Politics

The Need for a Culture of Achievement

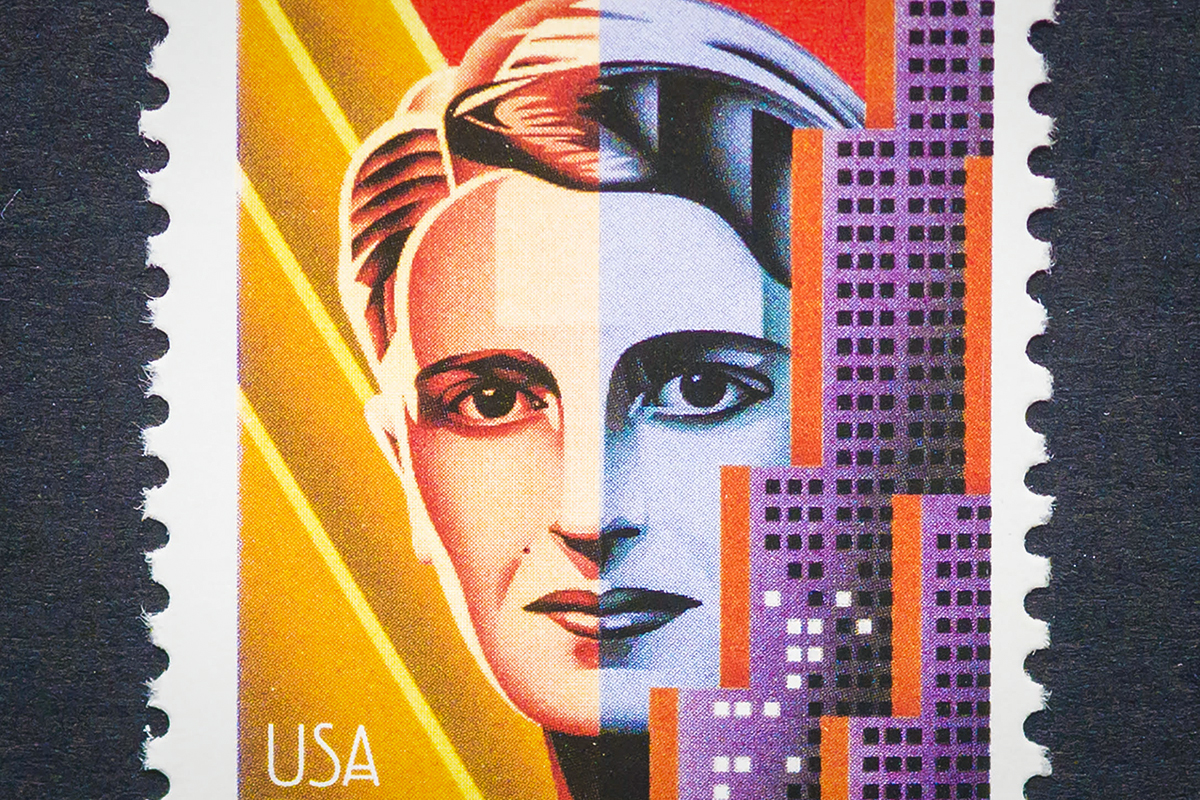

Rand’s style often caused her to be misunderstood and dismissed as some kind of Nietzschean.

What does Ayn Rand have to offer to our era? The Russian-born American author rose to prominence as a novelist and philosopher in the middle of the 20th century, and attracted a large audience on the American Right with her sharp critique of communism. The comprehensive alternative she presented in her philosophy and her fiction championed individualism against collectivism—the fundamental ideological conflict of her era. That is why, despite her atheism, she enjoyed significant influence on the American Right and is still considered indispensable, even by many who had profound disagreements with her.

The issues of today are not quite the same, nor are the ideological alignments. Yet people are still seeking out Ayn Rand’s ideas and trying to understand her influence, if sometimes with less than edifying results. A recent piece in Quillette attributes her influence and relevance primarily to her pop culture celebrity and the magnetism of her dark and famously penetrating eyes. But there is much more to Rand’s enduring relevance, and to understand it, we have to delve into the substance of her ideas.

Ayn Rand’s influence was closely tied to her engagement with the big events of her era. She presented her ideas, to an extent unusual for a philosopher, embedded in commentary on the political and cultural news of the day. She offered new thoughts on epistemology and concept-formation in an article on the Republican National Convention of 1964. Her ideas on the relationship between reason and emotion were presented in a speech on the contrast between the two big cultural events of 1969: Woodstock and the Moon landing.

But because she was operating on a deeper philosophical level, her message transcends the particular context in which she wrote. In her introduction to the 25th anniversary edition of The Fountainhead, she quoted Victor Hugo: “If a writer wrote merely for his time, I would have to break my pen and throw it away.”

Her philosophy is particularly relevant to our current iteration of the culture war. I say the current iteration, because the roots of our culture war stretch back longer than we may think. There is little you can say about the ideological conformity of the social media era that she didn’t expose in The Fountainhead—a dissection of the ideological conformity of Modernist intellectuals during the Red Decade of the 1930s.

The theme of The Fountainhead, Rand later wrote, was “individualism versus collectivism, not in politics, but in man's soul.” Collectivism in the soul is embodied in the character of Peter Keating, the ultimate conformist whose only goal in life is to “read the room,” signal his virtue, and be what others expect him to be. But this creed is given its self-conscious voice by the novel’s main villain, Ellsworth Toohey. He is an essential character for understanding her era, and our own: the totalitarian intellectual.

In a way, characters like Toohey are an answer to the Jeffersonian assumption that the spreading light of knowledge and education would guarantee the triumph of liberty. By the early 20th century, tyranny was no longer championed by monarchs and their hangers-on; it had become a creed of the intellectuals. This is a conundrum with which the best authors of the time grappled. (See, for example, the character of O’Brien in Nineteen Eighty-Four.)

Rand uses Toohey to show how the psychology of conformity was given voice, justification, and encouragement by the collectivist philosophy of the era. Toohey helps her capture the funhouse-mirror quality of this ideological conformity, its essential emptiness and barrenness. In a moment of confession, here is how he describes the ideal world of the collectivist:

A world where the thought of each man will not be his own, but an attempt to guess the thought of the next neighbor who’ll have no thought—and so on, Peter, around the globe. Since all must agree with all. A world where no man will hold a desire for himself, but will direct all his efforts to satisfy the desires of his neighbor who’ll have no desires except to satisfy the desires of the next neighbor, who’ll have no desires—around the globe, Peter. Since all must serve all. A world in which man will not work for so innocent an incentive as money, but for that headless monster—prestige. The approval of his fellows—their good opinion—the opinion of men who’ll be allowed to hold no opinion. An octopus, all tentacles and no brain.

That sounds like an ordinary Tuesday in the hive-mind of Twitter. Toohey even grasps what is known today as “audience capture”: “I’ll have no purpose save to keep you contented. To lie, to flatter you, to praise you, to inflate your vanity.” In his collectivist future, the leader is the biggest follower of all.

This is all in contrast to the novel’s real purpose, which is to show us the totally independent man, someone with no collectivism in his soul: her protagonist, the young architect, Howard Roark. Explaining why he refuses payment and credit on one particular project, Roark says: “The only thing that matters, my goal, my reward, my beginning, my end is the work itself. My work done my way.”

Of central importance to The Fountainhead is the distinction between the “first-hander” and the “second-hander”—respectively, the person who acquires ideas and values first-hand through contact with reality and the person who deals with the world at one remove, adopting the opinions and tastes of others. Long before Instagram, Roark describes the latter as the sort of person who “can’t say about a single thing: ‘This is what I wanted because I wanted it, not because it made my neighbors gape at me.’”

Rand’s goal was to show us what it’s like to see the world purely through one’s own eyes.

Ayn Rand is known for her politics, but as she wrote, “I am not primarily an advocate of capitalism, but of egoism; and I am not primarily an advocate of egoism, but of reason.” The deepest theme in her work is the need to see the world first-hand and to follow unfettered reason wherever it leads in pursuit of the truth. “Freedom,” she wrote, “is the fundamental requirement of man’s mind.”

The basic need of the creator is independence. The reasoning mind cannot work under any form of compulsion. It cannot be curbed, sacrificed, or subordinated to any consideration whatsoever. It demands total independence in function and in motive.

The dominant contemporary “progressive” doctrines, by contrast, are second-handedness turned into a system. “Critical theory,” for instance, denies on principle our ability to see the world first-hand, to see things as they really are, and instead insists that everything is filtered through “social constructs.” We all have no choice, in this outlook, but to be Peter Keating—leaving us vulnerable to manipulation by the latest Ellsworth Toohey. The current variation on this outlook may be relatively new, but it has deep philosophical roots to which Rand provided detailed philosophical answers, including in technical works of philosophy defending our ability to know reality first-hand in the deepest sense.

But she had greater influence as a champion of thinking as an ethos. This line from Atlas Shrugged, in particular, speaks to our age: “There are no evil thoughts except one: the refusal to think.” This was not a mere rhetorical flourish. She really did regard the refusal to think, not just as evil, but as the essence of evil. In her morality, the most basic choice is the choice to think:

In any hour and issue of your life, you are free to think or to evade that effort. But you are not free to escape from your nature, from the fact that reason is your means of survival—so that for you, who are a human being, the question “to be or not to be” is the question “to think or not to think.”

Elsewhere, she wrote:

Nothing is given to man on earth except a potential and the material on which to actualize it. The potential is a superlative machine: his consciousness; but it is a machine without a spark plug, a machine of which his own will has to be the spark plug, the self-starter and the driver; he has to discover how to use it and he has to keep it in constant action. The material is the whole of the universe, with no limits set to the knowledge he can acquire and to the enjoyment of life he can achieve. But everything he needs or desires has to be learned, discovered and produced by him—by his own choice, by his own effort, by his own mind

To be “in focus” is the highest term of praise in Rand’s philosophy, and the worst thing one can be is “out of focus.” “Focus” here refers to “a full, active, purposefully directed awareness of reality”—to thinking as a moral choice. It is her answer to one of the oldest conundrums in philosophy: How can one knowingly do evil? Her answer is that to be evil is to be deliberately out of focus. One does evil because one does not know what one is doing—but the lack of knowledge is not mere ignorance. It is the choice not to know, to push knowledge out, to refuse to examine the meaning and implications of your actions.

The doctrines now widely derided as “wokeness” constitute a system for this kind of evasion. It offers a program of self-censorship that consists of closing oneself off from the expression of any ideas that might be labeled as wrong. Potentially offensive tweets, books, comedy specials, statues—they all have to go, purged in a ritual of purification. Paralyzed by the fear of evil thoughts, adherents embrace the refusal to think.

But notice that the fully independent man’s individualism is expressed, not just in his thoughts, but in his work. In The Fountainhead, Howard Roark explains the “meaning of life”:

Roark got up, reached out, tore a thick branch off a tree, held it in both hands, one fist closed at each end; then, his wrists and knuckles tensed against the resistance, he bent the branch slowly into an arc. “Now I can make what I want of it: a bow, a spear, a cane, a railing. That’s the meaning of life.”

“Your strength?”

“Your work.” He tossed the branch aside. “The material the earth offers you and what you make of it.”

This theme is developed most fully in Atlas Shrugged. The settings for Rand’s novels tended to follow her own experiences, but at a delay of a few years. Her first novel, We the Living, was about independent-minded students struggling to survive in the early years of the Soviet dictatorship—just as she had been doing a few years earlier. In The Fountainhead, her heroes were mostly artists and intellectuals at the beginning of their careers, struggling to break through with their creative visions. In Atlas Shrugged, written after she had become a bestselling author who mixed with business magnates, her heroes are businessmen who are also pursuing their creative visions, but this time in the form of building rail lines and inventing new metal alloys.

Rand’s moral philosophy is best-known for her defense of self-interest. But its real heart is her defense of the central virtue that gives meaning to the self: productiveness, the embrace of work and the spirit of work. Behind that is a rational, secular ethics in which morality is based on the requirements of human life, of which the central requirement is productive work. It is, she wrote, the recognition “that your work is the process of achieving your values, and to lose your ambition for values is to lose your ambition to live—that your body is a machine, but your mind is its driver, and you must drive as far as your mind will take you, with achievement as the goal of your road.”

A few years back, sociologists Bradley Campbell and Jason Manning published an influential study in which they described three kinds of cultures, each defined by what lends people status and gives their lives meaning and value. A culture of honor is epitomized by the practice of dueling, using violence to answer a perceived insult. In a culture of dignity—think of Frederick Douglass or Martin Luther King, Jr.—one’s sense of value is primarily internal and one can patiently bear injustice without diminishing it. Campbell and Manning call our current culture one of victimhood, in which the source of status and meaning is one’s claim to oppression, suffering, and “marginalization.” Hence the obsessive ferreting out of “microaggressions,” no matter how trivial.

This describes the activist Left, but it also increasingly describes resentful American conservatives, who have adopted their own obsession with victimhood and martyrdom—an insecure fixation on the fear that somehow, somewhere the “elites” are looking down on them.

Rand’s answer lies in her advocacy of productive work. In place of a culture of honor, or dignity, or victimhood, she offered a culture of achievement, in which work, innovation, and productiveness give life its meaning and value.

In my own book on Atlas Shrugged, I likened Ayn Rand’s approach to the Ancient Greek legend of the contest between Homer and Hesiod, the two greatest poets of the early Classical world. Legend has it that they met and tested their verses against one other in a kind of ancient poetry slam. Homer ran rings around Hesiod, but the judge gave the award to Hesiod anyway, because “he who called upon men to follow peace and husbandry should have the prize rather than one who dwelt on war and slaughter.” This sums up a basic problem that has resonated down the millennia. In more modern times, defenders of the Enlightenment have lamented that the sturm und drang of the irrational Romantics and their dangerous obsessions with blood and soil, were usually presented in a more dramatic and stirring form than the Enlightenment’s ideals of peace and scientific discovery.

Ayn Rand set out to correct this defect, lending all the color and drama of literary Romanticism to the Enlightenment values embodied by heroes who are architects, inventors, and philosophers. She wrote the kind of novel in which two of the main characters bond over their heroic effort to stem a break-out at a steel furnace:

In the few moments which Rearden needed to grasp the sight and nature of the disaster, he saw a man’s figure rising suddenly at the foot of the furnace, a figure outlined by the red glare almost as if it stood in the path of the torrent, he saw the swing of a white shirt-sleeved arm that rose and flung a black object into the source of the spurting metal. It was Francisco d’Anconia, and his action belonged to an art which Rearden had not believed any man to be trained to perform any longer.

Years before, Rearden had worked in an obscure steel plant in Minnesota, where it had been his job, after a blast furnace was tapped, to close the hole by hand—by throwing bullets of fire clay to dam the flow of the metal. It was a dangerous job that had taken many lives; it had been abolished years earlier by the invention of the hydraulic gun; but there had been struggling, failing mills which, on their way down, had attempted to use the outworn equipment and methods of a distant past. Rearden had done the job; but in the years since, he had met no other man able to do it. In the midst of shooting jets of live steam, in the face of a crumbling blast furnace, he was now seeing the tall, slim figure of the playboy performing the task with the skill of an expert.

Rand’s style often caused her to be misunderstood and dismissed as some kind of Nietzschean. But her goal was to give the air of self-assertiveness and the dramatic intensity of the Romantics back to the Enlightenment values of science, reason, and productiveness. Critics may complain that she wrote for “adolescents,” but her appeal to intelligent and ambitious young people is obvious: She understood that they require a vision of a life of work as something more than drudgery, accepted either as a duty or as an imposition.

She also understood that the young, when inflamed with a passion for work and achievement, would devote themselves to things more useful and edifying—and more personally fulfilling—than the hectoring didacticism of the activist Left or reactive trollishness of much of today’s Right.

The best outcome of the culture war is that culture wins: Instead of trying to cancel other people’s projects, we should respond with exciting creations of our own, highlighting what our philosophy and worldview have to offer. As an answer to contemporary grievance-mongering and self-pity, Ayn Rand’s vision of a culture of achievement is worth taking seriously.