Art

Commemorating Mary

Wollstonecraft and her daughter Mary each paid a high price for defying convention. They both entered into relationships out-of-wedlock at a time when doing so was enough to put a woman out of good society.

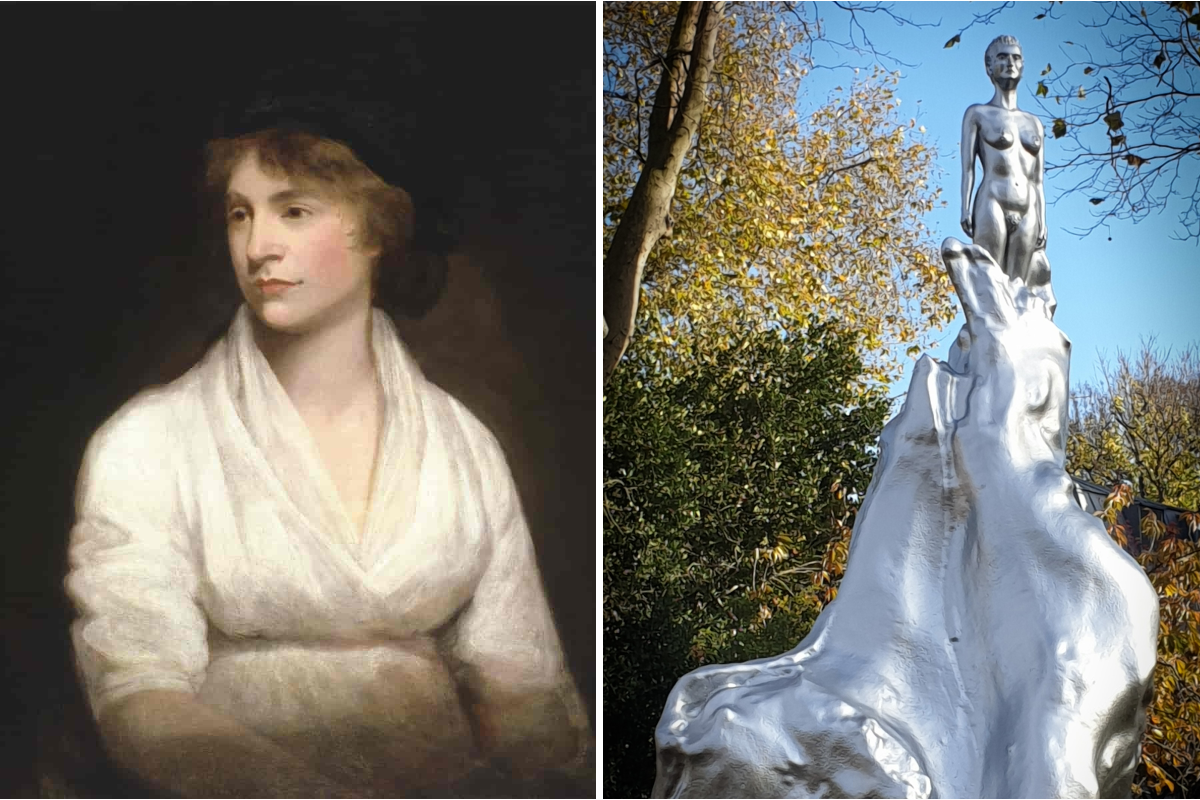

I’ve seen several interesting discussions about the controversial new Mary Wollstonecraft sculpture recently unveiled at Newington Green, the London community where the pioneering feminist briefly operated a school for girls. On the whole, I have seen more criticism than praise. Rachel Cooke of the Guardian called the little female figure at the top of the sculpture, “A Pippa doll with pubic hair.”

A few reviewers have praised the sculpture and taken a faintly condescending tone toward philistines like me who don’t “get” it. “[M]ight [the nudity] be understood as a metaphor for Wollstonecraft’s vision of personal authenticity?” asks Eleanor Nairne in the New York Times. She describes the controversy as a “fuss,” and points out that there is a full-length statue of Wollstonecraft’s son-in-law, Percy Bysshe Shelley, in Oxford, which leaves nothing to the imagination. Nudity in pubic—pardon me, public art—is part of our Western cultural tradition, surely.

An article by scholar Vic Clarke posted on the History Workshop website at least corrects the common misconception that the little naked woman emerging out of the big silver whoosh is a representation of Wollstonecraft. It is supposed to be Everywoman. She writes: “If this work is not of Wollstonecraft, but ‘for’ her, as [the sculptor Maggi] Hambling asserts, we must question to what extent this art object is attuned to Wollstonecraft’s work and legacy.”

Now, I’m no expert on how to cast a statue, but I find this one clumsy, badly proportioned, and Everywoman’s neck to be too long for her body. But the nude is only a small part of the sculpture. News photographs that focus on the tiny figure and crop out the rest give a misleading impression of the overall proportions—the naked female is the size of a Barbie doll, and she is sticking out of an irregularly shaped silver wave. In an interview, Hambling has confirmed that the wave represents a “tower of intermingling female forms.” It sits on a plinth which features a quote from Wollstonecraft: “I do not wish women to have power over men; but over themselves.”

The sculpture is not large; five men carried it from a delivery van and stuck it onto its plinth, after some other men had dug the hole for it, poured the cement, and set it into place. The runner-up for the sculpture design was also a man, but his design was not chosen. The “Mary on the Green” committee who raised funds for 10 years, who issued the call for design proposals, who short-listed the submissions, and who awarded the commission to Hambling, have put their best face on the controversy. “We are so grateful,” they tweeted unconvincingly, “to everyone who has thoughtfully engaged with ‘A Sculpture for Mary #Wollstonecraft’ over the past couple of days: it’s fantastic to see so many people talking about this incredible woman who, for far too long, was written out of history… The diversity of views [about the sculpture], openly expressed, is just what Mary #Wollstonecraft would have loved.”

🧵 We are so grateful to everyone who has thoughtfully engaged with 'A Sculpture for Mary #Wollstonecraft' over the past couple of days: it's fantastic to see so many people talking about this incredible woman who, for far too long, was written out of history.

— Mary on the Green (@maryonthegreen) November 11, 2020

The views are indeed diverse. Dislike of the statue crosses ideological lines. Pearl-clutching prudes don’t like it, and Vic Clarke spoke for a number of Twitter feminists when she objected that, “the decision to present her unclothed makes her the subject of a sexualised gaze.” Others chimed in, wondering if Everywoman ought to have obviously Caucasian features, a taut midriff and perky breasts? Not to mention such an ostentatiously hairy pudendum. What we are looking at is a naked human, a female mammal, with her genitalia clearly displayed. And this emphasis is the key to the central tragedy of Wollstonecraft’s life: She was born at a time when being a female human, a mammal, determined your destiny.

I first encountered Wollstonecraft’s writing at university more than 40 years ago, so I’m bemused to see people claiming that she has been “written out of history.” This phrase implies some kind of sinister plot. Perhaps it was the Stonemasons or something. The usual explanation is that a posthumous biography of Wollstonecraft so shocked British sensibilities that no respectable woman would read her for almost a century, revealing as it did her love affairs (including an unrequited obsession with the married painter Henry Fuseli), her illegitimate daughter, and her suicide attempts.

More recently, I have read Charlotte Gordon’s dual biography of Wollstonecraft and her daughter Mary Shelley. Wollstonecraft’s father was a feckless brute and an alcoholic, and she was a rebel from her earliest days, intervening to protect her mother from her father’s drunken assaults. She had every reason to resent the unequal treatment she received as a daughter, compared to the oldest son. In addition, thanks to her father’s poor handling of his finances, the family slid from middle-class gentility into poverty. After her parents died, Wollstonecraft took on the life-long responsibility of supporting her two younger sisters.

Wollstonecraft was a pioneer in more ways than one. She ought to be the patron saint of academics who see the vocation of teaching as an opportunity to preach social justice to their impressionable charges. After her own school for girls in Newington Green failed, Wollstonecraft took a position as governess to the daughters of a very rich, very titled family in Ireland, the Kingsboroughs. Wollstonecraft despised her wealthy employers, particularly Lady Kingsborough, and made it her mission to instill her pupils with republican ideas. She took them on walks to see the appalling conditions in which the Irish peasantry lived. She made it clear that feminine accomplishments such as needlework were frivolous and stupid. And she took pleasure in the fact that the girls grew fonder of her than they were of their formidable mother.

Within a year, Wollstonecraft was unable to hide her contempt for Lady Kingsborough; they quarreled openly, and she was fired. She had made an indelible impression on the minds of the three daughters and Lady Kingsborough rued the day she hired Mary Wollstonecraft. In later years, one daughter left her husband and moved to Italy with another man, taking the name of Mrs. Mason, a fictional character created by Wollstonecraft. She credited her governess with freeing “her mind from all superstitions.” Another daughter had a child out of wedlock and during the resulting scandal, an anonymous letter to the Gentlemen’s Magazine suggested that this was the “natural consequence” of Wollstonecraft’s baneful influence.

But all that came later. First, Mary Wollstonecraft went to live in revolutionary France. She flouted the religious and social conventions of her day by taking a lover, Gilbert Imlay, an American involved in shady financial doings. And there, Mary ran into the facts of 18th century life: She had a daughter out of wedlock and Imlay abandoned her. She returned to England and attempted suicide, throwing herself off Putney Bridge into the Thames. A man pulled her out of the water.

There was virtually no way for a gentlewoman in those days to earn enough money to support herself, let alone a baby, plus hire the servants needed to take care of her household. Nevertheless, Mary Wollstonecraft found a way. She did it by writing editorials and by doing translation work. According to Charlotte Gordon, recent Wollstonecraft scholarship has uncovered the subversive changes that Wollstonecraft inserted into a children’s book by a German author. She deleted “sentimental effusions about family life” and freely interposed her own opinions. “Sometimes she even omitted entire passages, inserting in their place her own treatises on the evils of female fashion and the importance of a good education for girls.”

Wollstonecraft’s first big success was her swift and vehement response to the publication of Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France. Her refutation of Burke’s defense of tradition sizzles with indignation, sarcasm, and ad hominem attacks. When her authorship became known, the writer and Whig politician Horace Walpole condemned her as a “hyena in petticoats.” She is now best remembered for her Vindication of the Rights of Woman, published in 1792, and today regarded as the most important of the early feminist manifestos. In an age in which writers claimed that Woman’s power and influence lay in her vulnerability, her sweetness of temper, and her ability to charm, Wollstonecraft countered: “My own sex, I hope, will excuse me, if I treat them like rational creatures, instead of flattering their fascinating graces, and viewing them as if they were in a state of perpetual childhood, unable to stand alone.”

A few years later, Mary found love again with the radical philosopher William Godwin. Godwin, an anarchist (just think of the lyrics of John Lennon’s “Imagine,” and you’ll have Godwin in a nutshell), regarded marriage as unnatural. He was more of a puritan by nature than a libertine, but he was known as an advocate for Free Love. When Wollstonecraft became pregnant, they got married to protect her reputation and their child’s future, and Godwin apologized to their radical friends for his backsliding. During their short-lived marriage, he rented a separate apartment so he could write in peace, coming home for dinner to be with Mary and her daughter Fanny. The servants carried their notes to each other during the day.

Mary Wollstonecraft delivered her second child, the future Mary Shelley, on August 30th, 1797. She died 10 days later, at the age of 38. Had she lived, it is likely that tensions would have arisen in her marriage, because her husband could walk out the door and go to his writing retreat, mentally, emotionally, and physically unencumbered by child-rearing and housekeeping, while Mary could not. This difference between men and women and what it means for careers and for self-fulfillment is still a huge area of contention in modern times.

When I was in university in those long-ago days, we also studied Shulamith Firestone, a radical feminist who took this dilemma to its logical conclusion: For men and women to be truly equal, she argued, women must overcome their mammalian selves. Daycare was not enough, because pregnancy itself was “barbaric.” Women were always at the “continual mercy of their biology,” therefore, to be liberated, human reproduction must occur in artificial wombs, and child-rearing must be a collective, paid, enterprise. These proposals, obviously, never caught on. The vast majority of women rejected the radical vision because there were many things about femininity (Hallmark Christmas movies, stiletto heels, decorative throw pillows, getting the men to dig holes and carry heavy statues) that they liked and didn’t especially want to give up.

In my university class, it was stressed that Mary Wollstonecraft died from an infection because the doctor who attended her after the birth hadn’t washed his hands. We were expected to take this as another indictment of the patriarchy. But my feminist professors did not convince me entirely. I concluded that the tragic facts of Wollstonecraft’s life were not so much because of the patriarchy as the consequences of being a female human mammal in the 18th century. Sex leads to babies. Childbirth, in those days, was often fatal. Babies require years of nurture. I couldn’t blame men for this. Having and rearing children means your full energies cannot be directed toward (1) making a living or (2) fulfilling yourself spiritually or intellectually. But how many 18th century men fulfilled themselves? I viewed the dilemma through a biological and economic lens, not an ideological one.

Wollstonecraft and her daughter Mary each paid a high price for defying convention. They both entered into relationships out-of-wedlock at a time when doing so was enough to put a woman out of good society. Legend has it that 16-year-old Mary Godwin gave herself to Percy Bysshe Shelley at her mother’s tomb. Both mother and daughter had illegitimate children. Mary Wollstonecraft’s daughter by her faithless lover Gilbert Imlay committed suicide. Godwin believed Fanny Imlay killed herself out of unrequited love for Percy Shelley. From the time young Mary ran away with Shelley, she was at the whim of his caprices, his sudden removals from here to there, his mishandling of their limited funds. Arguably, this peripatetic lifestyle helps to account for the early deaths of three of their four children. By defying convention, both mother and daughter endured great suffering and hardship, including financial hardship.

I am frankly amazed at the hatred of capitalism prevalent among modern scholars of the Romantic period. A washing machine, a refrigerator, birth control pills, and modern hygiene would have liberated Mary Wollstonecraft—and her female servants—from daily drudgery, freeing them all to follow their own pursuits. A robust economy provides the wherewithal for a welfare state, which has so thoroughly ameliorated the consequences of illegitimacy that almost half the babies born in England today are born outside of wedlock. The controversy around the Wollstonecraft sculpture has reportedly led to a flood of donations for statues commemorating other eminent women—meaning that women today have money to spare on causes that are important to them.

But Mary Wollstonecraft was a woman who struggled to rise above the fact of her biology, the fact of being a woman, the fact of being a mammal. And that is why I dislike Hambling’s statue. Wollstonecraft is represented by Everywoman, and who is Everywoman? A naked ape, a mammal. A Mary Wollstonecraft sculpture should represent struggle—even anger. It should represent her belief that women were—and should be regarded as—rational beings with intellects. But the tiny silver female emerging from the silver wave, the “tower of intermingling female forms,” was, in real life, caught by that wave and dragged to her death. It is Mary Wollstonecraft’s intellect and struggle we should be commemorating and celebrating, not her physical being.