Activism

The Dishonest and Misogynistic Hate Campaign Against J.K. Rowling

And it turns out that she was, because despite the best efforts of her critics, she hasn’t yet been truly cancelled.

When J. K. Rowling first outed herself as a gender-critical feminist, my first thought was: If Rowling can be cancelled, anyone can be cancelled. Not only is she one of the best known and best loved authors in the world (the writer of children’s books, for goodness sake), she also has a personal history that ought to make her un-cancellable. This was the mum who escaped an abusive marriage and lived off benefits, writing the first Harry Potter book in an Edinburgh café while rocking her sleeping baby in a pram. This was the woman who became a billionaire, but then lost her billionaire status by giving away so much money to charity. If anyone was safe, Rowling should have been safe.

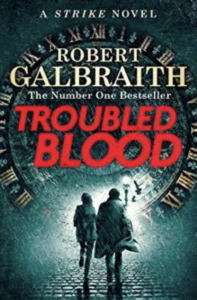

And it turns out that she was, because despite the best efforts of her critics, she hasn’t yet been truly cancelled. Her latest book, the murder mystery (written under the pen-name Robert Galbraith), was published on Tuesday and, as of Thursday, was number four on Amazon’s bestseller list for all literature and fiction. (In the UK, it sits at the number-one spot.) Sales of Harry Potter books also shot up over lockdown, despite the fact that, for more than a year now, Rowling’s name has been dragged through the mud on social media and in many news outlets. She has been condemned by actors such as Daniel Radcliffe, Rupert Grint, and Emma Watson, who became rich and famous only thanks to her success. And last month, she was pressured to return a human-rights award after she was accused of having “diminished the identity” of trans people. But although these undeserved attacks must sting, Rowling’s position as a bestselling author has survived—just as it will surely survive the fresh wave of controversy that arrived this week, following a lukewarm and misleading review of Troubled Blood in the Daily Telegraph that included this line:

The meat of the book is the investigation into a cold case: the disappearance of GP Margot Bamborough in 1974, thought to have been a victim of Dennis Creed, a transvestite serial killer. One wonders what critics of Rowling’s stance on trans issues will make of a book whose moral seems to be: Never trust a man in a dress.

As other critics have since pointed out, “never trust a man in a dress” is very much not the moral of the book, and the Creed character is never described as a transvestite, or transgender, or trans-anything, in fact. He never even wears a dress, but instead disguises himself in a feminine coat and wig when approaching one of his victims. Although fetishistic cross-dressing is sometimes a behaviour exhibited by sexually-motivated murderers—the most famous being Ed Gein and Jerry Brudos, who provided inspiration for the Buffalo Bill character in Silence of the Lambs—Rowling doesn’t portray her murderer as trans, and so doesn’t employ the “trans woman as serial killer” trope, as she has been accused of doing. In fact, the only trans character to appear in the Cormoran Strike series (of which Troubled Blood is the latest instalment) is a highly sympathetic and vulnerable young trans woman who plays a small role in The Silk Worm.

Not that the facts matter to those stepping up the hate campaign against Rowling, of course. Activists in this area are not known for their restraint. To the already relentless abuse directed at Rowling has been added the #RIPJKRowling hashtag, which is now trending on Twitter. “Does anyone need firewood this winter! JK’s new book is perfect to burn next to a Romantic fire,” tweeted the Irish musical duo Jedward. Other social-media users obliged by posting footage of themselves doing just that.

What has Rowling done to deserve all of this? Well, let’s run through the list of her supposed crimes. First, in 2018, she liked a couple of tweets written by gender-critical feminists—which is to say, feminists who reject the idea that gender self-identification can serve to erase the reality of human biology—including one tweet protesting against sexism in the Labour Party. Next, she sent a very restrained tweet in December 2019, expressing her support for Maya Forstater, a British woman who lost her job as a result of her gender-critical views. Rowling’s tweet read: “Dress however you please. Call yourself whatever you like. Sleep with any consenting adult who’ll have you. Live your best life in peace and security. But force women out of their jobs for stating that sex is real?”

Six months later, she followed up with another restrained tweet, this time in response to an article that used the term “people who menstruate” in the headline: “’People who menstruate.’ I’m sure there used to be a word for those people. Someone help me out. Wumben? Wimpund? Woomud?”

A few days after that, Rowling published an essay on her website explaining the reasoning behind these controversial tweets. The essay is well worth reading in full, particularly for anyone new to the conflict between gender-critical feminists and trans activists, since Rowling lays out the issues with clarity and compassion. (She is, after all, an exceptionally talented writer). She also wrote for the first time about her own experiences of sexual and domestic violence, as part of a longer section on the empathy she feels for trans victims of abuse:

If you could come inside my head and understand what I feel when I read about a trans woman dying at the hands of a violent man, you’d find solidarity and kinship. I have a visceral sense of the terror in which those trans women will have spent their last seconds on earth, because I too have known moments of blind fear when I realised that the only thing keeping me alive was the shaky self-restraint of my attacker… I feel nothing but empathy and solidarity with trans women who’ve been abused by men. So I want trans women to be safe. At the same time, I do not want to make natal girls and women less safe.

In response to this essay, a male Labour shadow minister wrote that Rowling had “used” her experiences of violence to “undermine the rights of others.” Rowling also suffered the public humiliation of a front-page story in the Sun, in which her ex-husband reported that he was “not sorry” for assaulting her. She then faced a further intensification of the online abuse that had begun after those first forbidden “likes” on Twitter and has not let up since.

The feminist philosopher Rebecca Reilly Cooper has collected screenshots of some of the many aggressive tweets that either include Rowling’s name or were sent directly to her. Clear themes emerge, “shut the fuck up,” being one. The words “bitch,” “whore,” “hag,” and (ah yes) “Karen” start to give the game away. Many Twitter users seem to be convinced that Rowling’s gender-critical politics can be ascribed to her “stinky” or “dry pussy,” and suggest that she needs to be “fucking punched”. Others write messages like “suck my fat cock and choke on it” or (with no hint of self-awareness) “JK Rowling can suck my big transgender cock.” Have you spotted the pattern yet?

Through all of this, Rowling has also attracted a lot of support—in fact, probably more support than criticism (though you wouldn’t always know that from headlines that suggest otherwise). As she described in a second essay on her site: “Since I first joined the public debate on gender identity and women’s rights, I’ve been overwhelmed by the thousands of private emails of support I’ve received from people affected by these issues, both within and without the trans community, many of whom feel vulnerable and afraid because of the toxicity surrounding this discussion.”

She is now a heroine in the eyes of many gender critical people—including gender-critical trans people—and some have said so very publicly. “I heart JK Rowling” advertising posters have been popping up all over the world, paid for by gender-critical feminists. They have been met with official resistance. One was removed from a railway station in Edinburgh by state-owned Network Rail, despite there being zero public complaints. And last week, another in Vancouver was defaced and then taken down. These posters said nothing except “I heart JK Rowling”: No other slogan, no link to a website, nothing. That’s how toxic her name has become, according to some.

Critics of Rowling have chosen to highlight a small detail in Troubled Blood that has very little to do with the plot of the book. In doing so, they’ve also chosen to ignore a much larger theme that runs through not only this instalment, but through the Robert Galbraith series as a whole. That theme is misogyny, a topic that Rowling is all too familiar with, given both her personal history and her recent monstering. If her critics had actually read her work (or, in the case of the Telegraph review, summarized it competently), they would have discovered a series of books that offer what the feminist writer Joan Smith describes as a “panoramic view of the extent of violence against women and girls.” Fortunately, the popularity of Troubled Blood makes clear that members of the reading public are still eager to read Rowling’s work. Her critics have tried very, very hard to cancel her. But they still haven’t managed it.

Correction: An earlier version of this article indicated that Ms. Rowling was “forced” to return a human-rights award. It is more accurate to say that she was “pressured” to do so, as the article now states.