Theodor Adorno

The Cold War’s Morbid Sage: Theodor W. Adorno and the Philosophy of 'Post-Existence'

Adorno was smuggling a work of social analysis full of difficult philosophical references into his readers’ reach by disguising it as literature.

While Radio Free Berlin was broadcasting Nikita Khrushchev’s secret speech, Peter Gente went to the cinema. As the radio waves rose into the evening sky, informing listeners on both sides of the divided city about the crimes of Stalinism, the curtain opened on Beauties of the Night, a comedy by René Clair about a young composer escaping into dreams of success and beautiful women, losing his connection to reality—until the end of the film, when he comes to his senses just in time to face real life. Gente was ecstatic, and gave the film a grade of “1+” in his culture diary. He went to the cinema often in those days, and also visited Berlin’s theatres, concert halls, and cultural centres. He had discovered his passion for culture after moving with his parents to the metropolis from the Soviet-occupied provinces. He began reading novels with the zeal of a late bloomer, and invested what money he earned at his summer jobs in admission tickets. Herbert von Karajan was the director of the Berlin Philharmonic. The Berliner Ensemble was an unbeatably affordable theatre at the unofficial exchange rate between Western and Eastern marks, and Brecht himself still watched from his box. And the cinemas showed films from France and Italy that broke with the aesthetics of the pre-war generation. On the eve of the Nouvelle Vague, Gente surrendered to the spells of Fellini, Hitchcock, Orson Welles, and Jean Cocteau. “Read bourgeois novels; consumed culture generally” was his summary of this period in a later self-criticism before his socialist comrades.

Karl Marx once commented that the Germans are philosophically contemporary with the present day, but not historically. In Gente’s life, too, major political events were only background noise. Although he lived at the epicentre of the Cold War, he hardly seems to have noticed Khrushchev’s February 25th, 1956 speech, which heralded a thaw in the East and a disenchantment among the intellectual left in the West. But perhaps Berlin was precisely the wrong place to develop a stable sense of reality. There were too many realities coexisting here: the ruins of the World War, and the monuments of the post-war economic miracle; the Kurfürstendamm in the West with its cafés full of buttercream cakes, and the Stalin-Allee in the East with its socialist gingerbread housing blocks. To Maurice Blanchot, whom Gente later counted among his favourite authors, Berlin “was not … just one city, or two cities,” but “the place in which the question of a unity which is both necessary and impossible confronts every individual who resides there, and who, in residing there, experiences not only a place of residence but also the absence of a place of residence.”

This is what it sounds like when a geopolitical situation invites metaphysical speculation. But, in 1956, Gente did not yet see the world in the light of theory. In a round script that betrays his youth, he kept a record of his evenings at the cinema and the theatre, and the minimalistic prose of his lists seems to quiver with pent-up desire. Gente was burning to find a place for himself in the world of the arts, and his readings soon influenced him to limit his search to the canon of high culture. In the year of the thaw, however, his taste had not yet matured. His diary mixes musicals with auteur cinema, Puccini with Hollywood and Brecht. It was up to him to discover a common denominator. In the meantime, he awarded the performances grades from 1 to 5—the scale used by German secondary schools, including the one he had recently left. The numbers were a relatively modest instrument of cultural criticism, taking no notice of highbrow or lowbrow categories. At the same time, Susan Sontag, negligibly older, was already jotting savvy mini-reviews in her diary as she made her own cultural rounds in Chicago. Gente’s marks went no higher than the superlative ‘1++’ for Giorgio Strehler’s adaptation of Harlequin, Servant of Two Masters, performed by the visiting Piccolo Teatro of Milan, and no lower than the moderate ‘3’ for Puccini’s La Bohème. He was an easy grader who repeatedly had to expand his scale upwards because, worshipper of culture, he had started out awarding too many 1s.

The following year, in 1957, Gente had an awakening. It occurred, however, not in the cultural sphere where he was seeking his future, but at the base, in wage labour. The scene is symptomatic of the young West Germany, which was already approaching full employment in the second half of the 1950s. On the assembly line of the Siemens factory in Spandau, where Gente worked to support himself while studying law—in accordance with his father’s wishes—he listened to two of his fellow students talking about a certain Adorno, whom they seemed for some reason to consider absolutely essential. Exactly what it was that captured his attention, he couldn’t remember later on. But the impression it made was certainly deep. “Adorno challenged earlier life,” Gente’s later self-criticism states tersely.

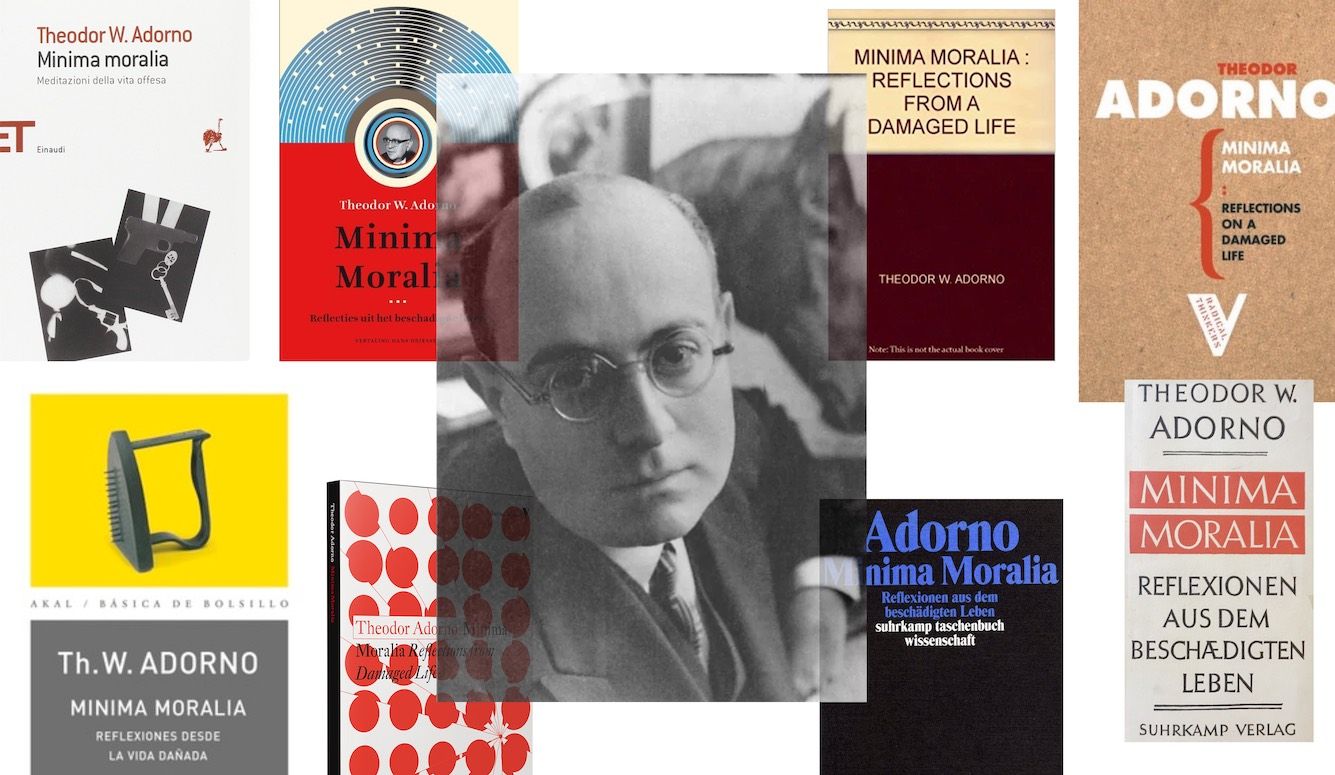

He got a copy of Theodor W. Adorno’s best-known book, Minima Moralia (1951), and couldn’t put it down, although he understood hardly any of the German philosopher’s impenetrable aphorisms. Yet the author, claiming that only thoughts “which do not understand themselves” can be true, apparently saw the hermetic tone as part of his message. The difficult language, yielding its meaning only to patient reflection, contributed to the influence of a book which made the books Gente had read before it seem irrelevant.

In 1957, Adorno’s “reflections from damaged life,” as Minima Moralia’s subtitle calls them, were still an insider tip. Six years after its publication, there was little to indicate that the book would be a philosophical hit, selling over 120,000 copies to date. In the middle of the post-war boom, between Opel Rekords and ice cream parlours, Gente was unsettled by it—by the way of thinking of a little-known Frankfurt philosophy lecturer who saw only disaster wherever he looked. “Life does not live,” reads the epigram, like a warning, on the first page; the pages that follow contain variations on that paradox. Condensing his experience of American exile into miniatures, Adorno exposes modern life as a state of deception. What seems to be alive and authentic is in reality long dead; the apparent aspiration to progress is caused by a ghostly compulsion to keep moving. It is a post-cataclysmic world we are living in. “The disaster does not take the form of a radical elimination of what existed previously,” a key passage reads—“rather the things that history has condemned are dragged along dead, neutralized and impotent as ignominious ballast.”

Hence the macabre atmosphere of Minima Moralia: its pages are populated by the undead. Among the figures whose eerie “post-existence” Adorno exposes are the achievements of the preceding bourgeois era—such as liberalism, socialism, and the hospitality industry, which reached a state of rigor mortis with the advent of room service. Adorno discovers the ghastliest signs of decay in the tiniest details of day-to-day life—hence his now famous observations that the inhabitants of the Enlightened hemisphere no longer know how to give gifts, to be at home in their homes, or to close a door. “The world is systematized horror” is his judgement of the present. That condemnation had the sinister weight, two decades before Apocalypse Now, of Francis Ford Coppola’s Colonel Kurtz watching a snail crawl along a razor’s edge. Meanwhile, German radios played the sentimental songs of the Austrian rover Freddy Quinn.

Freddy Quinn performing a song from his 1957 EP, Voilà FREDDY!

In the depressing post-war atmosphere of 1950s Germany, Adorno made it plain that there was “no longer anything harmless and neutral”: his diagnosis of a society paralysed to death stood before the backdrop of the German genocide. Elsewhere, he wrote about the primal scene of the ghostly life: “In the concentration camps, the boundary between life and death was eradicated. A middle ground was created, inhabited by living skeletons and putrefying bodies.”

Images like these must have conjured up childhood memories in Peter Gente. Toward the end of the war, prisoners from a nearby labour camp had turned up in his German home town of Halberstadt. Children passed around the rumours of underground factories where these figures assembled aircraft—their parents said not a word about them. In return, Gente said nothing about his parents for the rest of his life. The rupture—precipitated not least by his reading of Adorno—was too deep for him to accord them any importance beyond rejection. As a result, only a few isolated facts are known about them. Gente’s father was a lawyer who had served as a lieutenant on the Eastern front and had been taken prisoner by the Red Army. His mother, from a “very anti-Semitic family,” contributed that heritage to the marriage. Gente remembered helping his mother carry his paralysed grandmother to the basement shelter during an air raid that destroyed large parts of Halberstadt in April of 1945. The family’s big house on the outskirts of the city was not hit. But when Gente’s father returned from Russia six years later, his career was ruined: a former member of the Nazi Party had no hope of advancement in the legal bureaucracy of East Germany. A short time later, the family had to flee to the West—allegedly because the father’s contacts with the American intelligence service had been exposed.

Along with an initially small but later fast-growing number of his generation, Peter Gente made Minima Moralia his breviary: a book that was digestible only in small portions, but one that could be consulted in every circumstance. The dons of German universities did not know what to make of Adorno’s “painfully convoluted intellectual poetry,” as Thomas Mann once called the book. As a result, the influential reading experiences were extramural. In his later professional life as a publisher at Merve Verlag, Gente would insist on making ambulatory books—readable in the train, “while travelling” or around town—no doubt influenced by his experience as an Adorno reader. “I carried Minima Moralia around with me for a good five years. Every day, always with me, a regular vade mecum [guide to life].” With his melancholy diagnosis of the present, Adorno instituted a new use for philosophy: his books replaced the volume of poetry in the young reader’s coat pocket.

Like Thomas Mann, the first critics to review Minima Moralia in the 1950s pointed out its poetic character. They either revealed the book to be “secretly a lyric poem,” or attested that “only a musician” could have composed it. Adorno himself later claimed, in an interview in Der Spiegel, to be a “theoretical person who feels that theoretical thinking comes extraordinarily close to his artistic intentions.” This was no doubt the reason for the book’s great success: it catered for the poetic demand of the post-war period. In the same year in which Minima Moralia was published, German poet Gottfried Benn noted that the poets had triumphed over the philosophers. Even the philosophers, he declared in his 1951 Marburg lecture on “Problems of Lyric Poetry,” now longed to write poems. “They feel that systematic, discursive thinking has reached an impasse at the moment; consciousness can bear at the moment only something which thinks in fragments; five hundred pages of observations on truth, apt though some sentences may be, are counterbalanced by a three-verse poem.” If this diagnosis is correct—and the number of new poetry magazines emerging in the 1950s suggests that it is—then Adorno and his philosophical aphorisms were aligned with the trend of the time.

Adorno himself would by no means have wanted his work to be misunderstood as a prose poem, however. He is known to have rejected philosophers “borrowing from literature,” and decried the resulting language as a “jargon of authenticity.” But Adorno went further: in a world which had passed through an apocalypse, he saw no future for poetry itself. After Auschwitz, in his notorious dictum—also dated 1951—writing poems was a barbaric act.

Was he carrying this idea to its logical conclusion in Minima Moralia? Was the book a subversion of the poetic form by discursive philosophy? Adorno was smuggling a work of social analysis full of difficult philosophical references into his readers’ reach by disguising it as literature. As the 1960s progressed, they took the bait. Although Gente continued to read novels, he no longer read them as edifying tracts. German author Michael Rutschky, who discovered Minima Moralia a few years after him, wrote that Adorno’s texts made “literary writing seem completely anaemic compared with philosophy.” Ten years after Benn’s premature declaration of victory, different circumstances prevailed: “theory”—now in the singular as a mass noun—had so thoroughly co-opted poetry that it was in the process of superseding it.

Excerpted, with permission, from The Summer of Theory: History of a Rebellion, 1960-1990, by Philipp Felsch, translated by Tony Crawford, © 2021 by Polity Press. Originally published in German as Der lange Sommer der Theorie, by Philipp Felsch, © Verlag C. H. Beck oHG, Munich 2015.