Top Stories

Will Workers' Wages Ever Go Up Again?

With the threat of plant closures hanging over negotiations like the sword of Damocles, union priorities have shifted from bargaining for wage increases to bargaining for job and pension security.

Self-employment, temporary employment, on-call work, home-based work, and telecommuting are becoming more common. In some countries, such as Australia, nearly half of the workforce falls into one of these categories.

The growth in these types of employment opportunities is often attributed to the rise in app-based gig employers like Uber or Lyft. The employment contract signed by those working in the gig economy is very different from what workers in goods-producing industries had come to expect during most of the postwar era. Back then, for example, you knew when you were working. There were regularly defined work hours (normally 40 hours a week, assigned at a fixed time). These days, your gig employer practises just-in-time labour, putting you on perpetual standby. The company will call you when they need you, thanks. And they might need you for only 10 to 15 hours in a week.

And don’t count on receiving much in the way of the non-wage benefits unions negotiated for most industrial workers in America. Get sick or need dental work as a part-time employee in the gig economy? Sorry, companies don’t pay health-care benefits to part-time workers or “independent contractors,” as gig workers are classified by so many of their employers. Vacation pay? Let one of your other part-time employers cover that. And as for a pension? That’s something your government should provide.

Uber and Lyft have both been hit with numerous lawsuits over the legal status of their drivers, but they claim that the independent-contractor status of their workers is essential to the viability of their business model. The state of California has recently passed legislation that requires these companies to treat their so-called independent contractors as actual workers. Labour groups are pushing for similar legislation in other states. It’s debatable just how robust that business model is, however, since neither Uber nor Lyft, despite the billions they’ve raised from investors, has made a profit. Nevertheless, it’s certainly worked out for those in the C-suite. Uber’s five top executives pocketed $143 million between them last year. And their former CEO, Travis Kalanick, became an instant billionaire when the ridesharing company made its debut on the New York Stock Exchange.

As their businesses have grown, these companies have adjusted their payment algorithms in ways that have left less money in drivers’ pockets. The Economic Policy Institute calculated that Uber drivers earn, on average, an hourly wage of $9.21 after deducting expenses such as fees and commissions. In most of Uber’s major markets, that’s below the statutory minimum-wage rate; but since the drivers are classified as independent contractors, they are not covered by minimum-wage requirements. And since the average Uber driver doesn’t last for more than three months on the job, how they feel about their paycheque is a non-issue; they are totally expendable.

With more and more employment contracts following this model, it’s not hard to understand why we haven’t seen much wage growth in the service sector over the past few decades—and why an ever-greater reliance on the booming gig economy points to even weaker wage gains from the sector in the future.

This is especially bad news for millennials—now the largest segment of the labour force, and the cohort most likely to work in the gig economy. Roughly half have a second job to make ends meet. They are the most college-educated generation in history, raised by parents who were convinced that higher education was a pathway to success. But all that education hasn’t translated into higher wages.

The average salary of American millennials is disproportionately lower than the national average. They are doing a lot worse than most of their parents did at the same age—earning about 20 percent less—and their college education has left them with a record $29,000 in student loan debt on average, which costs $351 per month to repay. In Canada, according to the OECD, only 59 percent of millennials had attained the minimum salary threshold for middle-class status, defined as $29,432 (or 75 percent of the median national income). Sixty-seven percent of their parents had reached the middle class by the same age. In other words, millennials are falling behind, even though they’re working harder than their parents did.

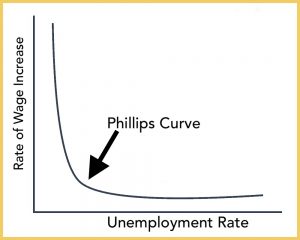

What’s happening to millennials, and indeed all workers, is not supposed to be happening, according to economic theory—and not because it seems unfair. Economic theory has nothing to say about fairness, but it has plenty to say about the relationship of wages to unemployment rates. And what it says is that something is wrong. Stagnant wage growth in the face of low unemployment is an anomaly; it flies in the face of what economists used to refer to as the Phillips curve, which is part of standard macroeconomic theory. On one axis is the unemployment rate; on the other is the rate of wage increases. The higher the unemployment rate, the lower the rate of wage increases. The lower the unemployment rate, the higher the rate of wage increases.

What the Phillips curve tells us is that during economic good times, employers are more willing to pay higher wages to hire additional labour. Why? Because profits are higher, and strikes become more costly when business is booming. But when sales slump during an economic slowdown or a recession, businesses don’t need to hire as much labour and are less likely to grant large wage increases to attract it. For their part, workers are less likely to demand them, knowing that they’re lucky to have a job.

So, with unemployment rates at or near record lows (at least before the pandemic), why didn’t workers strike to demand larger wage increases in the way they’ve done in the past? If you want the answer to this question, head down to your local union hall and ask some of the angry old men hanging out there. Their tale pretty well explains why the Phillips curve is no longer working in today’s labour market.

For the most part, the angry men are blue-collar workers who used to have well-paying jobs in industries like autos or steel, and belonged to unions like the United Automobile Workers (UAW) or the United Steelworkers. In the old days, they would have voted Democrat (if they were American), but the leadership of the Democratic Party since the Clinton presidency has abandoned them in favour of global trade treaties that rendered them expendable. Until Donald Trump came along and courted them, many had stopped voting altogether.

They had good reason. To them, it didn’t matter if Congress was Democratic or Republican, or who was sitting in the White House. Nobody cared about them or their concerns. When it came to the new trade agreements being negotiated, they were the first to lose their jobs, and they would be the last to be rehired, if such a thing ever came to pass.

What made them a primary target of the new trade deals? Those union-won wages and benefits. That was, after all, the whole idea behind organizing a union in your plant—union action got workers higher wages and better benefits. Unions set the market price for labour by forcing companies to bid as high as they could pay.

But globalization changed the rules. Now companies could buy labour wherever they wanted, and what was once a virtue for workers suddenly turned into a vice. Once trade barriers fell, unionized plants were the first to be shut down in favour of the new global supply chains that were being forged with cheap labour markets all around the world. Job losses in unionized plants have been double those in non-union (and generally lower-paying) shops.

It shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone that as union membership shrank, so too did workers’ wages. The right to collective bargaining, which in the past covered as many as a third of all private-sector workers in the US economy, now plays a marginal role in the labour market. You can also credit right-to-work legislation—enacted in 28 US states as of 2019—that enables workers in unionized plants to opt out of paying union dues, hence undercutting a union’s ability to finance itself. Take unions out of most workplaces, and you get a different dynamic than in bygone days: The firm sets the wage, and you can either accept it or not work there.

Union membership hasn’t just fallen markedly in the United States. As a percentage of the labour force, it has declined across OECD countries, even in those that traditionally had the highest rates of unionization. And it’s not just “angry old men” who have lost their union jobs to cheap overseas labour; women are affected, too. Still, the job losses for male union workers have been far more severe than for their female counterparts.

The reason is largely sectoral. Male union members have tended to work in goods-producing industries, like manufacturing, that have been on the front lines when it comes to the invasion of cheap imports from low-wage countries. For example, three-quarters of US manufacturing jobs are held by men. Female union membership is heavily concentrated in the health and education sectors, much of it in the public sector, where, in sharp contrast to the goods sector, employment is still growing and union membership is still relatively strong. It’s harder to offshore a teacher or a nurse than it is a welder.

Elsewhere, the story of declining union membership is much the same. Union membership as a percentage of the labour force in the once highly organized United Kingdom has fallen by about a third. More or less the same reduction has been seen in Germany. In Canada, union membership as a percentage of the labour force has declined by about a quarter. But nowhere in the OECD has union membership fallen more than in the United States, where less than 10 percent of the labour force now belongs to a union.

But even that economy-wide number, which includes government workers, understates the true extent of the decline in union membership in the private sector. During the 1950s, at the zenith of the labour movement, one in every three American workers in the private sector belonged to a trade union. Today, just one in 20 private-sector workers still does.

That precipitous decline has had widespread implications. Unions didn’t just raise wages and benefits for their own membership; they also had a big influence on raising wages for unorganized workers who were employed in highly unionized industries or regions. That was particularly true for manufacturing industries operating in the highly unionized north-east and mid-west parts of the United States.

Back in the day, if you didn’t want your workers to organize a union, the best way of keeping one out was to closely monitor collective-bargaining agreements and, if need be, match union rates. So, when 50 percent of truckers belonged to a union like the Teamsters, their settlements had a big impact on what the unorganized 50 percent were getting paid. But today, when less than 10 percent of truckers are unionized, the other 90 percent can’t expect to get much of a pay lift from their wage settlements.

All of this explains why you rarely hear about workers going on strike anymore, no matter how tight labour markets appear to be. You can’t go on strike for a pay raise if you don’t belong to a union—and even if you’re one of the few workers who still belong to one, your union’s bargaining tactics today are very different from what we used to see in the past.

With the threat of plant closures hanging over negotiations like the sword of Damocles, union priorities have shifted from bargaining for wage increases to bargaining for job and pension security. Strikes have become virtually suicidal. What invariably happens on the rare occasions they do occur is that a fleet of trucks rolls into a plant after midnight on a giant repo operation to cart away all the machinery they can remove before padlocking the factory gates. And the next thing you know, the firm has opened a new plant in Mexico and has sold the factory to some developer who’s going to build luxury condominiums.

That, in a nutshell, is why the Phillips curve no longer works.

Excerpted from The Expendables: How the Middle Class Got Screwed By Globalization by Jeff Rubin. Copyright ©2020 Jeff Rubin. Published by Random House Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.