … Air India 182, Shannon.”

It’s no good. The controller hails nearby flights, asking them to look around. In disbelief, an American pilot asks, “Do you have him on radar?”

“Negative.”

Nobody sees anything until hours later, when Irish sailors are sent out to gather bodies floating in a sheen of jet fuel. (Some of the sailors still lose sleep over it.) One of the first bodies found was that of an elderly Sikh with a long beard. A ghastly and mercifully blurred piece of video, taken inside a rescue helicopter, shows the corpse of a small child being winched up from a grey sea.

But only 131 bodies were recovered. The Kanishka’s passengers and crew had been obliterated at 31,000 feet as Capt. Narendra Singh Hanse—a Sikh and a former pilot for Prime Minister Gandhi—prepared to descend over the Irish coast towards Heathrow. Most of the dead were Canadian citizens of Indian descent, travelling to visit relatives. They included not only Hindus, but also Muslims, Christians, dozens of Sikhs and 86 children.

Today, the parents who lost their children are old, the orphaned children have their own children and the Sikh struggle for independence is moribund in India. Last year, in fact, Sikh voters overwhelmingly supported a united India and were key to the election of the Congress Party—the party of Indira Gandhi—to govern the Sikh homeland of Punjab. Support for Congress was especially strong in majority-Sikh districts. And Punjab’s Chief Minister is a strongly pro-unity Sikh, Amarinder Singh, who has alleged separatist influence in the Canadian government.

Harjit Sajjan, a Sikh who is Canada’s Minister of National Defence, firmly denied the claim. And on Justin Trudeau’s visit to India this year, Singh agreed to a photo-op including Sajjan. But the Chief Minister let it be known that he’d handed over a list of Canadians he suspects of fundraising for Punjab’s few remaining separatist Sikh militants.

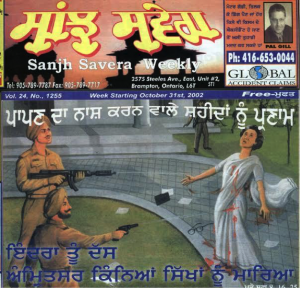

The listed suspects amount to a tiny subculture among Canada’s 450,000 Sikhs, the vast bulk of whom seek no return to the bloody 1980s and 1990s, when the battle for Khalistan took some 20,000 lives in India, most of them Sikh. But the hardliners are a well-organized political force, still raising the cry of “Khalistan Zindabad!”—long live Khalistan—in some Canadian gurdwaras where “martyred” Sikh assassins are memorialized as models for the young. These include the two bodyguards who machine-gunned Indira Gandhi. Khalistani fervour is alive on social media and a 2018 tweet from “George” (@PCPO_Brampton) declared: “Indira’s assassins are HEROES. Sikhs should glorify them.”

The endurance of such attitudes in Canada reflects the weak record of its justice system in deterring violence. For years, it seemed, Canadian courts were where terrorism cases went to die.

For the most part, it’s a record of inaction. In 1985, Ujjal Dosanjh, a Canadian Sikh moderate who publicly condemned prime minister Gandhi’s murder, was severely beaten in Vancouver by a Khalistani thug with an iron bar. No one was convicted. The same year, Balraj Deol, another vocal moderate, was beaten by a group of Sikh militants in Ontario. Again, no-one was convicted.

In 1986, Parmar and several others were charged in Canada with a plot to blow up the Indian parliament. The case failed on a technicality and Parmar walked free. Also in 1986, four separatists shot a visiting Punjab cabinet minister on Vancouver Island. The gunman, Jaspal Atwal, was sentenced to 20 years, but was released after four years and became a Liberal party activist. In 1988 and again in 1998, a British Columbia publisher, Tara Singh Hayer, was shot, the second time fatally, after publicly implicating Parmar and Bagri in the Air India bombing. No one has been charged with Hayer’s murder. Meanwhile, Talwinder Parmar fled Canada for Pakistan and was killed by police in Punjab in 1992, without facing trial for the destruction of Flight 182.

In 2005, a four-year Canadian trial of Sikhs accused of participating in Parmar’s plot ended with acquittals for two members of the Babbar Khalsa—Ajaib Singh Bagri and Ripudaman Singh Malik. Witnesses against both Malik and Bagri reported receiving death threats, for which no one was ever arrested. A third accused, Inderjit Singh Reyat, previously convicted for making the Narita airport bomb, pleaded guilty to manslaughter in return for a five-year sentence for the Kanishka bomb. He confessed that he built both bombs for Parmar, a fact confirmed by surveillance; Canadian intelligence officers had tailed both men to a test bombing, three weeks before the real thing. But Reyat refused to name any other members of the conspiracy. His claims of ignorance led to a third conviction, for perjury. He is now free and living in British Columbia.

All of this may explain the nonchalant attitude shown by Sikhs who openly revere Talwinder Parmar—despite the fact that the judge, the defence and the prosecution at the Air India trial all agreed that Parmar (long dead by then) led the plot. So did retired Supreme Court Justice John Major, who conducted a judicial inquiry and reported in 2010 that it was a “fact” that Parmar commissioned both bombs.

The Canadian nonchalance regarding Sikh extremism extended to the political class, too. A startling example came In 2007, when politicians flocked to court the crowd on Vaisakhi—the birthday of the Sikh religion—at the annual parade run by the Dasmesh Darbar gurdwara in Surrey, BC. During that year, the temple committee added Talwinder Parmar to the lineup of killers whose portraits, garlanded with tinsel, adorned the parade floats.

At the time, the oversize image of Parmar had not yet been fixed to the outside wall of the temple. The posters on floats were a test—and none of the politicians uttered a peep. MPs from all major Canadian political parties attended, as did the Liberal premier of British Columbia, Gordon Campbell—around the same time as his fellow Liberal, Ontario premier Dalton McGuinty, visited another temple exhibiting its own picture of Parmar in a heroic pose.

Questioned about his presence at the parade, Premier Campbell at first said there was no problem with what he’d seen—adding that he’d attend again in future years. A day later, though, his spokesman withdrew that statement and said the Premier was “upset” about the posters.

Conservative MP Jim Abbott, attending on behalf of then-prime minister Stephen Harper, flip-flopped in the opposite direction. First, he said he was “flabbergasted” to hear that Parmar had been honoured—but later consulted the party brass and said he would “vigorously defend” the event. Both Liberal and New Democratic Party MPs saw no reason to make a fuss. Sikh voters comprise important constituencies in several swing ridings in B.C. and Ontario, and the major parties didn’t want to risk alienating any part of them.

Two notable Liberals, though, stayed away from the parade. Both condemned the glorification of the Air India bomber; and both were Sikhs who bore the scars of their previous encounters with Parmar’s admirers. One was Dave Hayer, a member of the provincial legislature and the son of the murdered publisher, Tara Hayer, who had accused Parmar and Bagri 20 years earlier. The other no-show was the aforementioned Ujjal Dosanjh, victim of the 1985 beating, who rose to become Premier of B.C. and later a federal Liberal cabinet minister.

One indicator of the limited extent of extremist views within Canada’s Sikh community: these two vocal anti-extremists were elected and re-elected for 20 years in Dosanjh’s case and for 11 years in Hayer’s. Even so, they are routinely dismissed as spokesmen for the Sikh community by more radical Sikhs who have never sought election. Strangely, though, it is often the latter who have the ear of white politicians.

* * *

Even today, the hardliners remain a political force in Canadian politics. That became evident late last year, when Jagmeet Singh, a 39-year-old Sikh activist from Ontario, captured the leadership of Canada’s left-leaning New Democratic Party.

Singh got his start in Canadian public life by fighting for Sikh causes. Two of his earliest supporters—his brother, Gurratan, and his leadership campaign spokesman, Amneet Bali—were founders of the Sikh Activist Network, which they called “a previously underground network…of Sikh activists working for social justice while resisting the poisonous exploitative and murderous powers of neo-imperialism.” Their literature pledged to fight the “Oppressive Domination of the Fascist Indian Machinery.”

Jagmeet Singh himself had appeared at Khalistani events in North America, had been denied a visa to visit India, and had campaigned for clemency for a confessed Babbar Khalsa terrorist involved in the 1995 assassination of Punjab’s Chief Minister, Beant Singh (along with 17 bystanders). Singh later took part in a successful drive to have the Ontario legislature declare the 1984 massacre of Sikhs in India a “genocide.” Now, as a federal party leader, he hopes to achieve the same in the national parliament.

The day after he won the NDP leadership in 2017, Singh’s long involvement with these issues led me to explore the topic on a CBC television news show that I hosted. In an on-air interview for Power and Politics, I asked Singh whether he thought it appropriate for some Sikhs to put up martyr posters glorifying Talwinder Parmar, despite his status as Canada’s worst mass murderer.

Singh declined five invitations to answer that question. He would not condemn the posters and would only say that he condemned the bombing—but without conceding that Parmar or any Sikh was to blame for it.

“I don’t know who’s responsible,” Singh said, “but I think we need to find out who’s responsible, we need to make sure that the investigation results in a conviction of someone who is actually responsible.”

This answer raised serious concerns—including among some NDP supporters—because what Singh said wasn’t accurate: Canada did secure a conviction—three convictions, in fact—of “someone who is actually responsible” for the Air India bombing. Parmar’s bomb-maker, Inderjit Reyat, was convicted first for the explosion at Narita airport, then for the one aboard Flight 182, and finally for perjury. Reyat also confirmed that Parmar ordered both bombs. Yet five months passed until Jagmeet Singh revised his answer to my question. He now acknowledges Parmar’s guilt and condemns the posters honouring him.

Singh’s comments in his CBC interview also were unsettling for his repetition of extremist tropes. The call to “find out who really did” Flight 182 often comes from Parmar’s admirers, who entertain the conspiracy theory that the Indian government blew up its own plane, using Parmar as its agent to discredit the Khalistani cause. Such theories are promoted by self-appointed voices in the Sikh community, such as the World Sikh Organization, launched at the infamous 1984 Madison Square Garden convention. The WSO complained in 2008 that John Major’s judicial inquiry failed to take the so-called Air India Truthers seriously.

On Twitter, Jagmeet Singh’s defenders denounced my interview with him in a blizzard of angry tweets. Some declared flatly that the Indians were behind the bombing. Others condemned the CBC and me for asking about the Parmar posters “just because Singh is Sikh.” Jaskaran Sandhu, a WSO board member called me “racist” and “bigoted.” It was as though only a bigot would object to the glorification of a mass killer of Indo-Canadians, including many Sikhs.

A second wave of critics claimed that I’d failed to grasp the “cultural” reasons for the veneration of Parmar, arguing that he was a victim of “persecution” whose “confession to the Air India bombing came under torture” by the Indian police. In fact, the official findings of Parmar’s guilt rest on hard evidence acquired while he was in Canada, seven years earlier. Neither the trial nor the inquiry relied upon any rumoured confession.

For his part, Jagmeet Singh seemed to agree that my questions smacked of racism. A week after the interview, asked directly if that was so, he replied, “Should I just say, yes?” He went on: “I think there was definitely some sort of clear problematic line of thought behind that question, so I’m definitely concerned with it … It was offensive to me that that was even a question.”

It was clear, though, that the question Singh found “offensive” was not one he’d been asked: whether he condemned the bombing. “It’s obvious that anyone would denounce something as heinous and as tragic as that incident,” he said. “The fact that that question is being raised makes me wonder why it is being raised.”

In truth, he’d been asked about the martyr posters, not the bombing. Asked if the posters should come down, he ducked that question, too.

“I’m not here to tell what a community should or shouldn’t do.”

As the controversy unfolded, Singh’s supporters continued to paint him as a victim of racism. A Toronto podcaster and self-described media critic, Jesse Brown, declared that my questions to Singh were “irresponsible, and “looked racist.” More inventively, British blogger Sunny Hundal argued that Parmar’s sympathizers didn’t honour Parmar because he was a terrorist, but because he led the Babbar Khalsa (which was, in fact, the terrorist organization which blew up Air India). For his part, the WSO’s President, Mukhbir Singh, contended that Sikhs who display Parmar’s portrait—for the most part grizzled veterans of the separatist struggle—were “naïve, not radical,” because, for some unexplained reason, they “think” that Parmar was innocent.

Anyone familiar with the politics surrounding militancy in, say, the Muslim community, might expect that Singh’s political rivals would have seized upon his remarks; the charge that left-wingers are “soft on terror” is commonplace in many countries. Yet Canada’s ruling Liberals and the opposition Conservatives both steered clear. The NDP have no monopoly on cynical ethnopolitics; and the other parties were no more eager to alienate any part of the Sikh community.

This background is well understood in India, where Justin Trudeau—like his Conservative predecessor, Stephen Harper—was taken to task for Canada’s tolerant attitude towards Khalistani extremism. On Trudeau’s arrival for his trade mission in February, the Chief Minister of Punjab, Amarinder Singh, was quoted as saying, “there seems to be evidence that there are Khalistani sympathizers in Trudeau’s cabinet.” Indeed, he once called Sajjan, Canada’s Defence Minister, a “Khalistani sympathizer.”

Although there’s no evidence that Sajjan has done anything to promote Sikh separatism, he has long been viewed with suspicion by Sikh moderates. In December, 2014, his nomination to stand for the Liberal party provoked an angry on-camera walkout by some 30 of his fellow Sikh Liberals. The scene played out in the district of Vancouver South—once held by the moderate Ujjal Dosanjh.

To outsiders, Sajjan seemed like an attractive candidate—a decorated Afghan war veteran and a former city cop. But the party rebellion included senior figures from the Sikh mainstream who’d been Liberal stalwarts for years. They complained that their preferred candidate, a secular moderate named Barj Dhahan, had been pushed aside by the party brass in favour of Sajjan, a turbaned Sikh whose father is a veteran WSO supporter and whose nomination was backed by Liberal power-broker Prem Singh Vinning, an ex-president of the WSO.

Jagdeep Sanghera, twice chairman of the Liberal executive in Vancouver South, joined the revolt. “The majority of the Sikhs are not part of the WSO. As a group we have decided we will not support the Liberal team,” he said. Kashmir Dhaliwal, former head of the Khalsa Diwan, Canada’s oldest Sikh society, added that “the Liberal Party, especially Justin, is in bed with extremist and fundamental groups. That’s why I decided to leave the Liberal Party.” Another to quit was Majar Sidhu, who lost three family members in the Air India bombing. Referring to the Conservative prime minister of the day, Stephen Harper, Sidhu said, “the Liberal Party is encouraging terrorist people. I’m supporting Harper.”

Still, there was no retreat by Trudeau. Although the Vancouver South rebels were nearly all Sikhs, Trudeau’s top aide, Gerald Butts, scoffed at the affair, telling me that, “I suppose you’re going to do a story about how the Sikhs are taking over the Liberal Party.”

It was a familiar tactic used by Khalistanis and their political allies: cast any criticism of Sikh radicalism as if it were a racist attack on all Sikhs. The remark also suggested that Butts identified “the Sikhs” with the WSO; and that Sikhs who don’t stand with the WSO are not really Sikhs.

* * *

Despite such controversies, Trudeau had every reason to expect that the final leg of his trip to India would go well. Heading into a pivotal meeting in New Delhi with prime minister Narendra Modi, Trudeau strongly endorsed a united India. Then, pressed to repudiate the posters back home honouring Talwinder Parmar, the Prime Minister said what NDP leader Jagmeet Singh did not: “I do not think we should ever be glorifying mass-murderers, and I’m happy to condemn that.” So far, so good. But all of that would be forgotten amid the furore that unfolded next.

It began with a buzz on my phone, signaling a new arrival in my inbox. Astonishingly, it was a snapshot from Mumbai, showing Trudeau’s wife, Sophie, in an evening gown, posing with a convicted Khalistani hit-man.

I gaped at the screen. I knew this guy. In fact, I’d interviewed him some years back about a campaign finance scandal. It was the same Jaspal Atwal whom Ujjal Dosanjh had accused of trying to beat his head in with an iron bar; and the same Jaspal Atwal who, as described earlier, had been convicted for the attempted murder of a Punjab cabinet minister on Vancouver Island in 1986.

More pictures came in, showing Atwal with members of Trudeau’s delegation. Another showed a posh-looking invitation to the next day’s dinner for the Trudeaus in New Delhi. The host: Canada’s High Commissioner in New Delhi. The guest: Jaspal Atwal. A convicted terrorist had the inside track on Trudeau’s Indian junket.

The story came together quickly, and the prime minister’s office rushed to contain the damage by rescinding Atwal’s invitation to the New Delhi bash. Then they blamed a Sikh Liberal MP from B.C., Randeep Sarai, for putting Atwal on the guest list. Sarai apologized, stepped down from his post as chair of the Liberals’ Pacific Caucus, and pledged that, “moving forward, I will be exercising better judgment.”

But it was too late to contain the scandal. I was marched from one studio to another to discuss the story again and again. I also interviewed Dosanjh, the former Liberal cabinet minister and well-known Sikh moderate, who observed acidly that the prime minister had long been “cavorting with Khalistanis.”

The Indian media pounced, too. The Sophie-and-the-hitman photo went viral. According to one estimate, the story in its various forms got 300-million hits in India.

As bad as this was for Trudeau, his team nevertheless found a way to make it still worse—by trotting out a dubious theory that unnamed “rogue elements” within the Indian government had somehow conspired to manufacture the Atwal affair in order to sabotage the trip.

This Indian Plot theory did not sell well—certainly not with the Modi government, which called it “baseless and unacceptable.” The theory raised eyebrows in Canada, too, for it seemed to suggest that Canada’s High Commissioner to India was an Indian agent. It also contradicted the earlier claims of Trudeau’s staff that the whole episode had been the fault of their own MP, Randeep Sarai.

And then things got even worse. It soon emerged that Atwal had been a fixture at Liberal events and fundraisers, both federal and provincial, for years. This would-be murderer had even served on the Liberal executive for a federal electoral district and had set off an earlier furor by getting himself invited to the British Columbia legislature.

Eager to paint the Liberal government as soft on terror, the opposition Conservatives promised to force a Parliamentary vote on a motion to condemn “terrorism, including Khalistani extremism and the glorification of any individual who has committed acts of violence.” But that plan sputtered when the WSO and its allies bombarded the Conservatives with angry messages swearing never to vote Conservative if the motion were not abandoned. “This sort of political rhetoric will damage the reputation of Canadian Sikhs in the public eye and hurt the community immensely, particularly our youth,” the WSO tweeted. The next day, the Conservatives caved. The motion was abandoned.

Soon, though, the spotlight turned back to NDP leader Jagmeet Singh. In early 2018, videos emerged of the NDP leader attending Sikh separatist events in California and London. The videos were several years old but raised new questions that Singh had difficulty answering. Pressed on whether he endorsed armed struggle in the cause of Khalistan, he replied, “Well, I think you’re actually on the complexity of the situation…Given that it’s complex, it requires that thoughtfulness to proceed forward.”

* * *

None of this changed the fact that Khalistani militants remain a small minority of Canadian Sikhs, whose political influence frustrates moderate Sikhs in both Canada and India. Meanwhile, Khalistanis still hope for a referendum on independence in 2020—although their chances are slim: Sikhs in Punjab keep voting in large majorities for a united India.

But the separatists’ political impact in Canada is keenly felt by relatives of the Flight 182 victims. Perviz Madon described the problem when she testified at the Air India inquiry in 2006. Her husband, Sam, had gone down with Flight 182, leaving her with two young children to raise alone. She urged Justice Major to look squarely at the Khalistani parades, the so-called martyrs, and the pandering politicians who turn a blind eye.

“We need to stop our politicians from attending those kind of events,” she said. “I’m sorry, I know it’s about your votes. But that’s dirty business. You don’t want to be associated with a group that is linked to terrorism. You don’t want those kinds of votes.”

So far, though, they do. Three decades after Talwinder Parmar slaughtered 329 innocents on Flight 182, Canada’s politicians still remain wary of standing up to those who call the man a hero.