Top Stories

Against an Unequivocally Bad Idea

Universal Basic Income, or “UBI,” is a proposal to give every American a periodic check from the government.

I first heard the phrase “Universal Basic Income” when I was sitting in a Wesleyan sociology class. My classmates and I were discussing the American safety net, and one student proposed eliminating the whole system. “The safety net has so many programs, and to be honest, I don’t really understand them,” he said. “I’d rather just replace them with a UBI.” A few students concurred, and a short debate ensued.

Universal Basic Income, or “UBI,” is a proposal to give every American a periodic check from the government. Everyone would receive the same amount, no strings attached. Although my classmate’s proposal had a certain cool-kid hipness to it, I was appalled. The current safety net does a tremendous amount of good, lifting millions of low-income people out of poverty every year. The fact that it isn’t easily understood by undergraduate sociology majors was pretty low on my list of concerns.

After class ended, I largely forgot about our discussion. No mainstream politician was openly supporting UBI, and the impending rollout of something called “Obamacare” was dominating the headlines. UBI was just a fashionable idea at academic cocktail parties. But UBI has since gone mainstream. Andrew Yang based his presidential bid on the idea that all Americans should receive monthly $1,000 checks from the government, and similar proposals have been made by journalists and think tank analysts. UBI even enjoys some degree of bipartisan support, drawing fans from both sides of the political aisle.

But the bipartisan appeal is a façade. Liberals and conservatives support radically different versions of UBI, and both are fatally flawed. The liberal version of UBI is unworkable, and the conservative version would throw millions into poverty. Regardless of how one tinkers or modifies the details, UBI is an Unequivocally Bad Idea.

The liberal version of UBI

Liberals tend to support existing anti-poverty programs. As such, they would fund a UBI not by cutting spending, but by raising taxes. To see why this is flawed, we need to understand two concepts from labor economics: substitution effects and income effects. People are more willing to work when they are offered higher wages. You are probably unwilling to do certain jobs for $20 per hour; but if employers instead offer $40 per hour, you may change your mind. Economists call this the substitution effect: people are only inclined to substitute an hour of work for an hour of leisure when their pay is sufficiently high.

But that’s just one avenue through which pay affects work. The other is the income effect: many people want to achieve a certain level of income, and they work however many hours will give them that income. For example, if someone aspires to earn $60,000 per year no matter what, they will work fewer hours when given a higher hourly wage. When it comes to tax policy, economists generally believe that the substitution effect dominates the income effect—in other words, higher taxes discourage work.

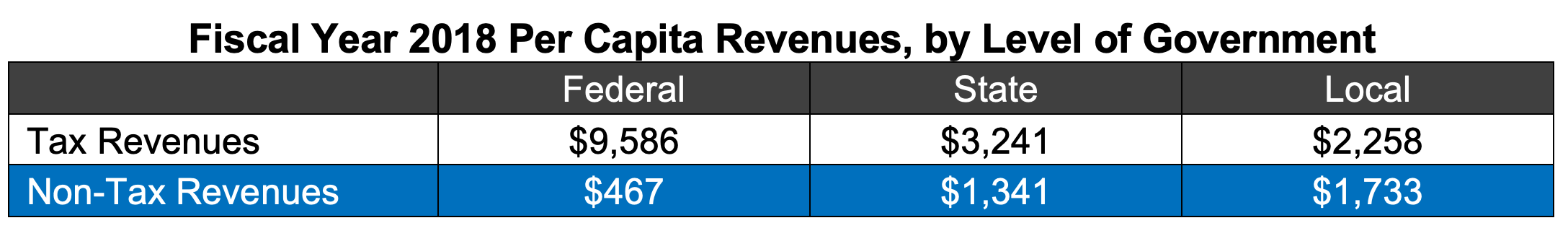

Source: Table created by author based on data from the Office of Management and Budget, the Congressional Budget Office, the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, and the US Census Bureau. Data accessed October 22nd, 2020. Note: Government workers’ contributions to their own retirement and health insurance plans are excluded. Intergovernmental transfers are counted towards the tier of government that originally raised the revenues. All corporate profits taxes are attributed to US residents; if foreigners pay 30 percent of corporate profits taxes, the average American pays $17,497 rather than $18,625.

With these concepts in mind, let’s return to UBI and ask a specific question: Can we afford to add a UBI to existing government programs? In fiscal year 2018—the most recent year for which we have comprehensive federal, state, and local data—the average American paid nearly $15,100 in taxes across all levels of government.1 Even this sum, however, understates the totality of government fiscal policy. Governments also levy various fees and fines—parking fines, bus fees, charges for school meals, etc. When these amounts are included, revenues exceed $18,600 per person, as shown in the table above.

In fiscal year 2018, governments collected nearly 35 percent of the average American’s $54,000 income. Let’s try adding a reasonably-sized UBI to this system. For government to fund an annual UBI of $12,000, it would have to raise the total tax rate from 35 percent to 57 percent. The average American would pay over $30,600 to the government, keeping just $23,300 for himself.

It gets worse. The tax increase would greatly discourage work, but so too would the UBI itself. Just as the higher taxes would create a negative substitution effect, the $12,000 check would create a negative income effect. Because you would receive $12,000 no matter what, you could achieve your desired income while working fewer hours. However, taxes are paid by people who work. Faced with a 57 percent tax rate and a $12,000 cushion, people would work fewer hours, thus eroding the tax base needed to fund a UBI in the first place. By its very nature, UBI cannot be funded out of higher tax revenues. Liberal supporters of UBI are calling for a policy that just won’t work.

Cherry-picked UBI studies don’t generalize

Liberal supporters of UBI occasionally call forth a counterargument: while UBI may discourage work in theory, studies show this doesn’t happen in practice. This is wrong for two reasons. First, as Matt Weidinger of the American Enterprise Institute points out, far more studies run the other way. In other words, UBI supporters cherry-pick their studies. Most UBI trials show negative effects on work, yet advocates only cite the studies which conform to their preexisting beliefs.

Second, even advocates’ preferred studies tell us little about how UBI would work on the national scale. UBI experiments grant small, temporary benefits, and are almost never funded out of tax revenues. “If you know that your UBI payment is going away in 12 months, that’s going to create a different incentive than if it’s permanent,” Weidinger told me.

Even the real-life UBI in Alaska—often lauded by supporters as the prototype for a national policy—grants residents just $1,606 per year, and is funded by revenues from a state-owned oil fund. None of these studies or real-life experiences suggests that a large, permanent UBI can be funded out of tax revenues.

In 2018, Mike Dunleavy won the Alaska Governor’s race by promising to expand the UBI to $6,700 per person. His administration is now backing away from this proposal because they can’t figure out how to pay for it. Some experiments are more telling than others.

The conservative version of UBI

Conservatives see UBI not as a complement to the safety net, but as a substitute for it. They would make room for a UBI by eliminating programs such as Social Security, food stamps, and Medicaid.

This policy would harm the poor by shifting the safety net from targeted benefits towards a universal one. Targeted safety net programs exclusively benefit people in need, whereas universal programs disperse smaller benefits across a wider population. If we had $100 and were in a room with one poor person and nine rich people, a targeted benefit would give all $100 to the poor person; a universal benefit would give everyone $10. “I believe in progressive taxes and means-tested benefits,” said Arthur Brooks, a former president of the conservative American Enterprise Institute. “If you provide the same help to people in need as to those not in need, then you don’t have a real safety net.”

In recent decades, the safety net has shifted more towards targeted benefits through the creation of programs such as Supplemental Security Income (1972), the Earned Income Tax Credit (1975), the Child Tax Credit (1997), and the Affordable Care Act (2010). The results of these changes are striking. In 1967, government policies lifted just five percent of otherwise-poor Americans out of poverty. By 2017, they were pulling 44 percent of this population above the poverty line. The conservative version of UBI would undo this progress overnight, throwing roughly 40 million people back into poverty.

As if that weren’t enough, the conservative UBI would worsen and lengthen most recessions. Safety net programs are what economists call automatic stabilizers—when large numbers of people suddenly lose their jobs or slip into poverty, programs such as unemployment insurance and Medicaid automatically replace their lost incomes and health insurance. Automatic stabilizers help people during periods of extreme need, and they boost the economy by preventing significant drops in demand. If these programs were replaced with a UBI, the government would be unresponsive to Americans’ heightened needs during recessions, and the economy would shed jobs and wealth more quickly.

In June 2016, the University of Chicago polled a large group of conservative, liberal, and apolitical economists on replacing our current safety net with a $13,000 UBI. Twenty-five economists either disagreed or strongly disagreed with the proposal; just one agreed, and zero strongly agreed. “The current safety net balances providing for the poor while limiting the amount to which it discourages earnings and work,” said Mark Shepard, a professor of economics at the Harvard Kennedy School. “If you did the conservative version [of UBI], you would actually be weakening the safety net and creating a massive, regressive transfer.”

Unlike the liberal version of UBI, the conservative version is highly workable. It could be implemented. But let’s hope it isn’t.

Andrew Yang’s UBI proposal

Andrew Yang’s UBI proposal was essentially the liberal version with three modifications. Somewhat miraculously, each of his changes made an already bad policy even worse.

First, Yang’s UBI wasn’t truly universal—it only applied to adults. Under his program, a single mother with five kids would have received the same support as a childless individual. This is completely backwards: the poverty rate for children is higher than for working-age adults and retirees, and investments in poor children reap benefits throughout the child’s life. If anything, there is a much stronger case to be made for a Child Basic Income (CBI) than for an Adult Basic Income (ABI).

Second, Yang mandated that individuals receiving more than $12,000 from the government be exempt from his ABI. Only adults currently receiving no government aid or aid of less than $12,000 would have received the ABI. (For the latter group, the ABI would replace their current benefits.) But since the current safety net targets its benefits to the lowest-income Americans, Yang’s ABI would have done nothing to support the poor. Yet if you are wealthy enough to not require any aid, Andrew Yang was there with a helping hand.

Finally, while Yang promised to raise taxes rather than cut benefits, most of his revenues were supposed to come from higher growth. In a June 2019 interview with Bill Maher, he argued the following:

Maher: How much would that [UBI] cost, in total, for a year in this country?

Yang: Well, the headline cost gets a lot lower than people think because a lot of this money is just going to go back right into the economy. It’s the trickle-up economy—

Maher: Right! Cuz poor people spend it.

Yang: Yes! If I gave you a thousand bucks a month, you might not even notice. But if you put a thousand dollars a month in the average American consumer’s hands, it’s going to get spent right in their main street businesses; it’s going to create two million new jobs, because that money is just going to go to tutoring, and car repairs, and the occasional night out, and it’s going to circulate over and over again.

Yang’s comments reflect a profound misunderstanding of how money works. Money is not a store of value, and printing more cash does not make us richer. If people spend a larger pot of dollar bills on the same goods and services that were available beforehand, we will simply pay higher prices. Unless Yang has a plan to boost the production of goods and services, his ABI would simply result in inflation.

Yang never grappled with the idea that his ABI would disincentivize work. In the FAQ section of his campaign website under the heading “Won’t people stop working?” Yang’s campaign wrote the following:

Decades of research on cash transfer programs have found that the only people who work fewer hours when given direct cash transfers are new mothers and kids in school. In several studies, high school graduation rates rose. In some cases, people even work more. Quoting a Harvard and MIT study, “we find no effects of [cash] transfers on work behavior.”

In our plan, each adult would receive only $12,000 a year. This is barely enough to live on in many places and certainly not enough to afford much in the way of experiences or advancement. To get ahead meaningfully, people will still need to get out there and work. [emphasis and brackets in original]

There are two problems with this passage. First, the quote is inaccurate; it never appears in the cited article. The sentence which the campaign appears to have modified points to a lack of negative findings rather than the existence of positive ones: “Aggregating evidence from randomized evaluations of seven government cash transfer programs, we find no systematic evidence of an impact of transfers on work behavior, either for men or women.”

Second, and more importantly, the Harvard-MIT study lends no support to UBI. In fact, the article is about precisely the opposite policy—targeted cash benefits. Granted, academic writing can be a slog. Academics often bury their main points, and most people skim such articles rather than giving them a full read. But how far into the article do you have to read before realizing that it’s about targeted benefits? One word. The first sentence reads: “Targeted transfer programs for poor citizens have become increasingly common in the developing world.”

One of the Yang campaign slogans was MATH—an acronym for Make America Think Harder. It’s a nice slogan, and in Yang’s case, a great aspiration.

UBI in exceptional circumstances

The entire preceding analysis assumes a normal economy. But could UBI work in exceptional circumstances? Yes. The first instance in which a UBI could prove helpful is as a temporary measure during recessions. The best stimulus measures are timely, targeted, and temporary. A UBI will always score poorly on the second criterion, but since sending out checks is administratively simple, UBIs can be disbursed quickly. So long as they do not become a permanent feature of government policy, UBIs can be administered at the beginning of recessions, before being replaced by better-targeted measures as the crises wear on. (The coronavirus checks from earlier this summer aren’t really UBIs, since adults earning more than $99,000 were exempt.)

The second instance would be during a job-stealing robot apocalypse. There is no guarantee that such an apocalypse is coming, but if it does, a UBI-like proposal would make sense. Given that the American economy employed about 159 million people as of the end of last year, job losses will have to be widespread to justify shifting from targeted benefits to universal ones. If virtually no one has a job, a UBI would look similar to targeted benefits for the jobless anyway. But in today’s economy, to successfully pitch a permanent UBI, advocates will have to answer two questions. First, how are they going to pay for it? Second, why should the benefits be universal rather than targeted?

In a way, the second question marked a bright dividing line during the 2020 Democratic primary. Some candidates favored UBI, Medicare For All, and free public college, while others pushed for more generous tax credits, a public health insurance option, and expanded Pell Grants. As a supporter of targeted benefits, I found myself nodding my head when one of the candidates said the following about free public college:

If you were to apply resources, you would want to apply resources in ways that don’t necessarily advantage the top third of your population, by educational attainment, exclusively. You would be trying to build more paths for the other two-thirds, which investing in trades and apprenticeships would do. And you would try and provide for the people who are the weakest and the most vulnerable in the job market, which are not going to be the people that are attending college.

On that issue, at least, I agree with Andrew Yang.

Reference:

1 Data on state and local revenues are from the 2018 State & Local Government Finance Historical Datasets and Tables at the US Census Bureau. Data on federal revenues are from the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Historical Table 2.1, OMB Historical Table 2.5, and the OMB Supplemental Materials Public Budget Database. Data on total personal income are from the Congressional Budget Office’s July 2020 Historical Data and Economic Projections. Resident population estimates are from Table A-1 of the Census Bureau’s State Population Totals and Components of Change: 2010-2019. My estimate of Fiscal Year (FY) 2018 per capita personal income ($53,964) was cross-referenced with the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis’s estimates of per capita personal income for calendar years 2017 ($52,114) and 2018 ($54,601). An accurate estimate for FY 2018 should fall between the 2017 and 2018 calendar year estimates.