Entertainment

Life as a Stand-Up Comic Can Be Brutal. ‘Safe Space’ Call-out Culture Is Making it Unbearable

“Cancel culture” has become a trendy term in recent years. But public shaming has always existed. It’s a social tool, and like all tools can be used for good or ill.

Most of you have never heard of Chanty Marostica. But in 2019, they were considered a rising star in the Canadian comedy industry. Originally based out of Winnipeg, Marostica is transgender and non-binary, and was hailed as a leader of the growing diversity movement in Canadian comedy. They’d won some of Canada’s most prestigious Comedy Awards: SiriusXM’s Top Comic in 2018, as well as the Canadian Comedy Awards’ 2018 Best Breakout Artist and 2019 Best Album. In 2018, that album, The Chanty Show, was also nominated for a Juno Award (our Canadian version of a Grammy). On the basis of these credentials, one might imagine Marostica to be one of the funniest people in Canada.

Search Marostica’s name on the web, and you’ll find plenty of information about these accolades, as well as glowing accounts of the comedian’s role as an advocate for queer comics and safe spaces in stand-up comedy. What you will not find is any indication that Marostica has (or rather had) anything in the way of a real fan base outside of their immediate circle of progressive friends and supporters. Nor will you find any mention of Marostica’s role as a gatekeeper in queer comedy and a callout king in Canadian stand-up, as illustrated by the case of Matt Billon, a stand-up veteran and runner-up for SiriusXM’s Top Comic in 2015.

In February 2019, Billon was on a show with Marostica at the Hubcap Comedy Festival in Moncton, New Brunswick. Billon was late, his first flight to New Brunswick having been delayed and turned back due to weather. He arrived at the venue halfway through his first show (of three) that night, shortly before he was to perform. He ran into Marostica before taking the stage, and made a point of congratulating them on their recent SiriusXM win.

During his headliner set, Billon made a lighthearted joke about trans athletes and how their inclusion was going to make women’s sports more exciting—a joke Billon had told plenty of times before, including in front of (appreciative) queer audiences. When he returned to the comics’ table backstage, Marostica had already departed, leaving a note informing Billon that they (i.e., Marostica) were trans and insulting him. By the time he’d finished his second set, Billon’s Facebook page was flooded with accusations of transphobia, following on Marostica’s social-media call out of Billon as a bigot.

He repeatedly tried to reach out to Marostica, offering to have a private conversation, or even a public discussion. He also tried to apologize for hurting their feelings. But as is usually the case in such controversies, these gestures only made the public attacks worse.

Billon received private messages expressing support—including from members of the queer community in Winnipeg, Marostica’s home town—telling him that this kind of behaviour was typical of Marostica, and that he had done nothing wrong. In public, however, the silence was deafening. According to Billon, none of his fellow comedians stood up to defend his character. It was the cowardice of his friends and colleagues that hurt most, he later told me.

Back at home in Vancouver, a local producer responded to the controversy by cancelling a free seminar that Billon was offering to new comics—allegedly because of pressure from others. That producer was Suzanne Ross, better known as Suzy Rawsome, a comedian who presides over Vancouver’s in-group progressive stand-up clique, and who figures prominently in many of the stories that follow.

Of course, there are worse professional setbacks than having one’s free teaching seminar cancelled: It’s not as if Billon were out any money. But the real point of the cancellation wasn’t the event itself, but the signal it sent to everyone in the tightly networked Vancouver comedy community: Billon now carried the progressive mark of Cain.

On account of his 2015 runner-up finish in the SiriusXM Top Comic competition, Billon was owed a gala performance at Just For Laughs (JFL), a large government-funded Montreal festival that’s become an important make-or-break institution for Canadian comics. He was unable to take the slot in 2016 due to medical treatment, but the booker for JFL kept promising that there would be a rescheduled date. Somehow, that date never seemed to arrive. Billon later was told that the same booker had been following along with Marostica’s social-media mob, clicking “like” on comments denigrating him. In a tiny subculture such as Canadian stand-up comedy, these are the digital breadcrumb trails by which one can track his or her own cancellation.

It would be another eight months before the other shoe dropped. In October 2019, Louis C.K. performed for five nights at Yuk Yuk’s comedy club in Toronto—a development that the progressive comedy scene viewed with horror. Unlike many of the more obscure comedians discussed in this essay, C.K. was known to have done some genuinely awful things: In 2017, he admitted to masturbating in front of female comedy colleagues. And the Canadian arts press was furious that C.K. not only was performing in Canada, but that his shows were sold-out blockbusters full of wildly appreciative fans. Following C.K.’s performances, Marostica wrote a (later-deleted) Facebook post, which appeared under a photo of C.K. and a Canadian club owner:

Jesus Christ. Y’all 1000% give zero shits about the women you employ. CONGRATS on a fun week … You will sign so many women in the future who won’t say it to save their job, but it hurts every single time we are told that the abuse we incur in this world is acceptable. Every time you book an abuser, it stings … booking Jeremy Piven and Louis CK for exactly THIS. The backlash, the negative press, the shock. It’s gross, unsurprising, lazy and archaic. I was assigned female at birth. I am allowed to have an opinion about your club purposely hiring people who abuse us.

But this accusation of abuse backfired badly, as two commenters took the opportunity to air their own accusations against Marostica:

[Comedy Club Employee]: When speaking about abusers, people who live in glass houses shouldn’t throw stones. Let’s open up the discussion to everyone in the community that you sexually or physically abused. So good day to you sir!

[Female Comic]: I can confirm [Comedy Club Employee’s] accusations with knowledge of 4 more people who experienced abuse like I did and worse. Most folks know about their [Marostica’s] behaviour as a predator and gatekeeper. No one is willing to speak out or defend the young queer people who are subject to their violence … I’m currently being threatened to stay quiet. Trying to figure out what my legal rights are before I say anything else. Thank you for all the support.

I am not a police officer, nor a judge. And the accusations against Marostica have never been tested in court. All we know is that in 2019, while Marostica was loudly calling out other comedians for their supposed lapses, this leader of stand-up’s ultra-progressive faction was being accused by multiple individuals of abuse. And like C.K., Marostica admitted to wrongdoing. On October 11th, 2019, Marostica posted a long apology that began as vague and contrite (“I promise to every single person that needs to hear it that I can and will be accountable, wear the full weight of the accusations against me, and I will change”), but then veered into specific self-exculpatory arguments (“I cannot be sorry or be held accountable for things I legitimately did not do. While in a relationship … I was choked out without consent, was pressured into sex on several occasions, and was shamed for not being able to have sex due to dysphoria.” Marostica then retreated from public life, and hasn’t performed (to my knowledge) since. The same comedian who’d received a flurry of fawning profiles in 2018 and 2019 had now become, to the Canadian arts press and the various awards committees, a non-person.

Not that Marostica’s name has been forgotten. Far from it: On the various hyper-integrated social networks that serve Canada’s (highly gossipy) stand-up comedians, the scandal dominated our discourse. And “pulling a Chanty” has come to be known, among some of us at least, as synonymous with accusing others of immorality as a way of deflecting attention from one’s own behaviour. But with scant exceptions, all of this chatter is below the surface, and Marostica has not been “cancelled” in any public way, perhaps because few of Marostica’s erstwhile boosters wanted to suffer the humiliation-by-association that this would entail.

After Alberta comedian Brett Forte noted the similarity between a joke he once told and a 2020 news story in which a Sikh man used the fabric of his turban as a rope to save a drowning child, he received major backlash and a deluge of death threats. Forte also had a clip of his material (not containing the turban joke) removed from the website of the CBC, Canada’s (highly progressive) national broadcaster. Yet Marostica’s material is still up.

Not everyone agreed to keep Marostica’s downfall out of public view, however. One video about the claims against the comedian has been viewed almost 800,000 times (making it several orders of decimal magnitude more popular than Marostica’s actual comedy).

This was the work of the taboo-busting Montreal duo known as Aba & Preach—aka comedian Aba Atlas and Erich “Preach” Étienne. Along with his commentary on Marostica contained in the video, Atlas also criticizes the growth of so-called “safe space” comedy rooms, which promise comedians an environment free of sexist jokes and other forms of retrograde humor. Atlas noted that these venues, paradoxically, can become breeding grounds for predation by engendering a false sense of security; and by allowing abusers to virtue signal as a means to address the cognitive dissonance created by their own wrongdoing (a phenomenon known in psychology, more broadly, as “self-licensing”). The video ends with a call to action directed at the media organizations that had been giving Marostica so much positive attention:

I want all the big media outlets … CBC Radio, CTV—all the ones who’ve been putting Chanty up, all the time, as some kind of icon and role model for us to follow—I want you guys to come out and say something about this too, right? You guys want to take the time to bash Louis C.K. because he’s on a big platform, but what happens when one of your own is engaged in far more egregious forms of abuse? Everybody wants to be self-righteous, but nobody wants to look at themselves and their own behaviour.”

But nearly two years later, there’s been no public accounting for l’affaire Marostica—certainly no restitution to Matt Billon or anyone else whom the comedian targeted (or at least none that I’m aware of). This is one of the reasons I wrote this article.

And there are lessons here that go well beyond comedy. While the vast majority of my readers (even the Canadian ones) have never heard of Marostica, Rawsome, or the rest of her clique, the examples I discuss herein show how, in the current milieu, tiny groups of ideological enforcers can poison an entire artistic subculture, despite these enforcers’ lack of any real commercial success or name recognition among the general public.

“Cancel culture” has become a trendy term in recent years. But public shaming has always existed. It’s a social tool, and like all tools can be used for good or ill. Moreover, it can be hard to have a productive conversation about cancel culture, because we all have different ideas about what it encompasses. But in general, it’s taken to include, in descending order of moral defensibility, some combination of the following:

- Holding to account powerful predators (Harvey Weinstein, for example), whose influence and wealth otherwise shield them from justice.

- The shaming of individuals, whether powerful or not, by their victims, as a means to warn other members of a community, so that they can avoid suffering similar harm.

- Punishing individuals for perceived bigotry, “incorrect” political opinions, and other alleged failings that fall well short of criminal behaviour.

- Pressuring an organization into firing, shaming, or otherwise canceling an employee, supplier, contractor, or affiliate (often someone who falls into Category #3, above)—or removing his or her material from circulation.

- Spreading fraudulent or exaggerated claims of wrongdoing as a means to call out private individuals and subject them to harassment.

- Inciting a mob to enact vigilante justice against a person perceived of wrongdoing.

The first and second bullet points are what most progressives have in mind when they claim that “cancel culture” is just a term of abuse aimed at discrediting the campaign to hold bad actors accountable. The fifth and sixth represent practices that are unambiguously immoral and dangerous. The third and fourth are the grey areas, highly dependent on context. And it is in these due-process-free grey zones where much of the Canadian comedy meltdown has occurred. A mob caught in the rush of the moment, and high on its own sense of moral righteousness, has no capacity for proportionality. Guilt is simply assumed, and summary excommunication is the expected sentence.

There is real prejudice and hatred in the world, of course, and most of the people arguing for social justice do so sincerely. But the movement has been weaponized by small, cynical cliques in many fields—including my own, Canadian comedy, wherein certain producers and performers have appointed themselves judge and jury. And these activists have predictably baked their own biases, bigotries, and professional conflicts of interest into their judgments, often pursuing private vendettas under the guise of social justice.

And no, the fact that comedians pride themselves on their irreverent spirit in speaking truth to power hasn’t helped us escape this dynamic: The sanctimonious language of victimhood is treated as a sort of holy writ, and so trumps irony, satire, and caustic skepticism, the comedians’ usual stock-in-trade.

It would be one thing if comedians were enduring this increasingly toxic and constrictive atmosphere as the price they pay for a lucrative career. But independent stand-up comedy—i.e., comedian-run shows that operate out of local bars and restaurants on a weekly, monthly, or pop-up basis—is an absurdly low-paying industry. Stage time is scarce, with what few opportunities exist typically being doled out on the basis of nepotistic connections or cronyism.

If you’ve ever attended an indie comedy show, paying your $15 at the door, you might assume that some portion of that money would make its way from the cashbox into the pockets of the performers on stage. It’s an understandable misconception. But the reality is that many if not most comedians don’t get paid, except perhaps in the form of a few free drinks. In many cases, only the host and headliner are compensated for their time.

In fact, for all the talk of social justice one hears in these circles, there’s an explicit double standard that allows comedians to underpay each other. While a performer might get $500 to perform even a low-end corporate gig, or $200 to headline at a dedicated comedy club, they can expect about a 10th to a fifth of that to headline an indie bar gig run by fellow comics. Many comedians actually lose money for every show they do, due to the cost of transportation, food, liquid courage, and other expenses.

To be fair, it should be noted that even well-known pro comics will occasionally do these low-paid gigs as a way to practice new material, or simply so they have something to do on a Monday night (when the full-time comedy clubs are typically closed). But for a lot of “amateur” performers, the indie circuit is all they have, and the assumption that most comedians don’t deserve real pay undermines both the quality and size of the available talent pool.

I should note that “amateur” is a rather slippery word in the comedy world, as many quote-unquote amateur comics have shown that they’re good enough to perform in front of paying customers, and may have even generated a decent social-media following over the years. Before COVID temporarily closed down the live comedy industry, in fact, many of the “amateurs” I know performed at booked shows several times per week.

The easiest way for an amateur to get invited to perform on a show is to be friendly with the producer. Second easiest is to organize a show of your own and trade spots. The third option is to direct-message the producer on social media, which is a standard method of professional contact in the field. This highly personal, friends-first approach gives producers and bookers huge power over the people they put on stage. It also allows interpersonal conflicts to spill over into the professional sphere. This is especially so in modest, largely self-contained urban markets such as Vancouver, where power is centralized in the hands of a few venues and a small coalition of indie bookers who like to throw their weight around.

Dedicated comedy clubs, on the other hand, usually hew to a higher standard of professionalism because they receive greater scrutiny from the arts press, and because maintaining professional business practices is the best way to stay in business and pay the rent. But these clubs (not to mention festivals, media companies, and record labels) tend to recruit their bookers and management from indie circles—which means that, over time, local relationships and conflicts tend to make their way up the food chain into the world of corporate comedy.

Even a successful comedian who gets picked up as a comedy-club regular will face a power imbalance: The largest comedy chain in Canada, Yuk Yuk’s, has been criticized for having domestic comedians sign non-compete clauses, which require them not to perform at other clubs in cities that have a Yuk Yuk’s location. Yet the signed comic isn’t guaranteed a minimum level of stage time, nor income. These practices make it harder for other clubs to operate on an even competitive footing in Canadian cities, since they can’t recruit talent that’s been claimed by Yuk Yuk’s.

All in all, even most outwardly successful full-time comedians still make an annual income that sits significantly below the poverty line. As such, the performers that the industry tends to retain are middle-to-upper class young people with financial support from their family (topped up, in some cases, by government benefits such as unemployment insurance and disability), a white-collar day job that lets them put food on the table, no dependants, and a schedule that permits them to dedicate their evenings to what is effectively a life of endless unpaid auditions. Unsurprisingly, the field has a massive attrition rate; with working-class people having an especially hard time. (Comedians, even those with blue-collar roots, generally have had some degree of post-secondary education. Think of your average successful comedian as a failed member of the professional class: somebody who could have been a lawyer under different circumstances.)

For reasons that haven’t been formally studied (to my knowledge), the attrition rate is roughly similar among women (relatively few of whom enter the field to begin with). And this fact has spawned much of the social-justice activism within stand-up culture, the idea being that the lack of parity in representation is de facto evidence of extreme gender discrimination. While comprehensive statistics are hard to come by, my experience in every city I’ve been to suggests that somewhere between 80 percent to 90 percent of my fellow comics are male—though women do tend to occupy a comparatively high number of managerial and organizational off-stage functions.

There has been a relative increase in the ranks of female stand-up comedians over the years, thanks to the lowered stigma against women hanging out in bars telling bawdy stories (as well as broader social factors, such as the drop in average family size, delayed childbirth, and higher female participation in the economy more generally). But even so, a stand-up show where a third of performers are female usually reflects a significant over-representation of the available pool of female talent. This is especially true at the elite level, as the average female comedian is less experienced than the average male comedian in most markets. Unfortunately, this imbalance in experience can end up encouraging the stereotype that women aren’t funny, as audience members have no idea that the female comics they see on stage are years behind the male comics in their professional development. It’s difficult to stretch 10-20 percent of the population into 30-50 percent of the roles, and the gap is going to betray itself, one way or another.

A popular view in stand-up comedy is that the gender imbalance is culturally rooted in the field’s hyper-masculine social environment, not to mention the harassment and misogyny endured by female comics. But my own experience (as well the persistence of a wide gender gap, even following the industry’s effort to embrace women in recent decades), suggests that a combination of gendered differences in socialization, risk tolerance, and lifestyle barriers are at least equally important factors.

The truth is that, notwithstanding the sexism that female comics often endure, demand for female performers is high among clubs and bookers, and women now enjoy a major structural advantage over their male counterparts when it comes to getting stage time. Mention that in front of the wrong producer, however, and you might just wind up blacklisted: We want affirmative action, but we don’t want to acknowledge that it’s affirmative action—perhaps because that might open a door to asking if we’re actually doing it right.

In Canada, stand-up comedy is one of the few types of live performance that generally isn’t directly eligible for government grants. But the fact that individual comics can’t get funding doesn’t mean the industry itself doesn’t receive public money. In general, that funding goes to festivals such as (the above-mentioned) Just for Laughs, whose resources come with power over performers. And like all arts grants, these ones often are tied (whether formally or informally) to diversity mandates—despite the fact that festival organizers have no control over the racial or sexual makeup of the talent pool from which they’re recruiting. Systemic bigotry against minorities does exist in our society, but it has far more to do with broad societal structures and attitudes than whether or not any given open-mic comedy bar has an official sexual-harassment policy.

In practice, the diversity mandates mean that gay, female, and non-white performers aren’t just talent—they’re a commodity that event organizers can leverage to earn money, protect themselves from criticism, and project moral influence. In other words, it’s the same kind of incentive system that’s been playing out all over the cultural landscape in recent years: Rather than growing the number of diverse performers at the grass-roots level, or making the industry more economically attractive to people who don’t enjoy white-collar middle-class privilege, gatekeepers find it easier to gerrymander their most visible talent by excluding or limiting people who don’t belong to the favoured groups.

As in most spheres of Canadian entertainment, CBC’s notoriously bland, quota-driven approach is a large part of the problem. With its state funding, our national broadcaster should be able to assemble an all-star line-up. Instead, CBC’s New Wave of Stand Up, which purports to showcase the country’s “hottest new comics,” hits a quality level that hovers somewhere between “decent” and “passable amateur night.” Yes, CBC executives are eager to highlight queer comedians. But they don’t seem to pick the best queer comedians, which bothers me as a queer comedian. Frankly, it also bothers me as a comedy lover and a believer in meritocracy. And I’m sure other “equity-seeking” groups, to use the preferred parlance, have similar complaints.

The state of institutionally supported comedy in Canada is reflected by the “Best Comedy Album” category of the Juno Awards. Being the only non-music album award associated with the Junos, it’s always been an odd duck—made odder by the fact that it’s been awarded only eight times in total over the last five decades (including annually over the past four years), and comes with no minimum qualifications in regard to streaming viewership or sales. If it did, many of the most recent nominees likely would never have qualified.

One would expect such an award to have significant competition from the giants of Canadian comedy—Norm McDonald, Russell Peters, Bonnie McFarlane, or Steve-O (of Jackass fame). Instead, nominations for the Juno tend to be dominated by debut albums from relatively inexperienced comics. Aside from Marostica, I won’t name names. But I’ve listened to every winner and nominee from the last three years and can attest that an unsettlingly high number of these comics come from the shallow end of the Canadian comedy pool.

One of the problems is that the safe-space comedy trend has normalized a lowered standard of comic professionalism, because the genre allows (and sometimes even encourages) verbal flubs and faux-nervous giggles, which experienced comedians recognize as signs of inexperience that hamper a joke’s proper pacing. While a safe-space audience might laugh supportively at these indicators of vulnerability, a mainstream club audience expects more polish. Safe-space comics also tend to “stay in their lane” to the point of caricature, often joking exclusively about their most immediately obvious identity characteristics.

Out of 13 tracks on Marostica’s The Chanty Show, for instance, 12 are about gender, 11 are about being gay, and one is about having hair like an ice cream cone. The overall effect is strangely impersonal, because by the time the 45-minute album is over, a listener is inclined to wonder if Marostica has any hobbies, interests, or even identity outside of being queer. Bits include Misgendered, wherein Marostica talks about being mistaken for a man from behind, then feeling cheated out of a fun reaction when they turn around and are likewise mistaken for a man from the front. This is some of Marostica’s better work, and includes a list of other people whom they could be mistaken for, like “Annie Lennox dressed as a war veteran,” “Guy Fieri: the College Years,” and “Justin Bieber’s Twin Aunt.” But only two tracks later, we have Celebrities I Look Like, a far more generic bit dedicated to the (implausible) premise that men mistake Marostica for celebrities such as Miley Cyrus, K.D. Lang, and Justin Bieber himself.

There’s an audience for the kind of comedy Marostica performs (or performed, depending on whether a comeback is in the offing). However, it lacks mainstream appeal, judging not only by the very low levels of audience engagement on streaming sites, but also the looks on my (non-comedian) friends’ faces when I forced them to listen. Obviously, taste in comedy is subjective. But speaking as someone who generally likes queer comedy material, I found Marostica’s work alarmingly amateurish (in the commonly used sense of the term). And it isn’t credible that Marostica earned one of the top prizes in Canadian comedy, let alone three, on the basis of actually being funny.

What Marostica had, for a time at least, was the right connections. In another age, the primary way that comedians networked with one another was to appear at the same venues, and watch one another perform. But that is changing thanks to the clustering of comedians within social-media groups segregated by gender or progressive in-group status, wherein members inculcate a strong us-vs-them ethos, pressure one another to support other in-group members, and organize mob campaigns against perceived enemies. The coin of the realm in these fora isn’t humour, or even formal institutional power, but ideological correctness. Yes, these comedians also network in the traditional way, at actual comedy shows (when there’s no pandemic going on, at least). But when these events are safe-space shows with tiny crowds, the main goal tends to be signalling correct attitudes, as opposed to getting laughs.

At this point, I know what you’re thinking: Why should I care about who receives a parochial Canadian comedy award? And it’s a fair question. However, it’s not the Junos or Marostica that I’m really concerned with here, but rather the larger pattern that they represent, and which may be observed all over the arts world: an artificially constructed, publicly funded hierarchy, presided over by a small group of ideologically homogeneous gatekeepers, completely divorced from questions of merit or popular taste. This is a world in which Louis C.K. is a “bad” comedian, despite his enormous following, because he did bad things, while pre-exile Marostica was a “good” comedian, despite not being funny. (One of the reasons why there was almost no follow-up coverage to Marostica’s exit from comedy is that there was no fan base to ask awkward questions about upcoming shows.)

The Juno Awards show how this process works: The award for Best Comedy Album first passes through a screening committee of 10–12 members. Then a panel of 10 judges votes in two rounds, first to narrow the field to a shortlist of five nominees, then to pick a winner. The judges are selected from volunteers from within the comedy industry, balanced for geographical distribution, gender parity, and inclusion of LGBT, indigenous, black, and other minority voices. There doesn’t appear to be any requirement in terms of reputation or achievement for judges or selection-committee members. Of course, there is nothing wrong with wanting to be inclusive, nor with welcoming some of the disproportionately influential female and queer producers who run hyper-politicized “safe-space” comedy rooms. But the nature of recent nominations suggests that this crowd now dominates the selection process, to the exclusion of those who actually understand and appreciate the mainstream comedy market. Again, I don’t want to focus on particular individuals here, and so I won’t name names. But, by way of example, I will say that one of the Juno judges from a previous year, someone I know, runs an extremely small safe-space monthly show that can only be described as painfully unfunny.

By contrast, the (apparently defunct) Canadian Comedy Awards, like SiriusXM’s Top Comic award, allow the public to vote, which one might imagine to be a reliable means to reflect mainstream opinion. But these processes can easily be co-opted by social-media campaigns, especially since people are typically allowed to vote more than once. The Vancouver comedy scene, for instance, has two significant networking forums, including one exclusively oriented toward female and non-gender-conforming comedians (Vancouver Ladyish Comedians), wherein it is common to find posts organizing mass-enlistment vote campaigns on behalf of this or that member of the local scene, sometimes explaining how best to game the system through the use of multiple devices or incognito browser settings.

Canadian comedians care deeply about these awards, as even a mere nomination brings media exposure and the possibility of future opportunities. But given that the outcomes are clearly out of line with real merit, how are we supposed to trust the process? Eventually, the public will learn to simply ignore these awards. Indeed, the example of Marostica suggests they’ve already done so.

Stand-up comedians aren’t like other live performers, who can practice at home, by themselves. A guitarist, painter, or novelist can hone his or her art while sitting alone in a tiny apartment. But stand-up comedians need an audience to test their material.

In theory, anyone can get stage time by just showing up at an open-mic evening, the subset of the amateur field that’s open to those who haven’t yet gotten to the booking stage. At open-mic nights, the comedy ranges from genius-in-the-making to sets so radioactively awful you should only watch them through several feet of specially treated glass. Judging by all the ones I’ve been to, at least a third of the participants at your average open-mic event are suffering some form of clinical depression, and the odds are high that someone will either take off their clothes or cry.

But in Vancouver—and I’m guessing, in other cities—even these supposedly “open” mic events aren’t typically “open” to everyone. A few people get explicitly banned when they fall afoul of official and unofficial rules about content, while others are merely made aware that they’re not welcome to return. If you’re an ambitious comedian, you’re careful to laugh hardest at the comics with the right connections, and not at all at the comics who’ve been deemed persona non grata. The safest path is simply not to laugh at anyone you don’t know, which can be discouraging to comics who aren’t members of the ascendant clique. The zero-sum mentality of amateur comedians leads to a great deal of jealousy, gossip, and interpersonal sabotage, as we too often view each other not as colleagues, but rivals for a small, fixed number of (low quality) opportunities.

Most Vancouver open-mic venues have a ban on “hate speech”—though the term is defined in different ways depending on the comic and the comedic subject. Established comedians visiting from outside the city are rarely targeted, while a low-status local who makes a joke along the lines of “sometimes, women in my life do things that are silly or unfair,” “black people and white people exhibit cultural differences,” or “the word niggardly sounds a lot like a racial slur, but isn’t,” may quickly find themselves disinvited or shunned by people they once considered friends. This process is managed with the usual whisper campaigns, often through private social-media posts that feature the joke in question quoted in a way that strips away context and maximizes reputational damage. In many cases I’ve observed, these were jokes that an in-group member of the local scene could make verbatim with no consequences.

This I know, because I’ve been relatively popular with the safe space in-crowd, and I frequently make jokes based on premises that have gotten other comedians booed off stage by their peers. In late 2018, a newbie comic by the stage name Justin Chan the Asian Man infamously introduced himself to safe space comedy by referring to himself as a retard and insulting the previous performer on stage, thereby eliciting immediate fury from the assembled comics. Earlier that year, I had, at the exact same venue, performed a set about my psychiatrist, calling myself a “strong, independent retard who don’t need no shrink” to laughter and applause. (While Justin Chan has severe ADHD, I have a barely-noticeable case of autism.) Likewise, casually insulting a previous comic is an old tradition in stand up, and it doesn’t make sense to punish a new comedian for trying and failing to pull it off.

When you think of “cancelled” comedians, your mind likely turns to well-known figures such as Louis C.K. But below the radar, cancel campaigns overwhelmingly target marginal, socially vulnerable members of the community, the vast majority of whom have (to my knowledge) done nothing worthy of getting mobbed. Nick Roy, a 20-year veteran of Canadian comedy, tells me that the favoritism, fickle friendships, and general cattiness of the stand-up world preceded the age of Twitter. The difference between then and now, he says, is how low the bar for blacklisting has fallen, and how much a single vengeful producer or fellow comic can amplify the case against a targeted individual through social media. “To get banned back in the day, you used to have to punch a waitress or break a toilet or [sleep with] the boss’s wife,” he told me. “Now, it’s easy. You don’t even have to do anything.”

In part, the current situation results from a well-intentioned campaign to rid stand-up comedy of the old power structure, which operated through cliques of unaccountable and unprofessional (mostly white, mostly male) owners and bookers. But as the progressive, explicitly feminist, diversity-oriented safe-space crowd became influential in recent years, its leaders didn’t fix this problem. They just swapped out the beneficiaries. While the bullies who dominate the Vancouver scene (the one I’m familiar with), come in all shapes and sizes, those who use the most vicious methods (doxing, social-media intimidation, harassment of venues) tend to skew sharply younger.

Comedians once venerated say-anything renegades such as Lenny Bruce. But many of today’s progressive comics have embraced the idea that no one, on stage or off, has the right to discomfort them—with discomfort being broadly defined. Terms such as “safety,” “danger,” and “comfort” appear often in their social-media manifestos, frequently in euphemistic ways that serve to effectively exclude those who don’t share their refined, college-educated worldview. The belittled group they target tends toward social awkwardness, working-class roots, and men with an overtly masculine comedic approach. One of the problems with political correctness is the degree to which it confuses politeness with morality. And it is generally the people in power who define what’s polite and what isn’t.

And it isn’t just the content of a comedian’s set that can be targeted: Even private or semi-private online arguments or complaints about one’s personal relationships can set off cascading torrents of harassment. Restaurants and bars that host targeted comedians may receive vague but serious-sounding warnings about the “problematic” performer scheduled to appear. Even if it weren’t for the (very real) threat of these establishments being “review-bombed” by online mobs, restauranteurs and bar owners generally have little interest in navigating these obscure comedy-world dramas; and so the path of least resistance is simply to cancel the event in question. One comedian, Mark Hughes, recently had a sold-out show cancelled during a partial lift in lockdown, after the manager received a single ominous email from someone with the charming sobriquet “buttchugger604,” citing one of Hughes’s social media posts.

It can be hard to explain the fear caused by these whisper campaigns to someone who has never been targeted by one. The attacked individual knows that anything they say—or have said—will be taken maliciously out of context. You never know who’s heard what, and you can never properly explain yourself because many people won’t speak to you. Many victims exist in a state of paranoia. Was that show you got kicked off really overbooked—or was that just a pretext?

This isn’t just a problem for comedians. It’s also a problem for comedy. Most good comedians start out as bad comedians. And most good jokes about sensitive topics start out as bad jokes about sensitive topics. This is why the impulse to harshly punish a low-level comic for making an uncomfortable joke (even in private) is corrosive to comedy: It has a chilling effect on experimentation and prevents comedians from taking artistic risks.

What’s worse, there is no one in the industry—at least not at the local level—who’s willing and able to call the problem out, since indie producers, and even many arts writers who cover the comedy scene, are either amateur comedians themselves, or are tied in to the scene through social, romantic, or professional relationships.

By way of example, consider a recent article entitled “Nasty Women Are Funny Women: Vancouver comedy festival lets women-identified and non-binary performers take centre stage,” in which a writer for Vancouver’s highly-progressive Tyee magazine profiles a comedy festival that aims to spotlight “women, trans, and non-binary performers.” A host and curator at that event was the Tyee’s own outreach manager. When Parton and Pearl, a publication specializing in comedy and country music, covered “Queer Comedic Artists in Vancouver You Should Know!,” one of the most glowing profiles was dedicated to Tin Lorica, who produced a comedy show, Millennial Line, alongside Savannah Erasmus, the article’s author. (These relationships are not necessarily corrupt, but they hardly lend themselves to objective coverage. Moreover, I know—and like—most of the people involved, which is part of why critiquing these arrangements can be difficult.)

There’s nothing wrong, per se, with having “safe space” comedy rooms or women-focused comedy festivals, in the same way that there’s nothing wrong with a Spanish-only movie theatre. In both examples, the venues serve niche markets. The problem I’ve witnessed in Vancouver, however, is that influential proponents of safe-space shows don’t see their preferred comedy style as one niche among many: They see it as the only permissible niche. The paternalistic premise at play is that certain groups, particularly women, shouldn’t be exposed to politically incorrect jokes, even if they make the informed decision to opt into such comedic environments as comedians or audience members. I know many aspiring comedians, both men and women, who’ve quit the business simply because they couldn’t stand this judgmental environment.

Moreover, since the safe-space conceit is based on the idea that female, non-white, and queer comedians are at risk of predation and bigotry in other, “unsafe” parts of the comedy world, there is a built-in incentive to exaggerate those threats. When I began my own foray into stand-up, I was repeatedly warned about one particular small-time producer—a kindly but awkward older man. My original mentor in the Vancouver comedy scene (a woman mentioned elsewhere in this essay) even suggested to me that he was a sexual predator. I later learned that this lurid allegation was based on a single woman’s claim that she thought he may have been flirting with her.

These dubious allegations reverberate like sound waves in a tiny, windowless room, because much of the discussion within Vancouver’s stand-up comedy scene is based around a single private Facebook group, which also serves as a hub for performing opportunities. Since a comedian who gets banned from this group will have difficulty getting bookings, the group’s admins are able to exercise at least some measure of control on who works and who doesn’t. In several instances, comedians who’ve been banned and marked out by the safe-space faction as problematic have also been targeted for mass-blocking on private social media channels as a means to lock in their excommunicated status. Those who continue to interact with these individuals (even privately) are themselves at risk of excommunication. In fact, it is a common pattern for comedians who associate with a targeted individual (or even an explicit critic of the field’s social-justice faction) to find themselves on the receiving end of anonymous emails accusing them vaguely of bigotry and other forms of wrongdoing.

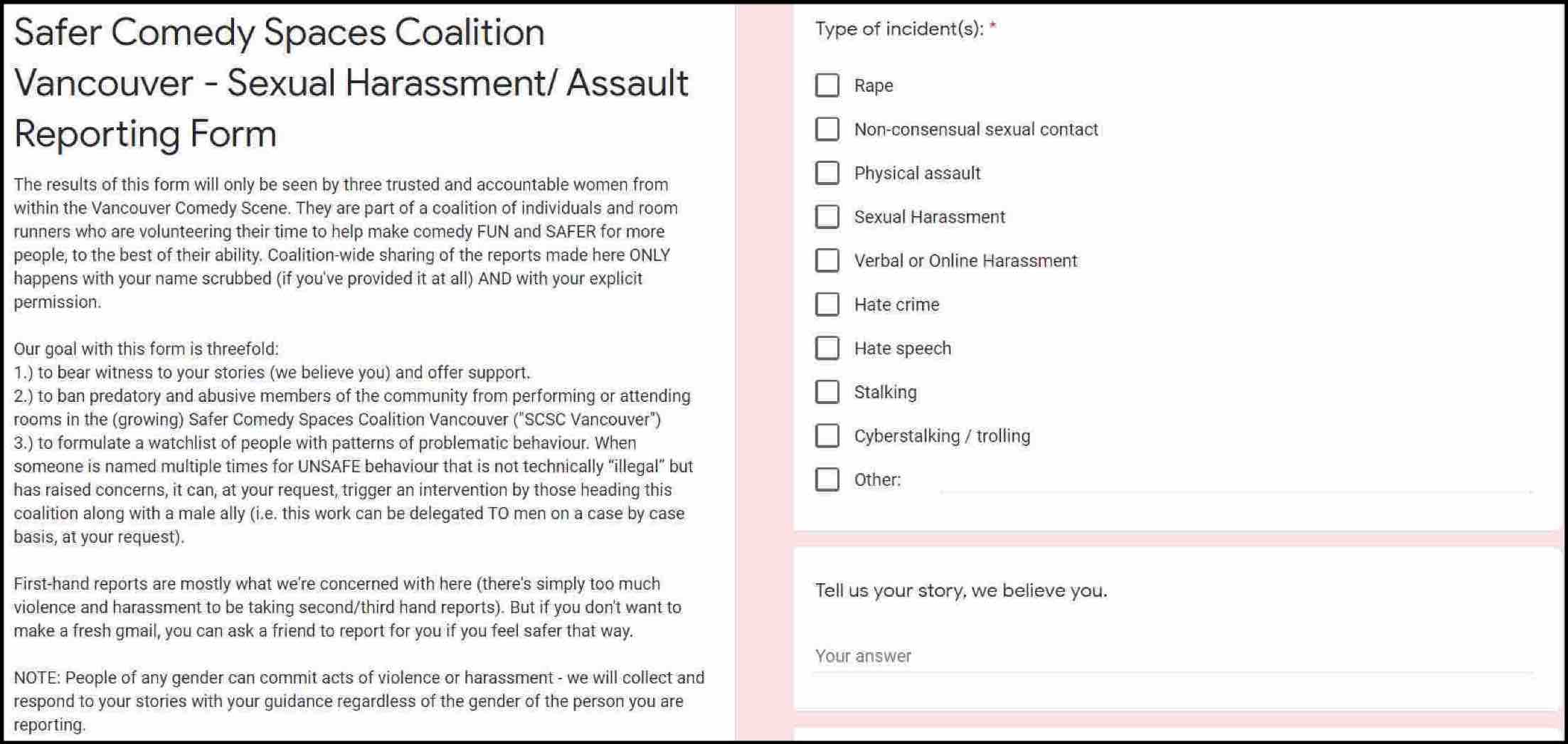

In early 2018, a small group of safe space producers, including Rawsome, set up an anonymous Google form tip-line (analogous to Moira Donegan’s “Shitty Media Men” list), so that members of the stand-up community could report allegations of anything from aggressive speech to sexual abuse. While this public effort fell apart, the idea behind it didn’t. A few months later, a flurry of sexual misconduct allegations were posted directly to the Facebook group. Some of the allegations were posted by the claimed victims, but others were anonymous or presented by a third party. Unlike the cases of Louis C.K. and Chanty Marostica, this was not multiple accusers coming forward against a single alleged perpetrator and corroborating the shared details of each other’s cases. Rather, most of the accusations were of single instances of misconduct or abuse.

It seemed like a potential witch hunt, but anyone who pointed this out became vulnerable to their own cancel campaign. Adam Zed, a comedian who was blocked from the Facebook forum for pointing out that sexual-assault accusations should be adjudicated by the police, not members of a stand-up networking forum, withdrew from active participation in the scene. Another comedian, a woman, was publicly shamed for failing to distance herself from one of the men accused, and was labelled a rape apologist on the women’s forum. She ended up leaving for the United States after being frozen out of the Vancouver market. Various other comedians (with no allegations against them) also left the city, and sometimes even Canada, in fear of the increasingly paranoid social environment. (Meanwhile, the man who’d been accused of abuse in this particular case hired a lawyer and had the accusation retracted.)

In early 2019, news broke of an alleged sexual assault at a comedy venue, reportedly perpetrated by an Asian assailant. The safe-space hive mind immediately concluded that the perpetrator had to be the aforementioned Justin Chan the Asian Man, whose gonzo performances had already gotten him banned from several bar shows and clubs (in no small part due to pressure from Suzy Rawsome). Someone had even contacted the police, identifying Chan as the assailant—even though Chan, a former bodybuilder and personal trainer, bore no connection (except race) to the reported assailant, who was described as a fat man with glasses. It was one of those darkly hilarious moments you couldn’t make up: Some of the most progressive white people in Vancouver’s stand-up comedy scene apparently can’t tell Asian people apart.

Chan bleached his hair soon after, as a means to defend against future allegations. In his words: “It’s an accountability measure. If I ever rape anybody, it’ll be really easy to find me. Because the hair.” But jokes aside, Chan suffered real emotional scars as a result of two years of ostracism and abuse. He told me that “I’ve lived all around the world, and I’ve never experienced prejudice and discrimination like I did in Vancouver from white comedians.”

Even when Chan was reduced to acting as a volunteer doorman at a Vancouver venue called the Comedy Lizard in 2020, Rawsome campaigned on Facebook to get him removed from that position, too, insisting that his presence made the comedy club “unsafe.” (James Burr, one of the few black producers in the city, had taken a chance on Chan because of his willingness to do a thankless, yet important job like manning the door, and tried to stand by Chan despite the pressure.)

Another Vancouver comedian who’s endured abuse is Andrew Draper, a blue-collar comedian with no entrée among Rawsome’s in-group crowd. His sin was making a joke, on his own Facebook page, to the effect of having “just unfriended everyone who isn’t racist,” an obviously tongue-in-cheek send-up of virtue signalers who announce political culls of their social media friend lists. In Draper’s case, the mob was led by Ola Dada, a Nigerian-Canadian comedian. Draper was forced to block large swaths of the Vancouver scene, changed his name on social media, and, eventually, gave up on the city entirely and moved away—this after three years spent bending over backwards to please Vancouver’s safe-space comedians while trying to remain true to his own working-class style. (As for Dada, he was featured on CBC Comedy’s The New Wave of Standup just a few weeks after leading Draper’s mobbing.)

On the other hand, it’s hard to blame Dada for believing that he can get away with this kind of behaviour. As one of the few black performers in Vancouver, he is a coveted diversity asset. And his position in the intersectional status hierarchy pretty much guarantees that he will win every public argument. As an accepted queer performer and member of the same cozy safe-space circles, I got the uneasy sense that I likewise could say pretty much anything about somebody unpopular with the group, so long as it fit the existing narrative. That realization is what eventually turned my stomach.

As terrible as the last year and a half has been, it also brought me a sense of relief from the narrow, clannish world of Vancouver comedy. Online shows introduced me to wonderful and genuinely talented performers from all across the world. In the short stretches during which lockdown was lifted and live shows were allowed, I felt more relaxed around my fellow comedians, despite the masks and two-metre space-bubbles. That’s because, for the most part, it was the risk-tolerant performers who were active, while the safe-space comedians remained at home. For the first time in years, it felt like a real community.

It also allowed me some time to think about how to fix things. In the long run, the only way stand-up subculture can thrive is if we find some way to decentralize the de facto power structure, and ensure that small, insular groups aren’t in a position to set conditions on what kind of jokes we tell, and what kind of opinions we share. It’s unclear how this gets done. But certainly, a starting point would be for CBC, CTV, SiriusXM, and other media companies to do a serious audit of their comedy divisions. Perhaps new staff and processes could be put in place to ensure that the comedians who get showcased are actually telling jokes that the world finds funny. Bookers for comedy clubs and festivals might want to keep an eye on diversity to ensure a multifaceted experience for audiences and avoid unintentional discrimination, but that should never trump the ultimate goal, which is to entertain. The taxpayer-funded CBC in particular has a duty to serve the interests of Canadians, and that means quality content that people want to watch.

Prestigious comedy awards need to be reflective of merit, not a popularity contest among people no one outside of the industry has ever heard of. These awards can make or break careers, and hundreds of comedians compete for them every year. Award winners should act as our guiding star as professional and amateur comedians and set the standard of great comedy. Either that, or they shouldn’t exist.

At the local level, grass-roots comedians need to find their nerve. Most people aren’t intentionally involved in the bullying, but an unwillingness to stand for those who are targeted is what enables this to happen. Again, there’s room for safe-space comedy, insofar as it is presented as one menu option among many—not an inquisition whose jurisdiction extends to everyone. We need to adopt higher standards. We need critical arts journalism, not just diversity puff pieces written by our friends. We need to reject cronyism and penalize those who try to get ahead by hurting and excluding others. We also need to accept that while diversity is a worthy goal, diversity itself doesn’t guarantee good comedy. Korean-Canadians didn’t like Kim’s Convenience just because it featured Korean actors and made them feel included: They liked it because it was funny. Likewise, I enjoy seeing gay entertainers featured prominently in media. But if it’s not good, I won’t watch.

The problem of how to respond to ambiguous abuse allegations, with insufficient corroboration to support prosecution or even extensive police investigation, is a difficult and thorny one. We need to reduce the opportunity for abuse without appointing ourselves judge and jury. We need to address egregious, well-documented cases of wrongdoing when and where possible, but our ability to police ourselves is limited by our interlocking relationships. Harm reduction, rather than retribution, seems the best approach. Allowing performers to preemptively request not to be booked on shows with other, specific performers without needing to provide an explanation is one approach; but allowing performers to insist that another performer be blacklisted entirely is likely opening up its own avenue for abuse.

Putting issues of identity to one side, we need to find a more sustainable business model for indie comedy shows, improved labour standards, and increased pay. And no, as the Canadian example shows, the solution isn’t more government grants—which often end up in the pocket of people who tell bad jokes but have the right friends. Moreover, government grants, and the diversity mandates that come with them, typically are predicated on the assumption that the comedy scene should be perfectly representative of the demographics of the country as a whole. We need to accept that a disproportionate number of men want to do stand-up, just like a disproportionate number of women want to be novelists. Japanese immigrants are more likely than Russians to play baseball, and a statistically anomalous number of competitive Tetris players are on the autistic spectrum. That’s okay. It’s fine.

Stand-up comedy traditionally has been a place where people like me use humour to talk about emotionally loaded topics, and hopefully experience a sense of catharsis in the process. Comedy clubs are usually dimly lit, so that audience members can relax in the cloak of anonymity offered by darkness—laughing at the things they’re not supposed to find funny. But the people on stage have no choice but to stand in the light. That has always made us vulnerable. But now, for the first time, it has made us afraid to speak the truth.

It’s easy to blame the troubles of the comedy industry on the oversensitivity of the general public. But it isn’t the audience that’s our problem. The truth is that the people who need to relax, open their minds to new ideas, and stop being so judgmental are the ones holding the microphones.