Middle East

Revisiting Kirkpatrick

Constructive relationships with dictatorships will be key to protecting US interests without direct military involvements.

The concept of freedom has been deeply embedded in the American tradition since the country’s founding. Not only did classical liberal values profoundly shape governance at home, but they also manifested themselves in foreign policy as the United States emerged as the world’s predominant power. In 1917, President Woodrow Wilson announced the American entry into World War I as an effort to create “a world safe for democracy.” If this liberal internationalism faltered during the isolationism of the interwar period, it was reignited by the outbreak of an even deadlier conflict 20 years later. Washington was convinced that the only way to prevent another breakdown of order was to remake the world in its own image. In the decades following World War II, American presidents poured considerable resources into creating and upholding a “Liberal International Order,” through which Washington would act as the global guarantor of democratic capitalism.

However, a commitment to spreading democracy and advancing human rights in Europe and Japan did not stop American policymakers from backing tyrants throughout the world during the postwar era. US administrations recognized that a successful containment strategy against the Soviet Union and Communist China would require unsavory alliances with anti-Communist dictators, like Nicaragua’s Anastasio Somoza and Taiwan’s Chiang Kai-shek. Fears of “falling dominoes” and nuclear war often sidelined anti-authoritarian instincts during the Cold War.

Some US officials were uncomfortable with what they considered to be a duplicitous policy. How could the United States claim to be the leader of the “free world” while empowering tyrants elsewhere? How could Americans lecture the Soviet Union on its behavior in Eastern Europe while turning a blind eye to the atrocities of right-wing dictatorships? In the late 1970s, the Carter administration sought to rectify this double-standard with a strict human rights policy, which made economic and military aid to autocratic regimes conditional on human rights progress and liberal reforms.

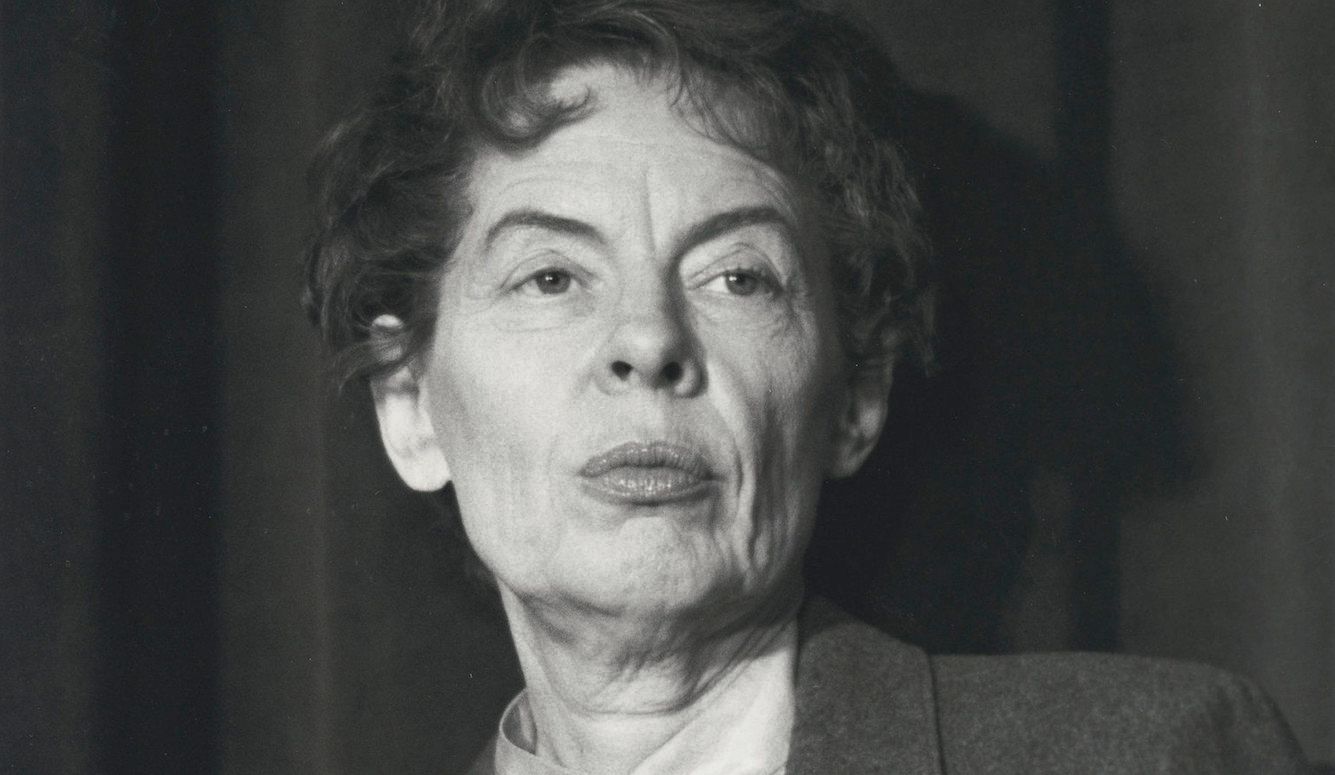

This approach was soon met with criticism. In 1979, political scientist Jeane Kirkpatrick published a widely discussed essay in Commentary entitled “Dictatorships and Double Standards,” in which she lambasted the Carter administration for entertaining a double standard of its own: accepting the status quo in Communist regimes while taking a hard stance against authoritarian allies. Kirkpatrick criticized Carter for abandoning pro-US dictators in Iran and Nicaragua and allowing revolutionary groups to rise to power. The problem was not just that the upheavals in 1979 could benefit the Soviet Union, which appeared to be on a roll in the 1970s under Leonid Brezhnev’s iron grip. According to Kirkpatrick, the Islamic Revolutionaries and Marxist Sandinistas that came to power in Iran and Nicaragua, respectively, were “totalitarian” groups that were even more oppressive than the tyrants they had replaced. US support for right-wing dictatorships was thus not just strategically justified—it was also morally justified, since traditional autocracies were essentially the lesser of two evils compared to their totalitarian opponents.

This distinction between authoritarianism and totalitarianism was a cornerstone of Kirkpatrick's argument. Traditional authoritarian leaders are oppressive and constrain political participation, but “do not disturb the habitual rhythms of work and leisure, habitual places of residence, habitual patterns of family and personal relations” like totalitarian regimes do. Authoritarian states enforce order, whereas totalitarian states enforce order and belief. To Kirkpatrick, this distinction gave authoritarian states some chance of evolving into democracies down the road, whereas radical Communist and Islamist dictatorships grounded in revolutionary ideology would not liberalize voluntarily.

“Dictatorships and Double Standards” resonated with many neoconservatives who had become disillusioned with Carter’s passivity towards the Soviet Union as well as with Nixon’s concessions to Moscow under “détente.” However, not all neoconservatives agreed with Kirkpatrick’s implications. Paul Wolfowitz, for instance, felt that the goal of US policy should not just be containing the Soviet Union, but also spreading democracy worldwide, whereas Kirkpatrick represented the “realist” neoconservative camp. Kirkpatrick never advocated abandoning the cause of freedom altogether, but she warned that the imposition of liberalization risked inadvertently paving the way for revolutionary agents in the Third World. Democratization, she argued, should not be expected to happen overnight through forceful policies that alienate “friendly” autocrats, but rather through a gradual expansion of political liberties.

Kirkpatrick’s argument proved to be prescient on many accounts. In East Asia, North Korea, Vietnam, Laos, and China remain one party dictatorships, whereas South Korea, Taiwan, Indonesia, and the Philippines became democracies as the Cold War drew to a close. Similarly, many Latin American military dictatorships, despite grotesque human rights records, evolved into democracies of some form in the late 20th century. Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet is often cited by Kirkpatrick’s supporters as an example of an authoritarian who enacted liberal reforms and eventually stepped down. Meanwhile, Cuba continues to suffer under Communist domination, and Venezuela has grown more authoritarian under Chavez and Maduro since 1999.

The democratization of the former Soviet Bloc and integration of Central and Eastern Europe into the European Union challenges Kirkpatrick’s claim that totalitarian states could not become politically liberal societies. Nevertheless, Kirkpatrick could still maintain that, although liberalization in totalitarian countries may be possible, it is less likely than in authoritarian ones. Behind the Iron Curtain, external actors like the Western democracies, the Catholic Church, and eventually Mikhail Gorbachev had a heavy hand in dismantling the Communist dictatorships and enabling transition to democracy. Moreover, the fact that many of these countries had a long history of liberal traditions validates Kirkpatrick’s point that “decades, if not centuries, are normally required for people to acquire the necessary disciplines and habits” for genuine democracy to take root. Kirkpatrick could also allude to the difference between collapse and reform, the former being primarily the case in the Soviet Union’s dominion. Gorbachev, after all, had initially set out to save Communism, not bring about its downfall.

Some foreign policy idealists take issue with Kirkpatrick’s assertion that “architects of contemporary US foreign policy have little idea of how to bring about the liberalization of an autocracy.” They point out that the Reagan administration’s push for reforms in the Philippines, South Korea, Taiwan, and Chile in the mid-1980s enabled democratic transitions while also preventing radicals from coming to power. Moreover, while it is true that both the Sandinistas and Islamic Revolutionaries exploited Carter’s human rights policy to expand their influence, one might also argue that unconditional support for autocrats by previous US administrations was what led to the revolutions in the first place. Nor was it always the case that anti-Communists were the lesser of two evils and “didn’t produce refugees”—the US-backed military dictatorships in Central America may have matured into more representative forms of government, but they were responsible for the majority of human rights abuses compared to the leftist guerrillas during the civil wars.

However, while Kirkpatrick’s suspicion towards immediate democratic transitions in the 1980s may be partially discredited, a long view of the events leading up to those transformations validates her underlying premise. Patience with the authoritarian regimes like South Korea and Taiwan over the preceding four decades, despite their numerous atrocities, was ultimately prudent. Not only did this strategy allow the United States to prioritize the most immediate threats in the region, but it also facilitated its East Asian allies’ transition to democracy in a sustainable manner. Pressing too heavily for liberal reforms during the height of the Cold War would have risked destabilizing Seoul and Taipei and making them vulnerable to subversion by the surrounding Communist powers, destroying any prospect of freedom. In the case of Chile, Reagan’s decision to restore diplomatic ties with Pinochet allowed the administration to use its leverage over the dictator to gradually prod the country back on the path of democracy. Indeed, sometimes a more hard-nosed policy may have backfired, as it did in Iran and Nicaragua. But constructive relationships with authoritarian regimes need not be analogous to the blank checks granted by Nixon and Kissinger, both of whom also came in for criticism by Kirkpatrick.

The Kirkpatrick Doctrine was not just insightful during the Cold War. It also consists of several tenets that are applicable to modern day foreign policy dilemmas:

- The best way to promote democracy is by prioritizing immediate threats while prodding liberalization over the long term.

- US administrations should not overestimate the prospect of democratization in authoritarian states, as opposition groups may not necessarily be pro-democracy.

- Not all authoritarian states are equal, and US policymakers should distinguish between them.

- Alliances with authoritarian regimes can advance US interests, and often (albeit sometimes in unintended or unexpected ways) US values.

These guidelines offer a useful template for the Greater Middle East, which has been the primary focus of the United States in the post-Cold War era. Are autocracies useful allies in the war on terror, or do they fuel extremism with repressive crackdowns? Should the US support Islamist organizations such as the Muslim Brotherhood, or do these parties see democracy as a means to an end? Why should Washington back some authoritarian regimes, such as Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Egypt, while taking a harder line on the Islamic Republic of Iran? The Kirkpatrick Doctrine can help answer these complex questions.

The failure of the Freedom Agenda

The attacks of September 11th, 2001 prompted the United States to reconsider its strategy of favoring the forces of authoritarianism in the Middle East. President Bush’s neoconservative advisors, most notably Paul Wolfowitz, interpreted Islamic radicalism as a symptom of the oppressive regimes throughout the Arab world. The degree to which this neoconservative worldview is culpable for the 2003 invasion of Iraq remains a point of debate among scholars. However, there was a broad bipartisan consensus in Washington that the overthrow of Saddam Hussein and installation of democracy in Baghdad would trigger a wave of democracy throughout the region and “drain the swamp” from which anti-American terrorism emerges. Similarly, in Afghanistan, the US did not just focus on a narrow campaign against Al-Qaeda, but pursued a broader war against the Taliban and an ambitious nation-building project. The Bush administration maintained strategic ties with autocratic regimes such as Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Egypt, but aggressively pushed for reforms in these societies between 2003 and 2006 through programs such as the Middle East Partnership Initiative.

Though President Obama promised a departure from the approach of his predecessor when he took office, in reality he continued Bush’s idealism in many ways. Obama initially vacillated in his response to the Arab Spring uprisings, but for the most part followed through on his promise to initiate a “new beginning” with the Islamic World. The administration convinced Egyptian strongman Hosni Mubarak not to crack down on protestors and eventually step down from power, and even established ties (albeit cautiously) with the new Muslim Brotherhood president Mohamed Morsi. Optimism for the Arab Spring also informed Obama’s decision to help topple Gaddafi in Libya and arm some Syrian rebel groups.

The failure of Bush and Obama’s attempts to extend “liberal hegemony” to the Islamic World soon became apparent. The sight of elections taking place in Iraq as well as Bush’s pleas for reform helped undermine authoritarianism throughout the region. However, it was not Jeffersonian democrats who emerged victorious in the new municipal and legislative elections, but Islamists who were much less favorable towards American national security goals, and in many cases just as hostile towards democracy as the authoritarians they contested. One could only recall Kirkpatrick’s warnings after Hamas assumed dictatorial power through the 2006 Palestinian elections advocated by Bush and Condoleezza Rice. In Egypt, President Morsi initially enjoyed popular support among Egyptians, but he slowly drifted towards authoritarian rule and gravitated towards Hamas. Discontent with the Brotherhood’s failure to build an inclusive political process eventually culminated in the 2013 military coup, which brought General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi to power in Cairo. Although many optimists for the Arab Spring were understandably left dejected by the end of Egypt’s brief experiment with democracy and the new regime’s crackdowns, the ousting of Morsi was widely supported among Egyptians, and was even celebrated by some of his former supporters. Additionally, the country’s economic growth and improved conditions for religious minorities and women under Sisi overshadow some of the more sinister aspects of his rule. Meanwhile, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s consolidation of power in Ankara shattered hope in the West of Turkey becoming a model democracy for the rest of the Middle East, and is yet another cautionary tale of what happens when Islamists come to power.

Despite these trends, some commentators insist that the region’s most pressing issues, such as the rise of Sunni radicalism, stem from its dearth of representative institutions. The idealists cling to Tunisia’s successful transition during the Arab Spring to justify a democracy promotion agenda. If Bush and Obama are criticized, it is for the alleged half-heartedness and inconsistency of their reform efforts, not for their underlying assumptions. Had the United States committed itself more to nation-building in Iraq or protecting Morsi in Egypt, the argument goes, perhaps the outcome could have been different.

Indeed, it is too simplistic to portray all Islamists, including the various branches of the Muslim Brotherhood, monolithically. But by the same token, one should also not insist that all Islamists are democrats because of the moderation of the Islamist Ennahda Party in Tunisia. The case of Tunisia during the Arab Spring is anomalous for several reasons, including major cultural differences between the country and other Middle Eastern and North African states. Ennahda Party leaders also reject the notion that they are the “Tunisian branch” of the Muslim Brotherhood due to several political and ideological differences with the organization. Another key reason for the successful transition to democracy in Tunis was that Ennahda worked within a broader coalition of secular parties since becoming legalized in 2011.

The Tunisian case challenges another underlying assumption of the Carter-esque critique of Middle Eastern autocracies: that the oppressive regimes in the Arab world are the root cause of Islamic extremism. It may seem intuitive that authoritarians’ excesses create fertile breeding grounds for radicalization, but it is too simplistic to ascribe transnational jihadism to the persistence of dictatorships in the region. As the scholar F. Gregory Gause has pointed out, there is no convincing empirical relationship between regime type and terrorism—members of terrorist organizations come from both democratic and non-democratic states, and commit attacks against both types of states. Certainly, draconian anti-extremism policies are often counterproductive, but there is little reason to believe that the emergence of democratic states would prevent terrorism from emerging. Tunisia’s successful transition to democracy during the Arab Spring is laudable, but this has not prevented Tunisians from featuring disproportionately in jihadist organizations in Iraq and Syria since 2011. Egypt, on the other hand, has exported merely one 10th of that number despite being more authoritarian.

Neither Bush's Freedom Agenda nor Obama's attempts to nurture the Arab Spring led to more democracy and less terrorism—instead, they destabilized major portions of the Middle East and North Africa and fueled the rise of more Islamist extremists groups, while costing the American people trillions of dollars.

An intra-regional Cold War

Another egregious error of the idealist approach to the Greater Middle East in the last two decades has been to strain relationships with key authoritarian allies. If the Bush administration’s decision to invade Iraq and its proclamation of a “Freedom Agenda” vexed the Gulf monarchies, then President Obama’s willingness to establish ties with the Muslim Brotherhood and engage Iran in talks for a nuclear agreement risked jeopardizing the relationship entirely. One may ask why the US should support these states, and other allies like Egypt and Jordan, while countering Iran. Kirkpatrick’s distinction between traditional autocracies and revolutionary dictatorships can illustrate how these various regimes differ in their regional ambitions.

The “status-quo” rulers of Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Kuwait, Oman, and Bahrain are repressive, and some may take extreme measures to ensure their security, but none wish to fundamentally alter the regional landscape. President Mubarak maintained stable relations with Israel during this 30-year reign, whereas Morsi’s tilt towards Hamas threatened this peace. Sisi restored relations between Israel and Egypt, and has also played a constructive role in fighting extremism in the Sinai. The Gulf monarchies (with the possible exception of Qatar) seek to prevent a political reorientation of the Middle East by countering radical Islamism and containing Iran’s use of proxies. The Abraham Accords peace deals between the Gulf countries and Israel, facilitated by President Trump (and encouraged by Saudi Arabia), demonstrates these states' willingness to cooperate to address the region's challenges. This preservation of the status-quo in the Persian Gulf is critical to preventing large-scale conflicts, defeating terrorism, and maintaining the uninterrupted flow of oil for the global economy.

While Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states once had a problematic connection with Sunni jihadism, the Saudis have made significant progress in distancing themselves from their past history of exporting hardline Salafism and financially backing Islamist terror organizations. 9/11 and a wave of attacks against the Saudi Kingdom in 2003 prompted the Royal Family to crack down on private fundraising networks for Sunni extremists, and take swift action against Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula. The leading role shouldered by Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Bahrain in US-led joint operations against the Islamic State was also a positive sign in terms of these countries’ regional outlooks. Additionally, repression against hardline religious clerics has greatly intensified under Saudi crown prince Mohammed Bin Salman’s ambitious campaign to modernize the Kingdom. Still, problems remain, including the arrests of liberal human rights activists and ongoing conflict in Yemen. Nonetheless, the overall direction of Saudi Arabia under MBS is encouraging. Moreover, critics of the Saudi and UAE intervention in Yemen often understate Iran’s involvement in the conflict and the genuine security threat the Houthis pose towards the Kingdom.

These status-quo regimes are to be contrasted with revisionist powers such as Iran, which seek to overturn the US-led order in the region through regional proxies such as Hezbollah in Lebanon, Shiite militias in Iraq, and the Houthi rebels in Yemen. Whereas most Gulf states’ connection to Sunni jihadism primarily consists of private actors outside the government (and has significantly waned since 2003), Iran’s backing of terrorist organizations is blatantly state-sponsored. The Islamic Republic has not only propped up Shiite extremists, but has also backed Sunni jihadist organizations such as Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad, and even maintains a secretive relationship with Al-Qaeda. Moreover, Tehran’s extensive influence in Iraq and Syria alienated Sunnis and created a fertile breeding ground for the sectarian narrative of IS and its precursor, Al-Qaeda in Iraq.

Iran’s behavior under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action demonstrates why rapprochement is not a likely solution. Instead of moderating its behavior in the region as expected, Iran exploited the lifting of sanctions to escalate its involvement in Syria, pour more money into its regional proxies, and build enhanced ballistic missile and drone capabilities. As noted by former Iranian prisoner Xiyue Wang, Iran derives its legitimacy domestically by opposing the United States abroad. If the Biden administration is to pursue a “new Iran Deal,” it must take into account these revisionist ambitions and limit Tehran’s avenues of regional expansion, while consulting Gulf allies throughout the negotiation process. Biden should also pick up where Trump left off in terms of building a geopolitical front against the Islamic Republic.

Qatar and Turkey have also shown concerning signs in recent years, partly because Islamism has influenced their foreign policies. Both countries have backed hardline jihadist groups such Jabhat Al-Nusra, and Qatar has maintained close ties with Hamas. Qatar’s participation (albeit halfhearted) in coalition airstrikes against IS in 2014, as well the recent reconciliation between Doha and other Gulf states shows that the country has not drifted completely from the US-led order. Nonetheless, Washington should still keep a watchful eye over Qatar’s support for transnational Islamism. Ankara’s drift from the West has largely been driven by concerns over Washington’s support for the People’s Protection Unit (YPG), the Syrian Branch of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), a US- and Turkish-designated terrorist organization. Nonetheless, while this tension features a geopolitical dimension, American policymakers should recognize that Erdogan’s increasingly Islamist foreign policy will likely pose problems in the future.

None of this excuses the foreign policy errors of Washington or its status-quo allies in the Middle East. Nor should dictators be given a blank check to repress their population in the name of fighting Islamism. However, isolating autocratic rulers will achieve neither stability nor democracy. As David Ignatius has argued, weapons bans on Sisi could create a “lose-lose” situation that yields “no progress on human rights and diminished security for both countries.” Stringent human rights policies can also drive allies into the hands of China or Russia, open opportunities for Iranian expansion, and risk empowering domestic opponents of pro-American autocracies such as radical Islamists or even outright jihadists. While Biden should take steps to criticize allies when events—such as the killing of journalist Jamal Khashoggi and reckless intervention in Yemen—demand it, the administration must not lose sight of the broader picture by setting unrealistic and counterproductive expectations for human rights progress. A better approach is to heed Kirkpatrick’s advice to maintain close ties with authoritarian allies while encouraging liberalization moderately. Such a policy will not only allow the US to achieve its geopolitical objectives of containing Iran and fighting extremism, but can also lay the groundwork for institutions that are crucial for lasting democracy, and empower secular political parties to eventually contend with Islamists.

Conclusion

The foreign policy of the United States would not be complete without an underlying moral purpose. Indeed, a major outcome of the Cold War was a global recognition of democratic governments and human rights norms, even if Americans themselves may have fallen short of these ideals at times. To this day, the Liberal International Order remains a remarkable success by Washington, and many democracies in Europe, East Asia, and Latin America continue to flourish.

However, this Order was not advanced through shortsighted human rights castigations or overzealous democracy promotion agendas. It was built over decades of prudence and careful prioritization of American interests. Many of the freedom-loving countries across the world today were once perpetrators of brutal repression. Yet as Kirkpatrick predicted, patience with authoritarian allies paid numerous dividends throughout the Cold War—not only in terms of defeating the Soviet Union, but also in advancing the cause of freedom globally.

Needless to say, applying the Kirkpatrick Doctrine in the 21st century will have its share of successes and failures, just as it did during the Cold War. But at a time in which Americans have grown distasteful of long-term military engagements, Washington cannot be picky and choosy about how authoritarian allies behave. Constructive relationships with dictatorships will be key to protecting US interests without direct military involvements. And skeptics need not worry that such a policy will be morally bankrupt. Just as the fall of Soviet Communism coincided with the spread of democracy worldwide, so too can the fall of Sunni jihadism and Iranian expansionism pave the way for more just and prosperous societies throughout the Greater Middle East.