Books

The Subversive Simone Weil—A Review

Chastising the followers of Marx for ignoring workers’ actual experiences, Weil was almost a nominalist, and she awaited insights, as opposed to going in search of them.

A review of The Subversive Simone Weil: A Life in Five Ideas, by Robert Zaretsky. The University of Chicago Press, 181 pages. (February 2021)

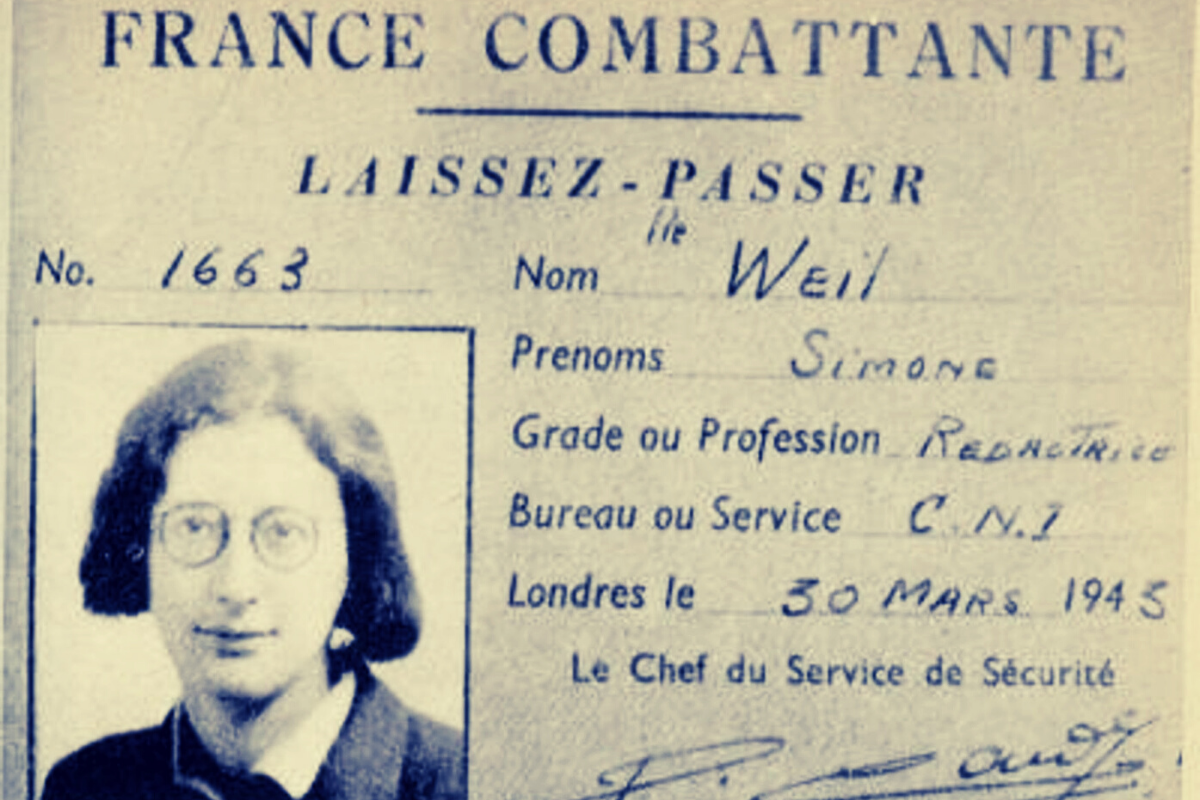

“How much time do you devote each day to thinking?” That’s a strange question to ask a nurse from one’s hospital bed, but Simone Weil was no ordinary patient. On the contrary, philosopher, mystic, and, at that time, member of the Provisional French government in London, Weil was in every sense extraordinary.

Praised by André Gide as the “patron saint of all outsiders,” known to her fellow students at the École Normale Supérieure (ENS) as the “Categorical Imperative in skirts,” and dismissed by Charles de Gaulle as “a crazy woman,” Weil was certainly unusual. At once charmingly amusing and maddeningly irritating without meaning to be either, Weil was a bona fide eccentric. As T.S. Eliot pointed out, one detects no sense of humour in Weil. Candid to a fault and always in dogged pursuit of the Good, she believed that thinking is what gives us dignity and protects us from tyranny. The unusual question she put to her nurse, in other words, was to her mind perfectly reasonable.

After refusing food and treatment for her tuberculosis-damaged lungs, Simone Weil died in Grosvenor Sanatorium in Ashford, Kent in 1943. An archetypal anti-philosopher, her life was as idiosyncratic as her thought. Like perhaps only Friedrich Nietzsche in the modern age, Weil “fully inhabited her philosophy.” In search of truth through action, she worked on fishing trawlers, farms, and in factories, fought alongside anarchists in the Spanish Civil War, and joined the Free French in London in 1942.

Unlike Nietzsche, however, Weil identified as a slave, and, for that reason, converted in the late 1930s from communism (with a small “c”) to Christianity. To be sure, Weil was embarrassed by the institution of the Church. Nonetheless, she grew to love the Catholic faith, God, Christ, and the saints. She was often described as a saint herself, and as Robert Zaretsky perceptively suggests in his excellent new monograph on the anomalous French thinker, it was this quality which made her not only noble but also somewhat inhuman, unbending in her commitments to the point of ruthlessness.

Dubbed the “Red Virgin” by the director of the ENS, Weil undoubtedly had something of the femcel about her, and was forever struggling to form meaningful connections with others. Politically, she became a fanatical proponent of moderation, denouncing Communism as vehemently as she did fascism. Her own idealism, however, was pointedly excessive. Referred to as “Antigone” by her family, from a young age Weil revealed an “immoderate attachment to acting on her convictions.” At the age of five, she gave up eating sugar as an act of solidarity with French soldiers at the front. At 34, she refused to eat more calories than her fellow citizens in occupied France.

There was certainly a child-like quality to Weil—if not entirely innocent, then arrogant at least. Despite her best efforts to achieve philosophical worldliness, Weil was a thinker unfamiliar with the complex negotiations and compromises of a full and connected life. That said, once one gets past the immaturity that moderately marks her work, we encounter a profound philosopher and great soul who speaks directly to issues we confront today.

Resisting the understandable temptation to psychoanalyse, Zaretsky’s pithy book instead explores a number of “core themes” in Weil’s thought that continue to resonate. Its five chapters are devoted, respectively, to Weil’s views on affliction, attention, resistance, rootedness, and goodness. Wearing his erudition lightly, Zaretsky is a brilliant guide to the ideas of his ever-paradoxical subject. For instance, alongside Weil’s idealism, we learn of her realism—an insistence on the omnipresence of power. Never a Marxist, but impressed for a time by Marx’s analysis of capitalism, by 1934 Weil had repudiated her youthful revolutionary syndicalism. It was simply in the nature of things, she concluded, that both Communism and syndicalism would eventually lead to oppression. For Weil, oppression is constant, whatever social organisation obtains.

Chastising the followers of Marx for ignoring workers’ actual experiences, Weil was almost a nominalist, and she awaited insights, as opposed to going in search of them. Eschewing as far as possible preconceived categories like “base and superstructure” and “proletariat” and “bourgeoisie,” she adopted a receptive and non-judgemental approach to life and learning. Truth “is always a truth about something,” she insisted, and must be rescued from mere speculation. Not always consistent in her empiricism, she also believed in “a God who in love withdraws from us so that we can love him.” Her notion of decreation involved what Iris Murdoch, a great admirer of Weil, re-termed “unselfing,” the process of surrendering oneself to a transcendental Good.

In an age of renewed yet equally vacuous idealism, diminishing attention spans, and generalised narcissism, Zaretsky’s careful reconstruction of Weil’s thought on these themes is worthwhile and important. But above all, what makes The Subversive Simone Weil such a solid triumph are the comparisons the author draws between Weil and other thinkers. As a comparative analyst, Zaretsky’s performance is virtuoso—among those discussed are Olympe de Gouges, Johann Gottfried Herder, Martha Nussbaum, Charles Taylor, and Michael Sandel. There are four thinkers, however, that Weil resembled who ought to be mentioned here in more depth. For it is precisely the right company for the unclubbable French philosopher.

The first and most obvious was George Orwell. Near contemporaries, they both fought in Spain and abhorred totalitarianism. They both stressed the need to think and express oneself clearly. They both viewed pacifism in 1939 as “objectively pro-fascist.” And they both went Down and Out in Paris, so to speak. Indeed, it was as a factory employee that Weil discovered affliction, the alienated state in which one becomes subjugated to a machine or process and in which the act of thinking becomes impossible—where, in short, one becomes a slave. Orwell, likewise, made acquaintance with this alienated state among the Parisian plongeurs–“the ‘divers’ who spent their days and nights washing the pots and plates at the city’s restaurants.”

“Affliction,” wrote Weil, makes people pliant and therefore dangerous, and “constrains a man to ask continually ‘Why?’” As Zaretsky adroitly observes, Weil’s “idea of ‘collectivity’ resembles Hannah Arendt’s later notion of ‘thoughtlessness,’ the condition she associated with Adolf Eichmann.” Weil, like Arendt, understood that evil could be banal. Affliction was not the fate of all workers, however. In The Human Condition (1958), Arendt distinguished between labour and work—the former is the product of simple necessity, she argued, and the latter involves skill and thought. Weil likewise differentiated the mechanical task of an assembly-line worker from the skilled and intelligent work of, say, a fisherman who battled, unalienated, “against wind and waves in his little boat.”

Arendt, we learn, knew and valued Weil’s work. As did Albert Camus. And Zeretsky expertly establishes the influence of Weil on each thinker. For example, The Plague (1947) turns out to be a Weilian text. So, too, is its philosophical companion, The Rebel (1951). The distinction between rebellion and revolution is drawn directly from Weil, and just as Weil asserted that there “exists an obligation towards every human being for the sole reason that he or she is a human being,” Camus’s rebel, while oppressed, does not dehumanise and mistreat the oppressor. Camus, Orwell, Arendt, and Weil were all political outsiders and counselled moderation. Renouncing revolution as impetuous and wrong-headed, Weil believed that resistance began with clarity of thought and ended with what we might reasonably expect, not everything we wished for.

In this respect, Zaretsky argues, Weil espoused “a fundamentally conservative conception of revolution and resistance.” But her conservatism did not end there—her wartime book, The Need for Roots, was “both more radical and more conservative” than ever. She shared much in common, in fact, with the father of philosophical conservatism Edmund Burke. Above all, they both stressed the ontological importance of rootedness. Without roots we are nothing. Embracing an organicism intrinsic to conservative thought, Weil averred that there could be no self without society. She lamented the disconnectedness ushered in by modernity and capitalism, where community counts for little, the past counts for less, and the future is rarely considered at all.

Wary of abstract reason (“the great human error is to reason in place of finding out”), Weil was a particularist. She believed in conserving what was exceptional or merely unique in a nation’s heritage. If Burke espoused a compassionate conservatism, Weil espoused a compassionate patriotism. Rejecting pride as a foundation for love of country, she nevertheless maintained that there is nothing inherently wrong with patriotism itself. Quite the opposite—“A perfectly pure love for one’s country,” she wrote, “bears a close resemblance to the feelings which his young children, his aged parents, or a beloved wife inspire in a man.” The right kind of patriotism is both healthy and deeply felt at the level of human need. In its absence we are uprooted and unwell.

Weil, of course, was never dewy-eyed about her own country’s past or present. But that did not prevent her from striking a balance between morality and reality. To have a nation is essential, she thought, even if it is flawed and guilty of past transgressions. Just because France possessed an empire which perniciously uprooted others, that did not mean it was unworthy of its citizens’ attachment. It was not, however, as a guardian of its citizens’ rights that a nation deserved respect, it was due to the obligations citizens owed one another, and to the history they shared. These are lessons that liberals would do well to learn. We must learn to love our countries. And we must learn to assume our obligations as well as proclaim our rights.

In 1943, Weil sought to put these principles into practice: on one hand, at the very moment when de Gaulle was attempting to rally the support of French colonial leaders, Weil berated France for its role as a colonial power; on the other, Weil proposed her “Nurses Plan,” a scheme to parachute white uniformed nurses into battle in occupied France, with Weil leading the first group herself. This suggestion was absurdly impractical and dismissed without consideration. But it is not for common sense or everyday political nous that we turn to Weil. It is for purity and profundity and goodness. In presenting her ideas to readers unfamiliar with her remarkable work, Zaretsky has performed a service of incalculable value. Moreover, he has done so with style and insight and grace. The Subversive Simone Weil is a magnificent introduction to an extraordinary set of ideas.