Free Speech

Inflammatory Anti-Racism

The fear of being branded with one of the most deadly contemporary sins has generally ensured a pusillanimous collapse by corporations, institutions, and individuals.

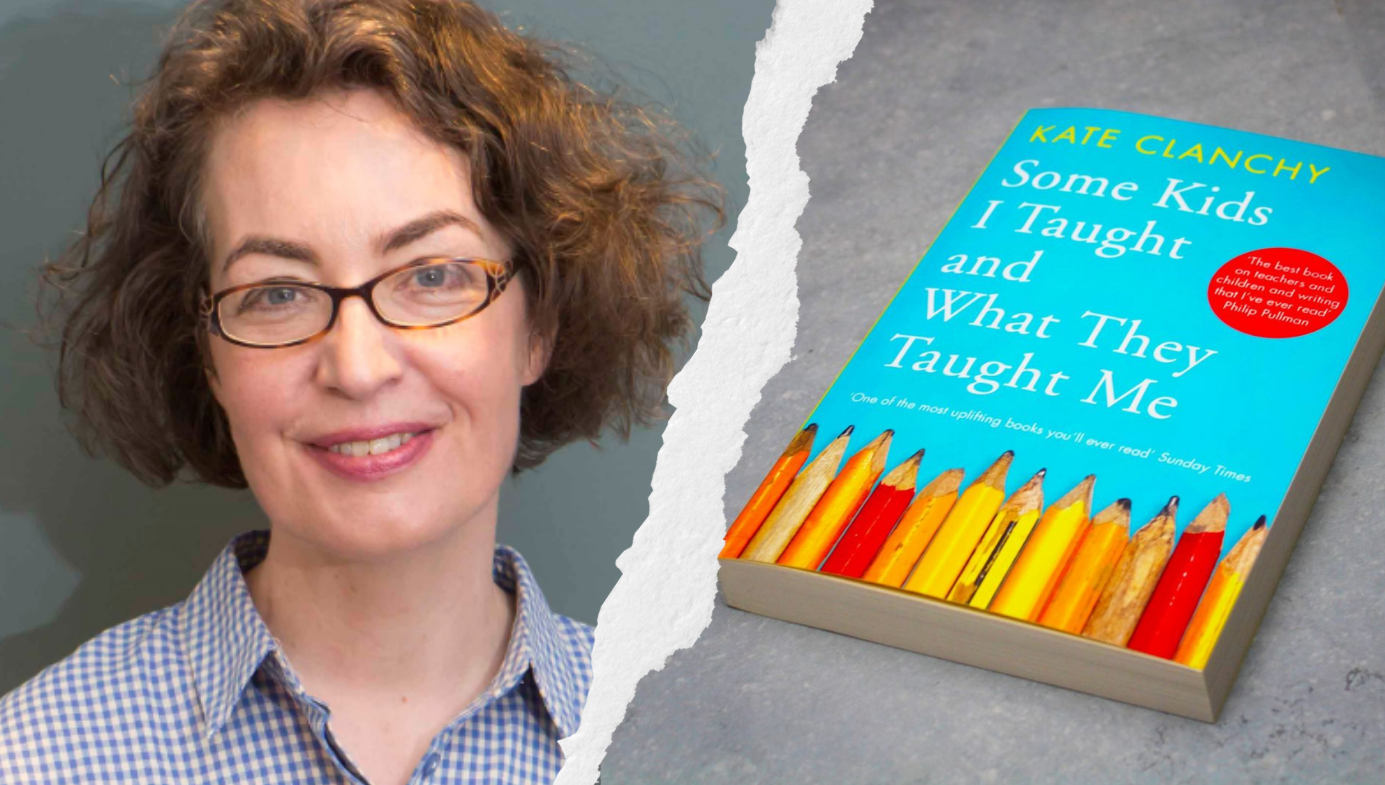

In 2020, mid-COVID, the UK's Orwell book prize was awarded to the British writer Kate Clanchy for her memoir, Some Kids I Taught and What They Taught Me. It was based on Clanchy’s experience of teaching in state schools, and among her pupils had been many students of colour and autistic children. The Orwell Prize jury found the book to be “moving, funny and full of life,” offering “sparkling insights” into the teaching world in which she had worked.

Shortly after the award, users on Twitter and Goodreads accused the writer of “racial stereotyping” and “ableism.” Clanchy had described a black child as having “chocolate coloured skin,” and “almond-shaped eyes,” and two autistic children as “unselfconsciously odd” and “jarring company” which, if in their company for a week, she would find irritating, but for an hour, “I like them very much.” At another point, she described a student as “so small and square and Afghan with his big nose and premature moustache” and referred to another as “African Jonathon.”

In response to the initial wave of social media criticism, Clanchy first said she had been quoted out of context. However, when the controversy was revived in August this year, she confessed that her critics were “right to blame me, and I blame myself … I am not a good person, not a pure person, not a patient person, I am nobody’s saviour.” Picador joined in saying, “We want to apologise profoundly for the hurt we have caused, the emotional anguish experienced by many of you who took the time to engage with the text.” Both author and publisher will return to the text for a rewrite.

The Orwell Foundation, meanwhile, issued a painstakingly cautious statement, which delicately distanced itself from the decision of its own panel of judges. It stopped short of denouncing Clanchy but didn't defend her either:

The Orwell Foundation acknowledges the concerns and hurt expressed about Kate Clanchy’s memoir, Some Kids I Taught and What They Taught Me (Picador, 2019), winner of The Orwell Prize for Political Writing 2020. The Foundation understands the importance of language and encourages open and careful debate about all the work which comes through our prizes. Everyone should be able to engage in these discussions, on any platform, without fear of abuse.

The Orwell Prizes are awarded by a panel of independent judges, appointed each year by the Foundation, who make their own decisions as to the awards in each category. The Foundation does not comment on individual judging panel decisions.

What's striking about this episode is how it is at once so petty and so serious. Petty, because Clanchy's offending comments were innocent—this was a memoir, and Clanchy’s honestly recorded reactions betray no contempt or malice, and could not reasonably be confused with bigotry, even the most broadly defined sense. This is someone who had spent 30 years of her life teaching migrant and disabled children. When, in June this year, Clanchy received an MBE for her work, the Poetry Society (of which she is a member) said that over nine years in her last school, she had:

...nurtured creative talent at the school, whose pupils come from all over the world and where more than 30 languages are spoken … the pupils in Kate’s ‘Very Quiet Foreign Girls’ poetry group, many of whom arrived in the UK as refugees, have also created a radio programme, which was nominated for The Poetry Society’s Ted Hughes Award in 2015. … the best of the pupils’ poetry [was] published in a new anthology, England: Poems from a School, on 14 June. The poems create a portrayal of England as it is experienced by young migrants, and features moving personal stories from the pupils.

In her humiliation, Clanchy sought refuge in radical self-criticism, but both the society and the committees who award MBEs—usually given for civically virtuous activity—clearly thought that she is a good person.

Her critics included Chimene Suleyman, Monisha Rajesh, and Sunny Singh—young writers preoccupied (as all young writers are) with self-promotion. And one way of promoting oneself in the current climate is to denounce racism in white writers on social media. Racism is much-diminished in British public life compared to previous decades, and it is much less evident in highbrow literature than in almost any other sphere of British life. Yet even by the ruthless standards of the racial denunciation genre, selecting Clanchy of all people to be racist of the week was plainly nuts. To offer her unguarded admission that lengthy sessions with autistic children could irritate her and her innocuous observation that one of the kids she taught had almond-shaped eyes as evidence of bigotry is a profoundly dubious means of self-advertisement.

Clanchy's record of helping disabled and migrant children is not a secret. Was it not consulted? If consulted, shouldn't Suleyman, Singh, Rajesh, and others have at least balanced their vitriolic remarks with an acknowledgement of that work? Clanchy's wretched claim that she is “nobody's saviour” suggests that even she was embarrassed to mention her record in her own defence, perhaps anticipating that an accusation of racist condescension was about to be added to her existing litany of sin.

Suleyman thanked Picador for their apology but wanted to know “why content of this nature even reached bookshelves, schools, and was celebrated by prestigious awards.” She told the Guardian that:

The unsettling escalation we have witnessed is not simply down to one author’s book, but an alarming and distressing reaction from our publishing peers when engaged with on this. I would, similarly, like to ask publishing how they will be addressing authors and peers who have contributed towards the heinous racism and ongoing harassment against writers such as myself, Monisha Rajesh, and Sunny Singh for speaking out on the matter.

It would have been nice to know the detail of this heinous racism, which could—if truly heinous—have been the subject of police enquiry, but detail hasn’t been forthcoming. Rajesh, meanwhile, told the BBC that she didn't believe the book could be improved by rewriting, “given that it is riddled with racist and ableist tropes throughout,” and included language “rooted in eugenics and phrenology.”

The serious part of this is the all-out attack pursued against Clanchy on social media for the most minor of slights. This behaviour is now baked into the operation of social media, which provides a painless method of inflicting great reputational pain. More, it has persuaded those who have done nothing wrong that the only way to stop the attacks is to deliver the most abject apologies for something that requires no apology at all. It’s easy to sympathise with Kate Clanchy: she just wanted it all to go away. Picador, like many publishers, also panicked and covered its corporate head with ashes in the hope that its tormentors would leave it alone.

This dance of outrage and repentance has become dismayingly familiar. And each time the dancers take the floor, some more of the commitment to uphold freedom of speech and artistic expression dies a little. What Picador and Clanchy were offering was less an apology than a routine with a well-established series of steps. An earlier example: in June 2019, a British man in his late-50s named Brian Leach was fired from his job as a greeter at Asda in West Yorkshire for a “gross breach of company policy.” Leach had sent a video clip to a colleague on Facebook in which the Scots comedian Billy Connolly mocked religion, especially Christianity and Islam. The clip is scathing and full of obscenities, but it is also very funny (at least, if you aren’t a devout Christian or Muslim).

For this, he apologised, but was not reinstated. Leach’s job is low paid, but he needed it after he was left disabled by an accident. Luckily, following intervention by the National Secular Society, he was reemployed. Stephen Evans, the secretary of the Society, said that “the case raises broader concerns about the extent to which employers can legitimately restrict their employees’ freedom of expression on social media.”

The concern is that employers are behaving like this everywhere, shamefully unprepared to defend the values of a society, the legal framework of which affords them the freedom to make profits. Admittedly, some establishment figures do uphold Millian free speech standards: Sir Alan Moses, former chairman of the Independent Press Standards Organisation, said on his retirement, “What we have to acknowledge is that, in striking the right balance in this country, there is no right not to be offended.” But for the most part, the commercial, academic, and literary landscapes are fraught with fearful caution.

Suleyman, Janesh, and Singh have claimed a general right to be spared offence—not merely on their own behalves, but on behalf of all people of colour. And upon what basis? How can they possibly know if Clanchy’s mild and generally affectionate comments strike all men and women of colour as nothing more than racial insults and the savage mockery of autistic children? They are simply writers and commentators speaking for themselves and pursuing their own grand ideas and narratives at the expense of another's reputation.

It’s the sheer volume and vehemence of sweeping claims like these that demand we take them seriously, even though they are patently unserious. The high tide of white supremacy occurred in the European colonies occupied from the 18th to the early 20th century. In the United States, racism still casts a particularly poignant shadow since the crime was exacerbated by the concomitant proclamation that “all men are created equal”—an indignity for slaves on top of the physical cruelties they suffered. Liberation was followed by a century and a half in which, most obviously in the American South, an effective apartheid ruled, more than a little of that slopped into the North, and some remains.

In Britain, by contrast, while racism of course persists, it is really only on the margins of society, pursued by tiny far-Right and fascist parties, not one of which has succeeded in winning more than a tiny share of the vote at elections. When then-leader of the anti-European Union UKIP party, Gerard Batten, hired the far-Right activist Tommy Robinson as an advisor, he was undermined by one of his predecessors, Nigel Farage, who resigned in protest. All UKIP MEPs subsequently lost their seats in the EU parliament. Seeking re-election in 2019, Batten was prevented from standing by the UKIP's executive committee, who judged he had brought the party into disrepute.

Societies, if well and liberally governed, can deepen acceptance of religious and ethnic differences, but only so long as minorities and those among the elites who claim to represent them make this their aim and their practice. A lasting diminution of racism rises from millions of everyday interactions—at work, at leisure, in schools and colleges, in religion, in cultural pursuits, in political activity and debate. Racism and prejudice will never entirely disappear, but it can be diminished and held in contempt by the large majority.

This, of course, can change under circumstantial duress. Hard times, high unemployment, low or negative growth, and stagnant or declining wages could yet turn different communities against each other, especially if there was little contact before. But to fall into such a period while an inflammatory hostility to whites is being promoted in the name of equality and anti-racism would be disastrous. Those who hunt for racism in the work of writers like Kate Clanchy—a soft target, as in most such attacks—don’t appear to care about, and may even celebrate, the racial antagonism their pious agitprop inflames.

The identity mavens who attacked Clanchy continue to grow in power and scope. Yet their grasp is, in one sense, quite fragile. The legitimacy of the reputational terrorism they practice depends upon the capitulation and expressed remorse of their targets. Whether there was actually any racist, homophobic, or otherwise bigoted intent is secondary. The fear of being branded with one of the most deadly contemporary sins has generally ensured a pusillanimous collapse by corporations, institutions, and individuals. English middle- and upper-middle-class guilt, coupled with a horror of being shunned as prejudiced, weakens the spine. An organisation named after George Orwell should have offered a fiercer defence of one of its hitherto-celebrated prizewinners.

This needn’t continue. A scholar has pointed the way out. In a short 2011 monograph entitled That’s Offensive! Criticism, Identity, Respect, the Professor of Intellectual History at Cambridge, Stefan Collini, writes:

Clearly, there can be forms of misrepresentation which, especially in already inflamed circumstances, may be the direct cause of harm to those so misrepresented and there may be a reasonable case for legal or other intervention. But this is evidently different from cases where the spokespersons for a particular group simply claim that a representation is so much a stereotype that it is offensive.

Apart from anything else, these protests tend to underestimate the critical discrimination of audiences where such representations are involved. After all, stereotypes and caricatures have a perfectly legitimate and well-understood role in various kinds of writing and other arts: not all representations attempt to be, or should attempt to be, fully rounded portraits. But readers and audiences know this, and they are rarely lulled by a stereotype into mistaking it for the reality.

This is an argument for engagement in rational debate with an open mind as a means of defeating the obsessive activities of the guilt-finder generals. Collini again:

It means treating other people as we wish to be treated ourselves in this matter—namely, as potentially capable of understanding the grounds for any action or statement that concerns us. But to so treat them means that, where reasons and evidence are concerned, they cannot be thought of as primarily defined by being members of the “Muslim community” or “Black community” or “gay community” or “cycling community” or any other “community.” In these familiar phrases, “community” is slackly used not just to indicate a group of people who are assumed to have some property in common, but also to prejudge their interests they are assumed to have at stake in the question under discussion.

Prejudging interests in this way is hugely destructive of a wider community—one in which people of all colours live and work in proximity to each other, and at times cooperate, find friendship, attraction, and loving partnerships. A society need not always be “at ease with itself” (which former prime minister, John Major, once declared was the goal of his premiership). But it needs civic engagement across every kind of line, especially those of ethnicity, to sustain it, and to determine that debate, no matter how heated, remains open and productive of understanding.