Art and Culture

How D.B. Cooper and the Golden Age of Air Piracy Changed Aviation Fiction

Frank Sinatra's “Come Fly With Me” was the best-selling album in the United States for five weeks in 1958, but the irony of its popularity (or, perhaps, the source of its aspirational appeal) is that practically none of us could take up the offer to "glide, starry-eyed" on an aircraft with anybody in those days. More than 80 percent of the country had never once been on an airplane.

~Derek Thompson, the Atlantic, February 28th, 2013

I.

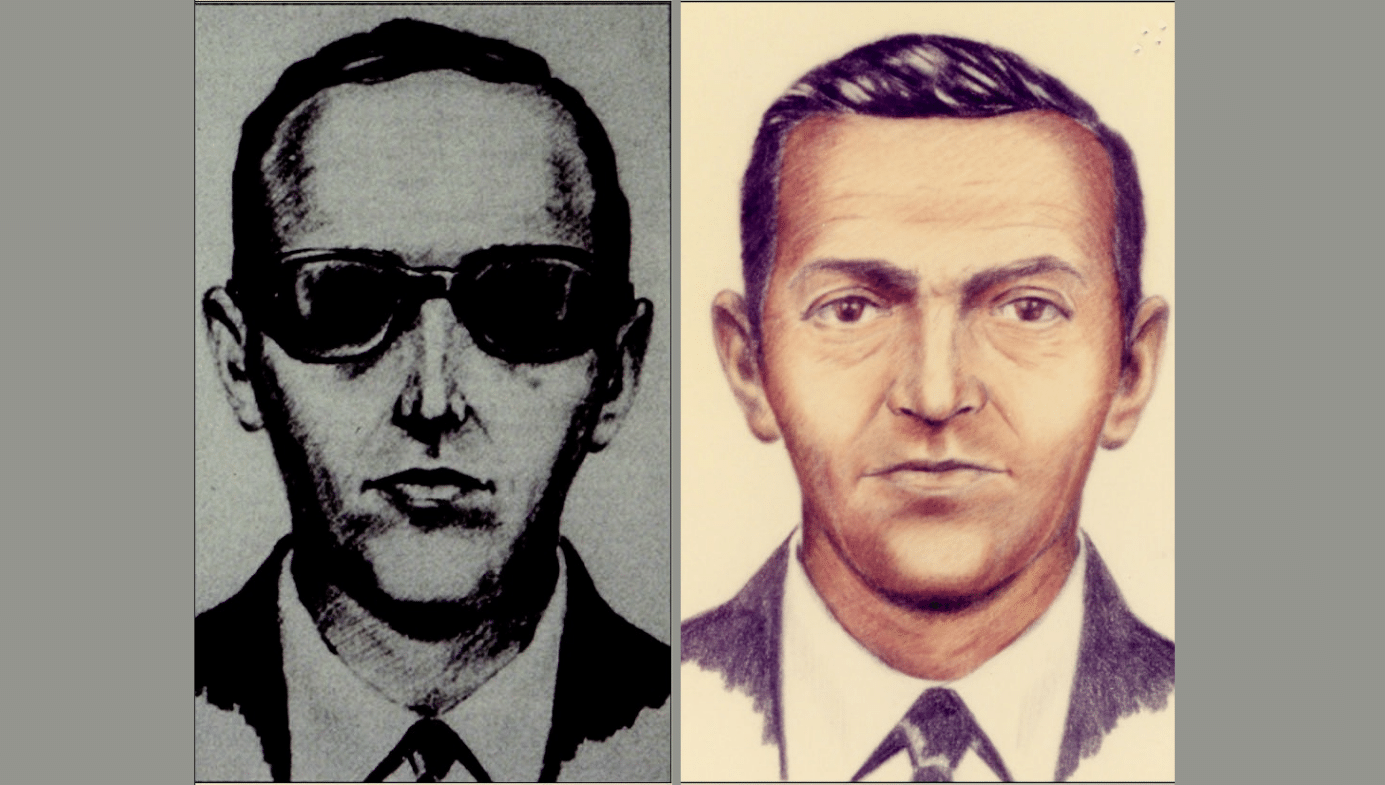

On November 24th, 1971—50 years ago today—a man known only by his alias Dan Cooper strapped himself into a parachute and leapt from the Boeing 727 he had hijacked over the Pacific Northwest clutching a bag stuffed with ransom money. Popularized as “D.B. Cooper” after the press misidentified him, the hijacker’s real name was never discovered. Despite a 45-year FBI investigation that was finally mothballed in 2016, his body was never found, his fate is still unknown, (most of) the ransom money was never recovered, and although theories abound, his crime remains the only unsolved instance of air piracy in aviation history.

Shortly after the Northwest Orient Airlines flight departed from PDX in Portland, Oregon, for Seattle, Cooper handed a note to a 23-year-old stewardess named Florence Schaffner. The note said that he had a bomb and would destroy the aircraft and everyone on it unless he was provided with $200,000 in cash and four parachutes when the plane landed. It took a while for the FBI to meet these demands, so the pilot, William A. Scott, was forced to fly in a holding pattern over Puget Sound for two hours. When the plane eventually touched down in Seattle, the passengers and all but one of the stewardesses (22-year-old Tina Mucklow) were allowed to leave. Cooper was given his parachutes and a canvas knapsack containing 10,000 $20 bills.

At about 7.40pm, after discussing his flight plans with the cockpit crew (captain, co-pilot, and flight engineer), Cooper ordered the plane to be flown to Reno, Nevada. He sent Mucklow to the cockpit and ordered her to lock herself in with the crew. Now he was alone in the plane’s cabin. At about 8pm, the airstairs at the rear of the plane opened and he threw himself into the Washougal Valley, in the southwest part of the state of Washington, never to be seen or heard from again.

D.B. Cooper was hardly the first person to hijack a jetliner. In fact, he was a bit of a late adopter. This was the golden age of skyjacking, and the crimes of Cooper and others who captured commercial flights in the hope of securing monetary or political reward not only transformed airport security, they also transformed aviation fiction.

II.

Strictly speaking, I took my first airplane flight in the spring of 1958. At the time, Frank Sinatra’s Come Fly With Me was the top-selling album in the US, and my father and mother (who was pregnant with me at the time) flew back to Oregon from England, where they had lived during most of my father’s four-year Air Force stint. I was conceived in Teddington, a suburb of London. My older sister (alive and well today) was born there, as was my older brother (who spent all three months of his life there, after which he was flown to Oregon, his only plane trip, to be buried in the same cemetery where his parents now repose).

This was an era when airplane travel still had an aura of romance, which made it a rich source of material for all kinds of pop cultural properties, not just Frank Sinatra songs. Marc Camoletti's hugely successful 1960 stage play Boeing Boeing tells the story of a Parisian bachelor dating three airline stewardesses at once. For a while, it was listed in the Guinness Book of World Records as the most performed French play in the world, and in 1965, Paramount Pictures released a film adaptation starring Tony Curtis and Jerry Lewis. Quentin Tarantino is said to be a fan.

Speaking of Tarantino, early in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, a film set in 1969, he delivers a shot of an attractive young stewardess (there was no other kind back then) climbing the spiral staircase of a Pan Am 747 to the first-class lounge where up-and-coming actress Sharon Tate (played by Margot Robbie) is dancing with a handful of other glamorous jetsetters. This counterpoints the shots of has-been alcoholic actor Rick Dalton (Leonardo DiCaprio) being driven around Los Angeles in a Cadillac by his unemployed stuntman pal Cliff (Brad Pitt). In Tarantino’s shorthand, jet travel signifies who’s hot and who’s not in Hollywood.

The 1963 film Come Fly with Me was based, not on Sinatra’s album, but on Bernard Glemser’s 1960 novel, Girl on a Wing, described by its paperback publisher as “The no-holds-barred novel of the stewardesses who swing in the sky—and on the ground!” The 1969 film The Stewardesses remains the most profitable 3D film ever made (though far from the highest grossing). Coffee, Tea or Me?, a 1967 novel credited to two airline stewardesses, Trudy Baker and Rachel Jones (but actually written by American Airlines PR man Donald Bain), went through numerous printings in the late 1960s and early 1970s. And in 1968, 10 years after Frank Sinatra released Come Fly With Me, the Beatles released their eponymous “White Album,” the first track of which opens with the sound of a Vickers Viscount turboprop jet landing on a runway, a sound that recurs throughout the song and introduces the next one. Air travel was one of the few aspects of the Sinatra era that retained its hipness in the era of The Beatles.

Other musical odes to air travel included Peter, Paul and Mary’s “Leaving On a Jet Plane” (written by John Denver), Marc Lindsey’s “Silver Bird,” the Steve Miller Band’s “Big Old Jet Airliner,” Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Travelin’ Band,” Gordon Lightfoot’s “Early Morning Rain,” Crosby, Stills and Nash’s “Just a Song Before I Go,” Susan Raye’s “L.A. International Airport”—the list goes on and on.

I took my first airplane trip as a non-fetus the day I turned 13. I remember the experience vividly because, for many Americans of my generation, your first airplane trip was a rite of passage, like your first sexual experience—something you never forgot. Back in those days, my family drove up from Portland, Oregon, to Lynnwood, Washington, every summer to visit our cousins who lived in that suburb of Seattle, which was home to hundreds of Boeing workers. My cousin, Sam Marthaller, born the same year as me, became a Boeing employee in the 1980s and spent much of his life working there (he died in 2017). In the summer of my 13th year, my parents, knowing what an airplane nut I was, decided to buy me a one-way ticket to Seattle for my birthday. Naturally, they couldn’t afford to fly our whole family there (see the above-referenced Derek Thompson article for an excellent explanation of why air travel in America was so expensive until the late 1970s).

And so, on Monday afternoon, August 16th, 1971, my parents drove me to PDX and placed me aboard the Northwest Orient Airlines flight that D.B. Cooper would commandeer exactly 100 days later. The rest of the family would drive up to join me the following day. Back then an unaccompanied minor aboard an airplane received a lot of attention from the airlines. I was given a pair of tin pilot’s wings, several Northwest Orient stickers and decals, a few postcards featuring photographs of airplanes, and even some swizzle sticks featuring the company’s logo. I cherished all of this stuff and saved it for years in the bedroom of the house I grew up in. It probably contributed to my interest in airline fiction. I read a lot of it in the 1970s.

In the middle of the 20th century, several pilots-turned-novelists rose to prominence primarily on the strength of their airplane fiction. They were nearly as commonplace as lawyers who write legal thrillers are today. Among the most famous of these was Nevil Shute (birth name: Nevil Norway), who was not just an airplane pilot but also an aeronautical engineer (in the 1920s and ‘30s he worked for Vickers Ltd, the company that manufactured the jet engine heard on The White Album). Shute’s novels tended to emphasize the technical details of airplane flight over external dangers such as hijackers or daunting mountain ranges. No Highway, Shute’s 1948 aviation novel, deals with … metal fatigue. Believe it or not, it became a nail-biting film experience when it was brought to the big screen in 1951 as No Highway in the Sky, directed by Henry Koster and starring James Stewart and Marlene Dietrich.

In 1954, several de Haviland Comets (the world’s first commercial jet airliners) suffered catastrophic mid-air break-ups that were eventually determined to have been caused by exactly what Shute had predicted: metal fatigue. Many of Shute’s other novels—Marazan, Landfall, Round the Bend, In the Wet, The Rainbow and the Rose, Pastoral, An Old Captivity, etc.—deal, directly or indirectly, with airplane flight. They are filled with the kind of technical details that a non-pilot writing an aviation novel might not think to include (e.g., “It is better in the tropics to keep fuel tanks always full to prevent condensation troubles.”).

Shute was writing about airplanes at a time when air travel was still both glamorous and fraught with peril. The cover of Life magazine’s August 25th, 1958, edition features a pair of smiling stewardesses, who the cover story describes as the “Glamour Girls of the Air.” But the same issue carried a separate story about the mysterious August 14th crash of KLM passenger flight 607-E, which went down into the sea shortly after leaving Shannon, Ireland, killing everyone on board. It also included a story about the August 15th crash of Northeast Airlines flight 258 in Nantucket, Massachusetts, which killed 25 of the 34 people on board.

If we ignore Richard Bach, the author of Jonathan Livingston Seagull and other dreadful books, then probably the most successful American pilot-turned-aviation-novelist was Ernest K. Gann. Gann’s first novel, Island in the Sky (1944), tells of a military airplane that ends up going wildly off course before crashing in a snow-covered frontier. His next novel, Blaze of Noon (1946), tells of the aviators who pioneered the delivery of airmail in the United States back in the 1920s. Other aviation novels by Gann include In the Company of Eagles (1966, about the fighter pilots of World War One), Band of Brothers (1973, about the investigation into the crash of a commercial jet in Taiwan), and The Aviator (published in 1981, and with a plot at times so similar to the plot of the Tom Hanks film Cast Away that I’m surprised Gann wasn’t given some sort of story credit).

Back in the 1940s and the early 1950s, nearly every new publishing season brought another round of airplane novels that were actually about the technical details of keeping an airplane aloft or an airline business afloat. In 1974, Roberta J. Forsberg wrote a study of two of the best writers in this genre in a book entitled Antoine Saint-Exupery and David Beaty: Poets of a New Dimension. The subtitle says it all. For much of the 20th century, airplane flight was viewed by many as an almost mystical experience. Indeed, a major character in Nevil Shute’s 1951 novel Round The Bend invents a new religion that blends aviation with ethical principles. In one of his sermons he tells the listeners:

Do not think there is a jealous God who stretches out a peevish hand to take an aeroplane and throw it to the ground. Aeroplanes come to grief because of wrong cravings and wrong hatreds and illusions in men’s hearts. One of you may say, “I have not got the key to the filler of the oil tank. I cannot find it. I looked yesterday and there was plenty of oil. It is probably all right today.” So accidents are born, and pain and suffering and grief come to mankind because of the sloth of men…

By the late 1950s, however, air travel was beginning to seem less like a new frontier and more like a playground for the rich and fashionable. Gossip columnist Igor Cassini coined the term “jet-set” to describe these thrill-seeking international travelers which replaced the outmoded term “café society” (curiously, Igor’s brother, the couturier Oleg Cassini, once designed the uniforms for the stewardesses of National Airlines). As a result, airplane fiction began to change its focus from the mechanics of flying to the lives and loves of the wealthy people who traveled for pleasure, globe-hopping from one exciting destination to the next. Naturally, virile airline pilots and sexy young stewardesses figured prominently in these tales.

Even when these fictions were thrillers, however, they tended to avoid criminality. Runway Zero-Eight, Arthur Hailey’s first novel (co-written with Ronald Payne and John Garrod and technically a novelization of a TV movie he had scripted), tells the story of a chartered jet carrying a bunch of Canadian sports fans from Toronto to Vancouver for a big game (the sport is never revealed). Shortly after the stewardess serves dinner, the passengers who opted for the salmon over the pork begin suffering agonizing bouts of food poisoning (foul play is never even suggested). Unfortunately, both the pilot and the co-pilot opted for the salmon and become debilitated as a result. Before the magnitude of the looming disaster has been disclosed to the passengers, a doctor aboard the plane (which is now flying on auto-pilot) makes a discreet effort to find out if any of the passengers have experience piloting a plane. Eventually, he finds someone who flew fighter jets in the war (which would be highly unlikely nowadays but not in the mid 1950s, when World War II veterans were commonplace everywhere). Alas, the fighter pilot flew single engine planes that were roughly as complex as a 1956 Volkswagen Beetle, and he has no experience whatsoever in the cockpit of a jumbo jet. Fortunately, with the aid of a scrappy stewardess who has a decent working knowledge of the jet’s instrument panel, the ex-fighter pilot lands the plane safely in Vancouver.

Published in 1959, the book was fairly typical of the airplane fiction of its era—air travel is portrayed as a somewhat upscale venture, crime plays no role, and the heroes are a rugged ex-military pilot and a sexy young stewardess. By 1968, when he published the phenomenally successful Airport, Hailey was strewing his airplane fiction with insurance fraudsters, suitcase bombers, and stowaways. And that became the template for much of the airplane fiction that would follow (it also became the template for a franchise of increasingly ridiculous films, all of which would be spoofed in the hugely successful 1980 comedy Airplane!, which grossed $171 million on a budget of $3.5 million). So, what turned the airplane novel into just another genre of crime fiction?

III.

According to The Skies Belong To Us: Love and Terror in the Golden Age of Hijacking, Brendan I. Koerner’s excellent study of the subject, “Prior to the spring of 1961, there had never been a hijacking in American airspace.” That ended on May 1st, 1961, when a Miami electrician hijacked a commuter plane bound for Key West and forced it to fly to Cuba. The hijacker was arrested in Cuba and the plane was allowed to depart shortly thereafter. America’s first hijacking, according to Koerner, delayed the plane’s arrival in Key West by only three hours. It was a minor inconvenience and no one at the time saw it as the harbinger of a horrible new trend.

But less than three months later, an Eastern Air Lines flight was hijacked, again to Cuba. Eight days after that, a passenger attempted to hijack a flight from Chico, California to Smackover, Arkansas, but was foiled by fellow passengers who attacked and subdued him. Two days later a Continental Airlines flight out of Phoenix was hijacked. Up until 1961, hijacking wasn’t even a recognized federal crime in the US. Those who committed it could only be charged with kidnapping and other related offenses. In September 1961, to put an end to this mini-spree, Congress quickly passed a bill making air piracy a capital offense, and President Kennedy signed it into law. That seemed to do the trick—at least for a while. No additional hijackings occurred in American airspace for the rest of the year. Nor were there any hijackings in 1962, 1963, or 1964.

Alas, the lull ended in 1965, just as the peace-and-freedom movement was beginning to flower. A number of sadly deluded Americans convinced themselves that Fidel Castro was creating a socialist paradise in Cuba, and they began hijacking planes to Havana. These utopia-seekers had no other way of reaching Cuba, because the American government’s embargo made it impossible to travel there legally. As so often happens with those who seek paradise on Earth, these hijackers mostly found only greater misery. Castro despised the hijackers, and was convinced they were CIA spies. After deplaning in Havana, the hijackers usually spent weeks being interrogated and tortured by Cuba’s secret police.

If the hijacker could convince his inquisitors that he was no spy, he was sent to live in a dormitory where each American was allotted 16 square feet of living space. At times, as many as 60 Americans occupied this dormitory. Less fortunate hijackers were sent to work in sugarcane fields under miserable conditions. If they objected to their treatment or tried to escape, they would be hacked to death with machetes, or dragged through a cane field until the flesh was stripped from their bodies. The US government tried to warn potential hijackers of these dangers, but during the Vietnam War era the US government was deemed by many to be less credible than the Castro regime.

By the late 1960s, so many flights were being hijacked to Cuba that the Federal Aviation Administration considered building an exact replica of Havana’s Jose Marti International Airport on the coast of Florida. The pilots of hijacked airplanes would then land their jets at this Potemkin airport and American air marshals dressed as Cuban authorities would come out to greet the hijackers with open arms, handcuffing and arresting them as soon as it was safe to do so. The plan never got off the drawing board.

Although American government officials were eager to put an end to this rash of hijackings, they received fierce opposition from an unexpected source—the airlines themselves. Air travel back then was still primarily a rich man’s mode of transportation, and the airlines feared that if they inconvenienced their wealthy customers with long and humiliating luggage-searches, X-rays, and pat-downs, their profits might begin to suffer. Generally speaking, it was less expensive for the airlines to put up with the occasional detour to Cuba than it would have been to institute stricter security protocols. Castro charged the airlines $7,500 before he’d allow a hijacked airliner to return to the US, but the airlines considered that fee a bargain compared to the cost of installing X-Ray machines at every terminal gate in the US. In fact, the official policy of all major airlines was to make no effort to thwart a hijacking attempt in progress. According to Koerner:

Every airline adopted policies that called for absolute compliance with all hijacker demands, no matter how peculiar or extravagant. … To facilitate impromptu journeys to Cuba, all cockpits were equipped with charts of the Caribbean Sea, regardless of a flight’s intended destination. Pilots were briefed on landing procedures for Jose Marti International Airport and issued phrase cards to help them communicate with Spanish-speaking hijackers. … Switzerland’s embassy in Havana, which handled America’s diplomatic interests in Cuba, created a form letter that airlines could use to request the expedited return of stolen planes.

Long before D.B. Cooper became a household name, plenty of other hijackers enjoyed their own moment of notoriety. Leila Khaled, an attractive member of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (categorized as a terrorist organization by the US State Department) became something of a media darling after she participated in the hijacking of a TWA flight to Damascus in 1969. Many media outlets seemed more interested in her good looks and fashion sense than in her criminal activity. Her face became so well known that she had to undergo multiple plastic surgeries in order to continue working as a hijacker. A year later, during the hijacking of an El Al flight from Amsterdam to New York City she pulled the pin on a grenade and attempted to blow up the plane in midair. Miraculously, the grenade never detonated. The first two 747s ever to suffer what aviation authorities call “hull loss” (irreparable damage resulting in a complete loss of the airplane) were destroyed by terrorists connected with the PFLP. One of those planes was hijacked by associates of Khaled in an effort (ultimately successful) to win her release from a British jail. Now 77 years old, she lives with her family in Jordan, but has occasionally accepted speaking engagements in the UK and Sweden.

In May of 1969, US Lance Corporal Raffaele Minichiello, who earned a Purple Heart for his service in Vietnam, hijacked a plane in Los Angeles and demanded to be taken to Italy, the country of his birth (he was angry because he believed the Marines had cheated him out of money he was owed). When he finally got there after several changes of airplane, he was greeted as a national hero. The Italians, like many others in Western Europe, despised American policy in Vietnam, and admired Minichiello’s willingness to speak out against the US military, even if his beef was just a personal one. Film producer Carlo Ponti wanted to make a film about Minichiello’s life. Teenage girls worshipped him as if he were a rock star. The Italian courts gave him a light sentence for his crime (18 months in prison) and refused to extradite him to the US. When he got out of jail he was offered a role in a spaghetti Western.

So, by the time D.B. Cooper commandeered Northwestern Orient Airlines Flight 305 in November 1971, air piracy was no longer a novelty. Not only was Cooper not the world’s first hijacker, he wasn’t even the first to attempt a so-called “parajacking.” Eleven days before Thanksgiving 1971, 26-year-old Paul Joseph Cini boarded an Air Canada flight from Calgary to Toronto with a parachute concealed in tightly wrapped paper and tied up with twine. No one on the flight paid much attention to his parcel because they were preoccupied by the shotgun and the dynamite he had also brought onboard. He shoved a stick of dynamite into the mouth of a stewardess and demanded to see the captain. Once inside the cockpit, he identified himself (falsely) as a member of the Irish Republican Army and demanded $1.5 million and passage to Ireland. The captain landed in Great Falls, Montana, where airline officials had scrounged together $50,000 in cash. Cini didn’t seem to notice that the ransom was $1.45 million short and forced the plane back into the air.

Cini had been planning this crime for a long time and had determined that the only way to successfully hijack a plane for money was to parachute out of it once the ransom had been delivered. Alas, Cini had tied up his parachute package too tightly. He couldn’t undo the knots in the twine. He asked the captain for help. The captain handed him a fire axe and suggested he use it as a cutting tool. Cini, apparently an idiot, set down his shotgun and reached for the axe, whereupon the captain kicked the shotgun away and wrapped his arms around Cini’s neck. Another crewmember grabbed the fire axe and brought it down on Cini’s head, fracturing his skull. Thus ended the world’s first parajacking attempt. Had he not been a bit overzealous with the twine, Cini might have reaped the fame and glory that would soon belong to D.B. Cooper.

IV.

So, if hijackings were so commonplace in the early 1970s, why does D.B. Cooper remain pretty much the only famous skyjacker in history—the only one, besides Khaled, who most people can identify by name? The answer is simply that when someone or something vanishes without a trace it defies the natural order of things. We’re used to a certain predictable narrative surrounding people, places, and events. They arrive, they exist for a while, and then they die and are buried. The RMS Titanic held a larger place in the world’s collective consciousness before Robert Ballard and his crew located its watery grave in September of 1985. For the 73 years before that, people were obsessed with the idea that a ship that was nearly three football fields long and as tall as a 17-story building had simply vanished without a trace, even though hundreds of people witnessed its sinking and lived to tell about it.

Plenty of famous aviators have died while pursuing their passion for flying—Wiley Post, Denys Finch Hatton, John F. Kennedy, Jr.—but none of these men retain the mythic status of Amelia Earhart who also appears to have died doing what she loved. We don’t really know what happened to Earhart because one day, like the Titanic, she simply vanished. And, unlike the Titanic, she and her airplane have thus far eluded all attempts to locate their remains. The same would appear to be true of D.B. Cooper. On Thanksgiving Day, 1971, he stepped out of the back end of a Boeing 727 in midflight and simply vanished. No one really knows what became of him, and that excites the human imagination. But, as Koerner points out in The Skies Belong to Us, Cooper’s fate is fairly easy to guess:

Experienced skydivers scoffed at the notion that Cooper could have survived his jump. The man seemed to know virtually nothing about skydiving, as evidenced by the fact that he jumped without a reserve chute and didn’t ask for any protective gear. The plane was traveling at roughly 195 miles per hour when Cooper exited, a speed that even experienced parachutists consider unsafe; it is possible that Cooper was knocked unconscious immediately after jumping. No professional skydivers attempted to jump from a Boeing 727 until the 1992 World Freefall Convention in Quincy, Illinois. One participant, who jumped at an airspeed of “only” 155 miles per hour, was amazed by the violence of the experience. “The first thing you noticed after exit was the heat from the jet engines and the smell of jet fuel,” he said. “There was a dead void, then the blast from jet steam. It felt like I was being tackled from behind.” Even if [Cooper] did survive the initial plunge through subzero air temperatures and pounding hail, the terrain below was lethal—nothing but hundred-foot-tall fir trees and frigid lakes and rivers. Like so many skyjackers before him, Cooper was probably too psychologically askew to have thought his plan all the way through.

Nevil Shute’s Round the Bend contains a scene in which an American criminal parachutes precipitously from an airplane into a terrain unknown to him but similar to what would have awaited Cooper in southern Washington. Shute’s description of what happened to Dwight Shafter might also describe what happened to Cooper 20 years later:

Shafter had bad luck; he fell on the tree tops, which checked him, and his parachute collapsed. He was perhaps fifty feet from the ground. The top branches broke beneath his weight after a moment and he fell through the branches to the forest floor, clutching at every branch as he fell. Finally he dropped helplessly from a height of about twenty feet and fell across a root. He broke his thigh in two places. That was the end of it for him.

Nonetheless, by disappearing into the ether, Cooper became a folk hero of sorts and the media couldn’t let his story die. As Koerner notes, “By now well-versed in the contagious nature of skydiving, the airlines and the FBI both braced for the inevitable post-Cooper outbreak. But they were still woefully unprepared for the utter mayhem of 1972.”

1972 was the nadir of 20th century passenger aviation in America. Six American commercial planes were hijacked in January of that year alone. In one incident, ex-Army paratrooper Richard LaPoint, clearly inspired by Cooper, collected two parachutes and a ransom of $50,000 in Reno, Nevada, and then forced the plane he had hijacked back into the air. He parachuted from the plane somewhere over a sparsely populated patch of Colorado. Alas, he made his jump wearing cowboy boots with nothing in the way of shock absorption in their soles. The landing damaged his feet so badly that he lay immobilized on the ground until the FBI, which had placed hidden tracking devices in the parachute, found him and placed him under arrest. When he was brought before a court for a preliminary hearing, the judge told him that, as a military veteran, he was entitled to free medical treatment for his damaged feet. As Koerner tells it: “The Vietnam War veteran grumbled a reply that resonated with untold thousands of ex-soldiers struggling to cope with life after combat: ‘How ‘bout some mental assistance instead?’”

Like Paul Joseph Cini, who unwisely set down his shotgun in the middle of a parajacking attempt, most of the hijackers of the golden age weren’t thinking especially clearly. Many of them, like LaPoint, were American military veterans whose psyches had been damaged in the Vietnam War. Some were recent draftees hoping to evade service in Vietnam. Many of them were racial minorities—primarily African- and Cuban-Americans. Air travel in America was mostly for Caucasians back in the 1960s and some racial activists equated airplanes with the white power structure. (After an Air France jet with 120 Americans onboard crashed in 1962, Malcolm X was delighted, telling a crowd of supporters: “I would like to announce that a very beautiful thing has happened. … I got a wire from God today … well, all right, somebody came and told me that he really had answered our prayers over in France. He dropped an airplane out of the sky with over 120 white people on it … and we hope that every day another plane falls out of the sky.”)

Often, these hijackers commandeered small commuter planes with a range of about 500 miles and then demanded to be taken to Europe or Africa or Vietnam. They might as well have asked to be taken to Shangri-La. One of the January 1972 hijackings was the work of a former mental patient. One was the work of an American military pilot who had carried out secret missions for the CIA in Laos and was wracked with guilt over it. Another was carried out by a desperate father trying to raise money for his son’s open-heart surgery (an FBI agent blew the man’s head off with a shotgun as he tried to flee with $200,000 in cash). One hijacker told the captain he wanted the jumbo jet to land in Coos Bay, Oregon, a small town with no major airports nor even a runway large enough to accommodate a commercial jet.

In April of 1972, a Mormon Sunday School teacher hijacked a United Airlines flight, collected a ransom of $500,000, and parachuted safely to the ground. Alas, he had worn no gloves and left his fingerprints all over the airplane, which made it easy for the FBI to identify and catch him. In June of ’72, former Army paratrooper Robb Heady jumped from a hijacked plane somewhere near Washoe Lake in Nevada holding a canvas bag containing $155,000 in ransom money. Some FBI agents, while cruising the area, found an empty car with a bumper sticker identifying the car’s owner as a member of the US Parachute Association. They staked out the car and arrested Heady when he came limping up to it (he was injured upon landing and lost the bag with the money as soon as he leapt into the jet wash). A Navy vet named Martin McNally jumped out of a hijacked plane clutching a bag containing $502,000 in cash. Like Heady, he lost his grip on the money as soon as he left the pressurized cabin. When the FBI tracked him down at his home a few days later, he had $13 to his name. An AWOL soldier hijacked a passenger plane in the skies above Sacramento and forced it to fly to San Diego, where he demanded to be given $450,000, a parachute, and … written instructions on how to skydive. These people were not criminal masterminds.

Cooper became a legend simply because his identity and fate both remain a mystery (on Loki, the new Disney+ TV series, viewers are treated to a reenactment of the Cooper hijacking and informed that Cooper was actually—surprise!—the old trickster Loki himself, as played in the Marvel Comic Universe by Tom Hiddleston). But Koerner displays little interest in Cooper. His book focuses much of its attention on Cathy Kerkow, who, along with her boyfriend Roger Holder, successfully managed to hijack a Western Airlines flight traveling from Los Angeles to Seattle in June 1972. The couple negotiated a $500,000 ransom payment, and arranged to have themselves flown, in several stages, to Algeria. The money was seized by the Algerian government when the couple arrived at the Algiers airport. Algeria at that time was the home of many American fugitives from justice, most famously Eldridge Cleaver, a founding member of the Black Panthers. Holder (an African American) and Kerkow thought they would be treated by the Algerians as heroes in the fight against American imperialism.

In fact, they were mostly treated like unwanted guests. Even the Black Panthers, who had a large presence in Algiers at the time, wanted nothing to do with them once it became clear that the Algerian government would not allow them to keep the ransom money. Broke and miserable, the pair eventually made their way to Paris under false names. Holder, never very psychologically robust, soon grew homesick and unstable. When he was approached one night by Paris police officers who probably just wanted to warn him not to loiter, he gave them the entire story of his exploits as a hijacker. He even gave them the address where he and Kerkow were then living. The police officers didn’t take him seriously and told him to go home. A few days later the Paris police reported the conversation to the American embassy. Outraged, the Americans demanded that Holder and Kerkow be arrested. The police raided the address Holder had given them, but he and Kerkow had already bolted. When they were eventually caught, the French courts refused to extradite them to the US.

France has a history of refusing to extradite suspects accused of politically motivated crimes. Instead, the French opted to put the hijackers on trial in Paris, under French law. While their case dragged out in court, Holder and Kerkow were ordered to remain in Paris. This proved to be agony for Holder, who longed to return to America, but not for Kerkow. She ended the sexual relationship with Holder and began to blossom as a darling of the Parisian leftwing intellectual set. She wore the latest fashions—she was fond of going braless beneath see-through tops—and quickly became fluent in French. Jean-Paul Sartre fell particularly hard for her and wrote a letter to the court urging leniency. She dated several wealthy Frenchmen in the film industry and became a good friend of Maria Schneider, Marlon Brando’s co-star in Bernardo Bertolucci’s 1972 cause célèbre, Last Tango in Paris. Bertolucci’s film made Schneider notorious worldwide just a few months after the Algiers hijacking made Kerkow notorious worldwide.

Enamored of European life, Kerkow had no desire ever to return to America. In 1978, while her case was still slowly working its way through the French judicial system, she slipped out of France and into Switzerland. Her whereabouts have remained a mystery ever since. According to Koerner:

The likeliest scenario is that Kerkow returned to France after obtaining false documents in Switzerland, then melted into French society under an assumed name. Perhaps she married a wealthy boyfriend, who arranged for her to obtain French citizenship and relocate to a provincial town where she would attract little notice. … After a few years of adjusting to her new milieu, Kerkow would have become indistinguishable from those around her.

Holder wasn’t quite as lucky. He was finally tried in Paris in 1980 and found guilty of hijacking and kidnapping. He was given a suspended sentence that required him to remain at large in France for five years. By now he was so sick of France that he probably felt as though he were serving hard time. He flew to America the day after his suspended sentence concluded, and was arrested by the FBI the moment he landed. He was 36 at the time. In March of 1988, after several more years of legal wrangling in America, he finally pled guilty to interfering with a flight crew, a much less serious offense than hijacking. After a brief stint in prison, he returned to California. On February 6th, 2011, he dropped dead of a brain aneurysm in his San Diego home. He was 62, a chain smoker, and had suffered from mental and physical maladies for much of the previous four decades, many of them stemming from his service in Vietnam. Kerkow, a former high school track star (she was a teammate of the legendary Steve Prefontaine), was always much healthier than her former boyfriend. Odds are that she is still alive. If so, she turned 70 in October of 2021, and is still sought by the FBI.

At the time of the hijacking, Kerkow was a young and extremely attractive hippie chick with an interesting back-story. The $500,000 ransom she and Holder extorted from Western Airlines was a record at the time. It’s difficult to explain why, in the media and the public eye, she never acquired the same glamour as Cooper, a bland-looking, middle-aged cipher who collected a ransom less than half of Kerkow and Holder’s and who almost certainly plummeted to his death after foolishly stepping out into the frozen void above the Washougal Valley. Everything we know for sure about Cooper occurred between 2.50pm and 8pm on November 24th, 1971. Not only does he have no back-story, he has almost no story at all. Just as Fred Astaire got more praise than Ginger Rogers, who did everything he did but backwards and in high heels, Kerkow surpassed Cooper in every aspect of the art of hijacking but remains largely unknown to most Americans (and no doubt hopes to keep it that way). This is one female pioneer that even feminists have no desire to celebrate.

V.

It should be noted that there are plenty of heroes in Koerner’s book—pilots, stewardesses, and others who willingly boarded hijacked airliners during refueling stops to relieve the original crew when they became too exhausted to go on (sometimes the original crew was relieved because it lacked the necessary experience flying international routes). Kerkow and Holder originally demanded to be flown to Hanoi, the capital of North Vietnam and a place extremely hostile to all things American during that era of the Vietnam War. Nonetheless, pilots Bill Newell, Dick Luker, and Don Thompson volunteered for the flight while the plane was being refueled in San Francisco. And, as Koerner writes, they weren’t the only brave ones:

Newell paged the senior stewardess on duty, Glenna MacAlpine, who was just about to depart for the weekend. When informed that the hijacked flight needed stewardesses, MacAlpine did not hesitate to volunteer; like Newell, she felt obligated to place herself in harm’s way. She made some calls and found three other “girls” willing to assist: Pat Stark, Chris Hagenow, and Deirdre Bowles. All were eating dinner with their husbands when asked to work a hijacked flight; all immediately rushed to the airport, knowing full well that the trip could lead them into a war zone.

But heroic pilots and stewardesses were no match for bombs and guns and other weaponry. By the end of 1972, the airlines and the Nixon administration had had enough. On December 5th, the Federal Aviation Administration declared that all passengers in American airports must be scanned with a metal detector before boarding a flight. Furthermore, all carry-on items had to be inspected before they could be brought on board. A short time later, the US and Cuba agreed upon a treaty that would return all future American hijackers to the US from Cuba. The new rules proved amazingly effective in curtailing hijackings of American airplanes. Not a single plane was hijacked in American airspace in 1973. Only one plane was hijacked (to Cuba) in 1974. Soon the golden age of hijacking became just a memory. Alas, the damage to aviation fiction was already done.

You can see these changes reflected in the popular fiction of the era. In Frederick Forsyth’s most famous novel, The Day of the Jackal, published in 1971 but set in 1963, a globe-trotting assassin checks most of his luggage in at the London airport, knowing there is little chance the authorities will inspect it and find the incriminating items inside. In 1963, airport luggage inspection was arbitrary and desultory. But in Forsyth’s most famous short story, “No Comebacks,” first published in Playboy magazine in 1973 and later used as the title story of his 1981 collection, another assassin, operating in 1973, knows better than to try to slip his murder weapon past airport security. Instead he hollows out a fat book on Spanish history, hides the pistol and silencer inside, and then mails it to himself at the hotel where he plans to stay while in Spain for his contract killing. Forsyth writes, “Airports were out—thanks to international terrorism every flight out of Orly was minutely checked for firearms.” Oh, what a difference a few years made to the assassination game!

By the dawn of the 1970s, almost all bestsellers about commercial airplanes were thrillers about terrorists, hijackers, or doomed flights that crash-landed in the Andes. But it wasn’t always thus. William Faulkner’s 1935 novel, Pylon, explores the lives of barnstorming pilots in the early 20th century. It appeared in the same year as Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s North to the Orient, an account of an aerial expedition she and her husband, Charles Lindbergh, took across the Arctic Circle. The book earned Lindbergh the first ever National Book Award for nonfiction. Her 1944 novel, The Steep Ascent, inspired a reviewer for Kirkus to claim: “The literature of flight has no more gifted contributor than Anne Morrow Lindbergh.” None of these books was about terrorism, hijacking, or doomed commercial flights.

To be sure, mystery writers seized upon the possibilities of felonies in the fuselage almost from the moment the Wright Brothers successfully executed the first flight of a heavier-than-air vehicle at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, on December 17th, 1903. Agatha Christie’s Death in the Clouds, published in the same year as Pylon and North to the Orient, is a mystery in which Hercule Poirot tries to figure out who murdered a French moneylender aboard a commercial flight from Paris to London. Isaac Anderson, reviewing the book in the New York Times on March 24th, 1935, noted that “murder in an airplane is by way of becoming almost as common as murder behind the locked doors of a library.” Nonetheless, back in the early 20th century, books exploring the felonious possibilities of air travel didn’t dominate the literature of flight the way they do now.

Airplane fiction had begun turning to crime a few years before D.B. Cooper’s rise to fame. The first hijacking novel published during the golden age of skyjacking was British author Desmond Bagley’s High Citadel, published in 1965. It’s the tale of a Communist agent who hijacks a passenger plane in a fictional South American country and forces it to crash land in the Andes. In 1964, when Bagley was writing the book, years had passed since the last hijacking in America. He may have felt that setting a hijacking tale in a sophisticated Western democracy would make it seem implausible. But, as the golden age began in 1965, Bagley’s book suddenly looked prescient. Arthur Hailey’s Airport, the bestselling novel in America in 1968, was a hybrid of old-style aviation concerns—bad weather, a pregnant stewardess (a firing offense back in the day), a lost United Airlines food truck, a runway rendered unusable due to a stalled Mexican jet—as well as more contemporary ones, like a bomb-carrying psychopath. But from about 1970 on, most of the novels dealing with commercial air travel were primarily thrillers.

David Harper’s underrated 1970 novel, Hijacked, tells the story of a commercial flight from New York to San Francisco that is hijacked by a person unknown (a stewardess finds a message written in orange lipstick in the bathroom: “I’ve hidden a bomb aboard this plane and can set it off anytime with a radio…”). Thomas Harris’s 1975 debut novel, Black Sunday (later a film directed by John Frankenheimer starring Robert Shaw and Bruce Dern), tells the story of Palestinian terrorists who plan to cause widespread death and destruction at the Super Bowl by blowing up a fictional version of the famous Goodyear blimp above the stadium. But the novel was clearly inspired by the golden age of hijacking. One of the main terrorists, Dahlia Iyad—a young and telegenic Lebanese terrorist known for her sense of style—seems to have been at least partially based on Leila Khaled. Iyad, like Khaled, specializes in airport-related terrorism. And the American pilot she recruits to execute her plan is, like so many of the hijackers of the golden age, a psychologically damaged Vietnam vet. Also released in 1975, Lucien Nahum’s Shadow 81 has all the elements of a golden age thriller: a disturbed Vietnam War vet with piloting experience, the threatened hijacking of an American commercial jet, and a $20 million ransom demand. Reviewers tended to be more keen on this novel than Harris’s. “A great plane robbery,” gushed a reviewer at Kirkus, “… improbable but you’ll forget all about that while you read it. … A grandiose story, to be sure, but fine seat-of-the-pants entertainment with not a moment to lose.”

Nelson DeMille’s 1978 novel, By the Rivers of Babylon, is about Palestinian terrorists who blow up one Concorde jet and force another to crash land in the desert. Thomas Block’s 1979 novel Mayday (co-authored with DeMille) tells the story of some commercial airline passengers who must try to land the plane themselves after the captain and crew have been killed by an errant missile that struck the cockpit. Block produced several other aviation thrillers, including 1982’s Skyfall (in which a commercial jet is hijacked), and 1984’s Forced Landing, a smorgasbord for hijacking fans, which includes the hijackings of a submarine, a floating aircraft carrier museum, a Learjet, and a DC-9. The Fourth Angel, a thriller by Robin Hunter (a pseudonym for British historian Robin Neillands) tells the story of a passenger-plane hijacking and its violent aftermath. In Walter Wager’s 1987 thriller 58 Minutes, terrorists take over JFK airport in New York City and attempt to crash planes from the air-traffic control tower (if that sounds familiar, it’s probably because this book was the source of the film Die Hard 2, released in 1990).

One of the first prominent novels to incorporate an airplane hijacking into its plot was James Hilton’s Lost Horizon, published in 1933. But the word “hijack” appears nowhere in Hilton’s book. According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, the term first appeared in print in 1923. At that time it was used exclusively to describe the act of stopping a vehicle (usually a truck) on the highway and stealing it from its rightful owner (this happened fairly regularly in the US during Prohibition, when trucks carrying substances that could be used to make alcohol were often stopped and pirated by criminal gangs). The term is believed to have derived from the phrase “Hold ‘em up high, Jack!” supposedly uttered by the criminals who perpetrated the crime. In any case, the word hijacking wasn’t widely used to describe acts of air piracy until the 1960s.

Throughout Lost Horizon, the characters refer to their crime as a kidnapping, but the word sounds awkward in that context. Since none of the characters are held for ransom nor prevented from leaving Shangri-La (the place they are eventually hijacked to), kidnapping doesn’t seem the right term. Nonetheless, that word was about all that was available to Hilton at the time (the portmanteau “skyjack” didn’t come on the scene until decades later). What’s more, the plane hijacking in Lost Horizon is less in the nature of a crime and more in the nature of a convenient plot device for getting Hilton’s characters into a mythic paradise on Earth. If he were writing the book today, his characters would probably be transported to paradise via some form of virtual reality (as in the Amazon Prime TV series Upload, or various episodes of Black Mirror) or a wormhole (as in Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure, Interstellar, and many others) or some other fantasy portal. But back in 1933, airplane travel was still novel enough to be used as the gateway into a fantasy realm. Shangri-La and the interior of an airplane were almost equally mysterious to your average American reader back then. So, although the book includes a crime, it is still part of the airplane-flight-as-spiritual-experience genre of pop fiction.

With the obvious exception of the atrocities of September 11th, 2001, hijacking hasn’t been a huge problem in the US since the early 1970s. Nonetheless, when popular fiction deals with commercial air travel these days it generally includes a major element of criminality (see, for example, Falling by T.J. Newman, The Flight Attendant by Chris Bohjalian, Before the Fall by Noah Hawley, or The Last Flight by Julie Clark, all of which were published within the last few years). Gone are the days when aviator/authors such as Nevil Shute and Ernest K. Gann and Paul Beaty wrote about airplane travel as if it were an almost spiritual experience. That type of novel lost its hold on the public’s imagination when men like D.B. Cooper (and women like Cathy Kerkow) began boarding airplanes with a nefarious purpose in mind. The golden age of hijacking only lasted from 1965–1972, but its impact on popular culture endures.