Middle East

The End of the Islamic Republic of Iran?

The regime is a victim of its own fanaticism, corruption, and incompetence.

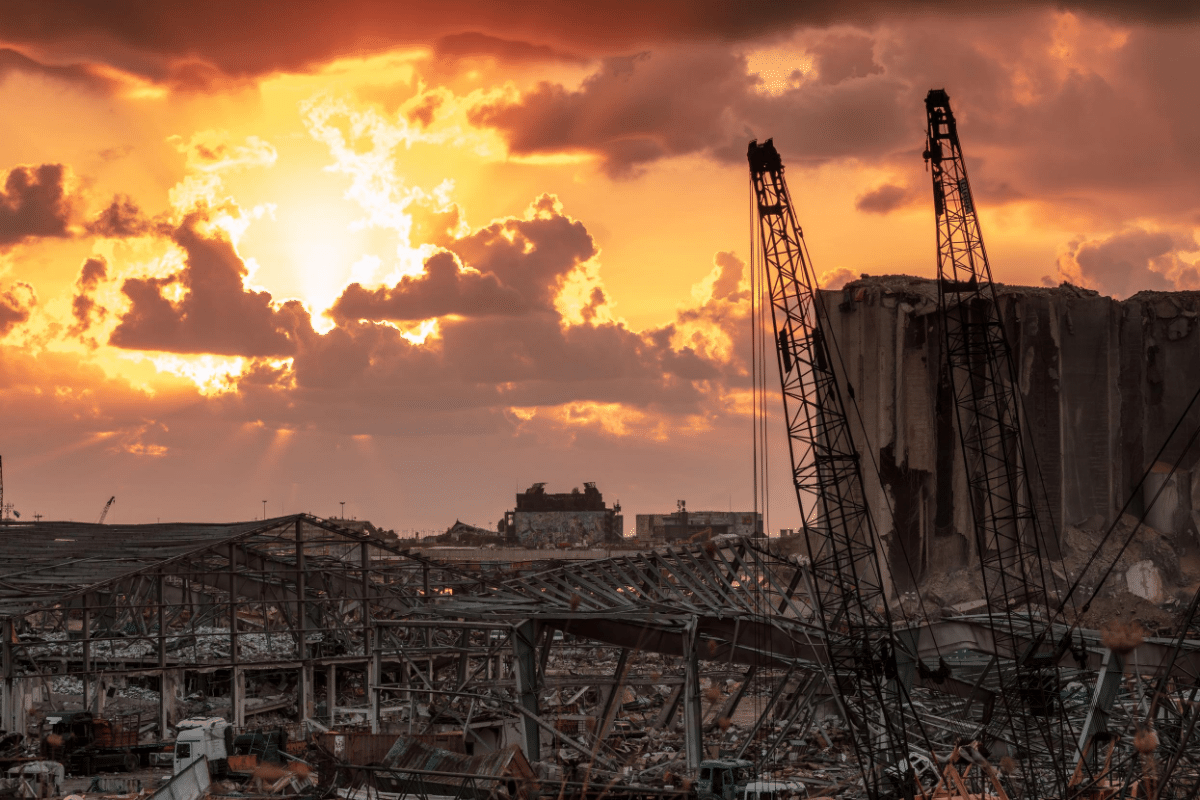

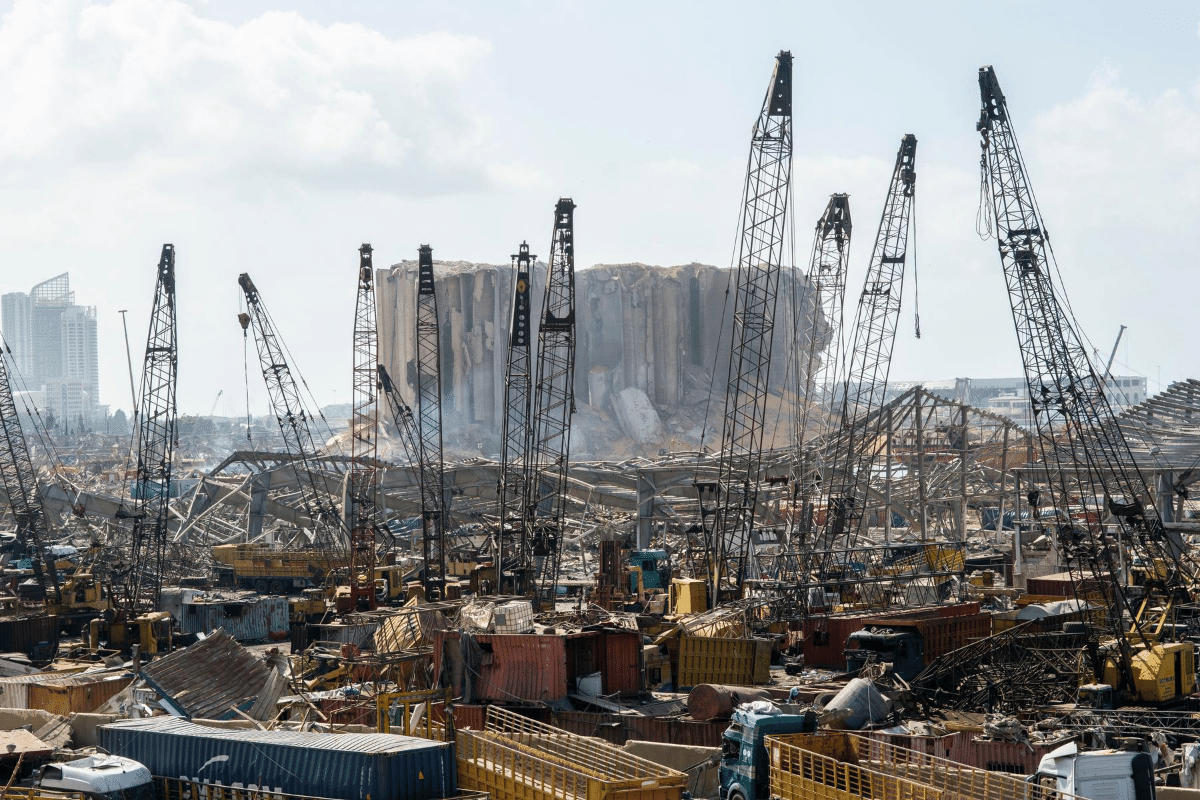

The recent explosion in Beirut was like the most recent episode in a tragic decline. Beirut used to be known as Paris in the Levant and the bride of Middle Eastern cities. It was once beautiful, cultured, and exotic. No longer. Last year, hyperinflation, shortages of food and energy, unaccountable government, and a steady erosion of social liberties combined to ignite widespread protests. The protestors only demand: That Iran get out of their country. A New York Times investigative team found that the explosion had been the result of negligence—a rot inside the government.

Those protests coincided with protests in Iraq, which also demanded an end to Iran interference, and in Iran itself, where protestors demanded that Iran stop meddling in Lebanon and Iraq. In neighboring Syria, half a million died between 2011 and 2016, and millions more were displaced. There are signs of life in Syria, but no sign of living. Everything Iran touches dies, and its regime extends its malign influence wherever it can. The civil war devastating Yemen began when the Iran-backed Houthis overthrew the Yemeni government in 2011. The Gaza Strip has been a totalitarian quasi-state since the terrorist organization Hamas seized the territory, which it continues to misgovern with financial and military aid provided by Iran.

In Iraq, Iran’s influence began in the mid-2000s during the American-led war to topple Saddam Hussein. That war produced two problems: An insurgency and a sectarian civil war, and Iran was happy to inflame both by supporting Shi’ite militias as they murdered Iraqi Sunnis and American peacekeepers. In 2011, the United States was negotiating an extension to its military presence in Iraq in order to protect the fragile democracy there. Qasem Soleimani, the leader of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps’ notorious Quds Force, summoned Iraqi politicians and demanded that they reject US requests: The Americans will leave you one day, he told them, but we will always remain your neighbors. The Americans failed to reach an extension agreement and when they eventually left, Iranian influence inside Iraq only grew. The Iraqi democracy, for which the United States and its allies had sacrificed so much, continued to erode until anti-Iran protests erupted last year.

In Lebanon, the situation is even more distressing. Following the 1975–90 civil war, Lebanon became a flawed and frail democracy, but a democracy, nonetheless. Shi’ites, Sunnis, and Christians make up most of the country’s population, but Hezbollah, a Shi’ite sectarian militia backed by Iran, now operates as a state within a state, or, rather, the Lebanese state is now an arm of Hezbollah. When the Syrian civil war broke out in 2011, Iranian support for Hezbollah grew, and at Tehran’s instruction, the group threw its support behind the genocidal regime of Bashar al-Assad. Heavily armed, richly funded, and now battle-hardened, Hezbollah’s grip on Lebanese politics tightened through bribery and armed intimidation. By the mid-2010s, there was almost nothing left of the Lebanese democratic experiment, as corruption led to a precipitous decline in standards of living.

All over the Middle East, wherever one sees bloody mayhem, one invariably finds Iran’s footprints. Iran has no interest in being a positive agent in the region or beyond, and it is time for American policymakers to come to terms with this fact. Iran is funding radical mosques in Latin America, while Hezbollah is operating in Mexico and elsewhere. In South Asia, Iran has been developing an Afghan version of Hezbollah, called the Fatemiyoun Brigade. The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), Iran’s powerful paramilitary group, is developing a naval base in the Indian Ocean. Meanwhile, Iran is empowering America’s great power adversaries. Most worrisome is the forthcoming agreement to lend China an island in the Persian Gulf for a military base. Russia, too, has been a beneficiary of warm relations with Iran, and the two countries cooperated to thwart US attempts to facilitate a transition of power in Syria.

The Islamic Republic of Iran is a revolutionary and ideological state. Part of this ideology, from which the state derives legitimacy, is Shi’ite imperialism, anti-Americanism, and anti-Zionism. In fact, the IRGC’s mission statement mentions that it is the corps’ goal to export the 1979 Islamic revolution. To expect the Islamic Republic to behave as a normal state is to expect it to stop being itself. As Dartmouth Professor Misagh Parsa has written in his book, Democracy in Iran, reform in Iran is not a reasonable objective, it is a fool’s errand. Four decades of engagement and attempts to engage Iran have failed to modify the regime’s behavior. Even the Iran nuclear deal only fueled Iran’s conventional aggressions in the region.

The good news is that the desire to see the back of the Islamic regime has never been stronger inside Iran, and outside it, Arab states are aligning co-operatively with Israel against the regional Iranian threat. Before the pandemic, protests were more common in Iran than ever, and the regime’s mishandling of the COVID-19 crisis has made it even more unpopular. An IRGC intelligence officer who defected reports that the regime’s popularity is in single digits among Iranians, which—if true—points to a complete collapse in its popular legitimacy even among its traditional base. Demographics are working against the regime, as well. Declining birth rates indicate a concomitant decline in religion, which is bad news for a theocracy.

Furthermore, the Persian Shi’ite population is in relative decline. Credible statistics are scarce, but even official reports (which are almost certainly exaggerated) suggest that Persians constitute only 60 percent of the population, and the vast majority of minorities have historical grievances against the regime. A recent poll has found that 73 percent of the society object to compulsory hijab, a core value of the regime, while 58 percent personally do not want to observe hijab. 37 percent drink alcohol, despite the legal prohibition, and an additional eight percent do not drink because of a lack of access and not due to any religious objection or medical restriction. To make matters worse for the regime, 68 percent believe that religion should not be a source of legislation, even if religious factions are democratically elected, and only 32 percent identify as Shi’ite Muslims.

The regime is a victim of its own fanaticism, corruption, and incompetence. The failure of the reform movement in the 1990s and 2000s has convinced Iranians that the regime is incapable of change. After eight years of domestic and foreign policy mismanagement under Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, it was hoped that the presidency of Hassan Rouhani would bring some pragmatism to governance. In 2015, Iran signed a nuclear deal with the United States and its partners that released frozen Iranian assets worth a quarter of the country’s GDP. Campaigning on this success, Rouhani was re-elected in a landslide. Just months after his second inauguration and before the re-imposition of US sanctions, however, hyperinflation and depression plunged the country back into economic crisis, and sparked unprecedented anti-regime protests.

Iranians have now realized that the problem is not the sanctions or Israel or America or its own “hardliners” but the Islamic regime in its entirety. The beneficiary of the regime’s unpopularity, on the other hand, has been the Israeli government. As I have reported elsewhere, Iranians are developing a more positive attitude towards Israel, and especially towards Prime Minister Netanyahu. Even during the spring and summer explosions inside Iran, which were almost certainly carried out by Israeli agents, Iranians did not rally around their flag, and some even celebrated the attacks on social media and thanked the United States and Israel.

The Islamic Republic has been the source of much evil in the Middle East. But for the first time in its history, it finds itself opposed by a coalition of the United States, Israel, the Arab countries, and its own people. By supporting democratic actors and anti-regime elements, this alliance can force the Islamic Republic to direct its resources to domestic security and in effect self-contain, while the bloc of anti-regime states provides external containment. Beset by internal unrest and economic strife, overextended in its costly foreign entanglements, and facing unprecedented unity from its external foes, the Islamic Republic has never looked more vulnerable. An end to the Revolutionary theocracy and the misery it has inflicted on its own people and the region since 1979 may finally be in sight.