Activism

Sexual Assault and the Taboo of Sound Advice

Yes, your car might be stolen even if you lock it and take the keys, but does that mean that no one should remind us to lock our cars and take our keys?

One recent Friday, campus police at University of Nevada Las Vegas (UNLV), sent out a school-wide welcome email offering safety tips to students, some of whom are incoming freshman and the rest of whom would be on campus for the first time in a while. “With the first week of classes now underway,” the email began, “I’d like to take this time to remind you that University Police Services is focused on preserving an environment where you can study, live, and work safely.”

The opening tips were in the realm of those familiar body-language prescriptives that some find hokey but that self-defense experts swear by: “Look confident, keep your head up and walk with a confident stride.” The email emphasized that merely making eye contact could establish one’s status as an alpha and thereby “deter a potential attack.” The advice continued: “Be aware and alert to your surroundings. Don’t talk on your cellphone or listen to music when you are in an unfamiliar area” and “If you jog alone, stay in public areas that are well lit and populated” and “It is a good idea to prepare yourself… so you don’t freeze with fear if something ever was to happen.” Commonsensical advice, right?

Not among those sworn with ecclesiastical fervor to support victims of rape, domestic violence, and similar crimes, whose principal function seems to be to sniff out rhetoric that makes victims feel discomfort having been victimized. Those advocates, hailing from several UNLV entities, apparently got on the horn and raised holy hell with the campus cops. Duly chastened, by first-thing Monday, they had sent out a sheepish mea culpa. Campus PD wrote now to “sincerely apologize” for the “inadvertently sent” email’s “effects on our students, faculty, and staff.”

Not content to let it go at that, the victims’ advocates soon weighed in with a more pointed campus-wide denunciation of the original memo:

For folks who’ve been impacted directly or indirectly by violence, it may have been frustrating or even painful to open up your email and read the same harmful and victim-blaming language. The CARE Center and SDSJ recognize that framing violence prevention around “being confident,” “being alert and aware of your surroundings” and other tips that place responsibility on the individual to avoid being attacked erase the lived experiences of so many of us. We want to reiterate that no matter the circumstances, victim-survivors are not responsible for crimes or violence committed against them. Our hope and commitment for the future is that you never are made to feel like violence was your fault, and instead that you feel cared for and supported by the institution you’ve entrusted with your safety and education.

This kind of overwrought response to initiatives designed to spur people to be more proactive about personal safety has become not only culturally entrenched but impolitic to rebut. The fact that Campus PD sent out its initial email at all was something of a shock to me, albeit a happy one given that the pointers offered a useful “refresher course” to students living, working, and partying in a college setting for the first time in a year thanks to COVID-19. Nonetheless, such once-commonplace advisories basically became verboten a few years ago at the height of the putative campus “rape crisis” (when you also might have thought sound advice would be useful).

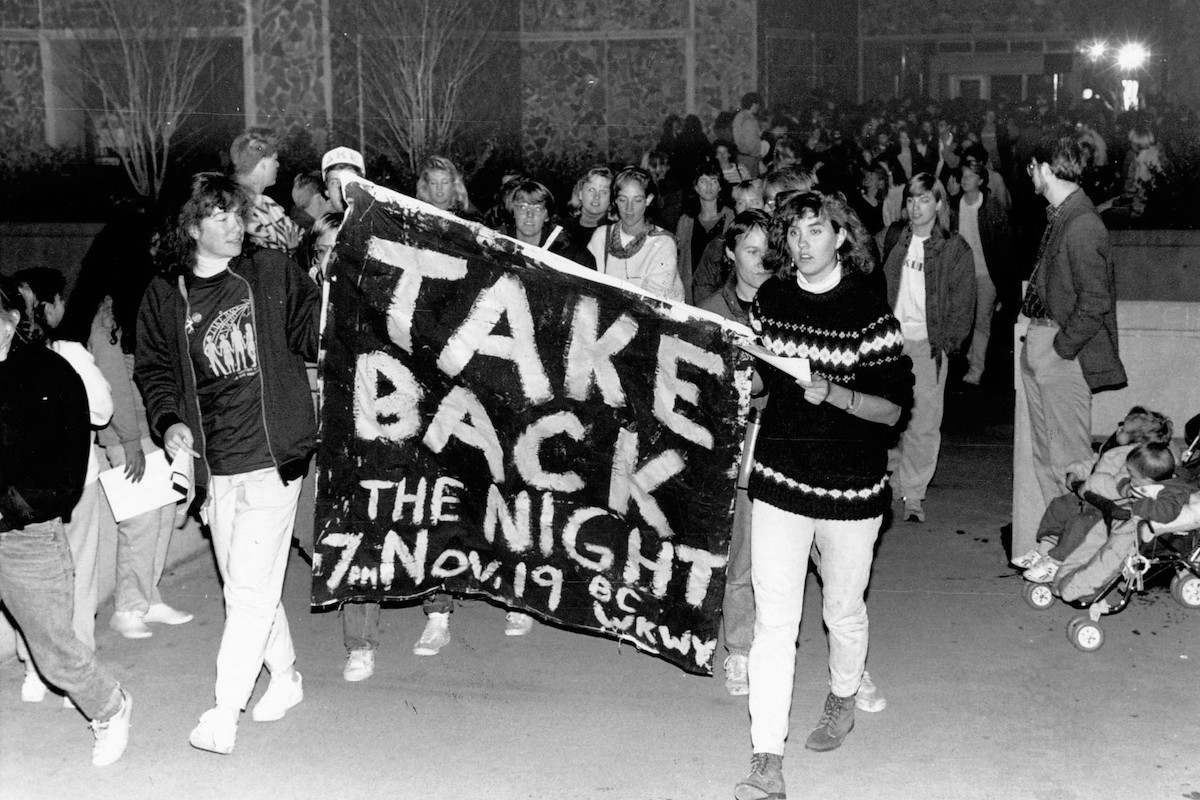

Activists claimed that such language harked painfully back to a time when women who’d been sexually assaulted were then browbeaten with questions like “What were you wearing?” and “Have you been drinking?”; they succeeded in establishing an ethos which insisted that a victim’s behavior is simply not a fit topic for discussion in the aftermath of an assault. The blame—the only blame—must reside with the perpetrator, on the fallacious assumption that fault is a finite, zero-sum resource, and that acknowledging a victim’s responsibility for her own safety therefore somehow absolves her attacker of full responsibility for his violence.

Today, the climate is such that even a sober-minded mainstay publication like Forensic Research and Criminology Journal (FRCJ) gingerly frames as a “controversial theory” the notion that certain imprudent behaviors may result in undesirable outcomes—even while adding with an ostensible note of surprise that research shows that this so-called “victim precipitation” happens “with some frequency.” Indeed, in one small study, 18 percent of homicide victims were deemed at least somewhat complicit in their own murders. Once upon a time, there were similar (tentative) studies of rape, though if there’s a third rail of modern criminology, that would be it.

The Rape, Abuse, & Incest National (RAIN) international network declares that: “Changing the narrative means not making statements that make the victim or family of the victim accountable for a crime against them.” A second organization, Moving to End Sexual Assault (MESA), uncompromisingly adds: “Any time someone responds to a victim by questioning what they could have done differently, they are participating in victim blaming.”

Of course, the point of these safety memos is not to apportion blame for crimes that have already occurred so much as to publicize best practices for preventing new crimes. It is absurd to propose that furnishing a general audience with actionable advice on safety somehow stigmatizes people who—quite possibly despite their own best efforts—have been victimized. Yes, your car might be stolen even if you lock it and take the keys, but does that mean that no one should remind us to lock our cars and take our keys? Or to use a more timely example, advising people to mask and maintain social distance does not victim-shame those who have already contracted COVID, some of whom no doubt caught the disease despite masking and maintaining distance. Still, the activists suppress.

It’s a kind of punitive narcissism: the condition whereby your desire not to be reminded of your misfortune outweighs my right to be equipped to avoid the same misfortune. But even taken at face value, the activists’ notion that we can never correlate outcomes with predisposing behaviors is an argument that we apply nowhere else in life. Such reasoning negates the eminent behavioristic goal of learning from one’s mistakes. Logically speaking, it also negates entire major fields of inquiry—say, epidemiology, which is wholly dependent on the strategy of cataloging possible causative factors over time and drawing logical inferences about common denominators and outcomes. In most walks of life, it is assumed that growth is an ongoing process of self-reflection: What worked? What didn’t?

Frankly, some of us could use a wake-up call. There are people who got COVID because they didn’t mask or distance or scrub, and it is not inappropriate to hold them up as cautionary tales. A woman is never to blame for a man who beats her, but a woman who shows no discernment in her choice of partners or who fails to act on obvious cues, especially when children may be put in harm’s way, cannot be absolved of all personal responsibility for exposing herself to avoidable risk. You would hope that such a victim would want to scream the subtle danger signs of her “lived experience” from the rooftops to warn others.

Finally, this thinking fails the test of the greater good. UNLV has an enrollment of 28,000. The Bureau of Justice Statistics tells us the national violent crime victimization rate is 379 per 100,000, or 0.38 percent. All things being equal, withholding safety tips from UNLV’s general population diminishes the physical safety of about 27,000 students in order to protect the feelings of 110. Life can be made neither wholly fair nor wholly foolproof. There will be dangerous people and situations, and no small part of adulthood is learning to navigate such risks. The fact that you may do everything right and still end up a victim does not obviate the advisability of trying to do everything right in the first place.