Politics

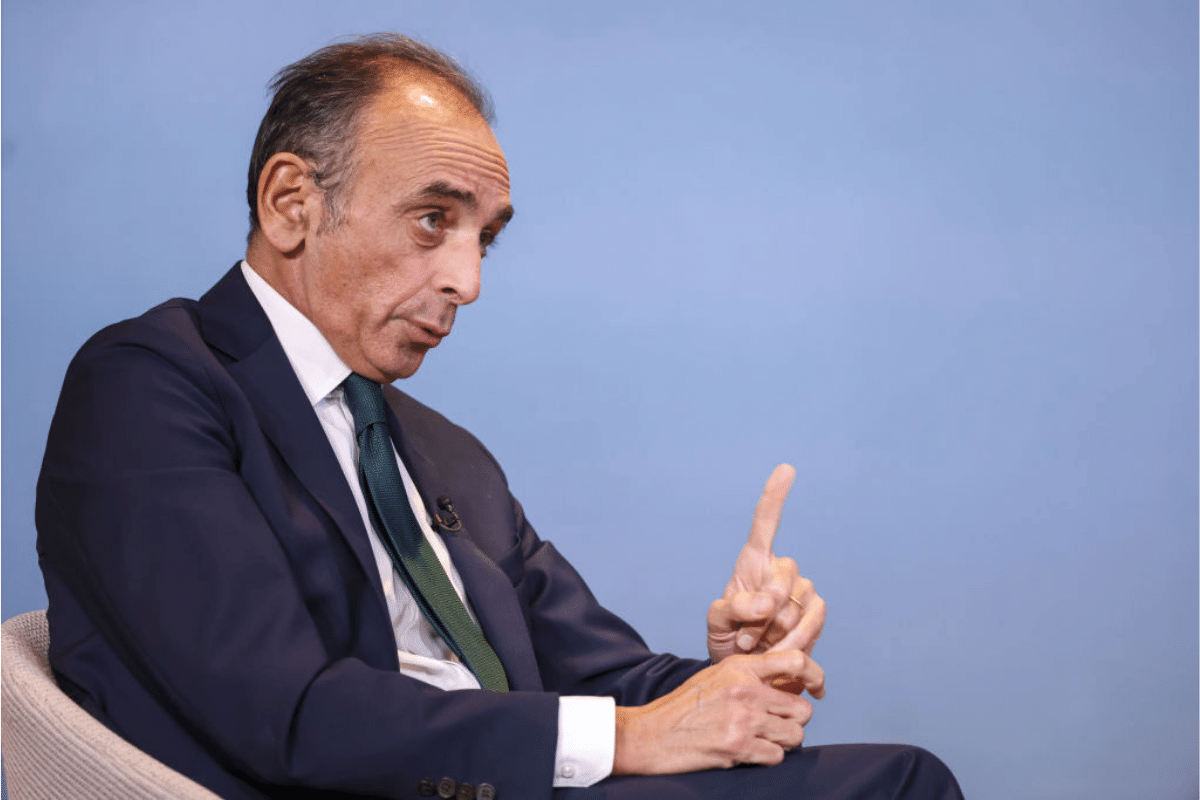

Zemmour’s Final Word

The danger—or opportunity, depending on your view—is that two radical candidates like Mélenchon and Zemmour win the first round.

This year, May 5th marked the 200th anniversary of the death of Napoleon, France’s most famous historical figure and the greatest military leader of the 19th century. The response to the event was as sad as it was predictable. Bonaparte, much of the country’s Left cried, was a white supremacist who re-established slavery—a line which President Emmanuel Macron repeated in his speech to mark the occasion. What should have been a moment of pride and national unity instead provided a reminder of the fault lines in French and Western culture more broadly.

A few hours after Macron’s remarks, a conservative political commentator named Éric Zemmour appeared on what was, until recently, his nightly post on Face à l’Info, the most popular political talk show in the crowded French primetime market. Zemmour’s time as the show’s star had been turbulent. In two short years he increased the ratings to up to a million viewers per night, received a conviction for hate speech and had it overturned, and was finally banned from further appearances based on his presumed—but as yet unconfirmed—political aspirations (the airtime permitted for political candidates is strictly regulated in France).

Since his ouster from CNews, Zemmour has not fallen silent. He recently published a book entitled La France N’a Pas Dit Son Dernier Mot (“France Has Not Said Its Last Word”), appeared on stages all over the country, and given too many television, radio, and podcast interviews to count. This has all been done on the pretext of promoting his book. But few—including the French telecommunications authority who took him off the air—doubt that Zemmour has his eyes on the presidential election in six months’ time.

Recent polls have tipped Zemmour to beat Marine Le Pen in the race for the Elysée. Somehow he has become a political sensation without even formally declaring himself a candidate. Above all, Zemmour is a lightning rod because he skilfully and unapologetically attacks everything the cosmopolitan class stand for—internationalism, environmentalism, multiculturalism, and a thinly veiled contempt for their nation’s history. In response to Macron’s weasel words about Napoleon, Zemmour described Bonaparte’s conquests as the “apotheosis” of a thousand years of French history.

Born in the working class suburb of Montreuil, now part of the notorious Saint-Denis department on the northern outskirts of Paris (where police found and killed the lead attacker of the November 2015 attacks), Zemmour’s parents were Berber Jews who fled Africa during the Algerian war. His formative years were spent in the Château Rouge section of Paris’s 18th arrondissement, an auspicious and seemingly symbolic location for his upbringing. At the time a poor but cohesive Jewish neighbourhood, today Château Rouge is the focal point of a crack epidemic, and is one of the most crime-ridden and—to Zemmour’s generation—unrecognisable parts of the capital.

An ambitious and by many accounts awkward young man, Zemmour studied at the prestigious Institut d’Études Politiques (“Sciences Po”) in Paris, but twice failed to gain admission to the École Nationale d’Administration (ENA) where Jacques Chirac, François Hollande, and Emmanuel Macron got their start in the political milieu. Devastated by his first big failure, Zemmour briefly worked in advertising before joining Le Quotidien de Paris as a political journalist, eventually being hired by Le Figaro, France's conservative paper of record.

Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, in addition to his journalistic duties, Zemmour wrote a series of undistinguished biographies and novels, finally coming to public attention in 2006 with the release of a book entitled Le Premier Sexe, in which he criticised the feminisation of society. While this polemic scored him television and radio interviews, its success was dwarfed by that of his 2014 work Le Suicide Français, which sold 500,000 copies in France and made Zemmour a name internationally. Perhaps due to his success, Zemmour has spent much of his time over the last few years living under permanent police protection. Earlier this year, he was filmed by an assailant who threatened him as he walked down the street with shopping bags.

Tout mon soutien à Éric #Zemmour agressé en pleine rue par une racaille qui l’a insulté et lui a craché dessus alors qu’il faisait ses courses.

— Eric Ciotti (@ECiotti) May 1, 2020

Il n’y aura naturellement pas de suite. Imaginons la situation inverse.... pic.twitter.com/y5mNZk6InX

In Le Suicide, two strands of Zemmour’s thought were elucidated. The first is déclinisme, the idea that France is in a state of inexorable decline. The second is the grand remplacement theory, which holds that black Africans and Arab Muslims are systematically invading and colonising France. Hitherto regarded as “extreme,” recent studies suggest that a solid majority of the French population accepts both theories. Seventy-eight percent of respondents to a 2020 IPSOS poll said they believed France to be in a state of decline. Last month, 67 percent of respondents to a Harris Interactive poll were worried that the indigenous French population was “threatened with extinction” by black African and Maghrebian migrants.

Perhaps such statistics—which Zemmour frequently cites in speeches and media appearances—along with the success of his 2014 book, spurred him to enter politics. There is also the fact that, with her party rebrand and softening stance on various issues, Marine Le Pen has come to more closely resemble Emmanuel Macron who, with his discourse about the Islamisation of French society, has come to more closely resemble Marine Le Pen. There is also the sense that Le Pen, as the successor to a political dynasty, has dominated the populist wing of conservative politics for too long, and that it might be time for some new blood.

But the most potent factor of all is Zemmour’s own belief that the great figures of French history have all been men of letters like himself. Jean-Jacques Rousseau was a hack writer who finally made a name for himself as the revolutionary mob’s philosopher-in-chief. Rousseau greatly influenced Napoleon, an obsessive reader, who in turn was Charles de Gaulle’s hero. In Le Suicide Français, Zemmour writes: “In all Alexander’s victories there is Aristotle, according to de Gaulle. In all of Premier Consul Bonaparte’s decisions we find the echo of his youthful readings of Voltaire and Rousseau.” Zemmour, in contrast to Marine Le Pen with her narrowly political talking points, views himself as the next in a long line of literary men destined to lead France out of the doldrums towards the glories of the past.

What, then, would a Zemmour presidency look like? At home, Zemmour has said he would ban giving children non-French first names, deport illegal immigrants, stop most of the country’s legal immigration, and close approximately 540 mosques operated by Salafists and Muslim Brotherhood members. Economically, he has spoken in favour of lowering taxes to make France more competitive but has said little else, sticking to the more headline-grabbing issues of immigration and law-and-order.

His foreign policy is more concerning. Zemmour viewed the recent affaire Australiennne concerning the ruptured submarine-building contracts as the latest example of centuries-old Anglo-Saxon perfidy and aggression towards the French. Zemmour refers to the English as France’s “enemy of a thousand years” and America as “the most dangerous country in the world.” Perhaps Zemmour proves Voltaire’s point that to be a good patriot means hating the rest of the world.

On this and other issues, Zemmour has much in common with left-wing firebrand Jean-Luc Mélenchon, who was also born in North Africa to a family of modest means and moved to France in his early childhood. Mélenchon and Zemmour have both denied the Vichy regime’s responsibility for the death of 75,000 Jews sent to Nazi camps during this period. In a recent televised debate between the two, both agreed that NATO is an obsolete instrument of American imperialism. Zemmour added that he favours renouncing France’s alliances with the US, UK, and Germany and “joining hands with Russia.” It was the Russians, says Zemmour, not the British nor the Americans, who saved France during the Second World War, after which the Americans covertly colonised Europe through the common market framework which Germany now dominates.

Curiously, however, and contrary to his previously stated position, Zemmour does not favour France following Britain out of the EU. “I don’t want to divide the electorate on the European question,” he said in a recent debate against philosopher Michel Onfray, perhaps with an eye on Le Pen’s pro-Frexit stance during her abortive 2017 presidential bid. This marks the first time that Zemmour has transparently opted for politics over principle, a decision which may prove costly, given frankness has been the key ingredient in his success.

In any case, it is unclear if Frexit is as unpopular as Zemmour thinks. In 2005, when a referendum asked the French to decide whether they would ratify a “European constitution,” 55 percent voted no, a result duly ignored by French lawmakers, who ratified the Lisbon Treaty three years later regardless. This 55 percent—made up of blue collar and affluent conservatives—is surely Zemmour’s target audience if he is to have electoral success. Indeed, his appeal to bourgeois and often Eurosceptic Les Républicains voters is his main advantage over Marine Le Pen, whose base is more narrowly working-class nationalists.

Les Républicains could themselves re-emerge as serious contenders in 2022, so long as they can avoid the scandals that dogged their candidate François Fillon in 2017. Fillon nevertheless placed third in the first round with 20 percent of the vote. Xavier Bertrand, a minister under Jacques Chirac, Valérie Pécresse, an ENA graduate and current President of Île de France, France’s most populous region, and Michel Barnier are all potential LR candidates.

Barnier is particularly intriguing. Better known in the UK than in France as the intransigent technocrat who led the Brexit negotiations for the EU, Barnier has turned into something of a nativist himself. He has proposed a total moratorium on immigration, and a corresponding referendum to amend the French constitution to avoid Brussels’s condemnation for doing so. Tall and urbane, with solid experience in international affairs, Barnier might have been the man to lead France in more sober times. But today there is a sense that France is on her knees, and that only radical action can get her back on her feet.

Even if Zemmour manages to vanquish his rivals on the Right, he would still have to beat the incumbent. Historically, this has not proved difficult, and Macron’s tenure has been rocked by crippling transport and student strikes, gilets jaunes unrest, and a clumsy response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, it would take a significant change in circumstances for Zemmour to defeat Macron in the second round, given the vitriol he inspires in much of the French population.

The danger—or opportunity, depending on your view—is that two radical candidates like Mélenchon and Zemmour win the first round. In 2017, Emmanuel Macron won 24 percent of the first round vote, Le Pen 21.3, and Mélenchon 19.6. Given everything that has happened since, it is entirely possible that two extreme candidates, each with a small but devoted following, advance to the second round. It is difficult to overstate the political explosion this would cause.

Zemmour has tapped legitimate grievances among the French public. However, his depth of learning and rhetorical skills notwithstanding, I am doubtful that he is the man to improve things. France needs to change. But it does not need an unscrupulous zealot like Éric Zemmour, given to stoking resentment and manipulating history. He is an often insightful political commentator, and adroit at identifying problems, but he is ill-equipped to solve them, and might make things a good deal worse.

Zemmour calls to mind two very different English political figures. The first is Benjamin Disraeli, the Jewish boy whose inferiority complex and rhetorical genius propelled him to greatness. The second is Enoch Powell, whose speeches on immigration struck fear, contempt, and righteous indignation into the hearts of many of his countrymen. Powell became just a minor footnote in 20th century history, and I suspect that Zemmour will share his fate. But the last year-and-a-half has taught us that things can change fast. And if they change fast enough, Zemmour might, for better or worse—like his hero Napoleon—alter the course of French and European history.