Activism

The Threat to Academic Freedom: From Anecdotes to Data

The moral community is now self-reproducing. It is also self-radicalising.

Academia has become a closed system, a moral community defined by a set of sacred progressive values. The surge of no-platformings which took off in America in 2015 and hit Britain in 2018–19, or the fivefold jump in the rate of cancelling American academics which took place in 2019, present merely the tip of an iceberg of self-censorship and conformity. In this essay, I present extensive new survey data on the scale of the problem in the US, Canada, and Britain from my new report for the Center for the Study of Partisanship and Ideology entitled “Academic Freedom in Crisis: Punishment, Political Discrimination, and Self-Censorship.” This leads, at the end, into a discussion of policy solutions, where I argue that only government intervention can break the spiral of conformity gripping the contemporary university. The British government’s recent policy white paper on academic freedom, which adopted most of the recommendations of my previous co-authored report, “Academic Freedom in the UK,” is a blueprint that other jurisdictions are invited to follow. My current report represents an expansion of the UK report to encompass North America, where the situation is arguably even more pressing.

Progressive defenders of the status quo rightly point out that the total number of no-platformed academics represents little more than .01 percent of the total number of academics. They go on to claim that this proves that concern over progressive authoritarianism and low viewpoint diversity is nothing more than an opportunistic right-wing moral panic. My new report punctures this dishonest facade, exposing the pervasive structure of punishment, discrimination, and fear that underpins conformity to academia’s progressive sacred values and affects a majority of conservative academics.

Even if newsworthy incidents were the whole iceberg, there would still be cause for concern: would we so casually brush aside a few incidents of blatant anti-black or anti-Muslim exclusion? Yet something vastly more consequential lies beneath the surface. Universities are supposedly institutions dedicated to questioning received wisdom and pursuing truth. Veritas, Latin for “truth,” is Harvard’s motto, not “social justice.” Yet today, the search for truth is increasingly subordinate to a totalising creed that views tackling unequal outcomes between race, gender, and sexual identity groups as its sacred mission and conservatives—or even centrists—as moral reprobates.

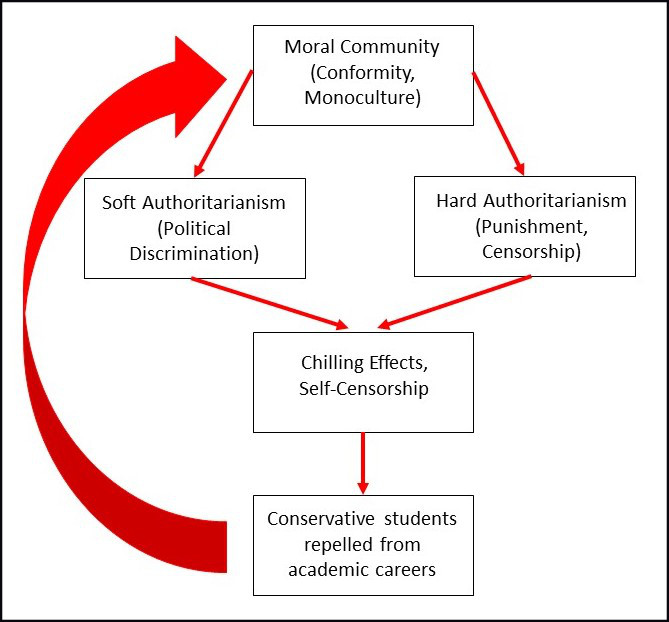

I could rely on painful and outrageous anecdotes of the Bret Weinstein, Charles Murray, or Kathleen Stock variety. However, as a social scientist, I think it’s also important to cite reliable and valid survey data which can lay the “just a few anecdotes” canard to rest. The report distinguishes between two forms of coercion: punishment and discrimination. The first represents what I term “hard authoritarianism” and consists of everything from a university firing an academic to a department head warning them through to colleagues bullying them. The second prong, “soft authoritarianism,” involves political discrimination, whether during hiring and promotion, or when refereeing a grant application or journal article.

As figure 1 below shows, the net result of punishment and discrimination is to create a climate of fear that leads political minorities like conservatives or gender-critical feminists to self-censor in research, teaching, and discussions with colleagues and students. This produces a hostile climate which repels those who hold minority beliefs from pursuing academic careers and pressures non-conformists to leave the system. The feedback arrow shows that this narrows viewpoint diversity, reducing opposition to the climate of conformity, shifting people’s sense of political reality to the cultural Left.

The moral community is now self-reproducing. It is also self-radicalising. In addition to dissuading conservatives, this climate of opinion attracts and empowers radical activists. These actors drive ideological crusades, calling out dissenters for blaspheming the sacred values of the ideological regime. Ideological homogeneity, as Cass Sunstein and John Ellis show, empowers extremists who exemplify shared values rather than producing an exchange of ideas that leads to a productive middle ground. Meanwhile, the paucity of conservatives weakens resistance to progressive intolerance, permitting radical innovators to establish illiberal policies such as “decolonizing the curriculum” or compelled diversity statements while instilling fear into potential dissenters. The moral community has become a closed system, reproducing itself, and becoming more radical over time. Heretics exist, but must remain under cover.

This doesn’t mean there is no limit to radical infiltration. The supply of radicals who can publish in established top journals is finite. Methodological rigour helps ensure that most academics remain moderate even if they nod to progressive enthusiasms. As in contemporary China, most feel that their freedom is relatively unaffected because they do not seek to challenge the regime. The moderate-left academic majority may well wonder what all the fuss is about. “How can you expect a man who’s warm to understand one who’s cold,” Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn is known to have remarked.

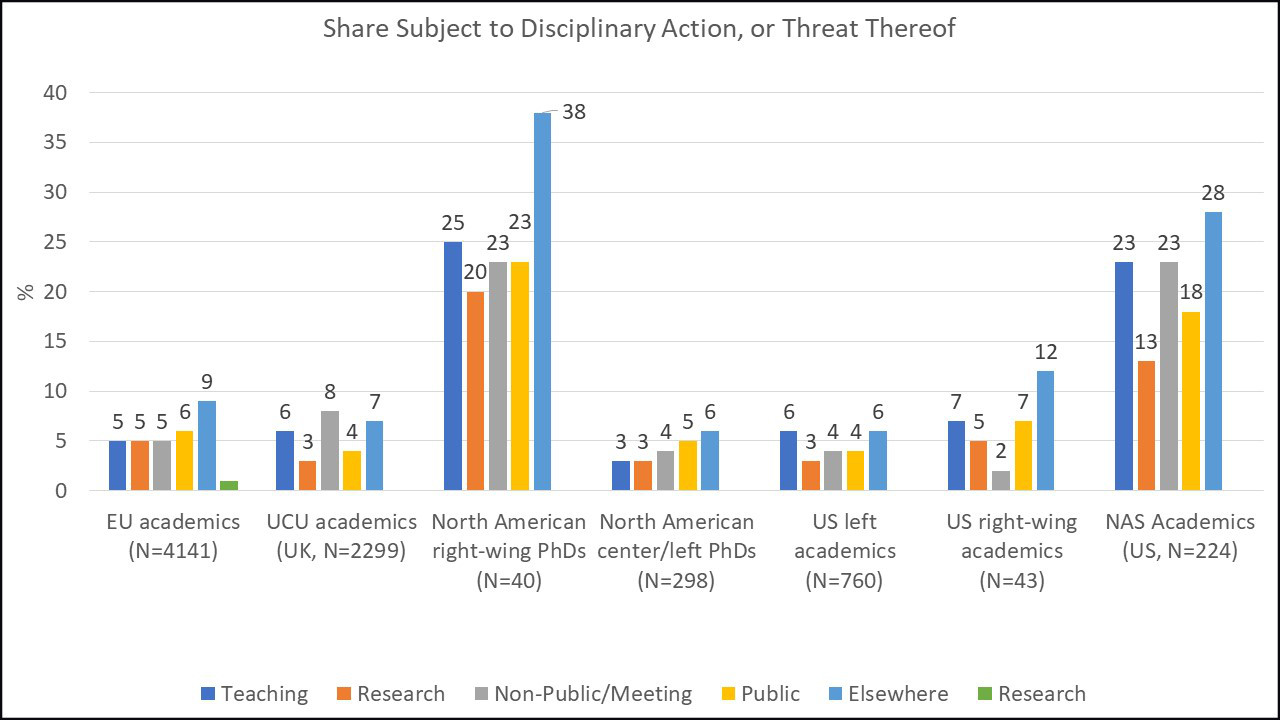

It’s now time to flesh out the model in figure 1. Let’s begin with punishment, the hard face of the system. Figure 2 shows results across two previous surveys (of European Union academics and UK-based Universities and College Union (UCU) member academics), as well as five sets of results from three surveys I conducted of American and Canadian academics and PhD students:

The first point to note is that thousands of academics have experienced disciplinary action for things they have written or said in research, teaching, or in public or private meetings. Across these measures, three to nine percent of the overwhelmingly left-leaning British UCU and EU academics report being disciplined or threatened for their views. Eleven percent of the UCU academics in Britain report being disciplined on at least one dimension. Fourteen percent of left-wing academics in my North American surveys report being disciplined on at least one dimension. While ideological conflict is a factor, factional and methodological disputes, as well as personality conflicts, can also produce hard authoritarianism.

Even so, what is noteworthy is that conservatives report an elevated level of punishment compared to other academics. One-in-three conservative academics and PhD students in the US say they have been charged or threatened with disciplinary action on at least one dimension. The situation is especially dire among conservative PhD students in North America, who report very high levels of administrative threat—from 20 to 38 percent on each of five dimensions, with 83 percent reporting threat on at least one. To surmount my small sample of 43 conservative academics and 40 conservative graduate students, I polled members of the National Association of Scholars (NAS), an organisation whose membership in my sample is 60 percent conservative. While there is self-selection of academics concerned with academic freedom into the NAS, the fact that 46 percent say they have been charged or threatened on at least one dimension provides, alongside my other samples, further evidence of higher punishment levels for conservatives.

I also collected testimonials from respondents, asking people to describe their experiences. This unearthed a number of instances of everyday repression, as with one conservative American geographer who reported that “The university is right now considering disciplinary proceedings because of innocuous items I posted on my private blog. I think I’ll be alright, but conservative academics are somewhat persecuted for their views.” A conservative professor in Education added that “every year I am called into my boss’s office because of some controversy surrounding course curricula.” While I don’t have comparable data on gender-critical scholars, it is noteworthy that around 10 percent of comments from left-wing academics mentioned problems arising from their stance on the transgender issue, the most commonly reported problem. As one left-wing Canadian anthropologist related: “I have been dismissed as undergraduate programs chair in my department because I am a gender critical feminist. Students currently have a petition underway supporting this dismissal.”

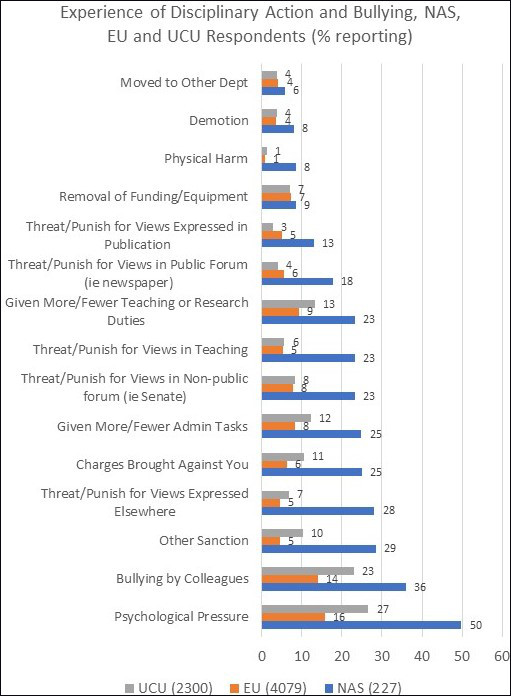

Figure 3 offers a more detailed look at a range of disciplinary threats, drawing from both the UCU surveys and my NAS replication of the same questions. This reveals threat levels two to four times higher among NAS staff compared to the left-leaning EU and UCU samples. It’s one thing to brush aside no-platformings and dismissal campaigns as rare compared to a denominator of 100,000 academics in Britain or over half a million in America. It is considerably harder to downplay the hard authoritarianism being reported by around a third of American conservative faculty and graduate students and a 10th of all British academics. Recognising the dire state of protection for academic freedom in Britain, the authors of the UCU study recommended more robust legal protections for academic freedom against the authoritarian pressure coming from their universities, something echoed in my co-authored Policy Exchange reports on Academic Freedom in the UK in 2019 and 2020. Thankfully, the UK government has listened, and has adopted most of our recommendations in its February 2021 white paper.

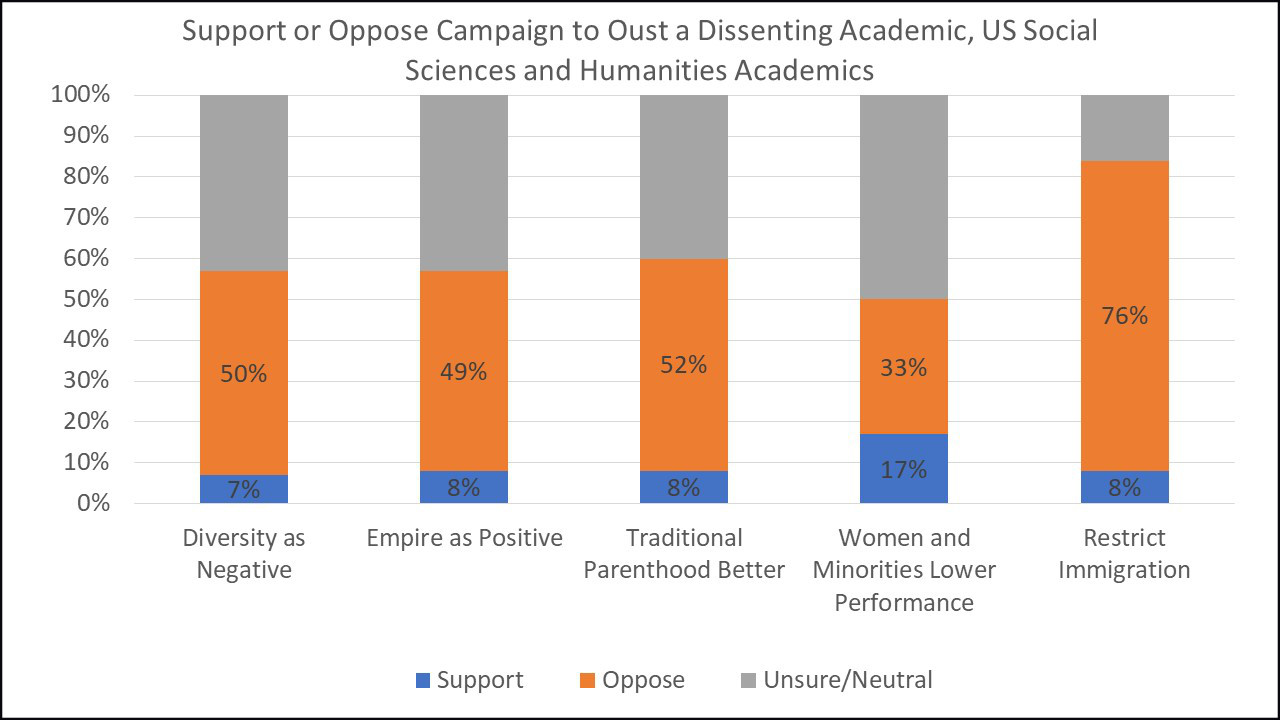

We’ve considered experiences of victimisation, but what about academics’ willingness to discipline speech? University administrations are an important player in the disciplinary process, but many of the complaints about academic punishment in figure 3 pertain to action from colleagues, often in their capacity as department heads or in other administrative roles in the university. In order to measure the level of academic support for disciplining speech which challenges progressive sacred values, I devised five hypothetical scenarios. These are loosely modelled on actual cases, and, regardless of whether they disapprove of the conclusions, I felt it was important to gauge whether people were willing to permit these academics the freedom to make their case. The five scenarios were as follows:

- If a staff member in your institution did research showing that greater ethnic diversity leads to increased societal tension and poorer social outcomes, would you support or oppose efforts by students/the administration to let the staff member know that they should find work elsewhere? [Support, oppose, neither support nor oppose, don’t know]

- If a staff member in your institution did research showing that the British Empire did more good than harm, would you support or oppose efforts by students/the administration to let the staff member know that they should find work elsewhere? [Support, oppose, neither support nor oppose, don’t know]

- If a staff member in your institution did research showing that children do better when brought up by two biological parents than by single or adoptive parents, would you support or oppose efforts by students/the administration to let the staff member know that they should find work elsewhere? [Support, oppose, neither support nor oppose, don’t know]

- Please imagine a member of your organisation has done work showing that having a higher share of women and ethnic minorities in organisations correlates with reduced organisational performance. Several thousand professionals, some from your organisation, have signed an open letter calling for the staff member to be fired in order to protect disadvantaged groups from a hostile learning environment. A small group have started a counter-petition defending the staff member on grounds of academic freedom. Would you: [a) Sign the open letter, which called for the staff member to be fired, b) Support the views expressed in the open letter, but choose not to sign it, c) Not support nor sign either letter, d) Support the counter-petition, but choose not to sign it, e) Sign the counter-petition, f) Don’t know.]

- If someone in your department was known to favour restrictions on immigration, would you support efforts by students/the administration to let the person know that they should find work elsewhere? [Support, oppose, neither support nor oppose, don’t know]

Figure 4 shows how American academics responded to the hypotheticals. The good news is that support for dismissing dissident professors is low. Generally around 10 percent in the US, Britain, and Canada, reaching a maximum of 13–18 percent on the organisational performance question. Most academics do not support cancel culture.

However, the picture is not all rosy when it comes to academic freedom. Notice that the share who oppose cancellation is only resounding—76 percent (83 percent in Britain)—in the case of firing an academic who favours lower immigration levels. Across the rest of the items in figure 4, 40–51 percent were unsure or neutral: not favouring dismissal, but not opposing it either. This was especially true for the hypothetical finding that women and minorities lower organisational performance, where 51 percent of American and 60 percent of British academics marked the neutral or “don’t know” boxes.

These results tell us that few academics support cancel culture, but a large minority or even a small majority are complicit in its operation. This is, in my view, because many are cross-pressured between their support for academic freedom and their adherence to the left-modernist goal of equalising material and psychic outcomes for historically disadvantaged race, gender, and sexual identity groups. It is also important to recognise that among the roughly half of academics who oppose cancel campaigns, a slight majority said they would publicly oppose cancellation. Only for PhD students did a majority of opponents say they would keep their views private. While the idea of a “silent majority,” drawn from Timur Kuran’s idea of preference falsification, cannot be ruled out, these answers indicate that the problem is as much one of winning hearts and minds as of unleashing the courage of a faculty overwhelmingly committed to academic freedom.

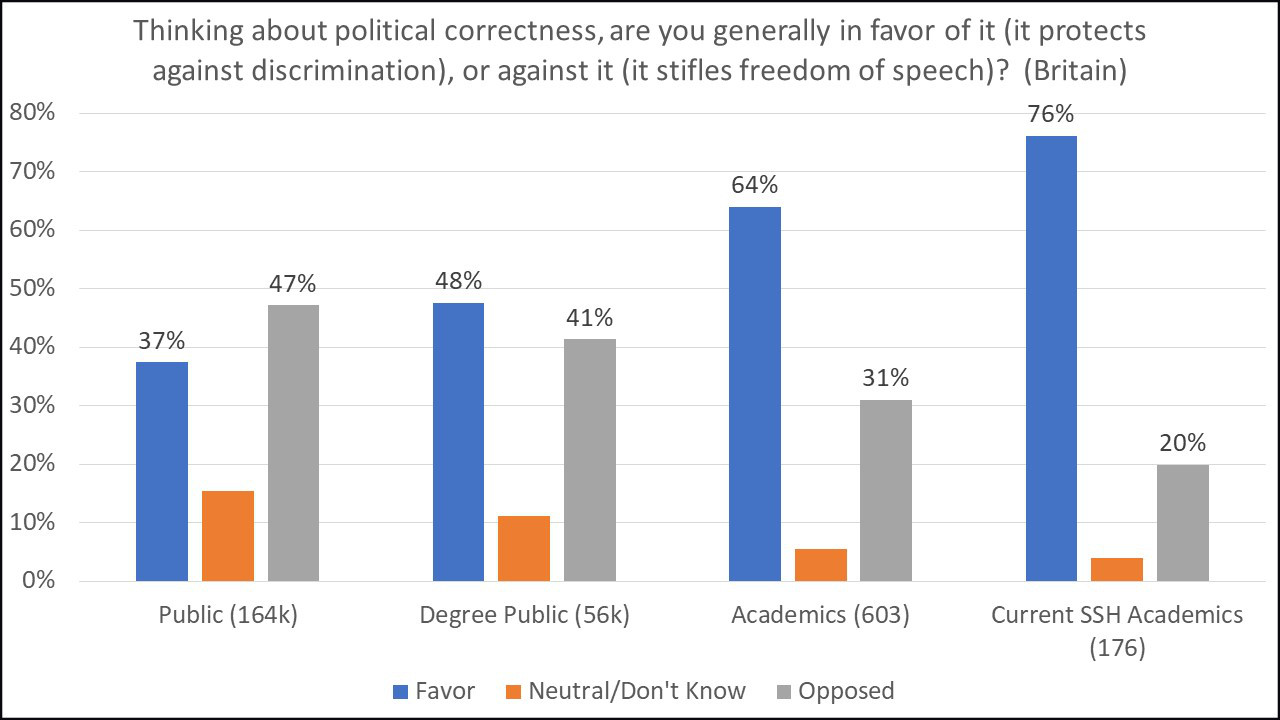

To illustrate how far the battle of ideas is from being won, we can examine a question fielded by YouGov in Britain which asks whether people support political correctness because it protects minorities from discrimination, or whether they oppose it as a threat to free speech. Figure 5 shows that, when phrased this way, the 164,000 members of the British public who were polled on YouGov’s massive Profiles panel oppose political correctness more than they support it by a 47–37 margin while the degree-holding public backs it by a modest 48–41. However, the 603 British active and retired academics in my sample who could be matched to the YouGov data on this question backed political correctness by a 64–31 margin, rising to 76–20 among the 176 currently active social sciences and humanities (SSH) academics. This demonstrates considerable academic preference for minority protection over free speech, at the abstract level, when the two values collide.

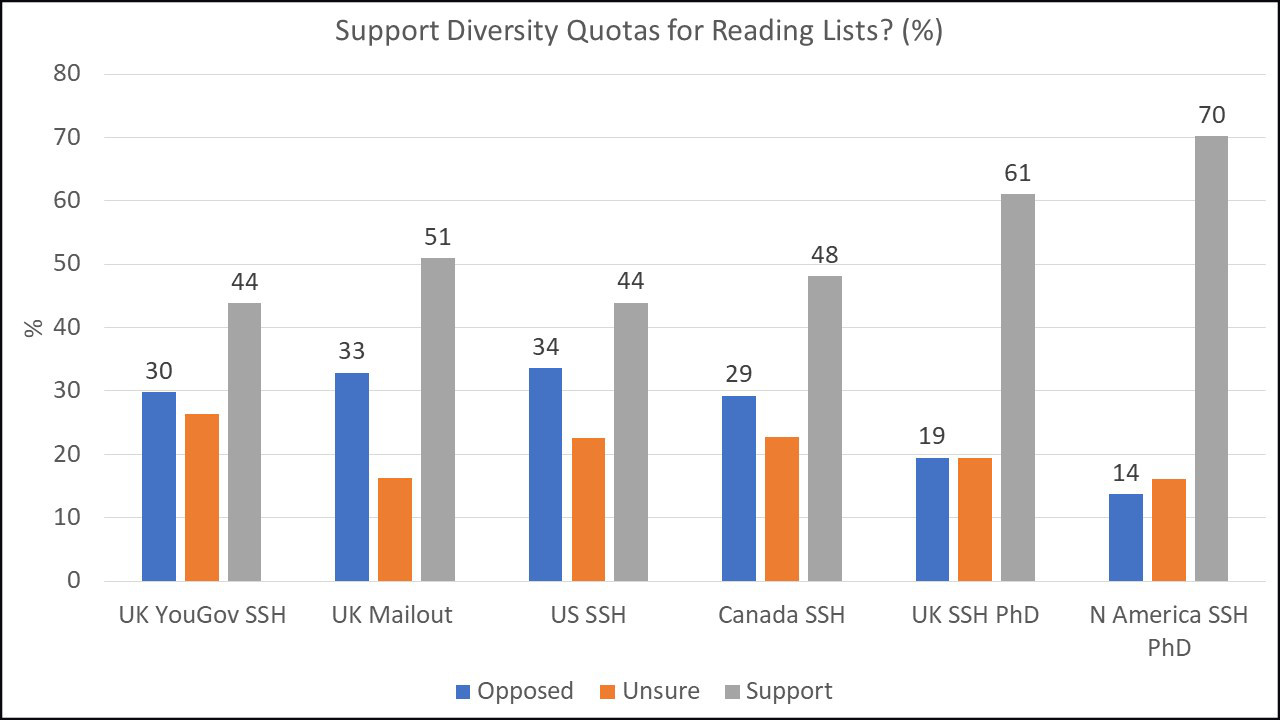

Another question that reveals academics’ pronounced predilection for progressive aims concerns “decolonizing” the curriculum. To wit, “Please imagine there was a new initiative in the Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences at your institution, stipulating that on each reading list, at least 30 percent of readings must come from women and 20 percent from ethnic minority authors.” Responses included supporting this publicly, supporting it privately, neither, opposing it privately, and opposing it publicly.

Figure 6 shows that among academics in SSH disciplines—the majority of the academic sample—about half (44–51 percent), and a clear majority of PhD students (61–70 percent), support mandatory race and gender quotas on reading lists. Against this, just a third of academics, and 15–19 percent of doctoral students, opposed the measures. No wonder the idea of decolonizing the curriculum has spread widely across university departments.

A related question asked respondents whether they prioritised academic freedom or social justice. The term “academic freedom” may have primed academic respondents to recalibrate because this time there was a clear majority for the liberal position: 58 for compared to 26 against in the US and 53–34 in Canada (I have no data for Britain). Among doctoral students, by contrast, social justice was viewed as more important than academic freedom in North America by a 40–34 margin, and nearly as important as academic freedom, at 33–37, in Britain.

These views appear to be relatively solid: asking respondents to read a paragraph outlining the virtues of free speech had no effect on PhD or academic views on the priority of free speech in any country. Only in the case of undergraduate students did the free speech paragraph have a significant effect in shifting opinion, by around 15 points in favour of prioritising free speech over “emotional safety.” On the flip-side, a paragraph promoting emotional safety pushed British undergraduates a similar distance against the free speech option.

British academics were the only scholarly group that could be manipulated, and only in a progressive direction. I asked them to read a diversity statement modelled on that of the University of California. In my YouGov survey, 39 percent of British academics who read the diversity statement went on to reply that it was more important for reading lists to reflect the racial and gender makeup of students than to be based on “foundational texts,” whereas just 25 percent of those who did not read the diversity statement prioritised race and gender representation over foundational texts. This finding replicated on my British emailed online survey.

Younger and far-Left academics, as well as Brexit supporters, were unaffected by reading the pro-diversity paragraph, suggesting that their views are now fixed. American and Canadian academics were similarly unmoved by the diversity statement, indicating that opinions have largely crystallised among North American scholars, and, in Britain, among younger academics and PhD students. That is, groups already acquainted with this debate are less biddable. Future attempts to change attitudes must therefore focus primarily on undergraduate students.

Academic support for punishment

Support for quotas carries severe implications for academic freedom. Are the academics who favour decolonizing the curriculum ready to quash the liberty of those who want the right to choose their own readings? To find out, I asked American and Canadian academic supporters of quotas what should happen to colleagues who refuse to amend their lists to comply with a quota policy. Table 1 shows that on the one hand, just 12 percent support firing dissidents or cancelling their courses. This is good news, but also reveals that many academics may not be aware of the implications that their progressive enthusiasms have for academic freedom. On the other hand, 63 percent recommended at least one course of action contrary to the spirit of free inquiry, be this compelled implicit bias training, social pressure or less favourable teaching, administration or research funding. Here we see the authoritarian wolf that lurks in the sheep’s clothing of progressivism. This also helps explain the significant rates of punishment experienced by conservatives in figures 2 and 3.

Table 1. Preferred Punishment for Reading List Race/Gender Quota Non-Compliance among Pro-Quota North American Academics

Answer | Percent |

| Don’t know | 15 |

| No action of any kind | 12 |

| No formal or informal pressure, but must take extra implicit bias awareness training | 28 |

| No formal disincentives, just social pressure | 27 |

| Give them less favorable teaching and administrative roles, or access to research funding | 7 |

| Cancel the course, make them teach a course that meets the quotas | 9 |

| Terminate employment due to breach of contract | 3 |

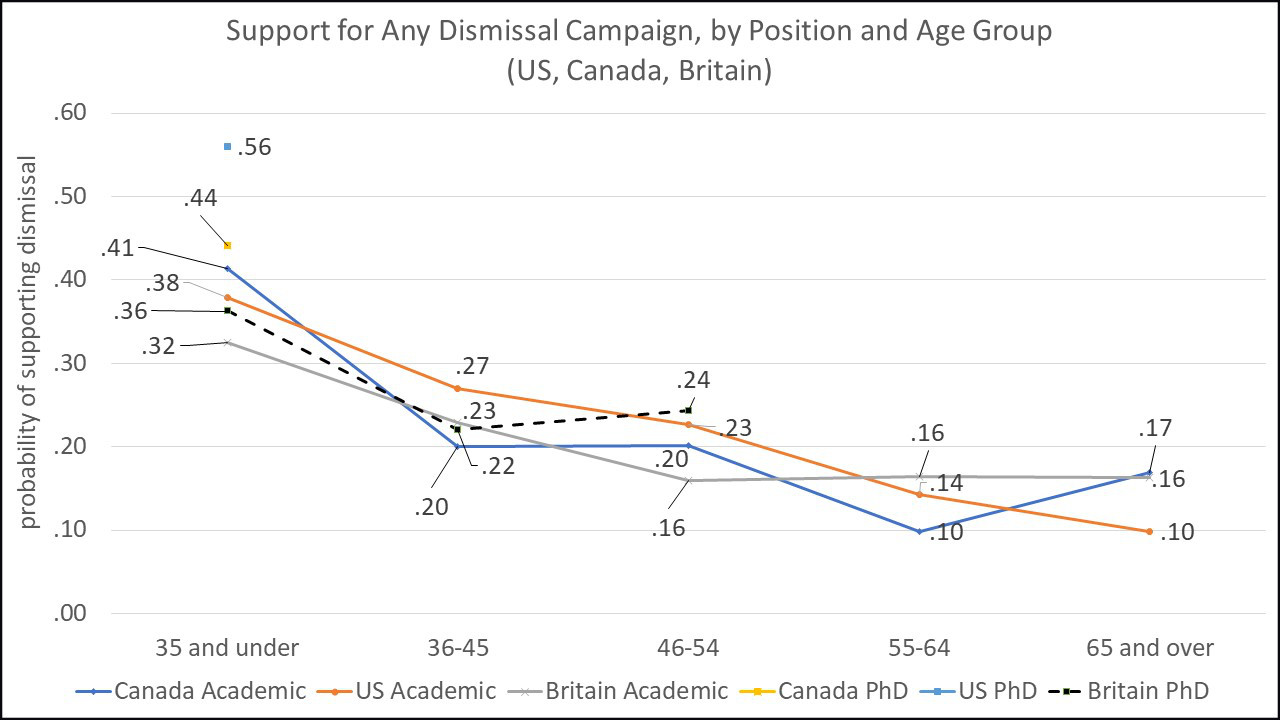

The anti-freedom tilt of doctoral students is a red flag which raises the disconcerting reality that younger scholars are more intolerant than today’s academics even though they are ideologically similar to older academics. As figure 7 shows, academics under the age of 35 are twice as likely to support at least one of the dismissal campaigns in figure 4 as those over 50. American PhD students are around three times as likely to back at least one campaign as academics over 50: they have a .56 probability of supporting at least one of the cancellation scenarios in figure 4. Moreover, while faculty in North America over 50 prioritise academic freedom over social justice by a three-to-one ratio, the two are evenly matched among their counterparts aged 30 and under. In regression models, age is as or more important than being far-Left when it comes to backing a dismissal campaign, or prioritising social justice over free speech. If these changes are generational, as longitudinal studies of student data from the 1990s to the 2010s suggest, then the climate for academic freedom is going to become more, rather than less, difficult in the years and decades to come.

Political discrimination

No-platforming and dismissal campaigns have become frequent only recently. The NAS reports 65 new incidents in 2020, a fivefold increase over the preceding year, while the FIRE disinvitations database shows a big rise in left-motivated no-platformings beginning in 2015. However, this shouldn’t blind us to the more severe longstanding problems stemming from political discrimination and lower-level disciplinary action.

Here it is worth remembering that American campus speech codes, nearly 90 percent of which are unconstitutional, began to be enacted in the late 1980s, when the phrase “political correctness” first emerged. We shouldn’t make the mistake of imagining that the current upsurge of intolerance is a new fad that will pass, like McCarthyism, from the scene. Rather, it is a deeply embedded feature of today’s dominant ideology, left-modernism, which has become progressively institutionalised since the late 1960s. Academic illiberalism is arguably in its sixth decade, and has been a feature of elite universities for four decades.

While hard authoritarianism in the form of punishment is one arm of the system, political discrimination arguably poses a more pervasive threat. Using a concealed list technique, I found that 40 percent of American academics wouldn’t hire a known Trump supporter, rising to 45 percent among Canadian academics. One-in-three British academics wouldn’t hire a known Brexit supporter. Trump was elected president with nearly half the popular vote in 2016. Brexit passed 52–48 on a 72 percent turnout. The fact these mainstream views are deemed grounds for discrimination is disconcerting.

In line with previous studies, I also found substantial discrimination against conservative grant applications, paper submissions, and promotion applications. Adopting a multiplier derived from the Brexit and Trump experiment, this means that between a fifth and a half of academics would discriminate against the Right in grants, papers, or promotion bids. On a four-person panel, this means that the likelihood of a conservative encountering at least one biased assessor is pushing toward certainty.

Discrimination can be social as well as professional. Collegiality is a big part of academic life, and an important aspect of workplace satisfaction. But academics were cool about the idea of sitting down to lunch with a Brexit or Trump supporter. Barely half of British academics would be comfortable having lunch with a Brexit voter, and just 41 percent of American academics said they would be comfortable dining with a Trump supporter. Gender-critical academics faced even harsher headwinds: just 28 percent of American and Canadian academics, and barely a third of British academics, would have lunch with someone opposed to the idea of transwomen accessing a women’s shelter. Alongside evidence that gender-critical feminists have been no-platformed more than any other group, this suggests that they face the highest level of discrimination of any political minority in academia.

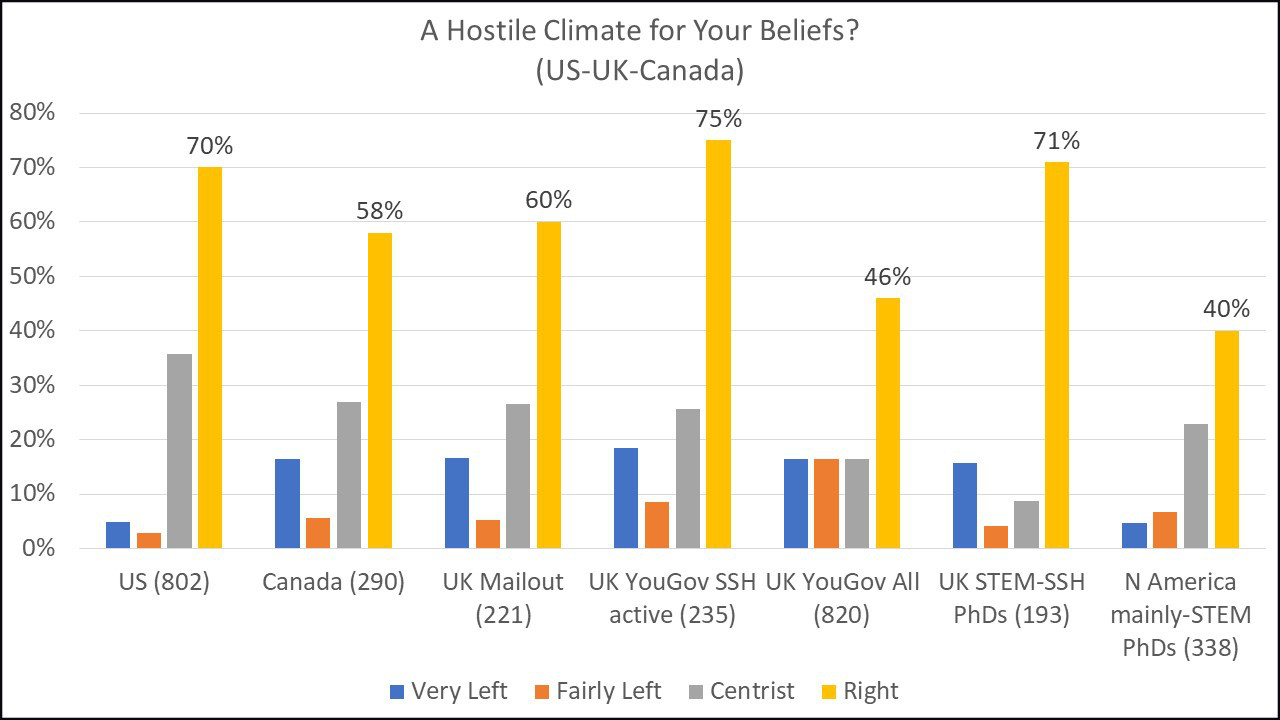

Punishment and discrimination, as I sketched in figure 1, creates a hostile climate for political minorities, and chills their academic freedom. Figure 8 shows that right-leaning academics consistently report significantly higher hostility than left-leaning academics—a finding that replicates results from a series of previous studies. If we exclude retired academics, who make up 40 percent of my British YouGov sample, nearly all my surveys show that a majority of conservatives say their departments are hostile rather than supportive environments for their views. Limiting the analysis to active SSH academics, fully 75 percent of British and American conservatives say they work in a hostile department for their beliefs. In SSH fields, centrists also report relatively high hostility, with 40 percent of American SSH academics saying they work in a hostile environment compared to just four percent of their leftist colleagues. It is also worth noting that in Canada and Britain, far-leftists generally report more hostility than moderate leftists. Indeed, British academics were similarly uncomfortable having lunch with supporters of the far-leftist Jeremy Corbyn as with Brexit supporters.

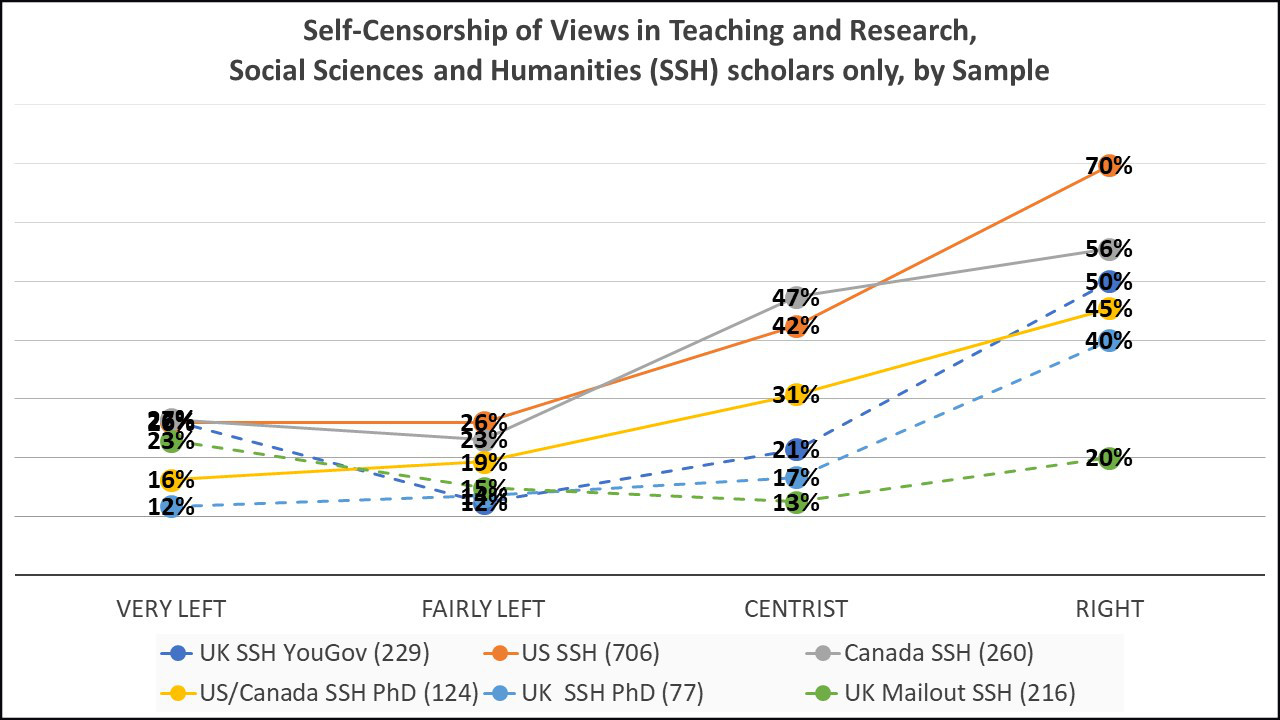

Hostile environments translate into chilling effects which silence speech and inquiry. Figure 9 focuses on SSH disciplines, highlighting that the minority of academics who are politically on the right report much higher levels of self-censorship than those on the left. In the US, 70 percent of conservative SSH academics self-censor in research, teaching, and academic discussions. 56 percent of Canadian, and 50 percent of British, academics on the Right, also do so. In North America, nearly half (42–47 percent) of centrist academics report that they self-censor, as do 21 percent in Britain. This indicates that progressive conformity affects the centre as well as the Right, but is more oppressive in North America.

Is academia more biased than other professions?

These results may appear to indicate that academics, or leftists, are uniquely biased. However, there is plenty of research to indicate that political discrimination is a widespread feature of our society. Using a survey of college-educated workers in Britain, and comparing it with my surveys of academics, I found that the willingness of conservatives to discriminate against leftists, and vice-versa, was similar among Left and Right, both inside and outside academia. Nevertheless, that survey also found that employees in universities were far more likely than degree-holders in other sectors to say that Brexit supporters would not be comfortable expressing their views to colleagues. What explains the higher chilling effect in universities?

The problem lies partly with the fact that people’s views are transparent in their work in SSH fields, and partly in the extreme political skew of academia. For instance, in my UK survey, supporters of right-wing parties among SSH academics were outnumbered 7:1 by supporters of left or liberal parties, and in my North American surveys by a whopping 14:1. The latter is quite close to the 11.5:1 Democrat-to-Republican voter registration ratio unearthed by Mitchell Langbert and colleagues in an exhaustive sample of current faculty in the top 60 American universities for History, Journalism/Communications, Law, Economics, and Psychology. This is especially so when Economics (at 4.5:1) is excluded (I excluded Economics from my SSH category).

When the Left outnumbers the Right 14:1, it doesn’t matter that right-wing academics are discriminating at equal rates to their leftist counterparts. The aggregate effect of two-way discrimination hits the Right far more, and my academic surveys show that discrimination in favour of left-leaning applications and papers often cancels out discrimination against them. This leads to self-censorship on the Right but not on the Left. No wonder studies of legal scholarship find that the work of registered Republican academics cannot be identified by coders, whereas that of Democrats often can be because they openly espouse their values in their work.

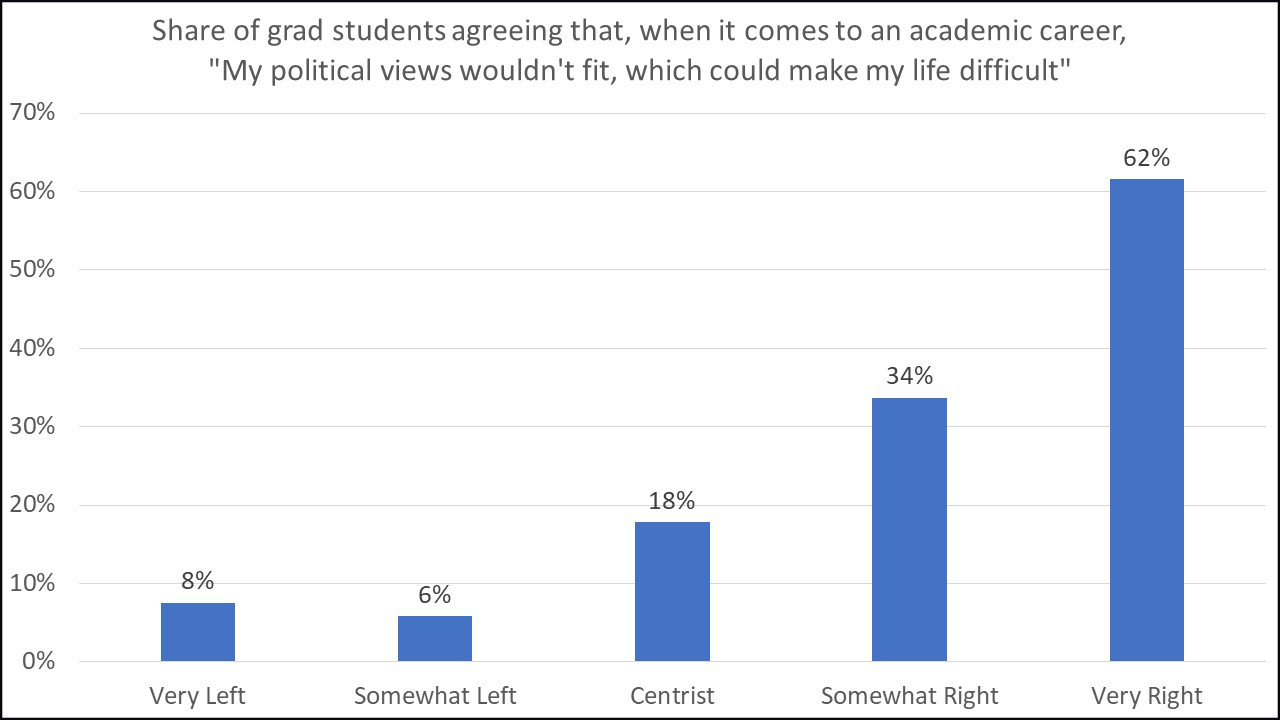

The result of punishment and discrimination is hostility and self-censorship, which deters political minorities such as conservatives from pursuing an academic career. Figure 10 shows that, when asked about considerations that might affect their decision to pursue an academic career, conservative graduate students are much more likely than others to express concern that their political views will make their life difficult in academia. This predicts lower interest in pursuing an academic career among right-leaning SSH master’s students. I also find a significantly higher share of right-leaners among British academics who retire early, suggesting that selection effects work to both limit the entry of, and hasten the exit of, conservatives.

It’s not clear whether chilling effects, stereotypes about academia, the limited breadth of interests represented by academic staff or active discrimination best explains why SSH academia is more politically skewed than other professions and has shifted from a 2:1 or 3:1 Left-to-Right ratio in the 1960s to somewhere between 9:1 and 14:1 today. The relatively progressive politics of people with advanced degrees accounts for only part of the political homogeneity of SSH academia.

Policy options

Academic freedom and viewpoint diversity seem to be caught in a downward spiral as conformity to the left-modernist values of the moral community on campus stifles the university’s truth-seeking mission. How can we break this spiral and free the university? Only external intervention from government, in my view, can reverse the damage.

In a separate article published soon after my report’s release, which may be read as a policy chapter to the report, I distinguish two approaches to reform; libertarian and interventionist. Libertarian actors such as the Heterodox Academy, FIRE, the Academic Freedom Alliance, and the Free Speech Union believe that legal advice, free speech rankings, lawsuits, and public information campaigns can revive the free speech culture and lead liberal actors to vote with their feet for openness, incentivising universities to change.

While such efforts are vital, and these organisations are correct that academic freedom will only truly be safe when there is a consensus in favour of the free speech culture, my report suggests that threats to academic freedom on campus are likely to increase as younger cohorts enter the ranks of academia. This means more pressure from activists on universities to curb academic freedom. A reactive approach in which dissenters must engage in costly and time-consuming legal battles effectively concedes defeat. “The punishment is the process” and a defensive stance is a “recipe for failure,” notes a University of Texas professor. Accusers are free to try their hand again and again, no matter how often the accused escapes punishment. The result is a chill on prospective dissent and self-censorship, fulfilling the aim of the left-modernist speech police.

The only means of resisting this is to open the university to scrutiny from government, in line with the law, which is accountable to voters, the media, and the courts in a way backroom university meetings and tribunals are not. Society is not merely composed of the government and citizens, with government the only threat to liberty. There is also an intermediate layer of institutions, such as universities, corporations, or organised religion, which can threaten liberty. In these cases, government intervention protects the freedom of citizens, even if it infringes on institutional autonomy for a time. The federal government’s forced de-segregation of southern universities in the early 1960s to protect the liberty of black citizens is good example of this. Libertarian purists who reflexively react against “government” wind up serving as the useful idiots of left-modernist authoritarianism.

Moreover, the libertarian analysis fails to appreciate the structural, deep-rooted sources of self-censorship in universities. The problem didn’t start in 2015, but in the late 1960s, as Nathan Glazer remarked in 1969:

The Free Speech Movement, which stands at the beginning of the student rebellion in this country, seems now almost to mock its subsequent course. In recent years, the issue has been how to defend the speech… The right of unpopular political figures to speak without disruption on campus; the right of professors to give courses and lectures without disruption that makes it impossible for others to listen or to engage in open discussion; the right of professors to engage in research they have freely chosen… all these have been attacked by the young apostles of freedom and their heirs.

In the late 1980s, the children of the ’60s emerged as a force in universities. These were the years when political correctness, multiculturalism, and Afrocentrism reared their heads and universities enacted their first speech codes. These are almost all unconstitutional, yet remain on the books. As universities became increasingly left-dominated in the late 1980s, political discrimination became more pronounced, further narrowing the ideological range among the faculty and setting a self-fulfilling spiral in motion. As radicals came to occupy positions of power in the university, punishment joined with discrimination to drive conformity. Taboos around race, gender, and sexuality acted as force multipliers, allowing the radical minority to intimidate the majority of faculty. Are we really prepared to endure another 40 years of political discrimination and injustice against political minorities, and more decades of political monoculturalism, in the hope that somehow, against the grain, campus culture will change?

In my co-authored report on Academic Freedom in the UK, from which a portion of the UK data for my CSPI report was drawn, we recommended a number of legislative and policy changes to the UK government. Importantly, most of our recommendations were adopted in the government’s new Academic Freedom white paper, which is likely to become law later this year. Foremost among these is the creation of the new position of Academic Freedom Champion on the Office for Students (OfS), the sector regulator. This individual will be tasked with proactively auditing universities for compliance with their free speech duty to not only defend, but promote, academic freedom. In addition, this office will act as an ombudsman to hear cases from individuals whose rights have been abridged by their universities. The new bill gives the regulator teeth to fine universities, which is vital. Only if the cost is high will administrators be able to face down activists and tell them that they cannot restrict the freedom of dissenting academics, no matter how much they wish to do so.

These measures should address hard authoritarianism, but we know that political discrimination is the bigger issue fuelling the chilling effects that affect most conservatives, gender-critical feminists, and a near-majority of centrists. Accordingly, our recommendations also include an explicit mention of political discrimination as grounds for bringing a complaint against a university. I recommend that university officers, when speaking in an official administrative capacity, be governed by a duty to remain politically neutral on any issue not directly concerned with the university’s narrow sectoral self-interest. Finally, I’ve argued for a requirement that universities show equivalent action between policies to promote traditional forms of diversity and equality, and moves to promote viewpoint diversity and equality. Institutions would be free to dial down all forms of equity and diversity, but should not be permitted to privilege identity-based diversity over political diversity.

In the US and Canada, federal and provincial or state laws have either focused on abstract free speech policies which have little practical impact on everyday practices in universities, as in Ontario and Alberta, or are incoherent in their defence of academic freedom, as in many Republican-controlled states. Attention has too often focused exclusively on a few no-platforming incidents. Consistency should be the watchword. You cannot enforce a speech code defining anti-Semitism more tightly than the law, as has occurred under the Trump administration in America or the Ford premiership in Ontario, and simultaneously hope to be taken seriously when arguing against similar codes for transphobia or racism. Mooting affirmative action to promote the hiring of conservatives, as South Dakota seems to have done, is similarly illiberal unless tied to an argument over equivalent action with other forms of equality and diversity. Similarly, attacks on tenure, as in Iowa, or the banning of non-compulsory courses on Critical Race Theory (CRT), as in New Hampshire, Georgia, and Oklahoma, run contrary to principles of academic freedom. CRT should be prohibited only when made compulsory and taught in an uncritical manner. State legislative action has done some good by banning free speech zones, but future activity needs to be consistent, principled, and proactive to target the problem. In this regard, the UK model is one that other jurisdictions should follow.

Few people think that the desegregation of southern universities, or the British government’s takeover of Islamist-controlled public schools in Britain, was a bad idea. With patient and principled regulation, public universities can be freed from their current spiral, allowing them to return to their truth-seeking mission. Private universities that accept public money can also be incentivised to be liberal. This will safeguard academic freedom for political minorities, improving the production of knowledge and the student experience while enabling the conversations that can heal our growing political divisions.