Iraq

Maternal Lessons in Politics from a Jewish Iraqi-American Ping Pong Champion

Democratic transformation generally comes from the ground up, not from foreigners bearing guns and gifts.

Whenever I would whine about some minor inconvenience while growing up in the suburbs of Columbus, Ohio, my mother would say, “You should try living in Iraq for a while.” It was a subject she knew something about. She was just four months old when about 200 of her fellow Iraqi Jews were slaughtered, while scores of others were beaten and raped, in a 1941 Baghdad pogrom (known as the Farhud) whose 80th anniversary was marked earlier this year. She and her family members remained safe because they’d been sheltered by Muslim neighbors, who traded houses with them during what became the most deadly anti-Semitic riot in Middle East history. As guests in a Muslim household, she explained to me, their protection became a matter of family honor for their hosts.

With the creation of Israel seven years later, and the subsequent defeat of the Arab armies that attacked the new Jewish state, the political situation became even more precarious for Iraq’s Jews. At one point, my mother’s father and older brother were arrested and jailed on charges of torching a local oil refinery. “We did not even know where the refinery was,” my mother recalled. When her father got sick in jail, he was transported to a hospital. After a month, both he and his brother were freed after the family bribed the appropriate authorities.

A decade later, my mother lived through the anti-monarchist Iraqi coup of 1958, in which Prince ‘Abd al-Ilah was killed, and his mutilated body was dragged through the streets behind a tank. Yet monstrous though these events were, Abdul al-Karim Qasim, the new prime minister, had a soft spot for the Jews. And so he became an improbably beloved figure among the scant members of Iraq’s Jewish community who hadn’t already fled to Israel or other destinations.

During this period, my mother was filled with nationalist fervor for the new Iraq and its leader. I know this not because she told me, but because when the US military invaded Iraq in 2003, one of its units stumbled upon a treasure trove of water-logged artifacts in the flooded basement of Saddam Hussein’s intelligence headquarters. Among the mouldy findings that were brought to the United States and restored were copies of a book on Jewish holiday liturgy written by my own grandfather, as well as the valedictorian speech my mother gave upon graduating from Frank Iny high school in 1959, just a year after Qasim had taken over the country. (Frank Iny operated until 1973, by which time it was the only Jewish school still operating in Iraq.)

The speech was essentially an ode to the Iraqi leader, whom she praised for restoring honor and freedom to the Iraqi people. “This year is different from previous years,” waxed my 18-year-old future mother, with her bouffant hairdo (yes, there are pictures) and starry-eyed idealism:

The mouths are smiling. The faces are bright. The hearts are happy. It is the first year of our blessed revolution ... Our sole leader Abdul al-Karim Qasim is the jeweled node of this nation and is the mighty thinking head who elevates us every day from one social revolution into another more glorious and more advanced. We strived and struggled to attain our freedom and our free thought. Our poet Mar’uf Al-Rusafi was right when he said: If there is an aspiration for people of a nation, free thought must be the highest aspiration.

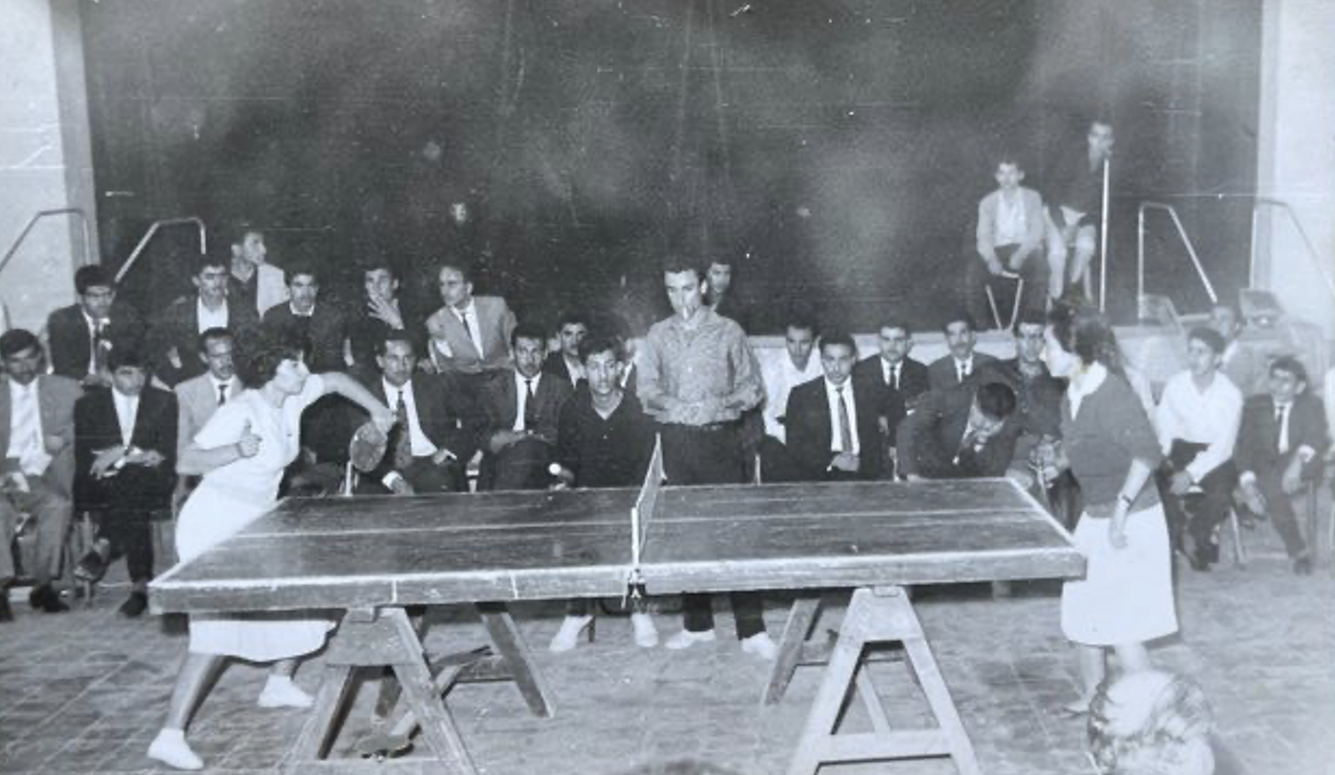

These were heady years for Iraqi Jews, as the country appeared to be on the cusp of a more liberal order. My mother was among the first Jewish women ever allowed to enroll in the University of Baghdad, where she studied Chemistry and even played sports. As a child, I poked fun at her about the “Baghdad U” athletics program. Unamused, she proclaimed her status as the university’s one-time ladies table-tennis champion, with trophies and photos to prove it (not to mention a wicked backhand slam retained from those glory days). She freely intermingled with Muslim students at the university, and even dated one for a time (though in secret).

Iraq’s liberal moment was, of course, short-lived. Qasim, while relatively benign to the Jews, went on to rule as an autocrat. He was overthrown and killed in 1963 in the so-called “Ramadan Revolution.” And the incoming Ba’athists were decidedly less enamored with the country’s Jewish minority.

“We were devastated,” my mother recalled. “I remember my friend singing a popular song in Arabic, My eyes are smiling but my heart is crying.” After graduating from university a few months later, she left Iraq, alone, following on my grandfather’s bribe to secure a student visa. She landed in Cincinnati, Ohio, where her brother had settled, and enrolled in a Masters chemistry program. Just weeks after that, her friends back in Baghdad informed her that there’d been yet another coup in Iraq, this one instigated by Nasserist military officers—though they didn’t yet know if it was good or bad for the Jews. Days later, the government shut the doors to Jews wishing to leave the country.

That same month, President John F. Kennedy was shot and killed in Dallas. My mother told me that her first thought was that tanks would soon be rolling down the streets of Cincinnati and other American cities, dragging the dead bodies of the President’s family members and advisors. Needless to say, that didn’t happen. And my mother got a lesson in how politics works in a democratic society.

Members of the Iraqi side of my family have always worshipped America. (My father, a Jew of European heritage, was born in the United States.) When I was a young child, my mother would refer to Iraq as “back home.” When she finally became a citizen in 1971, however, she announced that Iraq was no longer her home, and she vowed never to use that phrase again.

But the political attitudes that my relatives grew up with in the strongman-dominated world of Iraq proved stubborn. My grandmother, who lived in our home and didn’t speak a word of English, adored Ronald Reagan for what she described as his magnetic confidence and strength. As a teenager, I had a stereotypically sneering attitude toward the Gipper, and made my views plain during our political arguments. When Reagan won a second term, she told me, “See? I was right!” In the Arab world, victory and “strength” went together. That instinct from “back home” still held sway.

No one would accuse any of my Iraqi Jewish family members of being civil libertarians. According to the facile tropes of US political commentary, there’s often a polite fiction that presents immigrants as a unified political constituency. As anyone who grew up in an immigrant family can attest, this is nonsense. My mother once commented to me that Somali taxi drivers in Columbus, Ohio who refused to transport alcohol out of adherence to religious scruples should be deported. She also bought into conspiracy theories about Muslims trying to impose Shariah law on the United States as a whole. I told my American-born cousins that if any of our Iraqi parents found themselves heading America’s government, they might take inspiration from the methods of their late, beloved Abdul al-Karim Qasim.

In 2003, my mother and grandmother became giddy about the impending invasion of Iraq. “Let the Americans bomb my home in Baghdad!” exclaimed my grandmother, by then blind and feeble in her late 90s, along with muttered Arabic words of prayer, as if she would soon personally be storming the palace of Saddam Hussein. Every year, during the recitation of the Ten Plagues at Passover, she would wish a different plague on Bashar Assad and other notorious Arab leaders. All of this put her well at odds with the more liberal tendencies developing within late 20th-century American Jewry. (I once told my mother that in Hebrew School, I’d learned that at Seder, we take a drop of wine out of the cup when reciting each plague so as to lessen the joy we feel because of the suffering of the Egyptians who’d enslaved our forebears. “That wasn’t how we did the plagues in Iraq,” she shrugged.)

As thrilled as they were about George W. Bush’s plan to invade their former homeland, my older family members never believed the war would transform the country. “If these idiots think they’re going to install a democracy in Iraq, they’re crazy,” my mother said. By then, I was in a neo-con phase, and so the debating roles we’d played in the Reagan era were now reversed. But when it came to Iraq, she turned out to be correct. Democratic transformation generally comes from the ground up, not from foreigners bearing guns and gifts. Perhaps she knows more about democracy than I gave her credit for.

In the end, it didn’t matter much that our Iraqi-born relatives weren’t schooled in the latest political doctrines. They were focused on making a living. Having come from a country with no real democratic tradition, they never had interest in so much as running for dog catcher. But like many of the immigrants who come to the United States from other repressive dictatorships, they still appreciate the fruits of democracy. They know that in Afghanistan, the Taliban are the bad guys and the Americans were a force for good. And they never went in for those political word games, played on both sides of the political spectrum, that serve to muddle the difference between freedom and actual oppression. It’s something I think about when I hear right-wing populists and ultra-progressive critical race theorists alike pretend that our hard-won democratic institutions are a mask for tyranny.

Not only is democracy built from the ground up—it can be undone from the ground up. Like my mother said, these people should try living in Iraq for a while.