Books

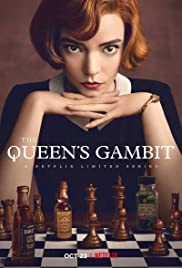

The Hustler and the Queen

NOTE: This essay contains spoilers.

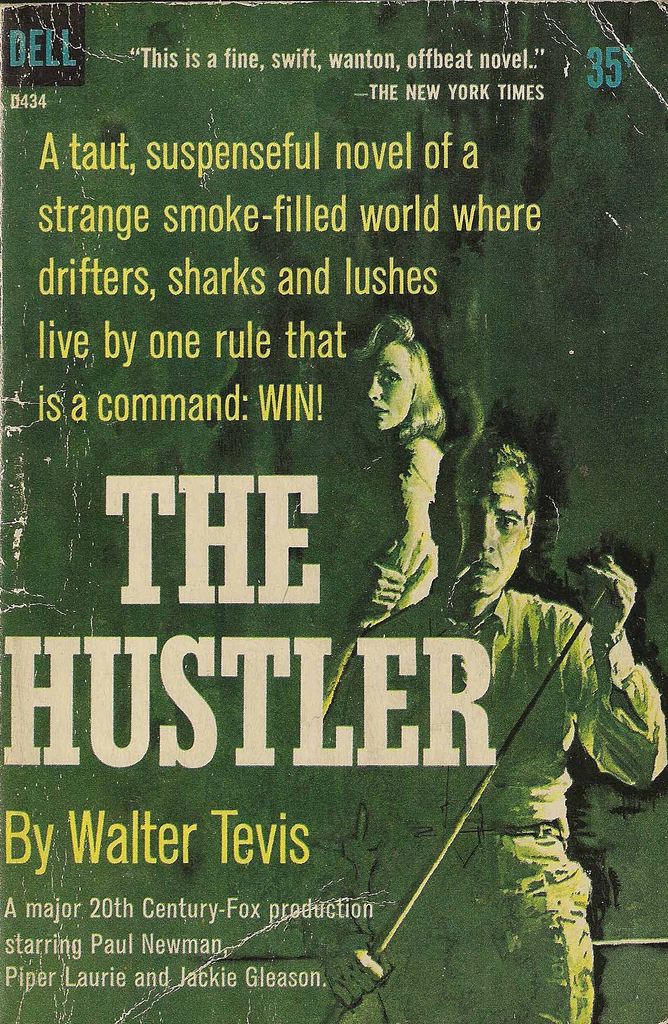

The surprise success of the Netflix miniseries The Queen’s Gambit has brought me a great deal of delight—I’m a longtime fan of both the novel and its author, Walter Tevis. Just this summer, I wrote an essay about all the great American popular novels I wish I’d written myself, and the first book I mentioned was Tevis’s 1959 masterpiece The Hustler. But while The Hustler may be Tevis’s best book, The Queen’s Gambit has always been my favorite. I’ve never been anything but an incompetent at the pool table, but for a brief shining hour I was a chess prodigy. In July of 1968, a few weeks before my 10th birthday, I competed in a state chess tournament at the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry, in my hometown of Portland, Oregon, and won the prize for Best Fourth-Grade Boy. This triumph—my first and only triumph at anything—survives online in the archives of Northwest Chess magazine.

Usually when a high-profile film or TV series is adapted from the work of an under-appreciated writer, that writer enjoys a brief spell of renewed attention and interest as magazine profiles proliferate extolling his virtues and lamenting the fact that he has latterly fallen into obscurity. For instance, the success of Stephen Frears’s 1990 film The Grifters brought the work of pulp-fiction maestro Jim Thompson, who had died 13 years earlier, back onto the cultural radar. And in 1999, when Anthony Minghella adapted The Talented Mr. Ripley it brought some well-deserved posthumous attention to the talented Patricia Highsmith.

Alas, no such outpouring of Walter Tevis profiles seems to have accompanied the release of Scott Frank’s adaptation of The Queen’s Gambit. This is a shame. Tevis smoked and drank to excess, and died on August 9th, 1984, at the age of 56. Like their creator, most of Tevis’s protagonists suffer from one sort of addiction or another. Even the alien protagonist of The Man Who Fell To Earth (adapted by Nicolas Roeg into a 1976 film starring David Bowie) becomes an alcoholic. Fast Eddie Felson, the protagonist of The Hustler, allows alcohol to cloud his judgment and, occasionally, derail his career as a pool hustler. And Beth Harmon, the protagonist of The Queen’s Gambit, is addicted to pills and alcohol. Fortunately, she appears to be on her way to conquering those addictions by the end of the miniseries, but this raises questions about what ought to happen if Netflix decides to commission a second season. Personally, I hope there is no second series. After all, Tevis never wrote a sequel to his novel (he died a year after the book’s publication). But no pop-cultural product as popular as The Queen’s Gambit (it’s been viewed in more households than any other scripted Netflix miniseries) ever goes without a sequel.

However, Tevis did write a sequel to The Hustler, and The Hustler tells much the same story as The Queen’s Gambit. In both books, a young whiz kid who excels at a difficult game must battle inner demons and a wicked substance-abuse problem in order to rise to the top of his/her field. Each prodigy then runs up against an apparently immoveable object in pursuit of greatness. For Fast Eddie Felson, that object is George Hegerman, aka Minnesota Fats, a corpulent pool hustler who Eddie can’t ever seem to beat. For Beth, the immoveable object is Soviet chess champion Vasily Borgov. In the final chapter of The Hustler, Eddie does finally manage to defeat Fats, and win five thousand dollars in the process ($45,000 adjusted for inflation). And Beth eventually dethrones Borgov at a tournament in Moscow. Both Eddie and Beth end their respective novels at the height of their powers having defeated their respective nemeses.

But Tevis suggests that neither is likely to find lasting happiness in his or her chosen sport. At the end of The Hustler, Eddie realizes that, if he wants to continue making a living hustling pool, he will have to kick back a large share of his winnings to the mafia-like cartel that controls big-time pool hustling in the US. In The Queen’s Gambit, during a tournament in Mexico, Beth finds herself competing against a 12-year-old Soviet chess prodigy named Georgi Petrovitch Girev. He tells Beth that his plan is to be world champion at the age of 16. If you succeed, Beth asks him, “what will you do afterward?” Girev is nonplussed—he is so focused on becoming world champion that he can’t even fathom trying to accomplish anything else in life. But Beth seems to realize what Girev does not—that reaching the top of your profession at an extremely early age means you can only go back down again. Chess cannot be the entirety of her life.

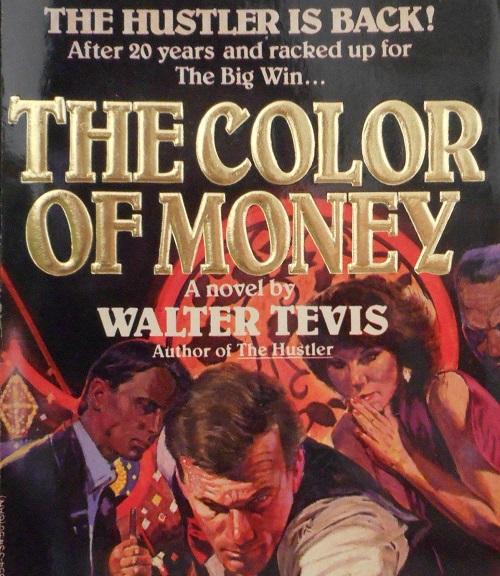

If he does decide to forge ahead with a second series, writer-producer-director Scott Frank should take a look at what happened to Eddie Felson in The Color of Money. Chess and pool may not seem to be similar games, but they actually have a lot in common. And in both The Hustler and its sequel, Tevis makes explicit the similarity between the two. In The Hustler, written decades before Beth Harmon was even a glint in her creator’s eye, Tevis described billiards as “a chesslike game, depending on brains and nerve and on knowing the tricks.” In the sequel, published a quarter-century later, he writes about an aged African American pool hustler who “played position by moving the cue ball around as though it were a chess piece to set where he wanted it.” From this man, Eddie “learned to make his own chessman of the cue ball.”

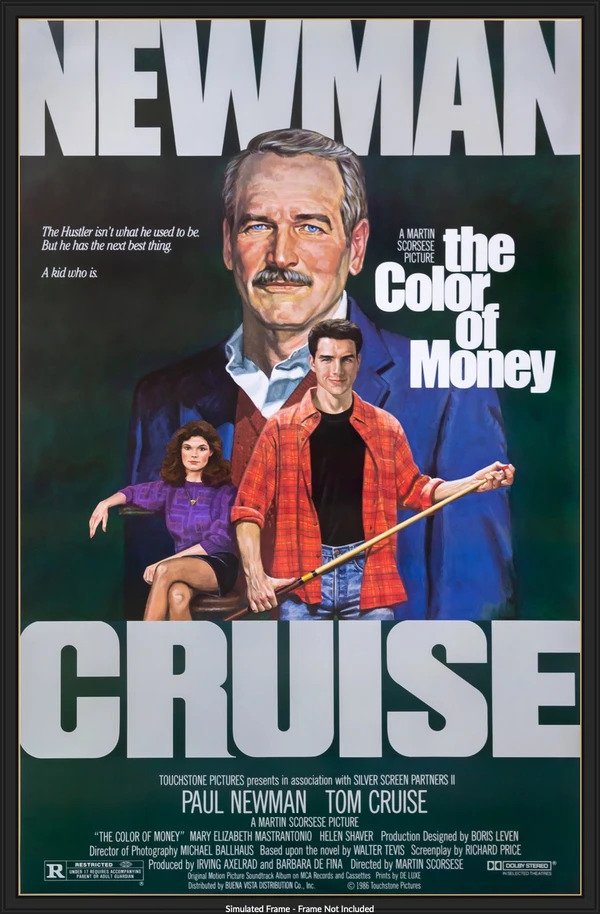

Published just a year after The Queen’s Gambit, The Color of Money is best remembered today as the source of the 1986 Martin Scorsese film of the same name, which starred a 61-year-old Paul Newman (reprising the role of Fast Eddie Felson that he created in Robert Rossen’s 1961 adaptation of The Hustler) and Tom Cruise (fresh from his star-making turn in Top Gun, released earlier the same year). But Scorsese’s film bears little resemblance to the novel on which it is based. Tevis wrote a script, but Scorsese threw it out and commissioned a new script from novelist and screenwriter Richard Price. Price’s script is a good one but it provides no real blueprint for Scott Frank.

In Scorsese’s film, Fast Eddie’s hustling career is decades behind him. Now just known as Ed Felson, he is a traveling liquor salesman, apparently stationed in Chicago. He has a fairly casual romantic relationship with a woman (played by Helen Shaver) who owns a bar/pool hall. One night Eddie watches a young hustler named Vincent Lauria (Cruise) demolishing another young hustler (played by John Turturro) in game after game of pool and detects a financial opportunity. Vincent has plenty of natural talent but no discipline. His girlfriend Carmen (played by Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio) acts as his manager, setting up games and handling the money, but she knows very little about pool hustling. So Eddie sidles over and ingratiates himself with Carmen. Soon, he has agreed to finance a trip across the country to Atlantic City where Vincent will compete in a high-stakes nine-ball tournament. Eddie will put up all the money in exchange for 60 percent of Vincent’s winnings. At this point the film becomes a road picture (as well as a bit of a buddy picture), as the threesome drive across the Midwest, stopping at pool halls in every town they pass through. Eddie teaches Vincent how to be a pool hustler and—when the hustle upsets some hotheaded loser who feels he has been conned—how to beat a hasty retreat out of town.

Like the New Yorkers they are, Scorsese and Price treat the American Midwest like flyover country. Every town in the film looks exactly the same. If we were in New York, every restaurant and boulevard would have its own personality, but in Scorsese’s film the long road from Chicago to Atlantic City seems to run through nothing but nondescript American nowheres. This makes artistic sense. When Eddie visits a city, he doesn’t do any sightseeing; he’s interested only in the pool halls, and he visits them mostly at night, having slept all day. And Tevis’s own work emphasizes the sameness of various mid-sized American cities. In The Hustler, when Eddie and his financial backer Bert first drive into Lexington, Kentucky, Tevis writes: “Downtown Lexington could have been downtown anywhere—all men and glass and traffic.” Similarly, in The Queen’s Gambit, while accompanying Beth to a tournament in Mexico, her stepmother Mrs. Wheatley mentions that her lover du jour has gone off to Oaxaca on business. “I’ve never been to Oaxaca,” Mrs. Wheatley remarks, “but I suspect it resembles Denver.”

In Scorsese’s film, as the threesome head east, the sexual attraction between young Carmen (Mastrantonio was 28 when the film was released) and Eddie grows, igniting Vince’s jealousy and anger. And, somewhat improbably, by the time they all arrive in Atlantic City, Eddie has regained his pool-playing skills of yore and eventually finds himself competing in the championship match. This is, I suppose, the dream of many a middle-aged American man: to regain the skills of his youth in the presence of a woman half his age who is clearly attracted to him, and to find himself on the brink of winning a fortune. Newman suffers a painful personal humiliation in the third act, but his final line is a triumphant, “I’m back!” It’s a nuanced and bittersweet ending, but the story’s general trajectory bears little relationship to what life is actually like for American men long past their physical and professional prime.

Tevis’s novel, on the other hand, reckons realistically with Eddie’s fate. Vincent and Carmen don’t appear in the novel; they were invented by Price. In the novel, Eddie is 50 years old and has been the owner and operator of a small pool parlor in Lexington for the last 22 years. As the story opens, Eddie and his wife, Martha, have just divorced. The divorce has nearly wiped him out financially and he has been forced to give up the pool hall. Soon, however, a little bit of luck comes his way. A small start-up television production company approaches Eddie and offers to pay him to play a series of exhibition matches in a variety of Midwestern American cities against his old nemesis, Minnesota Fats, for $800 a pop. The money isn’t much, but the production company is hoping it can sell the series to ESPN or ABC Sports, which would mean a lot more money for Eddie and Fats. Eddie can’t afford to turn down the opportunity. But Fats is rich and retired and living in Miami so he pretends not to be all that interested. He tells Eddie he’ll join the project only if he is paid $1,000 per exhibition game. Eddie explains that the production company can’t afford any more than $800. That’s fine, Fats tells him, you can pay me the other $200. Eddie realizes that once again he has been out-hustled.

Eddie hasn’t played pool competitively in 22 years and his first few matches against Fats result in embarrassing losses. Among Eddie’s numerous handicaps is that fact that his vision is weak but he is too vain to wear glasses. Eventually he decides that getting thrashed on TV is more embarrassing than wearing spectacles, so he buys the glasses and they improve his pool game immensely (Scorsese gestures at this story element briefly in the film). After losing the first two exhibitions badly, Eddie gets progressively better in matches three, four, and five, losing them all by ever-smaller margins. He is improving so rapidly, in fact, that he feels confident that he’ll be able to beat Fats in the final exhibition, which is to be held in Indianapolis. When Fats doesn’t show up at the venue, Eddie goes to his hotel to look for him and finds the enormously obese man sitting up in bed, dead (this scene mirrors the scene in which Beth Harmon finds Mrs. Wheatley dead).

Although it didn’t do much for his financial situation, the TV gig has given Eddie a shot of confidence. Soon he finds himself wooing and winning a gorgeous 40-year-old divorcee named Arabella. She was, for years, a faculty wife, married to a hotshot professor at the University of Kentucky. Eddie, who never went to college, is generally intimidated by university-educated people. What’s more, Arabella is English and speaks with a posh accent, something that Eddie, a hick from Oakland, CA, finds even more intimidating. But his newfound status as a (very low-level) TV performer gives him the courage he needs to make a good impression on her. University-educated herself, she makes a living editing the writings of academics who hope to place their work in prestigious journals. Since moving to Kentucky with her now ex-husband, she has also become enamored of Kentucky folk art, and written about it for a few small academic journals.

As they cruise the Kentucky back roads together on their days off, Arabella tries to get Eddie interested in the folk art of the Bluegrass State. At first, he is mostly bored by it. At one point they stop at some hillbilly’s roadside sculpture garden and wander around among a bunch of primitive sculptures made from old car parts and other found items. Arabella falls in love with two of the sculptures. Eddie pays $250 apiece for them, which he thinks is highway robbery. But, a few weeks later, when he learns that Arabella has sold one of the sculptures to a wealthy Lexington art collector for $1,200 Eddie starts to see Kentucky folk art in a new light. He doesn’t care much about art, but he loves a good hustle. Suddenly the idea of driving around rural Kentucky and buying woodcarvings, handmade quilts, and metal sculptures from a bunch of dirt-poor hicks and reselling them for a huge profit to various big-city suckers (i.e., folk-art collectors) strikes Eddie as almost as much fun as shooting pool for a living.

And so, after using nearly every last penny they have to purchase Kentucky folk art and set up a high-end gallery in downtown Lexington, Eddie and Arabella find themselves, much to their own astonishment, running a small but profitable and very prestigious local business. Alas, a disaster nearly destroys it, after which Eddie and Arabella find themselves in need of some quick cash. That’s when Eddie hears about an upcoming nine-ball tournament in Lake Tahoe, Nevada, the top prize of which is $30,000. And so off he goes, with Arabella’s blessing, in search of one last opportunity to make money with his pool cue. (It is curious that Scorsese, who was born in New York City, sends Eddie east in pursuit of his dreams, while Tevis, who was born in San Francisco, sends him west).

And it is here, in the story of Eddie and Arabella, that Scott Frank might find a continuation of Beth Harmon’s own story. Not only does Beth bear a strong resemblance to Eddie, she also bears a resemblance to Arabella. Neither Beth nor Arabella originally chose to live in Lexington. Beth was taken there by the man and woman who adopted her. Arabella followed her husband there when the university offered him a job. After the death of her stepmother, Beth could have moved anywhere. But she seems to have a stubborn allegiance to the city where she went to high school. After her divorce, Arabella could have moved anywhere, but she too seems to have grown fond of Lexington, indeed of all of Kentucky. Arabella is 40 years old in 1983, meaning she was born in 1943. Beth appears to have been born in the late 1940s or early 1950s. Both seem to have more intellectual power than most of the men in their lives.

Beth doesn’t want to end up a one-trick pony like poor Georgi Girev. She is intellectually curious and probably wouldn’t be happy spending the rest of her life on the professional chess circuit. And though she has much in common with Eddie, she doesn’t seem to share his lust for money. While Scorsese’s Fast Eddie seems motivated more by a love of competition than a love of money, Tevis (who knew plenty of financial insecurity in his lifetime) created a Fast Eddie who proclaims his love for money unapologetically. As Eddie makes the transition from pool hustler to art dealer, Tevis writes:

It did not seem crazy, or even strange, for him to be doing what he was doing. Art had never meant anything to him, and he had never been in an art gallery or museum in his life. But what he was doing felt like a hustle and he liked the notion of a hustle, liked putting his mind into it. It was in the service of money, and he loved money—loved dealing with it, loved making it, using it, having a dozen or more large denomination bills, folded, deep in his pocket. So much in his life did not make sense. But money did.

In the high-class world of fabulously successful artists like Martin Scorsese and Richard Price, anyone who loves money is always portrayed in a negative way. But to a middle-aged man who’s never had enough of it, a love of money is perfectly understandable, and not to be disparaged. Tevis understood this.

Fortunately for Beth Harmon, however, Tevis didn’t burden her with this craving. She seems perfectly happy with her Lexington tract home and her modest earnings. Perhaps she’ll leave the world of competitive chess and enroll as a student at the University of Kentucky, where she’ll major in math, or statistics, or game theory. I can see her following in Arabella’s footsteps and marrying a professor at UK. Perhaps she’ll be luckier than Arabella. Perhaps her marriage will be a real love match. But Frank will eventually have to throw some sort of financial catastrophe in the path of Beth’s happiness. When this happens, Frank can send her out, like Fast Eddie, to search for an infusion of quick cash in the only venue she really knows much about—the competitive chess circuit.

Such a development would bring her back into contact with many of the great characters she encountered in season one: Borgov, Girev, Benny Watts, and all the others. Or perhaps it will be one of Beth’s good friends—Jolene, Townes, Harry Beltik—who finds himself in trouble and in need of money that only Beth has the ability to make in a hurry. Perhaps the Methuen Home For Girls (the orphanage in which Beth and Jolene were raised) will find itself targeted by a well-heeled real-estate tycoon who wants the land it stands on for a massive casino he plans to build there. I’m happy to let Scott Frank work out the details. But he ought to at least take a look at the roadmap that Tevis left behind in the pages of his sequel to The Hustler. And he should not allow himself to be seduced by Martin Scorsese’s adaptation. It’s an excellent movie but fundamentally unfaithful to Tevis’s original concept of Fast Eddie.

The one thing Tevis did that Frank can’t do was to jump forward 20 years in the life of the story’s main character. While it might be nice to see what an Amy Adams or Christina Hendricks might be able to do with a 45-year-old version of Beth Harmon, that won’t happen. Two-thirds of the fun provided by Netflix’s The Queen’s Gambit was provided by the performance of Anya Taylor-Joy. No one in their right mind would want the series to continue without her. But whichever way Frank takes the series in season two, one thing is certain: He has turned Tevis’s once sadly neglected novel into a very hot commodity. In November of 2019, I purchased a first edition of The Queen’s Gambit that had been signed by Walter Tevis. I paid $20 for it on the American Book Exchange website. Currently, the cheapest unsigned first editions on ABE are listed for more than a thousand dollars. So it seems that Fast Eddie isn’t the only one with an eye for a good investment.