Gender Activists Co-Opted British Columbia’s Courts. Meet the Woman Who Stood Up to Them

Under this policy, declaring one’s pronouns is required when people introduce themselves in court whether they present in keeping with their biological sex or not.

We have become so habituated to acts of deplatforming that many of us can no longer keep up: Though each new incident still elicits a ritual sigh of regret, we increasingly shrug it off as just another sign of these crazy times. Yet many of these episodes signify important injustices that deserve our attention. The recent deplatforming of British Columbia lawyer Shahdin Farsai falls into that category.

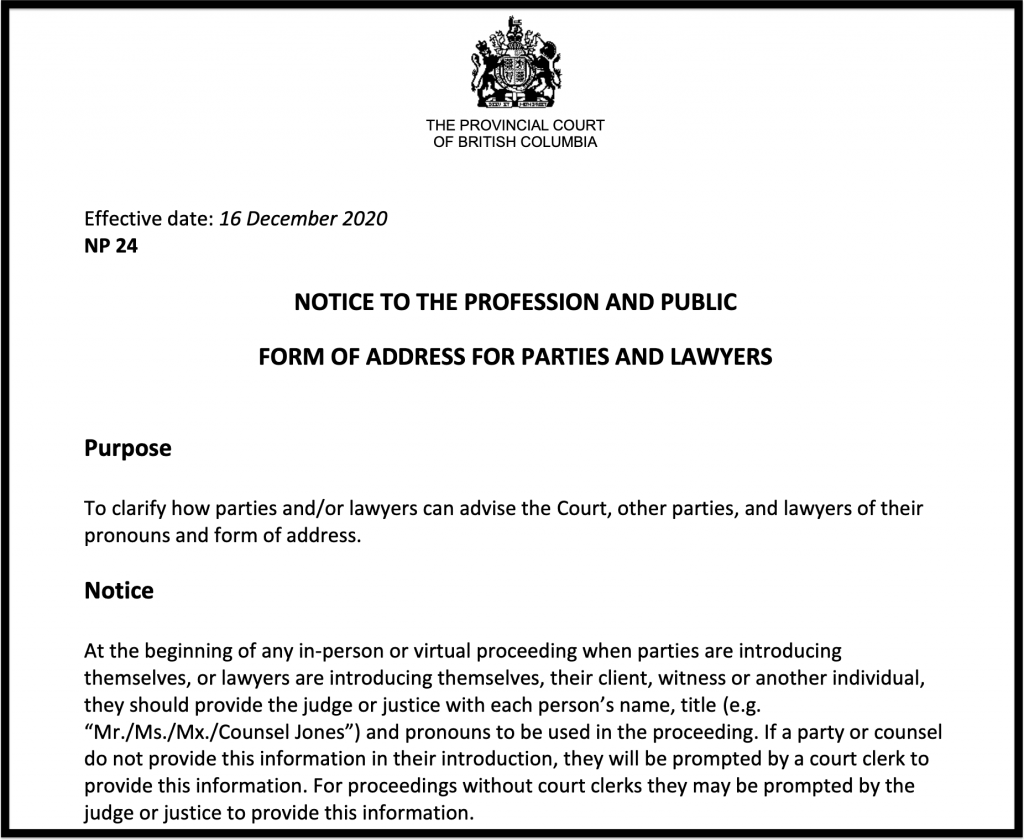

The back story begins on December 16th, 2020, when the B.C. Provincial Court issued an announcement advising lawyers and the public of a new practice directive stipulating that all parties appearing in court would henceforth be asked to specify what pronouns they want others to use when referring to them, as well as their preferred forms of address. (Examples provided are “Mr./Ms./Mx./Counsel Jones.”) The Chief Justice of the B.C. Supreme Court issued a similar practice directive on the same day, though without a press release.

“Using incorrect gendered language for a party or lawyer in court can cause uncomfortable tension and distract them from the proceedings that all participants should be free to concentrate on,” the Provincial Court announcement stated. “The Court hopes its new Notice will contribute to a culture that is inclusive and respectful of everyone.”

The declared intent was to accommodate “gender diverse” parties and lawyers. But the term “gender” is not used here in the traditional sense of including both men and women. Rather, the idea is to accommodate the belief that gender is a matter of self-identification, and that it exists on an infinite spectrum that supersedes scientifically observable principles of biology. In its doctrinaire formulation, this belief is sometimes described as gender ideology.

Under this policy, declaring one’s pronouns is required when people introduce themselves in court whether they present in keeping with their biological sex or not. The directives specify that anyone who does not say “my pronouns are…” “will be prompted by a court clerk” to do so; or, “for proceedings without court clerks, they may be prompted by the judge or justice to provide this information.”

The announcement did not indicate what would happen if the prompting was ignored or rebuffed. It also did not expand on the obvious expectation that the specified pronouns would be used by others in court throughout subsequent proceedings, no matter how unusual those chosen pronouns might be, nor (as discussed below) how such a policy may indirectly compromise the administration of justice.

Although this announcement was presented as compelling “inclusive” behaviour, the B.C. bar as a whole had not been asked for input. The court’s announcement indicated only one particular group of lawyers that had been involved, namely those belonging to the Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Committee (SOGIC) section of the Canadian Bar Association, B.C. Branch—which presents itself as seeking “to address the needs and concerns of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and two-spirited people.” (the contested term “Two-spirit” refers to some Indigenous individuals who describe themselves as having both masculine and feminine spirits). The court even thanked the SOGIC section for its members’ “helpful feedback on this new notice.”

But the follow-up news coverage revealed that the SOGIC had done more than simply provide feedback. The committee had pushed actively for such policy changes; and provided guidance to the B.C. courts for the new rules. SOGIC co-chair Lisa Nevens personally “helped provide input to the courts for the changes,” according to the Vancouver Sun. And Canadian Lawyer magazine reported that the court “developed the policy with the help of the executive of [SOGIC].”

In fact, Nevens basically acted as the media point person for the courts’ announcement. (From what I can tell, there were no media interviews with any judges.) As seen by the general public, and even other lawyers, SOGIC effectively has become the public-relations arm of the judiciary on this issue.

And Nevens seems to have more ambitious plans, having expressed hope that the new requirements will be, as CTV News reported, “picked up by B.C.’s administrative tribunals, such as the Human Rights Tribunal” (this being the body that the trans-identified serial litigant known as Jessica Yaniv/Simpson used as an attempted means to extort money from female aestheticians who refused to handle Jessica’s scrotum and penis several years ago). Nevens also believes “the courts still have more work to do,” such as getting rid of “my Lord” and “my Lady” titles—a project that Nevens is now pursuing.

While Canadian Bar Association sections are typically focussed on building expertise within substantive areas of law, the SOGIC always has assumed a more activist stance. It was founded in 2009, four years after the fight for gay marriage was won in Canada. And so, like similar organizations, its focus has increasingly drifted toward transgenderism. The group now formally describes itself as promoting the interests of “LGBTQ2SI+”—indicating Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer or Questioning, Two-Spirit, Intersex, and (as signified by the “+” symbol) additional unspecified orientations and gender variants.

In keeping with Canadian cultural trends, members of the group also find ways to intermingle their ideas about gender with seemingly unrelated ideas about anti-racism and decolonization. Adrienne Smith, who recently addressed the SOGIC on the issue of “Trans Competent Lawyering,” for instance, argues that “before colonizers came to this part of Turtle Island [i.e., Canada] in their genocidal crusade … there had been nations [where] there was lots of ways of being in the world; not a binary gender everywhere. And then we came, and … I’m responsible for this genocidal legacy … and we cut all the boy’s hair and we put all the girls in dresses and we imposed a very binary way of being. Two-spirit people … are folks who had [a] masculine and feminine spirit in the same body and we obliterated that.”

While such ideas may seem obscure, the SOGIC has made itself extremely influential, despite having just over 200 members. A recent article published by Canadian Lawyer indicated that even some judges now belong to the group, which raises questions about judicial independence. (To my knowledge, the membership list isn’t public.)

On January 27th, the Chief Justice of the B.C. Provincial Court, Melissa Gillespie, conducted a webinar for B.C. law students in which she confirmed that the SOGIC had taken the lead in the creation of the new pronoun policy. When pushed on the implications of the directives, she suggested that concerned parties take their questions to the SOGIC itself. She also assured everyone that the initiative “was meant in only the best and most inclusive way.”

Yet the definition of “best and most inclusive” seems to be changing with the seasons. Less than two years ago, the B.C. Court of Appeal issued a new practice directive for appearing before the Court that did not require pronouns (though it did specify Mr., Ms., or Mx., as options). That directive replaced a 2014 version that didn’t specify forms of address at all.

Moreover, these developments are taking place amidst a larger shift within B.C. legal culture that substantively affects the manner in which laws are interpreted and applied. In several recent cases I am aware of, B.C. judges have allowed tenets of gender ideology—including the idea that self-declaration as a man or woman serves to erase the real ways in which one’s body affects others in intimate spaces—as unassailable fact. On more than one occasion, a judge has used male pronouns to refer to girls whose proposed sex change was itself the issue under review. Why have a judicial proceeding at all if a judge’s very language indicates that the outcome has already been decided?

Some of the lawyers acting for the parties favouring sex change for these girls were affiliated with the SOGIC in some way. Two of the province’s three chief justices, Chief Justice Christopher Hinkson of the B.C. Supreme Court and Chief Justice Robert Bauman of the B.C. Court of Appeal, were involved in hearing these cases. The new practice directives were enacted while these cases were underway in their respective courts. The fact that all of these cases (to my knowledge) were decided in favour of children transitioning against their parents’ wishes raises questions of whether courts are being co-opted by an ideological movement whose dictates now serve to trump traditional principles of law.

As many readers know, raising one’s voice against these trends can be difficult, because those who do so are tarred as transphobic. But some people, including the woman I discuss in the paragraphs below, now feel compelled to speak up as a means to protect against male encroachment on female spaces (including prisons, shelters, and sports) and to protect children from dangerous medical treatments. Often, we are described as “gender critical” in our approach. Internet trolls call us “TERFs.” But in general, we are simply voicing common sense—including in the legal sphere.

On the surface, Shahdin Farsai may seem like an unlikely target for a progressive mob. She’s a young Iranian-Canadian lawyer whose B.C.-based practice has focused on dispute resolution and estate planning. Before joining a law firm, she clerked at the B.C. Supreme Court and obtained a master’s degree in Public Policy. Her law degree came with cum laude honours. Farsai also happens to be a woman, and one who’s taken seriously all of the messaging we’ve heard in recent years about how women need to make their voices heard in historically male-dominated professions.

To Farsai, the new directives from the B.C. courts represented a form of compelled speech—and not just in a nominal sense. Reciting one’s pronouns may seem like a mere courtesy, and no doubt, many people who do so intend it as such. But it also has a political and ideological connotation, as the ritual is meant to suggest that one’s biologically rooted (and outwardly observable) identity can be altered by declaration, and that everyone must accede to that self-identification, even in contexts where the interests of others are thereby affected.

In mid-January, Farsai’s article opposing the courts’ new policy was accepted by the Advocate, which is published by the Vancouver Bar Association and funded with fees collected from lawyers through the Law Society of B.C. Farsai’s essay was not a generalized rant against trans people (as critics would later claim), but a well-informed critique of a policy that, as Farsai persuasively argued, may serve to compromise a client’s legal interests in cases involving family law or alleged sexual assault:

[Lawyers] must not be under any obligation to refer to another party by their preferred pronouns, especially if doing so would go against the legal position and the instructions that they receive from their clients. This point was made in a recent case before the B.C. Supreme Court. The court heard the case of a mother attempting to prevent her 17-year-old daughter from having surgery to remove her breasts. The daughter wanted to transition to the male gender, and provincial authorities supported her wish. The mother still regarded her daughter as a female. The question of her gender transition was the very issue before the court. Yet when the mother and her counsel referred to the daughter as “her,” the judge challenged the mother’s right to do so. According to the transcript, the judge said, “there has been a request that counsel refer to [the youth] as he or him … are you refusing to do that?” … I turn to a UK example to illustrate the point. In the UK, they have a similar pronoun practice direction. Recently, a complainant of an assault was repeatedly told by a judge to refer to her assailant using the female pronouns, when he was, in fact, a biological male. The judge is reported to have described the complainant´s pronoun infractions as “bad grace” when explaining his reasons for not awarding her financial compensation for the assault (although he could have done so). Sadly, the court compelled her to describe her evidence under oath in a way that hid reality instead of revealing the truth and to add insult to injury she was denied rightful legal compensation. My worry is that such a development could occur in B.C. given the new directive.

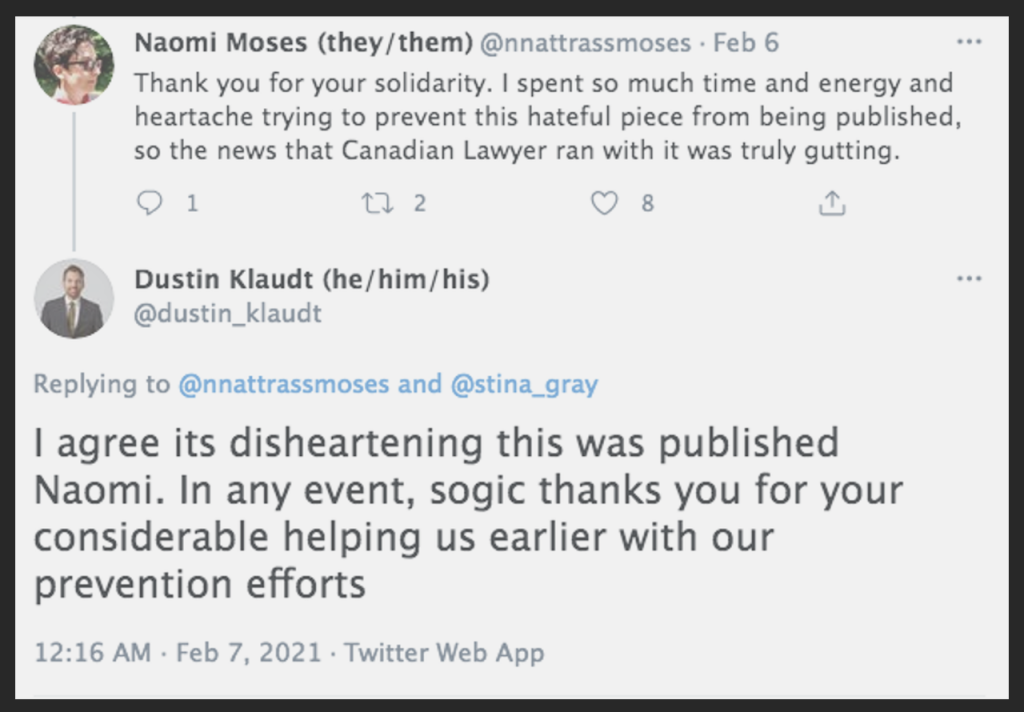

The editor of the Advocate also sought a rebuttal from members of the SOGIC, to publish alongside Farsai’s article. But when the Advocate’s request was received by committee co-chair Dustin Klaudt, he apparently became more interested in blocking Farsai’s piece than in rebutting it.

It emerged in due course that SOGIC members allegedly threatened the Advocate with legal action, and raised the idea that the publication’s funding could be at stake, if they published Farsai’s piece. The journal’s editor, Michael Bain, described all this in an editorial published in the Advocate’s March issue:

As a result of our effort to be fair to members of the legal profession with competing views, word of our inquiry [to SOGIC] leaked and we were rather dramatically cautioned that what the Advocate published on the matter could result in a human rights complaint against us. We have also been advised that this is not a topic that is open to debate and that criticism of the [court] directions may amount to hate speech … It [also] has been hinted that funding for the Advocate may be at risk if we publish views contrary to those of the Law Society, though we emphasize that this threat has not come from the Law Society itself.

There are many startling aspects to this, none more so than the fact that SOGIC members now apparently conceive of themselves as speaking, at least implicitly, with the moral authority of the entire provincial bar.

Among the objections Bain received to Farsai’s (then unpublished) piece was an email from the aforementioned Adrienne Smith, who is described by the SOGIC as “the leading [gender] educator in this area within B.C.’s legal community.” Smith called the article “hateful, inflammatory, and wrong at law.” Smith also suggested that publication “would expose the Advocate to liability (or at least notoriety) in a human rights complaint for hateful publications.” SOGIC founder Barbara Findlay personally telephoned Bain, “strongly encouraging” him not to publish the Farsai piece, and giving him “further case law citations to consider.”

Findlay speaks with some authority on these pressure tactics. In a 2016 seminar at the University of British Columbia, she told audience members:

Well, speaking as an organizer, the way—I mean, what I do is I file a human rights complaint. And I say, “Those regulations are deficient because … the omission of those kinds of things contravenes the Human Rights Code.” I do that without particular regard for whether ultimately I will be successful, because it’s an excellent pressure tool … And so then you’re armed with something more than your opinion. You’re armed with a legal duty. You say, “Don’t we have a legal duty to do this?” Yes, we do.

In the case of the Advocate, as it turned out, these tactics were successful: The editor was intimidated into killing Farsai’s piece.

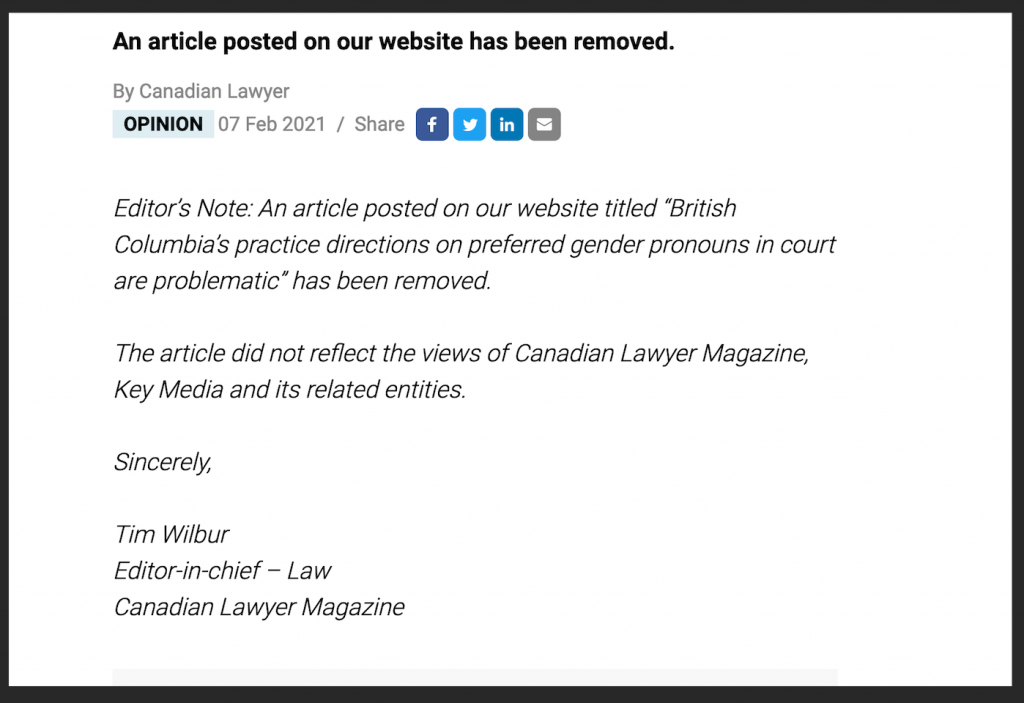

Farsai was then able to publish a condensed version of the piece with Canadian Lawyer, a national trade publication. The article appeared on the magazine’s site on February 5, 2021. But of course, this is not where the story ends.

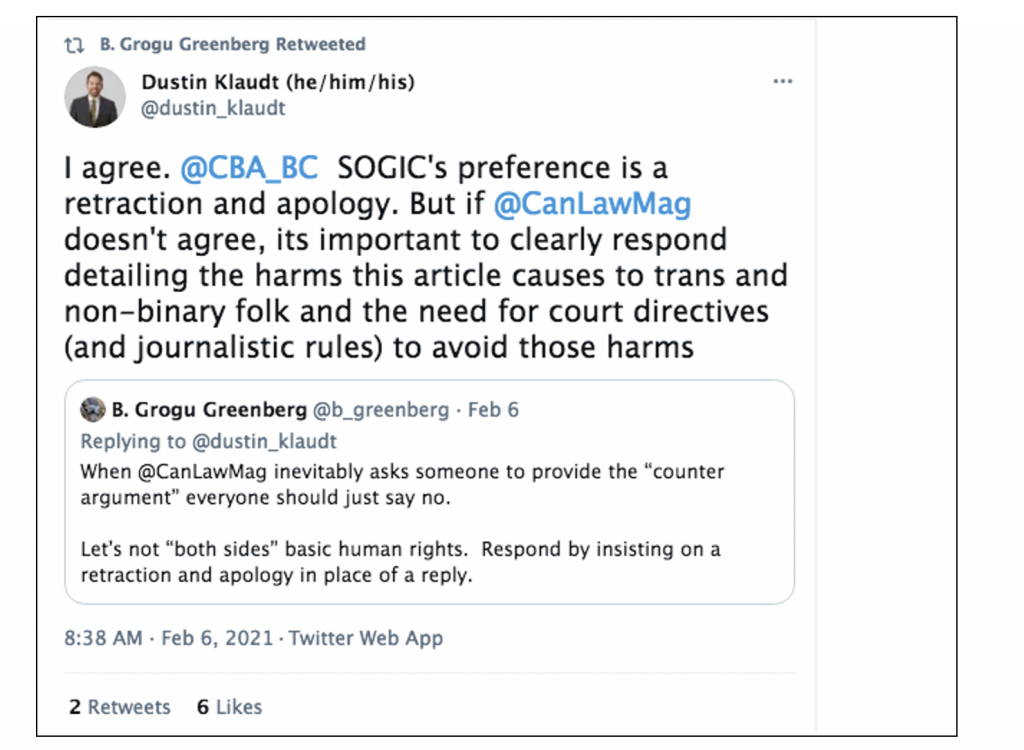

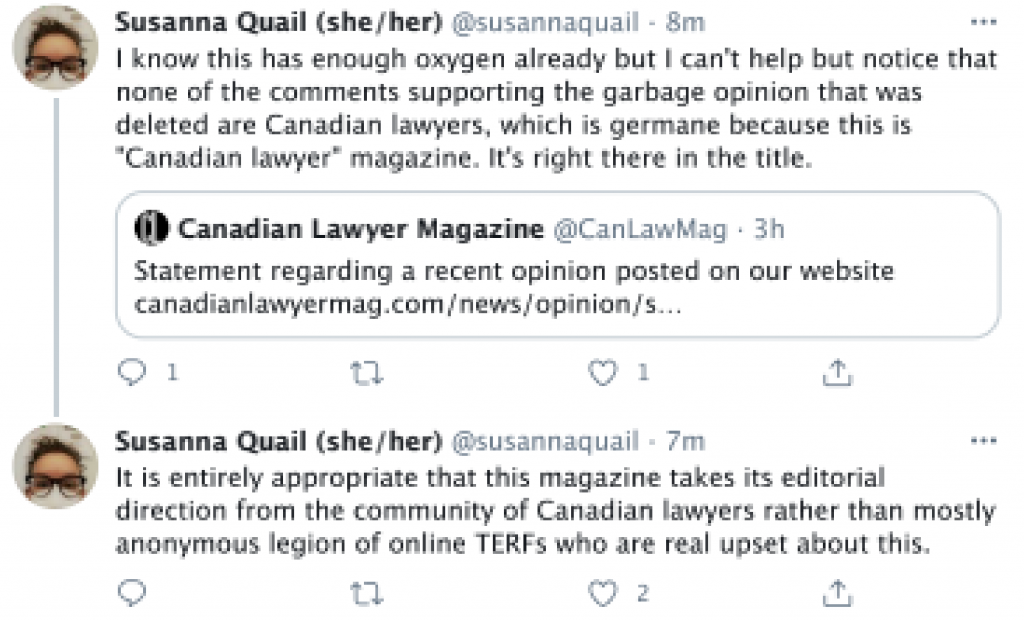

Prior to publishing Farsai’s article, Canadian Lawyer had published various pieces supporting trans rights, including one that ran just three days before Farsai’s piece appeared. But one of the signature talking points of SOGIC and similar groups is that this isn’t an issue on which reasonable people can differ: There is no room for debate, in their view, since any deviation from the orthodox position is simply an expression of hate dressed up as free speech. Following a co-ordinated SOGIC mob campaign, Canadian Lawyer removed Farsai’s piece about 36 hours after its publication. And a note of abject apology now sits at the URL where the article once ran.

You can still read Farsai’s article, which was republished at Canadian Gender Report, a popular advocacy site featuring gender-critical news. But that didn’t seem to concern SOGIC members—because their real purpose wasn’t to suppress Farsai entirely (which they recognize as impossible), but rather to demonstrate that they can dictate the scope of acceptable positions within their own field’s professional and media organs. The Advocate and Canadian Lawyer sit within this legal subculture. Canadian Gender Report does not.

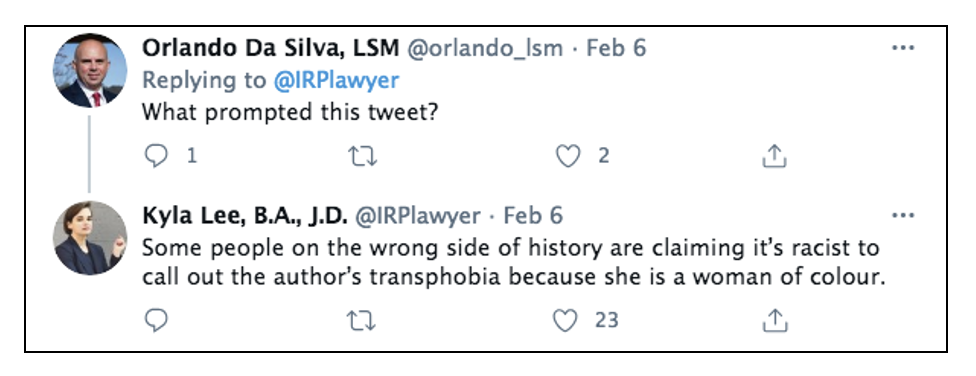

The details of Farsai’s online mobbing are, in many ways, exactly what you would expect: There were personal insults, intellectually dishonest denigration of the article’s content, and, of course, an attempt to get at Farsai through her employer. This being a controversy connected to trans rights, there was also the predictably grotesque lie that Farsai, and anyone agreeing with her, was “literally questioning our [meaning trans people’s] right to exist.” Except that these weren’t random Twitter users attacking this woman. They were lawyers—people trained to argue both sides of any case, even cases involving the most abhorrent criminals.

These lawyers included Law Society of B.C. bencher Brook Greenberg. (In Canadian law societies, benchers typically establish a group’s rules and policies, and oversee any programs carried out by the society.) Dustin Klaudt, SOGIC co-chair, said the committee wanted a retraction and apology, and claimed the article’s mere existence caused “harms” to “trans and non-binary folk.” He also said that the case showed the need for (unspecified) “journalistic rules” that would serve to prevent the publication of such viewpoints.

Frances Mahon, co-chair of the national CBA SOGIC, picked up on the idea that there weren’t really two sides to this issue, but rather one legitimate side that is besieged by transphobic haters. Indeed, this lawyer declared she would not even take the trouble to “formulat[e] an intelligent response” to Farsai because it was a Saturday, and she was too busy. An hour and 20 minutes later, however, her schedule apparently freed up, and Mahon announced what she described as a “lawyers’ strike from Canadian Lawyer.”

Mahon’s manifesto eventually attracted more than 200 signatures from individuals who threatened to “decline any requests to write articles, provide quotes, or otherwise contribute to Canadian Lawyer” unless the magazine agreed to the humiliation of Farsai. (Signatories included three benchers of the Law Society of B.C.: Brook Greenberg, Jamie Maclaren, and Kevin Westell.) But what the magazine’s owners likely feared more was a loss of advertising from woke law firms.

I won’t get into all the details of the protracted flame war that played out on Twitter in the days that followed. But it was interesting to observe that while the aforementioned SOGIC members and supporters were performatively high-fiving each other for forcing Canadian Lawyer to erase an article they disliked, many of them also seemed surprised and stung by the high-volume backlash among members of the general public—including those who noted that this largely white group of privileged diversity champions was ganging up on an Iranian-Canadian woman.

In some cases, the SOGIC crowd became so flustered by the ratios on some Tweets that they attacked the idea that non-lawyers should even be permitted to offer their opinions on such subjects—an oddly snobbish view (as more than a few tweeters were happy to point out) for activists claiming to be working for “inclusivity.”

One way in which this controversy is different from other mobbings is that the target hasn’t had her life ruined—largely because her employer stood by her, and because she is not the type of person to let herself be intimidated. Even so, the SOGIC crowd succeeded in demonstrating their complete ideological control of B.C.’s legal industry, and even the national trade media—despite the fact that SOGIC’s membership comprises less than two percent of B.C.’s approximately 12,000 lawyers. As in 2020, the professional development calendar for the province’s lawyers is now full of accredited trans-focused lawyering sessions, with titles like Trans/forming the Queer Legal Landscape, and Don’t Guess, Just Ask—Pronouns in Practice.

It’s a classic collective action problem, and one that we have seen in other sectors: While many lawyers roll their eyes at this type of indoctrination, few care enough about it to raise their voices. And so the field has been left to the minority of single-issue activists who care a great deal. Even those who might have been inclined to stick their necks out can only be chastened by the treatment Farsai received. Lawyers tend to be busy people. And few will go to the trouble of asserting their principles when it’s so much easier to simply give in and recite your pronouns.

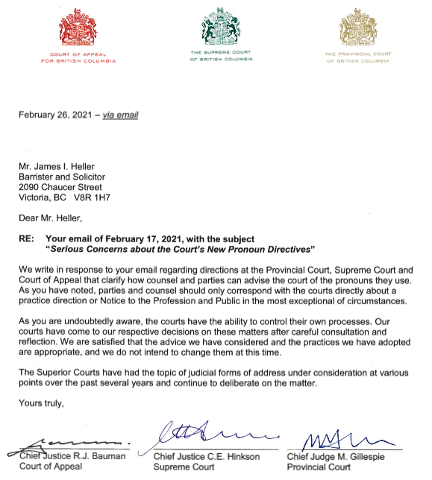

One of those few individuals is Victoria lawyer Jim Heller, who recently wrote directly to the province’s chief judges about the issue. His letter is worth quoting at some length. The court system’s new policy, he said:

is not simply a request that lawyers accommodate the wishes of transgendered people to be addressed uniquely. Rather, it demands that we all now accept the proposition that one cannot assume to know how to refer to others based solely on their “name, appearance or voice” … I and many others disagree with this assertion and in fact consider it provocative and ideological. At minimum, we believe that such a controversial directive should have been thoroughly canvassed with the bar rather than unilaterally mandated. I appreciate that the judiciary were persuaded to wade into these waters with the best of intentions. However, by acting on the counsel of one single advocacy group and not consulting with the bar as a whole, all the members of which are obviously stakeholders on the issue of how we present ourselves, the courts have unwittingly caused more confusion—indeed discomfort—than they hoped to ameliorate … If, then, the judiciary still believes that this is a pressing social concern that must be addressed, let us as a community discuss it together. Whatever embarrassment or confusion a reversal now might cause would, in my view, be nothing in comparison to the erosion of respect for the administration of justice in the long-term.

Responding to Heller, the judges proclaimed themselves to be content with their advisers and their decision. And various legal organizations have taken the hint by proactively listing their staff members’ pronouns on their websites. Whether this is being done as a good-faith bid to signal support for universal pronoun declarations, or they are seeking to ingratiate themselves with the province’s judicial establishment, or they simply want to ensure they’re not in the cross-hairs of the province’s legal cancel mobs, it’s hard to say. This is a movement that dresses itself up in rainbows and glitter. But as the treatment of Farsai shows, what it’s really about is using the levers of institutional power to force the rest of us to fake a belief in an idea that biology keeps reminding us isn’t really true.