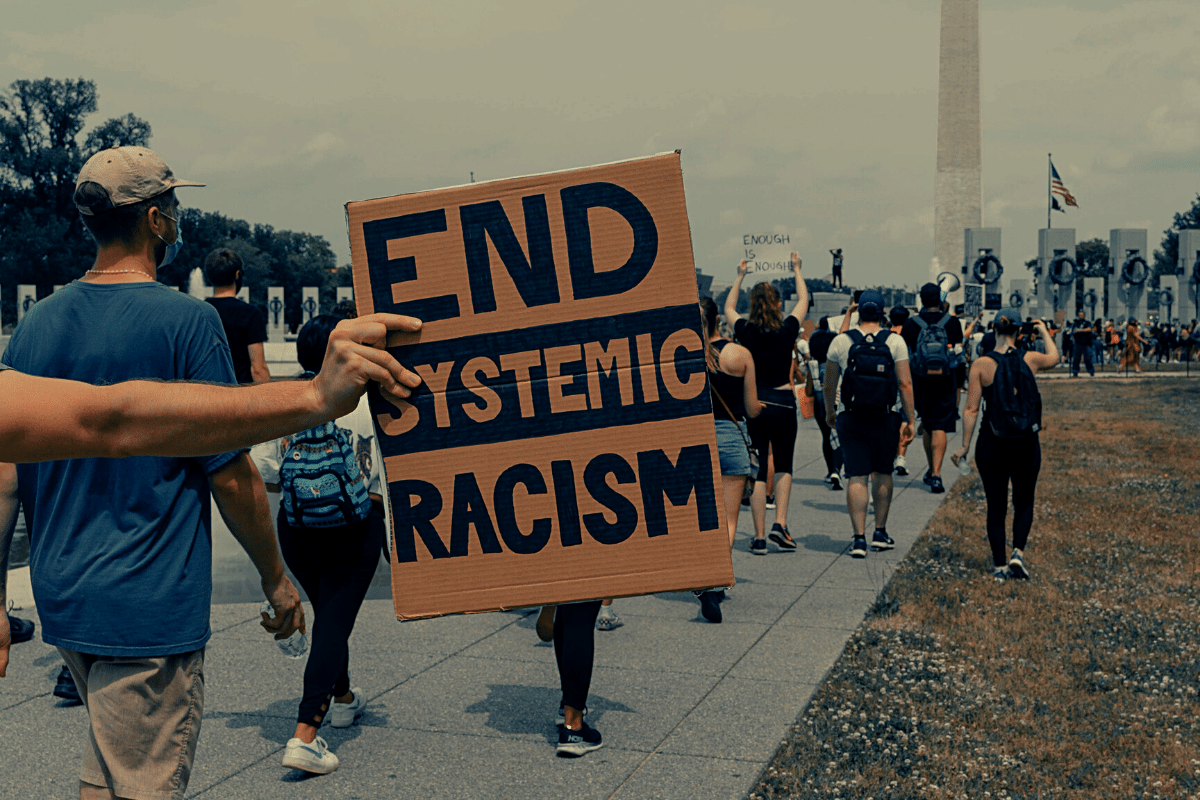

Black Lives Matter

Did the BLM Protests Against the Police Lead to the 2020 Spike in Homicides?

One of the most robust findings in social science is that reductions in effective policing correlate with increases in crime.

Serious crime, particularly murder, soared while everyone was supposed to be locked indoors. Between 2019—by no means a famously peaceful year—and 2020, homicides alone surged by 42 percent during the summer and 34 percent during the fall. Many politically acceptable explanations have been advanced for this, with left-leaning publications like Vox preferring to focus on the undeniable economic devastation wrought by the COVID-19 pandemic. However, an alternative explanation fits the data far better: crime increased because major police departments had their budgets slashed and reeled in their stops dramatically—and similar chaos has followed such “woke” policy moves nearly every time they have been implemented.

The plain fact of the crime surge is a matter of little if any dispute. According to a serious 20-plus page report from the Commission on COVID-19 and Criminal Justice (CCCJ), “homicides, aggravated assaults, and gun assaults rose significantly beginning in late May and June of 2020.” As just noted, murder rates jumped more than 30 percent fall-over-fall and more than 40 percent summer-over-summer from 2019 to 2020. Across just the 21 core cities providing data to the CCCJ project, homicides increased by an astounding 610 between the two years. Further, most other serious crimes of violence were up as well: “Aggravated assaults went up by 15 percent in the summer and 13 percent in the fall of 2020; gun assaults increased by 15 percent and 16 percent.”

Data like these are even more striking when analyzed at the level of each individual city, as can be done via this excellent spreadsheet from Criminologist Jeffrey Asher. In Louisville, the nearest “big” city to my new Kentucky home, homicides had jumped 78 percent when this was recorded by Asher—from 78 in 2019 to 139 in 2020—and his confirmed data for the city dates only to the end of October. Nor was this leap particularly unusual. A scroll through the major urban centers in the Midwestern US reveals surges from 194 to 264 in St. Louis (35 percent) and from 98 to 191 (95 percent) in Milwaukee. Larger American cities followed the same pattern, with famously well-policed New York City seeing an increase from 314 to 437 and my hometown of Chicago witnessing a larger rise from 481 to 748. This last grim tally led all American cities, and seems to have been the second highest total in Chicago during the past two decades.

Multiple theories have been advanced to explain this depressing phenomenon. A December 2020 Vox article from German Lopez headlined “The rise in murders in the US, explained” provides a solid outline of many of them. In it, Lopez presents no less than seven potential explanations for the violence, including chaos caused by COVID-19 (“the pandemic has really messed things up”), secondary medical effects of the bug (“overwhelmed hospitals [could have] led to more death”),1 and the struggling economy. Some of Lopez’s theories are truly innovative: he speculates at one point that “trust in police” could have plunged after high-profile incidents of brutality such as the killing of George Floyd, leading to more “street justice”—and speculates at another that pandemic-purchased guns in the hands of citizens may simply have resulted in “more gun violence.”

Perhaps. Or perhaps something simpler is going on. One of the most robust findings in social science is that reductions in effective policing correlate with increases in crime. And 2020, a year which included the New York Times running a Sunday op ed headlined “Yes: We Mean Literally Abolish the Police,” featured probably the most consistent and sustained attack on the Boys in Blue in the modern era. In New York City, roughly $1,000,000,000 was slashed from the annual police budget, with much of this money shifted to “youth and social services programs,” according to USA Today. Despite noting that these cuts directly caused the cancellation of a 1,200-person class of new officers, scheduled to enter the Police Academy in August 2020, the USA Today piece pointed out that “many say” they were not large enough.

In Los Angeles, similarly, the police budget was reduced by $150,000,000 “following calls to defund the police after George Floyd’s May 25 death.” By November 12th of the past year, these cuts had already resulted in the dissolution of the department’s entire Animal Cruelty Task Force, and more notably of the Sexual Assault/Special Victims unit “that investigated disgraced film producer Harvey Weinstein.” Future LA cuts to “Air Support, the Metropolitan Division, Gangs and Narcotics, and Commercial Crimes” are possible or probable.

Along with axe-cuts to police budgets, 2020 also saw significant and measurable declines in police stops. In Minneapolis, which seriously discussed defunding police and slashed the police budget by millions, Bloomberg noted that the MPD “has been making an average of 80 percent fewer traffic stops each week since May 25.” May 25th, 2020, was the exact date of George Floyd’s death. In addition to routine automobile stops, stops specifically of suspicious vehicles—defined as those thought to have been involved in a crime—were down 24 percent since the same date. Similarly, suspicious person stops “were down 39 percent since May 25.” The Bloomberg piece pointed out that one obvious explanation for this could be “pullback—police reducing their proactive activity in the wake of public criticism of their performance.” Surely so: and data from Chicago and other cities indicate that Minneapolis officers hardly pulled back alone.

Alongside budget cuts and at least city-wide declines in stops came perhaps the ultimate empirical validation of Broken Windows Theory. BWT, the controversial if oft-validated criminological theory originally proposed by James Q. Wilson and George Kelling, argues that visible signs of crime, chaos, and disorder create urban environments that serve as breeding grounds for further and more extreme misbehavior. Throughout 2020, massive and widely tolerated urban riots swept the country. In Minneapolis, where George Floyd died, rioters destroyed much of a famous and heavily minority business district, and set an active police station on fire with the cops initially inside. In Seattle, Black Bloc and Black Lives Matter activists set up a literal city-state known as CHAZ (or CHOP), within which six people were eventually shot. In Portland (OR), the well-known federal courthouse was attacked for roughly 100 days running, often with M-80 fireworks used as home-made mortars.

It is no exaggeration to say that the huge majority of rioters were essentially given the unpunished “room to destroy” originally suggested by Baltimore Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake during her city’s 2015 riots. Empirical articles from sources such as Court-House News and Pamplin Media Group have pointed out that roughly 91 percent of arrested Portland rioters were never prosecuted for anything, and these figures frankly seem similar across other major cities like Chicago. It seems logically obvious that even crimes as serious as murder could occur with relative impunity in this environment: the majority of the attackers of the six people seriously or fatally shot inside CHAZ are still at large.

“Common sense” aside, considerable statistical evidence indicates that the chaos-and-pullback explanation for the 2020 American totentanz fits the data better than alternative hypotheses such as our economic downturn. First, the relationship between crime and poverty (if that even is the proper causal direction) is far trickier than often supposed, and rates of serious crime such as murder frequently do not increase during recessions and depressions. During the recent Great Recession, murders totaled 16,422 in 2008, 15,399 in 2009, 14,772 in 2010, and 14,661 in 2011—declining by 1,761 between the start of the crisis and the commonly used end date for it.

Data specific to 2020 provide further support for non-economic explanations for the murder surge. While homicides, aggravated assaults, and gun crimes all increased dramatically, crimes focused purely on obtaining money all decreased in frequency during a heavily locked-down year. The CCCJ authors note that: “Residential burglary, larceny, and drug offense rates dropped by 24 percent, 24 percent, and 32 percent from the same period in 2019.” Perhaps most significantly, crime data is tracked on a monthly as well as annual basis, and—as previously cited Minneapolis figures indicated—the largest 2020 increases in violent crime trace directly to the Riot Summer following the death of George Floyd, rather than to the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic. Again as per the CCCJ report: “Homicides… rose significantly beginning in late May and June of 2020.”

This finding gels perfectly with recent history. The increase in murders from roughly 14,000 in 2014 to 17,294 in 2017, following the first wave of Black Lives Matter-associated riots and the resulting police pullback, gained international attention as the “Ferguson Effect.” More broadly, US murders jumped from 8,530 in 1962 to 24,700 in 1991, following a generation or two of criminal justice reforms including the Miranda and Escobedo protocols, the Fruit of the Poisoned Tree doctrine, and a general liberalization of sentencing policies. Other serious violent crimes jumped proportionately, as detailed by Mona Charen in the unfashionable but essential book Do-Gooders. In a sentence so obviously true that only an academic social scientist could deny it, more police policing more effectively decreases crime.

And crimes have victims. While I mourn for dead fellow citizens of any color, a sad and absurd reality of both post-Ferguson and summer 2020 violence is that a great many of those killed unnecessarily were black Americans. In Chicago, 81.8 percent of those murdered in 2020 were African Americans, while 3.9 percent of victims were white. The simplest possible sort of number-crunching shows us that, assuming consistent rates of homicide by race, the Windy City’s vertical move from 481 to 748 deaths by violence cost 218 black lives inside one year. Assuming that murders nationwide increased only by 35 percent from 2019’s total of 16,425 and that only 50 percent of these new victims were black, the equivalent toll country-wide would be 2,874 dead black folks, including horrifying victims such as hero cop David Dorn and little eight-year-old Secoriea Turner.

The numbers speak for themselves. The ideas advanced by Black Lives Matter may be popular and “woke,” but they are also very often the worst possible policies for those of us who actually want to preserve black, and other, American lives.

Note:

1 Additional content in parentheses here is mine.