Activism

Houses of Horrors

In some former British colonies, confronting the dispossession and murder of native peoples has prompted efforts at apology and restitution.

In country after country, museums are now undergoing an épuration—a process of confession and penance. Until recently, debate about empire in European and other democratic countries was consigned to historians’ squabbles. Now, the West’s colonial past occupies a central place in the culture wars, roaring for belated recognition of its legacies. At the least, the demand now pressed upon the museums, mainly by their own radicalised staffs, is for greater sensitivity and respect in the display of the millions of artefacts taken from colonial possessions. At the most morally exacting extreme, they are exhorted to adopt a similar posture to that taken by Holocaust museums, acknowledging complicity in organised massacres.

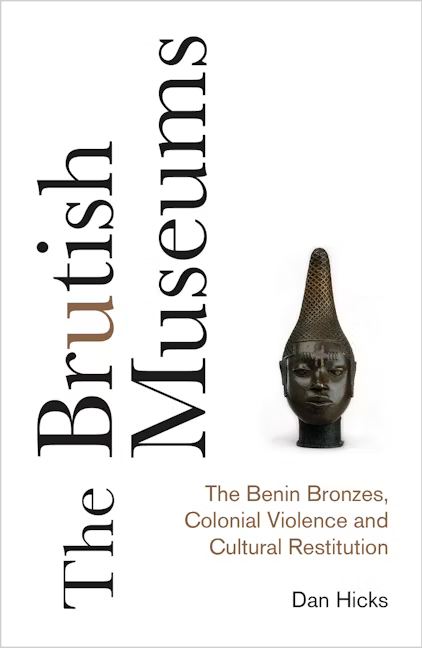

On this account, museums must bear witness to past events “where people are killed in their thousands and tens of thousands, when palaces, temples and villages are bombarded, when cultural treasures are looted and sold.” This is the uncompromising posture adopted by Dan Hicks, Professor of Contemporary Archaeology at Oxford University, curator of archaeology at the university’s Pitt Rivers Museum, and author of The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution. Hicks demands penitential obeisance before Europe’s monstrous crimes against humanity resembling that displayed by German Chancellor Willy Brandt’s when he visited the Warsaw ghetto in December 1970.

This requires a painful confrontation with Europe’s imperial past, which began in the early modern period—the late-15th century—with the Spanish and Portuguese colonial occupations and lasted until the often bloody withdrawals after World War Two. A heavy burden of white guilt has been compiled and a new generation of curators and academics are now turning the tables on their seniors—we are the masters now, they declare, we grasp how rotten was the past, how deeply it has infected white people with racism, and how cauterising must be the cure.

Everywhere, museums have been swept into this ideological maelstrom, and an issue hitherto debated on specialist websites and arts pages is now the stuff of fierce political disputation. In some former British colonies, confronting the dispossession and murder of native peoples has prompted efforts at apology and restitution. But these have been fiercely contested by those who see such initiatives as the unnecessary and self indulgent scratching of old wounds which time, not breast-beating, will heal.

In the Netherlands, Margriet Schavemaker, the artistic director of Amsterdam’s Portrait Gallery of the Golden Age, wants to rename the institution to avoid romanticising Dutch colonialism. Her intention was greeted with a flood of protests and dismissed by Prime Minister Mark Rutte—recently elected to a fourth term of office—as “nonsense.”

A 2017 pledge by Lisbon’s socialist mayor, Fernando Medina, to develop a Museum of Discoveries framing a Portuguese “golden age” of worldwide exploration ran into a similar storm, with intellectuals denouncing it as neo-imperialism and others objecting to a proposed section on the evils of slavery. Publico columnist João André Costa took the mayor’s side, writing that “we don’t have anything to beat ourselves up about, kneeling for 100 years with downcast eyes and hearts.”

In 2017, Austria’s Ethnology Museum in Vienna began a series of exhibitions (in the former Hofburg Imperial Palace, ironically) inviting discussion on the way in which the museum’s articles had been collected. One room is reserved for the display of the famed Benin bronzes, intricate statues and plaques dating from the 13th century onwards which had been taken from Benin City (now in Nigeria) after a British Army force razed it in 1897. The British Museum got 200 of the bronzes and the rest went to museums in Europe and private collections. The Nigerian authorities want them back. Indeed, a museum is to be designed in an excavated Benin City by the British-Nigerian architect Sir David Adjaye, where the bronzes will be displayed when—or if—the present owners return them. Sir David told the New York Times in November that the purpose of the museum is “to deal with the real elephant in the room, which is the impact of colonialism on the cultures of Africa.”

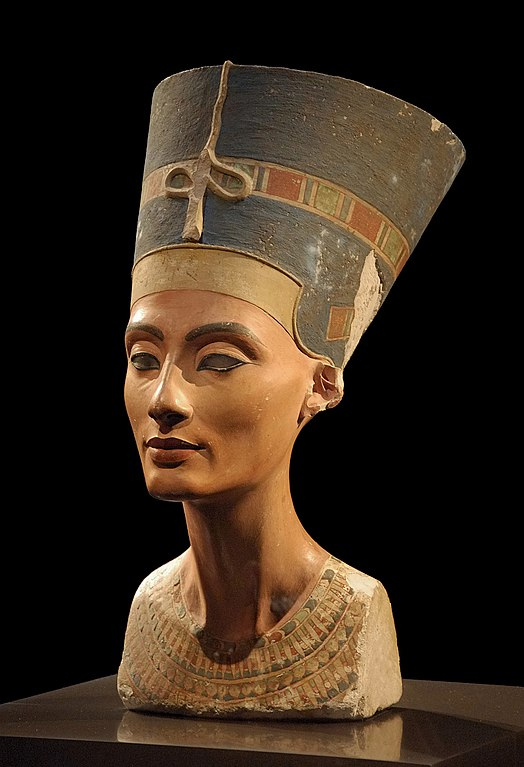

A new exhibition space opening this year in Berlin’s Humboldt Forum has been roiled by accusations that the ethnology exhibits were chosen for their assumed popularity without due consideration of their provenance. Besides more of the Benin bronzes, the museum will display a famed bust of Nefertiti, wife of the Pharaoh Akhenaten (1350s–1330s BCE), discovered during the 1912 excavation of royal sculptor Thutmose’s studio by German archaeologists. Its radiance is certain to attract a crowd. The Egyptian authorities say it was not declared to their predecessors when it was taken out of the country and now they want it back.

The Forum is to be housed in a reconstructed royal palace, reduced to a shell during the war. Many objected to that decision, too. In May, a new controversy flared when a 17-tonne dome, topped with a large cross, was hoisted onto the palace. A band running around the circumference displays text from the 19th century King Friedrich William IV, calling on all peoples to “bow down on their knees” to the Christian god. This prompted the Frankfurt-based curator Mahret Kupka to say in an interview that “Christianity has been a channel through which colonialism functioned, and was strengthened.” Social media buzzed with agreement.

The most dramatic of the protests came from a French art historian, Bénédicte Savoy, who compared the creation of the Humboldt Forum to the Ukrainian nuclear power plant in Chernobyl which melted down in April 1986. Savoy resigned from the board of experts advising on the Forum’s creation because, she said, its members were uninterested in the history of the exhibits’ acquisition. In 2018, Savoy had co-authored a report with a Senegalese-born academic Felwine Sarr on the colonial objects held in French museums and the scope for restitution. This followed a speech French President Emmanuel Macron gave at the University of Ouagadougou in Burkina Faso in November 2017. Europe’s colonisation of Africa, Macron said, had been “a crime against humanity… in the next five years, I want the conditions to be met for the temporary or permanent restitution of African heritage to Africa.”

Sarr and Savoy were merciless on the greed of the European conquerors:

In China (1860), in Korea (1866), in Ethiopia (1868), in the Asante Kingdom (1874), in Cameroon (1884), in the Tanganyika lake region, and the future Belgian Congo (1884), in the current region of Mali (1890), at Dahomey (1892), in the Kingdom of Benin (1897), in present-day Guinea (1898), in Indonesia (1906), in Tanzania (1907), the military raids and so-called punitive expeditions conducted by England (i.e. Britain), Belgium, Germany, Holland, and France, during the 19th century became occasions for unprecedented pillaging and acquisition of objects of cultural heritage.

The report called for more than restitution. The authors want the looted pieces to nurture new relationships—political, cultural, and human—between France (and by implication the other former imperialists too) and their former colonies: “a new relation(ship)… based on a mutual recognition of our interdependence.”

Many of the greatest British museums are either 19th century creations, or were founded in the late-18th century as “cabinets of curiosities” and hugely expanded in the 1800s. All display at least a few colonial pieces. Some—most famously the British Museum—are now in the coils of arguments about how they obtained their collections. The Museum’s Elgin Marbles from Athens’ Parthenon were bought by Lord Elgin, ambassador to the Ottoman Empire which then ruled Greece, and taken to London during the early 19th century. Greece has asked for them to be returned for decades.

Directors of museums now tend to sign up, at least in part, to postcolonial ideology. There are a few public conservatives who dissent, most notably Stéphane Martin, long-serving director of the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris, which contains over two-thirds of the 90,000 African pieces on display in French museums. Martin sternly criticised the decolonising report produced for President Macron, deploring that it held restitution to be more important than the heritage and present cultural contribution of the museums.

The largest imperial ethnographic collection in the world is housed in the Pitt Rivers Museum, an institute within Oxford University, where Dan Hicks is a curator. Inspired by his polemics, the Rhodes Must Fall campaign—which calls for the removal of the statue of 19th century imperialist Cecil Rhodes from a niche in Oriel College—pronounced the Pitt Rivers “the most violent place in Oxford.”

The striking and energetic woman in charge of this most violent place is the Belgian-born, Dutch-educated ethnographer Dr Laura Van Broekhoven. Some 600,000 objects are under her care, laid out in rows and rows of wood and glass cabinets. She has grasped the anti-colonial imperative: “I wasn’t surprised by the [‘violent place’] comment. The museum is a celebration of coloniality.” But she’s also aware of the task’s immensity: “A lot of work of change was going on behind the scenes: but the image of the Pitt Rivers had not changed—this is a Victorian building and institution—more or less as it was.”

The museum is named after the mid-19th century British General William Pitt-Rivers, a military expert in weaponry, with an active interest in ethnology and archaeology. He bequeathed to Oxford a collection of some 22,000 objects culled from many parts of the empire, and the university established the museum in his name as part of its Natural History Museum (they still share the same large, neo-Gothic building, a little way from Oxford’s centre).

“Change here is constant,” Van Broekhoven says, “taking place over many years, since Henry Balfour began his work as first curator in 1893. Quite soon Balfour developed the idea that they were looking at social evolution in the objects. It was an observation inspired by Darwin: they both saw evolution in this sense as going from savagery through barbarism to civilisation. In this progression, the General wanted to know if this could be seen through the objects themselves—objects like weapons, keys and locks, pipes, all manner of things.” Politely respectful of the founder, Van Broekhoven is nevertheless clear: “I don’t want us to remain with our current values and legacies: we are cutting away all of that. We will be updating the stories we tell.”

One story the Pitt Rivers used to tell was that of the shrunken heads, or tsantsa, of the Shuar and Achuar peoples of Ecuador, previously held in a cabinet labelled “Treatment of Dead Enemies.” These peoples, enemies of each other, decapitated, shrank, and preserved the heads of their defeated foes. Van Broekhoven issued a statement explaining the removal of the tsantsa, which says much about the nature of the changes many of these institutions are undergoing. She explained that they “led people to think in stereotypical and racist ways about Shuar culture. Standing in front of the case, people would talk about the people who had made them as ‘savage’ or ‘primitive’ and use words like ‘gory,’ ‘gruesome,’ or a ‘freak show’ when talking about the display. Shuar people have expressed dismay at their culture being represented in such ways…”

It is a decent action to address the dismay of the contemporary Shuar and Achuar people. It means, however, that the visitors who had enjoyed—as many did—a small uncomfortable shudder in front of the case are now represented as prone to stereotyped, and worse, racist thinking, on the slender evidence of the adjectives they were overheard using. The heads, consistently the most popular objects of the museum, are now in store, and dialogue with the Shuar and Achuar peoples’ representatives continue.

One of Van Broekhoven’s aides is a young scholar from the small Caribbean island state of St Lucia, Marenka Thompson-Odlum. Thompson-Odlum’s late uncle, George Odlum, had been Foreign Minister and Deputy Prime Minister and she completed a PhD at Glasgow University on the city’s trade in slaves. She is herself an activist, creating “slavery tours” in the city, replete with statues, mansions, tombs, and streets (such as Jamaica Street) which recall a colonial era that benefitted Glasgow’s economy. “I learned, however,” she says, “not to criticise David Livingstone,” the 19th century Scots working-class missionary explorer of Africa, still a pride of his nation.

Thompson-Odlum has been tasked with re-labelling the often ageing descriptions of the pieces but says, “The bigger problem remains—how do we reach out to all of these communities whose pieces are in here? We have to talk to the people who are the descendants. Of course they won’t necessarily be experts, but they will have embodied knowledge. If we go to, for example, Maori groups, we go to experts, yes, but we also need to find people who embody the knowledge of the communities. Part of the problem is that all cultures change and we have to find out how they do. We have to find out how the knowledge of a culture is reproduced. For example, a fire making ceremony—how do we reproduce the knowledge of that? People use the word ‘simple’ to describe it, but it’s not. In the Masai culture, fire is used as a binding ceremony.”

Like Broekhoven herself, she worries that, after the new broom, which she wields so energetically, has swept through the Pitt Rivers, “how do you re-integrate the museum? How do you get people engaged?”

Van Broekhoven’s and Thompson-Odlum’s are the largest of the questions facing the radicals. The controversies to which their changes have given rise revolve round the extent to which empires should be seen as a prolonged Holocaust. However it’s framed, what should be the attitude to apology, compensation, restitution? And will the audiences come along—especially if they are made to feel awkward about old-fashioned beliefs now redescribed as base prejudices and bigotries?

Dr Wiebke Ahrndt is director of the Übersee Museum in Bremen, and is herself a radical, if a measured one. She has introduced the new thinking on colonialism and its violence into her own museum, and is active in discussions about the issue in Germany and beyond. “I believe it’s an obligation on us to do this because the colonial past is largely forgotten. The debates and memories have been about the Third Reich and that has tended to push out other issues. And the visitors ask different questions—as about returning the articles. I believe they do think this is right to be discussed, and that the ethical issues are important.” She adds, however, that “I believe we have to look into the past and understand it, but we have more responsibility to the present. I would prefer to concentrate on that.”

The writer Tiffany Jenkins writes in her engaging 2016 book Keeping Their Marbles that “the past has become a surrogate area for struggle, with different groups competing to show their wounds of historical conflict… These social changes have helped to transform museums into key sites of cultural and political battles.” Jenkins traces some of the roots of contemporary museum radicalism to the loss of faith in the establishment of truth on the part of postmodernists: “In this context,” she writes, “thinkers began to be sympathetic towards ideas about the particularity of cultures.” In his book The Tyranny of Guilt, the French philosopher Pascal Bruckner detected something uglier beneath the increasingly familiar post-colonial complaint that “the Third Reich… has tended to push out other issues”:

Auschwitz has become a monstrous object of covetous lust. Whence the frenzied effort to gain admission to this very closed club and the desire to dislodge those already in it? Whence also the convergence of all suffering in Auschwitz, which becomes the desirable horror par excellence, the one whose heir everyone wants to be? … The victim madness has done so much damage that for some people the concentration camp uniform has become a garment of light. A trivialisation of genocide? It is exactly the reverse… What people want to strip from the victim in order to clothe themselves in it is the moral eminence, the tragic splendour it seems to enjoy. Suffering gives one rights, it is even the sole source of rights, that is what we have learned over the past century. In Christianity, it used to generate redemption; now it generates reparations.

Sir Mark Jones, who ran the V&A from 2001 to 2011, says that “the argument has, to a significant degree, been hijacked by those who believe that there is no such thing as legitimate trade—that all power is in the hands of white people, and they have taken from people of colour and colonial possessions and all that can be done is mass restitution. It’s a very Eurocentric point of view: that only the whites have agency, blacks can only be victims. I don’t subscribe to [director of the British Museum 1987–2002] Neil MacGregor’s position, that some museums are ‘world museums’ in ‘world cities,’ and thus have the right and duty to keep their items to be available to the world. I do recognize that there are some injustices of the past. But the past is the past. We should look forward. To try to impute the guilt of the past to those in the present is to open the door to horrible beliefs like the guilt of the Jews for the death of Christ.”

In mid-November, the present director of the V&A, the historian and former Labour MP Tristram Hunt, gave a Zoom seminar on his trade. He is, like his predecessor, a moderate, and he framed his working philosophy between two of Britain’s most storied writers—Rudyard Kipling and George Orwell. Orwell, he said, had both loved and hated Kipling, first for his sheer narrative skill, second for his embrace of a cruel empire which Orwell saw as a colonial policeman in Burma (now Myanmar) from 1922–27. Kipling had revealed both the romance and scope of the empire; Orwell saw the empire as “primarily a money-making machine held together by force.”

Like Kipling, the V&A reflects the sheer magnificence of the empire in many of its holdings (and its name). And like Orwell, Hunt said, it must now “work hard to expose the imperial past—in this we owe much to Orwell’s narrative.” But, he added, “for a museum like this, the notion of decolonisation makes little sense. We can be transparent and scholarly about the provenance of objects. Our role is to unleash more context and explanation of the past. Yet the museum can play a role as a distiller of history and an honest guide to the present.” The present and the future, he believes, is a prize to be won with honesty and clarity, not guilt.

This is a view widely shared by directors of Jones’s and Hunt’s generation and eminence. It was expressed again during another Zoom seminar in February by Sir Ian Blatchford, director of London’s Science Museum (no Benin bronzes there): “I am speaking for Middle England—people don’t want to tear down museums.” He instanced three figures, all active at the turn of the 17th and 18th centuries, who had bequeathed large sums for the construction of eminent institutions—Edward Colston, whose money helped establish All Souls College library; Sir Hans Sloane, whose museum provided much of the basis for the British Museum; and Sir Robert Geffrye, whose museum in London’s East End displays and celebrates domestic interiors. “All of these,” said Blatchford, “[had] strong connections with West Indian slavery, yet [were] hugely generous.”

This balanced case still survives but it is increasingly precarious: the past could be foul, the wealth it produced derived largely from slave labour, but the institutions it built can bear testimony to historical injustice and must therefore be preserved in those former imperial nations which now host them. The Benin bronzes, the bust of Nefertiti, and the Elgin Marbles may languish in cosseted captivity for a while yet. The larger question is this: will a new generation of scholars, curators, and directors—like the Pitt Rivers’s Van Broekhoven—succeed in changing the ethics and the practice? And what will that look like to the public?