Crisis of Faith

Reflections on Solzhenitsyn's Harvard Address

This imbalance between rights and responsibilities is not only restricted to individuals, it is also affecting our governmental, societal, and cultural institutions.

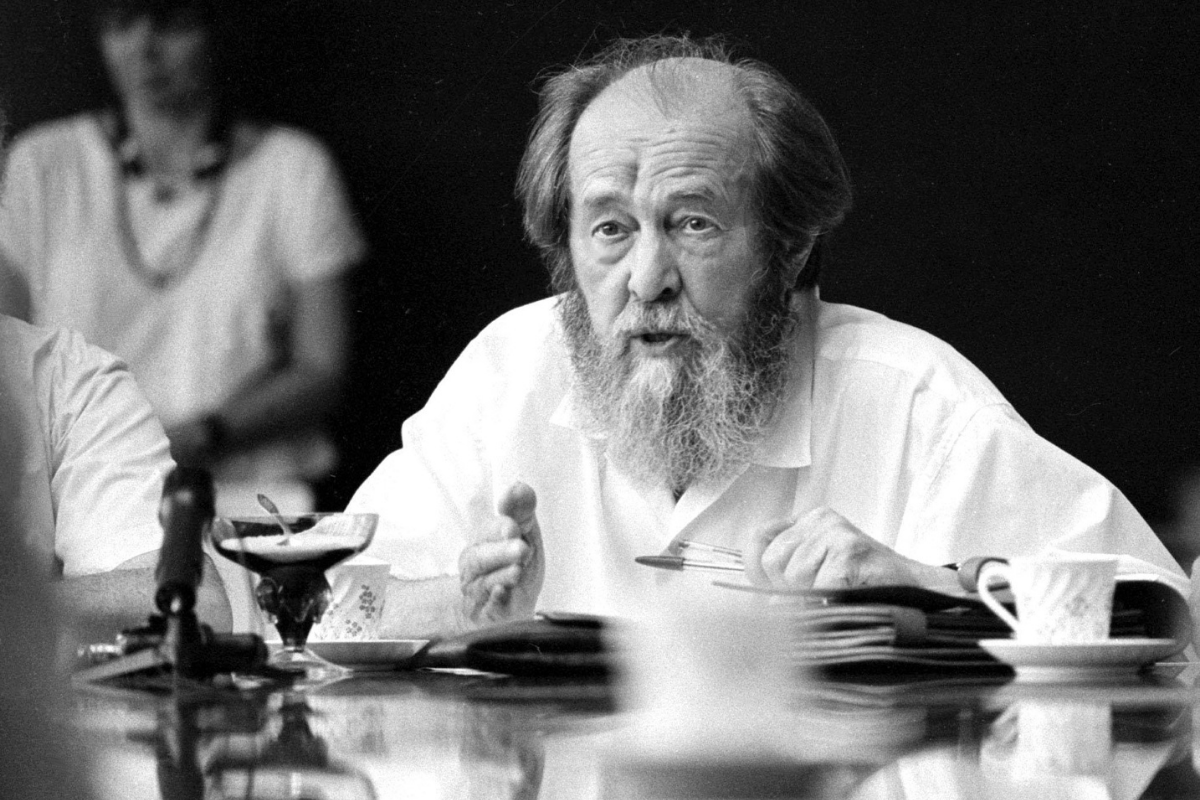

In his 1978 Harvard commencement address, A World Split Apart, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, a fierce enemy of the Soviet system, delivered a forceful and insightful critique of the West, a society which he characterized as spiritually weakened by rampant materialism. The man who, when forced to leave his own country four years earlier, encouraged his countrymen to “live not by lies”, gave us a magnificent lesson in how to not be blinded by our own sense of superiority, and urged us to ask hard questions about who we are and where we are going.

When I first heard this speech in 1978 as a young refugee from communist Romania, I was able to appreciate Solzhenitsyn’s address in terms of the competition raging then between the West and the East, but did not comprehend its larger meaning. Rereading it today, in the fall of the horrible year 2020, I find it truly prophetic. It is now painfully clear that, as Solzhenitsyn was able to discern 42 years ago, the West has been gradually losing the will and intellectual ability to defend itself, not so much against foreign armies as it may have appeared in 1978, but against an army of internal critics determined to demolish everything the West used to stand for.

In the central part of the address Solzhenitsyn said:

A decline in courage may be the most striking feature which an outside observer notices in the West in our days. The Western world has lost its civil courage, both as a whole and separately, in each country, each government, each political party, and, of course, in the United Nations. Such a decline in courage is particularly noticeable among the ruling groups and the intellectual elite, causing an impression of loss of courage by the entire society. Should one point out that from ancient times declining courage has been considered the beginning of the end?

A lot has been written lately about the Woke phenomenon, with excellent accounts of its ideology, genesis, and, though not yet complete, its long march through the institutions.

But I have still found myself at a loss to understand how this simplistic, tribalist, intellectually confused, petty, and terribly divisive ideology appears on the verge of displacing our old, magnificent worldview, anchored in the universal “unalienable Rights endowed by our Creator and secured by the Laws of Nature.”

I wrote this essay in the hope that revisiting what Solzhenitsyn had to say in 1978 may provide a clue to why we find ourselves so vulnerable today. I take from his text two important themes which I believe are relevant for this task. One is the growing imbalance between rights and individual obligations, the second is the loss of faith.

Rights and obligations

In his address, Solzhenitsyn says that Western societies place a strong emphasis on freedom and rights. In the US, in particular, these rights are staunchly defended by the Constitution and implemented by a legalistic process, based on specific rules, which studiously avoids making non-legal moral judgements. At the same time, he observes, there has been a notable decline in individual obligations, or personal responsibility. These values are, of course, nowhere to be found in the Constitution but their importance was taken for granted by its founders. Personal responsibility, they thought, was naturally enshrined in an education steeped in tradition, in individual notions of selflessness, self-restraint, self-reliance, truthfulness, honor, personal sacrifice, etc. It is not that the founders left these virtues out of the Constitution because they considered them dispensable—on the contrary, they were keenly aware of their importance and thought that the type of government they were proposing would be unimaginable in their absence. But they felt that imparting these virtues was best left to the traditions and religious beliefs of the people, a view clearly expressed in the Federalist Papers.

The imbalance between rights and obligations in Western societies is constantly growing as the common understanding of rights is expanding, thus strongly undermining any remaining notions of individual obligations. The Left includes among what it calls “human rights” not only those guaranteed by the Constitution but also the rights to free health care, free education, free child care, the right to unrestricted and free abortions, and makes constant political demands in their name. Recently, one hears voices calling for a guaranteed “Universal Basic Income’’ as another human right. Whatever one thinks about the merits of these new rights, when put into practice through vast bureaucratic programs, they reduce personal responsibility and increase the power of the state. One may also ask whether there is any possible limit to this expansion? In Communist countries everybody had the right to work, guaranteed by the state, viewed as the most fundamental human right. In practice, it meant that everybody who was not penalized by the Party could get a wretched job with little hope for advancement. The state could implement such a policy because it controlled all the means of production. Are we heading in the same direction?

This imbalance between rights and responsibilities is not only restricted to individuals, it is also affecting our governmental, societal, and cultural institutions. In a series of lectures at Princeton University two years ago, Yuval Levin decried how these institutions are neglecting their formative responsibilities in favor of performative actions. He provides a thorough analysis of how congressmen, journalists, judges, and university professors prefer to behave, often to the detriment of the institutions they represent, as independent actors on the larger stage provided by the irrepressible, omnipresent, and vastly irresponsible media. The result is an accelerating lack of trust in the institutions they represent and a decline of social capital, which is essential to the health of the republic.

Collapse of faith

But it is not just that our basic institutions are declining by neglecting their essential responsibilities. Far more worrying is the fact that the liberal ideas underpinning these institutions are themselves collapsing under a constant barrage of criticism. In other words, people are losing faith in our foundational liberal values. This fact, barely visible in 1978, is an essential part of the present reality of Wokeness. Examples abound, but I will confine myself to one of the most outrageous. According to a recent graphic display at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, visitors were told that individualism, hard work, stable families, logical thinking, and scientific objectivity are characteristic of “white” people. It follows, by that logic, that any attempt to assert these as universally desirable virtues must be viewed as racist. Needless to say, in the postmodern world of the Woke, logic itself is a social construct to be used only when it advances the political objectives of the movement.

To understand the scope and intensity of this collapse it helps to summarize the origins of this phenomenon.

Marxism has from its inception been very good at detecting and criticizing some of the more obvious deficiencies of capitalism—yet, as we know, terrible at offering any workable solutions.

Marxists were obsessed with taking power, and whenever they did, by insurrection or conquest, their rule descended rapidly into some awful form of totalitarianism. But with the exception of the underdeveloped Russia, and later China, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Cuba, capitalism turned out to be more enduring than the original Marxists envisioned, partly because of its remarkable ability to adapt and reform itself within the cultural traditions and democratic institutions that sit alongside it. That led to a new form of criticism, cultural Marxism, initiated by Gramsci, directed at the “hegemonic culture” through which capitalism maintains its power. The intense focus on criticizing all aspects of Western societies with the ultimate aim of weakening and eventually destroying them was continued by the Frankfurt School, under the name of Critical Theory, and brought to the US where it found a niche in American colleges and universities and from where it soon started its long march through America’s institutions.

Today, various critical theories dominate entire academic departments, such as Gender Studies, African American Studies, Ethnic Studies, Sociology, Education, etc., and provide a growing influence in almost all academic disciplines except maybe STEM—though almost certainly not for long. Take any possible identity group and you can find a critical theory dedicated to it. Critical race theory (CRT), for example, analyzes society from the point of view of race, while critical feminism theory is focused on understanding gender inequalities. Critical pedagogy theory (CPT) criticizes the traditional relationship between teacher and student which, apparently, is like the relationship between a colonizer and the colonized. These theories provide road maps for liberation from the oppressive, dominant power structures. They are also connected to each other by the doctrine of intersectionality, which claims to understand how a person’s various identities (from gender, sex, race, class, to disability, physical appearance, height, weight, etc.) combine to create unique modes of discrimination or privilege. Add to this a contempt for capitalism, an apocalyptic vision of climate change, and the neat trick of combining moral relativism in theory with a large dose of moral absolutism in practice, and you get the main contours of the so-called Woke phenomenon.

According to Yoram Hazony, in a recent article in Quillette, the Enlightenment principles of freedom and equality are too abstract when not supported by other traditions to provide an effective defense against systematic Marxist criticism. Here is how he described the “dance between liberals and Marxists”:

Enlightenment liberals observe that inherited traditions are always flawed or unjust in certain ways, and for this reason they feel justified in setting inherited tradition aside and appealing directly to abstract principles such as freedom and equality.

Liberals declare that henceforth all will be free and equal, emphasizing that reason (not tradition) will determine the content of each individual’s rights.

Marxists, exercising reason, point to many genuine instances of unfreedom and inequality in society, decrying them as oppression and demanding new rights.

Liberals, embarrassed by the presence of unfreedom and inequality after having declared that all would be free and equal, adopt some of the Marxists’ demands for new rights. The dance then continues by iterations, with never-ending new demands by the Marxists.

In a similar vein, Solzhenitsyn asks, prophetically, how could the West “with such splendid historical values” in its past lose the will to defend itself. He goes on to say:

How has this unfavorable relation of forces come about? How did the West decline from its triumphal march to its present sickness? Have there been fatal turns and losses of direction in its development? It does not seem so. The West kept advancing socially in accordance with its proclaimed intentions, with the help of brilliant technological progress. And all of a sudden it found itself in its present state of weakness.

Solzhenitsyn concludes that “the mistake must be at the root, at the very basis of human thinking in the past centuries.” He refers to “the prevailing Western view of the world which was first born during the Renaissance and found its political expression from the period of the Enlightenment. It became the basis for government and social science and could be defined as rationalistic humanism or humanistic autonomy. It could also be called anthropocentricity, with man seen as the center of everything that exists.”

He also observes,

In early democracies, as in the American democracy at the time of its birth, all individual human rights were granted because man is God’s creature. That is, freedom was given to the individual conditionally, in the assumption of his constant religious responsibility.

Faith in God has been gradually displaced by a Faith in Man as a materialistic entity.

Solzhenitsyn again:

The West ended up by truly enforcing human rights, sometimes even excessively, but man’s sense of responsibility to God and society grew dimmer and dimmer.

Solzhenitsyn points out that humanism, divorced from its religious roots, is no match for the current materialism of the Left. In the same spirit as Hazony, he observes:

Liberalism was inevitably displaced by radicalism; radicalism had to surrender to socialism; and socialism could never resist communism.

He also says something we refugees from the East know all too well. It is this same kind of support from intellectual elites today that has allowed the Woke phenomenon to spread:

The communist regime in the East could stand and grow due to the enthusiastic support from an enormous number of Western intellectuals who felt a kinship and refused to see communism’s crimes.

Personal comments

I would like to end with a few personal comments inspired by Solzhenitsyn’s text.

It is a tragic fact of the human condition that important human aspirations and needs such as freedom, justice, equality, personal security, spirituality, and self-expression are, if not exactly in contradiction with each other, in a state of perpetual conflict. Extreme levels of personal insecurity are intolerable—people will accept infringements of all their other aspirations if they feel their lives are endangered. Unfettered personal freedom, on the other hand, may lead to terminal anarchy if it is not accompanied by a legal system designed to protect justice—that is, the rights of all. Radical equality, as envisioned by Marxism and presently by the Woke ideology, is at odds with human nature; it is thus incompatible with both freedom and justice and can only be imposed by force. It is no accident that both private property and bourgeois style families, the greatest sources of inequality in any society, but also great guarantors of individual freedoms, were proscribed by Marx in the Communist Manifesto.

Spiritual aspirations, manifested through organized religion, can also lead to cancellations of freedoms and terrible conflicts. The absence of religion, however, may be even more problematic, as people tend to fill the vacuum created by the disappearance of old religions with new ones, which are often more fanatical and are not constrained by fidelity to ancient, inspiring texts or anchored in tradition. Many observers have pointed out that the Woke phenomenon represents a new, postmodern religion.

Superimposed over this state of conflict is yet another one based on the way people make choices; that is, based on reason, faith, or the sheer assertion of power. Reason and faith are often viewed as polar opposites, and we divide the main eras of Western history into the age of faith, before the Renaissance, and that of reason or the Enlightenment. But can they be so neatly divided? In the absence of reason, faith may lead us astray, but reason without faith seems often to run in circles, sterile and incapable of making choices. People think that science or mathematics are completely based on reason, but this is just wrong. A mathematical theorem is indeed presented as a long sequence of logical arguments but that is not the way mathematicians arrive at their truth. Every new, deep theorem starts with a leap of faith, followed by reasoned arguments and not the other way around. Science is not that different. Kepler, of a strong mystical inclination, was obsessed with his belief that the observable physical world must be explainable by mathematics and so were Copernicus, Galileo, Leibnitz, and Newton. God for them talked through numbers and equations. Einstein was all his life driven by a vision of a unified theory that combined all known forces. Faith in this vision continues to be the driving force in theoretical physics. It is faith that gives purpose and direction, and reason that keeps faith in check. It is telling to note in this sense that the philosophical conceit of modern rationalist thinkers, starting with Descartes, that truth ought to be discoverable by reason alone, has led instead to the opposite conclusion embodied in the radical relativism of postmodern thinkers such as Foucault and Derrida. Note also that faith has a role to play in any human endeavor, good or bad, while reason is often absent

I believe that the extraordinary past successes of Western civilization were due to a very fortunate, naturally evolving, often imperfect, at times broken, balance between the human aspirations enumerated above, facilitated by a precarious equilibrium between reason and faith. Such a fortunate balance was manifest in the democratic systems of governments the West painfully arrived at.

As noted by Solzhenitsyn, various factors, including the new rights, pushed by the Left in the name of expanded notions of personal security, material well-being and equality have reduced the need for self-reliance and altered the balance between freedoms and responsibilities. That process, enhanced by the constant drumbeat of Marxist and Neo-Marxist criticism of cultural values and mores, parroted by the media, Hollywood, etc., led to a manifest depletion of human capital and the collapse of faith. Not just faith in God, as Solzhenitsyn writes, but also faith in our common destiny as Americans.

The Woke movement is taking advantage of the present confusion by trying to impose another version of radical equality, based on the myriad of group identities they can fathom. Their project is obviously self-contradictory and dangerous, yet our leaders seem either determined to go along with it or too cowardly to resist. Many well-intentioned people, especially the young, are confused by an uneasy sense of guilt. This feeling is only exacerbated by a postmodern historical narrative obsessed with finding grievances to the detriment of a measured understanding of the past. The process of deterioration has been going on for a long time but appears now to be moving much faster.

So the question I pose to all of you today is this: Can the process we are witnessing be reversed? Can the old balance be restored? How? Solzhenitsyn himself does not seem to believe that restoration is possible but points instead to some kind of mystical resurrection. Here is how he ends his address:

If the world has not come to its end, it has approached a major turn in history, equal in importance to the turn from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance. It will exact from us a spiritual upsurge: We shall have to rise to a new height of vision, to a new level of life where our physical nature will not be cursed as in the Middle Ages, but, even more importantly, our spiritual being will not be trampled upon as in the modern era.