Bioethics

Rethinking Judith Jarvis Thomson’s Defense of Abortion

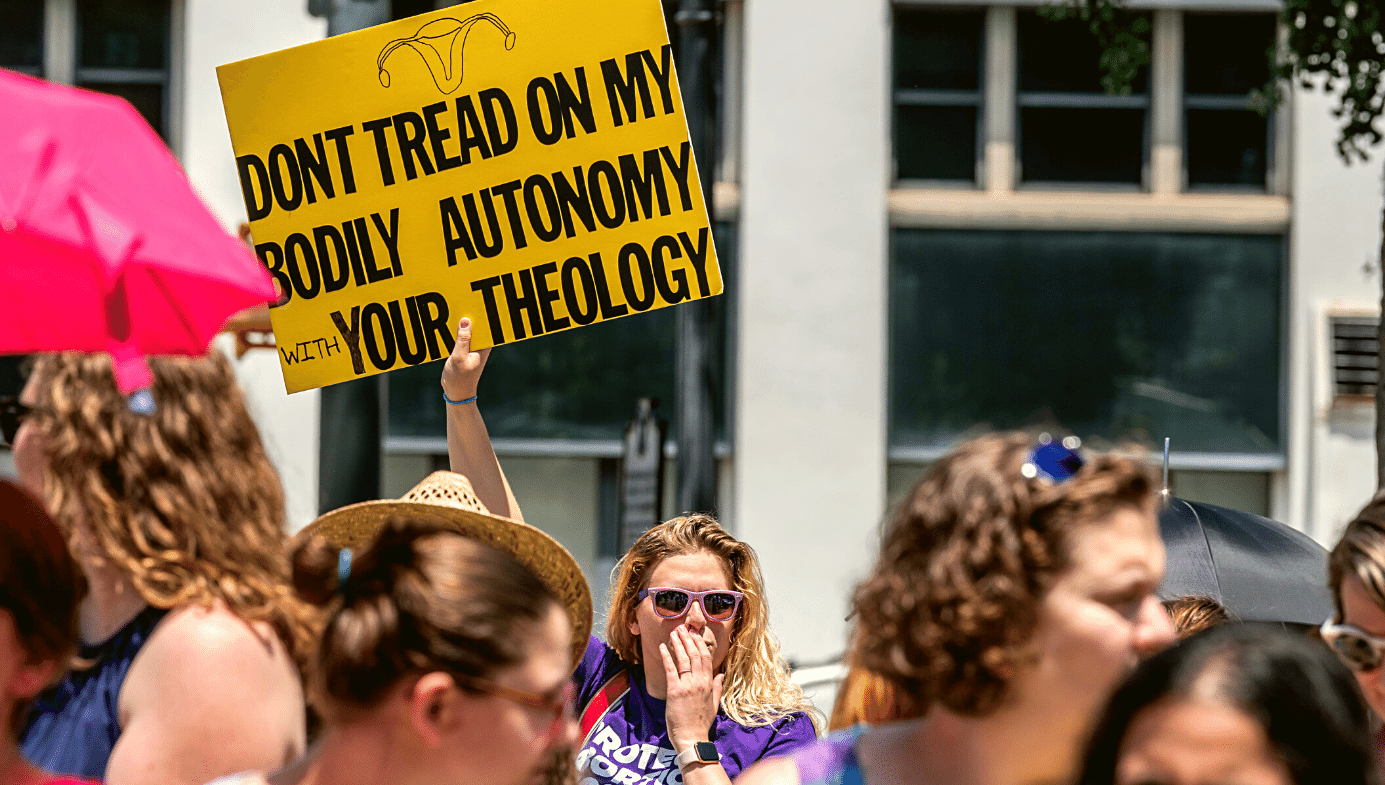

The abortion debate is primarily concerned with the bodily autonomy of the mother and/or of the fetus. The rights and duties of the father are seldom discussed.

One of the strongest arguments for the moral permissibility of abortion arguably comes from Judith Jarvis Thomson’s 1971 paper, “A Defense of Abortion.” Side-stepping entrenched debates over the metaphysical status of the fetus, Thomson argues that even if we grant full personhood status to the fetus, abortion would still be permissible. She supports this claim largely by way of her famous “violinist” thought experiment which goes like this:

You wake up in the morning and find yourself back-to-back in bed with an unconscious violinist. A famous unconscious violinist. He has been found to have a fatal kidney ailment, and the Society of Music Lovers has canvassed all the available medical records and found that you alone have the right blood type to help. They have therefore kidnapped you, and last night the violinist’s circulatory system was plugged into yours, so that your kidneys can be used to extract poisons from his blood as well as your own. [If he is unplugged from you now, he will die; but] in nine months he will have recovered from his ailment, and can safely be unplugged from you.

This extraordinary case appeals to the intuition that it would be morally permissible to unplug oneself from the violinist and allow him to die, since doing so would not in any way violate the violinist’s right to life. Indeed, the violinist would not have the right to make parasitic use of another person’s bodily autonomy in order to sustain his own life to begin with. By analogy, Thomson argues, a mother’s act of aborting her fetus would not constitute an act of doing/killing, and would not therefore constitute a violation of the fetus’s right to life. Rather, abortion should be understood as an act of allowing/letting die by the woman withdrawing her bodily autonomy and inherent life-sustaining processes from the fetus.

While Thomson’s thought-experiment has stood the test of time in countless undergraduate philosophy classrooms, biomedical seminars, and courtrooms for half a century now, the mechanics and details of the argument nonetheless warrant thorough re-examination. I want to argue here that Thomson’s argument in defense of abortion ultimately fails to acknowledge three essential metaphysical and morally relevant considerations:

- Flawed action-individuation.

- Special duties of parents.

- Special rights and duties of fathers.

Let us examine each in turn.

Flawed action-individuation

A crucial feature of Thomson’s argument is that the violinist case begins “mid-act.” The thought experiment traps us, wholly against our will, in an extraordinary scenario that has happened to no one else in all of human history. But this set-up is necessary to establish the conditions under which the decision “to unplug” will constitute an allowing/letting die of another adult human being rather than the killing and active termination of a life-sustaining process (and accompanying entity).

But in normal cases of consensual intercourse, the foreseeable causal chain and accompanying risks are set into motion by the original decision to have sex. So, if the woman later chooses to terminate that process, doing so would constitute a knowledgeable act of doing/killing rather than a mere allowing/letting die. Indeed, baked into the woman’s choice to have sex in the first place is the moral risk of setting off a predictable causal chain whereby another human life becomes wholly dependent upon her bodily functions to survive.

The everyday risks of consensual sex stand in dramatic contrast to the outlandish scenario in which some parasitic foreign entity suddenly attaches itself to a person’s pre-existing life-sustaining processes without that person’s will, knowledge, or foresight. Once we do a better job at filling in the causal back-story, it becomes evident that the life-sustaining process terminated in the abortive act finds its moral and metaphysical origin in the woman’s original choice to have sex.

Even if we disregard this argument, it isn’t even as if the abortion procedure itself is remotely comparable to an “unplugging,” let alone a mere allowing. As conservative pundit Matt Walsh succinctly notes:

The bodily autonomy argument doesn’t get you all the way to abortion. If a woman has a right to detach herself from her baby, to extricate herself from the situation, to remove herself from this dependent life-form, that would mean we would have to take the other life-form out of her. It would not mean that we would have to kill it before we take it out.

Hence, on standard philosophical accounts of doing versus allowing and killing versus letting die, the abortion procedure fails to satisfy standard conditions of mere allowing/letting die as Thomson’s analogy tries to suggest.

In these various ways, Thomson chops up and individuates the various parts of the causal process—from the woman’s initial choice to have sex all the way to the actual act of the abortion procedure itself—and ultimately appeals to the wrong moral intuitions, and with only a selected and highly curated fraction of the entire causal chain.

Special duties of the parents

Walsh further notes that Thomson’s violinist case is radically disanalogous from normal sexual intercourse and pregnancy cases insofar as the violinist is a complete stranger, suddenly thrust upon us against our will. This appeals to the intuition that a grave rights violation has taken place and that considerations of bodily autonomy should win the day.

However, the entity in question in the abortion debate is not some random stranger, but the mother’s own child. At issue here is the difference between allowing a random adult to die and killing one’s own child. This is no small matter. Were the child to be born, most people will maintain that both the mother and the father now have a particular responsibility to look after that child. They could not simply allow the child to starve to death because taking care of it would constitute encroachment upon their bodily autonomy.

Accordingly, if special duties to care for one’s own offspring and to not let them die apply during the moments immediately after birth, and if one’s offspring counts as a person while still in the womb (as the empirical data increasingly suggests and as Thomson grants for the sake of argument), then such special duties arguably trump bodily autonomy considerations for the same reasons in the womb as well.

Special rights and duties of fathers

The abortion debate is primarily concerned with the bodily autonomy of the mother and/or of the fetus. The rights and duties of the father are seldom discussed. Now, at first glance, any discussion of men’s rights in the present abortion debate might seem wholly inappropriate. After all, men are not the ones enduring nine months of pregnancy and all its accompanying physical and psychological hardships, reproductive complications, and many risks. Nevertheless, it is not as if the father’s role counts for nothing in the metaphysical and moral equation either. While the father's body does not carry the fetus during gestation, the contribution of the father's sperm is nonetheless a necessary condition for the fetus’s creation and therefore a necessary causal contributor to the accompanying rights and duties related to that living entity.

If we grant that a father has special duties to his offspring (once outside the womb), to care for and protect them or to at least pay child support, and we grant that the fetus is a person (either in virtue of the latest empirical evidence at some stage of gestation, or by stipulation according to Thomson), then the father’s special duties to care for and protect his would-be offspring within the womb deserve consideration. These may override the mother’s unilateral veto power in deciding to abort a fetus on bodily autonomy grounds. Either that, or it ought to be conceded that fathers have no special duties whatsoever to care for their offspring or to pay child-support once the child is born.

Conclusion

People don’t see with their eyes, they see with their concepts. Consequently, the more concepts people have, the more they will see. This claim, however, comes with an important caveat. It is important to remember that analogies are just that, analogies; and that any analogy, no matter how persuasive or clever or intuitively convincing at first glance, should be examined and scrutinized with extreme care and rigor before we use it as the basis for legislation, policy, or real-world action.