Art

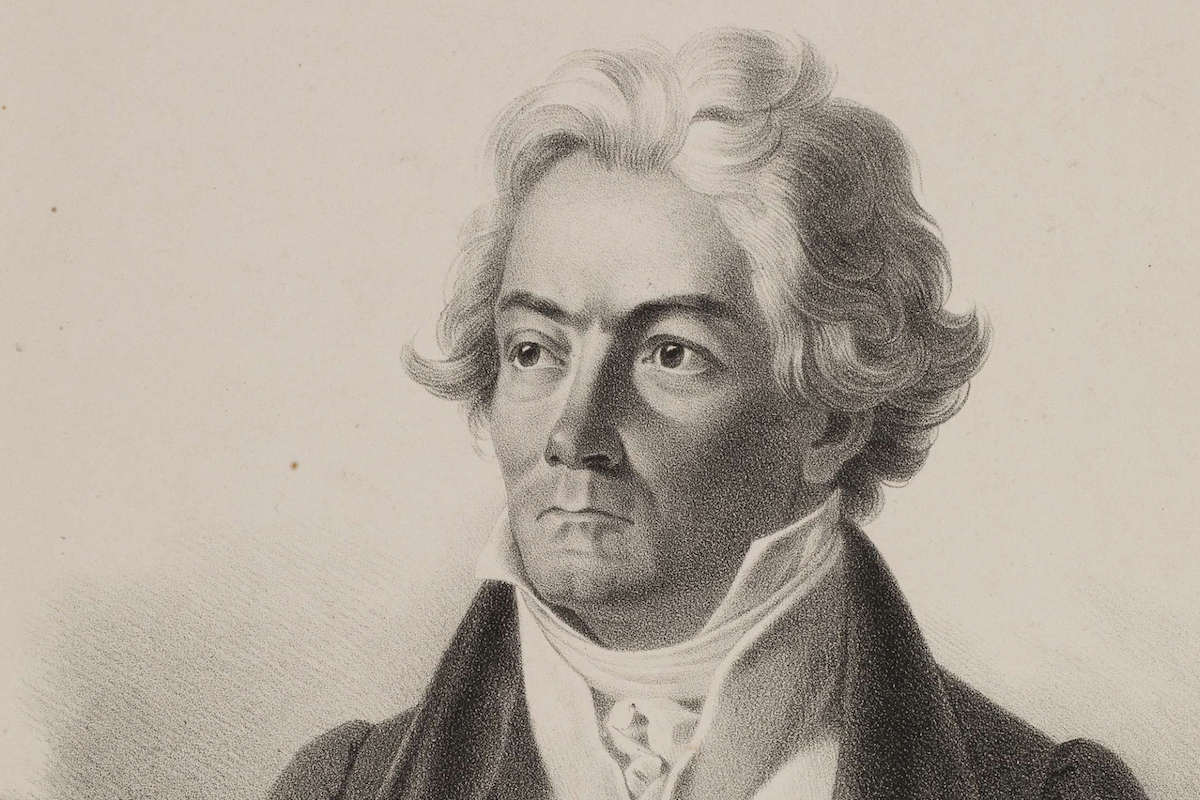

Then They Came for Beethoven

Beethoven is a truly odd target for progressive critics, because his views on geopolitics are known to have been, by the highly regressive standards of his time, quite progressive.

This week, Vox published an article titled “How Beethoven’s 5th Symphony put the classism in classical music.” “Since its 1808 premiere, audiences have interpreted [its opening progression] as a metaphor for Beethoven’s personal resilience in the face of his oncoming deafness,” write Nate Sloan and Charlie Harding. But “for some in other groups—women, LGBTQ+ people, people of color—Beethoven’s symphony may be predominantly a reminder of classical music’s history of exclusion and elitism.” In the article, and an accompanying podcast, the two men ask “how Beethoven’s symphony was transformed from a symbol of triumph and freedom into a symbol of exclusion, elitism, and gatekeeping.”

The article has been widely mocked on social media—in part because the authors (both white men, from what I can tell) offer no real evidence for their claim. That’s odd given that they are purporting to redefine the cultural meaning of what is arguably the most well-known, widely performed, and beloved composition known to humankind. Hundreds of millions of people have fallen in love with this symphony over the past two centuries—many of them inspired by the fact that Beethoven managed to create it while he was succumbing to deafness.

The writers begin their podcast by honing in on the symphony’s first movement—and its inclusion on the famous 1977 Voyager record that was put into outer space, in the hopes of transmitting the human legacy to some other alien civilization. (Other tracks on that recording included percussion music from Senegal, choral music from Georgia, a Night Chant by Navajo Indians, a Peruvian wedding song, selections from Louis Armstrong, Stravinsky, and much more.) In regard to Beethoven, one of the hosts asks rhetorically: “When an alien civilization discovers this golden record and we greet them with, like, dun dun dun DUNNNN… are we the conquering intergalactic empire? Is that what they’re going to think?”

To which the other responds: “It’s a great question, because not everyone feels that Beethoven is the best representation of our species’ collective achievement. For a lot of people, Beethoven’s 5th Symphony doesn’t represent triumph and resilience, but elitism and exclusion.”

I’m a professional cellist who—in non-pandemic times—performs classical music for people of all races. Beethoven’s music is precious to me. And it’s bizarre to hear these two men talk this way. None of what they say bears any connection to Beethoven’s actual work. And their call-and-response faux-curious dialogue about what aliens will think of Beethoven’s supposed “elitism” is embarrassing. Yet Sloan is a musicologist, and Harding is a songwriter.

They do, however, pay a backhanded compliment to Beethoven. This is what happens when a piece of art has such a gigantic influence on a society and its collective identity: The art’s story becomes our story. Naturally, those who demand that our story be rewritten to match a prescribed ideology or theme (such as, say, oppression and intersectionality) will also demand an overhaul in our understanding of the art that defines that story.

The hosts even accuse Beethoven—whose democratic ideals are well-known to anyone who has studied his life story—of empowering colonialism. Says one, “I can almost even see the sort of stride of empire, colonialism, industrialism, all those things that have sort of that same built in narrative of triumph and conquering.”

Really? That’s what you imagine when Beethoven’s 5th begins? I would be scared to imagine what flits though his mind during a performance of Wagner’s Parsifal.

In Japan—which, last time I checked, was populated by quite a few people of color—public performances of Beethoven are a holiday tradition. When asked why so many Japanese people have fallen in love with Beethoven’s 9th Symphony, a Tokyo choral director explained “Beethoven casts a spell on you. Many start off thinking, ‘I can’t do this,’ but then other members urge them to try harder, and working together they get it done. The feeling of accomplishment is sublime.”

That quote appeared in the Japan Times, which, as one might expect, featured a wide array of interviewees to demonstrate the writer’s point. The Vox piece, by contrast, is sourced to the co-authors’ own vague thoughts. To the extent outside authorities are invoked, the attempted smearing of one of history’s great composers is attributed to the “many” (unnamed) people who, we are assured, share the authors’ animus.

I am always happy to praise the universality of Beethoven, and of music more broadly—and never more so than right now, when music is about the only thing we have to fall back on for a sense of collective joy. I have been playing cello since I was five years old, and I remember the first time I played Beethoven’s 5th complete in concert—as a high-school freshman with my youth orchestra in Boston. Since then, I have been fortunate to play it many times, in many parts of the world, to audiences of every skin color. The thrill of the music that I felt that very first rehearsal, up in the woods of Maine at our pre-season retreat—that thrill has never left me. When people ask me if I ever get tired of playing the 5th, I answer—truthfully—that each time I play it, it leaves me more invigorated.

Audiences feel this thrill, too, notwithstanding the suggestion that the enduring popularity of the symphony is owed to snobbish habit. It is one of the few pieces of music that people from all walks of life ask our symphony to play more often. As well as spanning all of the planet’s races, Beethoven’s fans span young and old, and rich and poor. I know this, because I have often given out my complement of free tickets to people who cannot afford to attend but are dying to do so. There is something about the composer, and specifically about this piece, that can cause an audience member to leave the concert hall a different person.

Whenever I think of our capacity to love music—even on first hearing—I remember the time when I was in Qatar, playing with my orchestra. We were rehearsing the overture to Wagner’s Tannhaüser. The orchestra had put a clip of the rehearsal online, and I was watching it that evening when a Filipino hotel worker came to offer turndown service. He didn’t speak English fluently, but we fell into conversation. I pointed at the iPad I was using to play the video, and put on the part of the overture where the brass are playing a huge, soaring theme, and the violins are almost fighting back, playing a thicket of notes, like an uprising against the brass—a thrilling passage. The worker told me he’d never had the chance to hear any classical music in his life, yet found himself in tears by the end of the passage. I don’t know if he ever heard a single note of classical music since our meeting. But where the power of music is concerned, that one brief moment speaks for itself.

Beethoven is a truly odd target for progressive critics, because his views on geopolitics are known to have been, by the highly regressive standards of his time, quite progressive. It would make far more sense to target someone such as Wagner, whose personal defects and despicable views are well-known. And in that Qatari hotel room, I certainly could have held forth with a speech about all this. But what interest would that have served, except stripping the beauty from a fine piece of music?

I really wonder what Sloan and Harding have to say about the Afghan Women’s Orchestra, which in 2017 performed Beethoven’s Ninth at the World Economic Forum. Please watch the brief YouTube clip, which appears below, and ask yourself whether you find yourself inspired—or, channeling Vox’s musical experts, tsk-tsking at all these misguided women paying homage to white supremacy.

Music of this type has no fixed story. It has infinite stories, as the possibilities of fantasy and enchantment are endless. There is no set program, no agenda. And if Beethoven’s 5th makes Sloan and Harding imagine the world’s people of color crushed under western jackboots, perhaps that’s something they might like to work on privately. Don’t blame the music.

When I interviewed Walter Isaacson for the first episode of my recently-launched podcast, I asked him if we needed to do a better job defending the integrity of the humanities. His answer was optimistic: The humanities “naturally defend themselves.” Given Beethoven’s power to inspire, his was the last cultural citadel I expected to see besieged. Yet here we are. Next month, maybe Mozart. Or Bob Dylan. Or Britney Spears. Once we agree to subordinate our love of art to the dictates of joyless ideologues, all of the limits fall away.