Books

Corruption and Remorse—The Novels of a Watergate Conspirator

As an avid reader of pop fiction, I’m more partial to the Nixon administration than any other White House. The Reagan years may have produced more crooks, and the Trump years may have produced more chaos, but there is one measure by which the criminal and criminal-adjacent members of the Nixon White House were far more productive: they produced a hell of a lot more novels. In May 1976, disgraced vice president Spiro Agnew published his first and only novel, The Canfield Decision, about a sitting US vice president pondering his own run for the White House. This was followed in January 1977 by a political thriller entitled Full Disclosure from Nixon and Agnew’s former speechwriter William Safire. Safire would go on to write three more novels—Freedom (a massive Civil War epic), Sleeper Spy (an espionage thriller), and Scandalmonger (about muckraking journalists in the age of Thomas Jefferson).

G. Gordon Liddy, one of the masterminds of the Watergate break-in who served 52 months behind bars before the balance of his sentence was commuted by President Carter, wrote two thrillers: Out of Control (1979) and The Monkey Handlers (1990). The most prolific fiction writer associated with Watergate was former CIA agent E. Howard Hunt, who spent 33 months in jail for helping to plot the Watergate break-in with Liddy, and managed to produce 73 books during his lifetime, many of which were crime and spy novels. The first member of the Nixon White House to go to prison for his Watergate involvement was Charles Colson. Known as Nixon’s “hatchet man,” Colson worked with some of the most dishonest right-wing politicians of the 20th century, and then spent the rest of his life writing books are about the dishonesty of the American Left. He also produced one novel, a 1995 political thriller called Gideon’s Torch, co-written with Ellen Vaughn. But the Watergate figure whose fiction most merits attention was John Ehrlichman.

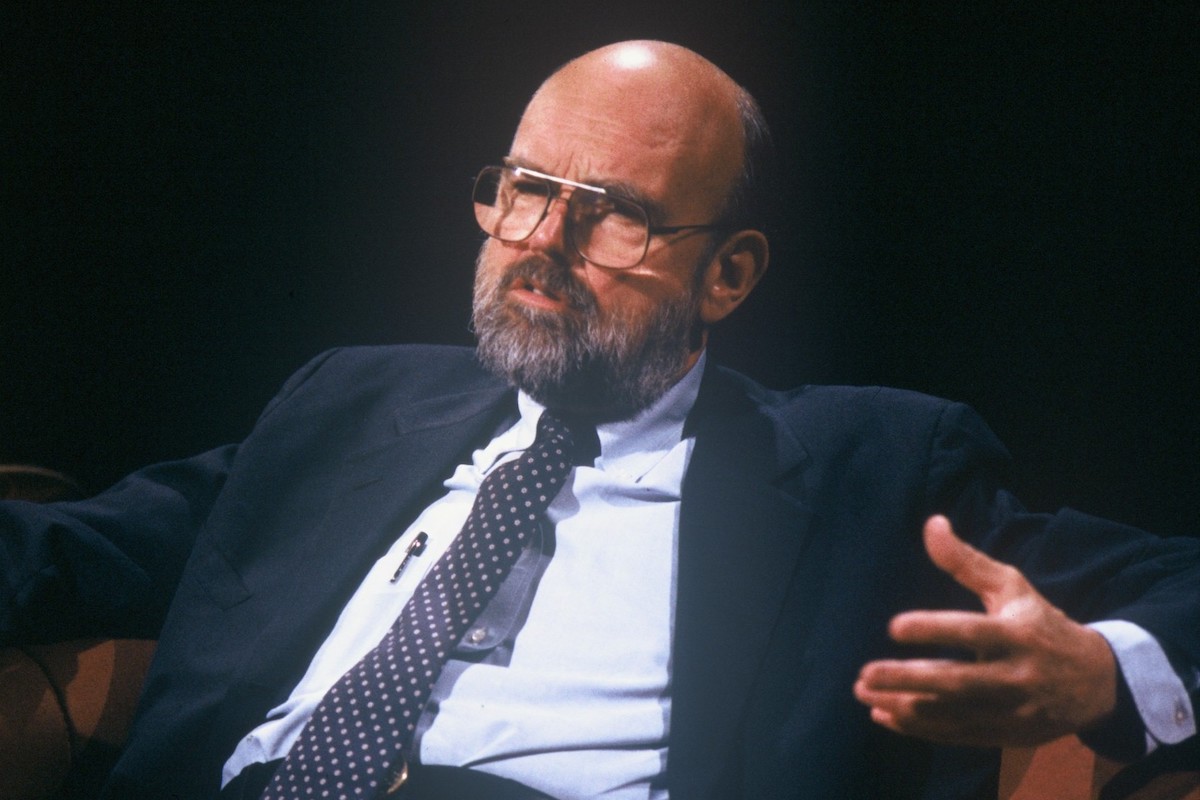

It’s not hard to understand why critics, columnists, and pundits never really warmed to Ehrlichman. Even before the Watergate story broke, he was reviled by many reporters and even by other members of the Nixon administration because he and his former UCLA classmate H.R. “Bob” Haldeman expended a lot of energy keeping the press as well as various White House insiders (John Dean, for instance) away from Nixon. As a result—and because their names sounded German—Haldeman and Ehrlichman were nicknamed “The Berlin Wall.” What’s more, both men adopted the permanently surly expression of the president they served.

I’ve always felt some fondness for Ehrlichman because, like me, he was born in the state of Washington, moved with his family to California, and was a Boy Scout. Sadly, that’s where the similarities end. Ehrlichman was not only a Boy Scout, but also an Eagle Scout (so was Haldeman), the highest rank attainable in American Scouting. He was one of the earliest winners of the Distinguished Eagle Scout Award, a rare honor established in 1969 and given to adults who have been Eagle Scouts and have distinguished themselves for at least 25 years in their chosen profession. Ehrlichman, who enlisted in the Army at age 18, won the Distinguished Flying Cross for participating in 26 bombing missions over Germany during the Second World War (a modest man, he devoted all of one sentence of his memoirs to his military career). He graduated from UCLA in 1948 with a degree in Political Science. A few years later he graduated from Stanford Law School. He then began his law career at a firm in Seattle, where he specialized in land use and developed a reputation as a fighter for environmental causes (which was not all that unusual for a Republican of the time—it was Nixon who proposed and created the US Environmental Protection Agency).

In 1960, Ehrlichman’s old college buddy Haldeman, now a prominent advertising executive, went to work on the Nixon Presidential campaign and recruited Ehrlichman to the cause (Haldeman is believed by many, including his son Hank, to have been the inspiration for Mad Men’s Don Draper, a fictional ad exec whom we first meet when he is working on Nixon’s 1960 presidential campaign). Nixon lost that race to John F. Kennedy by less than one percent of the vote. In 1962, Haldeman managed Nixon’s campaign for governor of California and once again enlisted Ehrlichman’s help. After Nixon lost that race to Pat Brown, most national political pundits declared his political career over. But when Nixon ran for president again in 1968, the two men rejoined his campaign and were rewarded with important jobs in his administration.

Alas, once he was ensconced in the White House, Ehrlichman seemed to lose his Eagle Scout sense of honor, duty, and civic responsibility. Like his boss, he became secretive, unscrupulous, and convinced that enemies within the press and the federal bureaucracy (now often referred to as the “deep state”) were plotting to bring the administration down. It was Ehrlichman, acting upon Nixon’s orders, who established the White House Special Investigations Unit, a group of covert operators dedicated to discrediting those damaging the administration by leaking information to the press (because they were plugging leaks, the men of the Special Investigations Unit were jokingly referred to as the White House plumbers). Eventually the plumbers would break into the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee at the Watergate complex. Ehrlichman had more to do with initiating the Watergate scandal than almost anyone else in the White House besides Richard Nixon himself. He was also a key architect of Nixon’s cover-up efforts.

* * *

But Ehrlichman did not spend his entire White House career breaking laws. As Nixon’s chief of domestic policy, he fought for some fairly progressive causes including workers’ rights, sovereignty for Native American tribes, and Affirmative Action, as well as the aforementioned environmental-protection agenda. After the Watergate scandal broke, he was convicted of obstruction of justice, perjury, and various other crimes, and sentenced to a jail term of up to eight years. While waiting for the appeals process to play out, and hoping for a pardon from Nixon, Ehrlichman left his wife and five children and moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico, where he grew a bushy biker beard and set about writing a novel in the hope of making enough money to cover the cost incurred by his legal woes. The book he wrote, The Company, sold more than a million copies and was made into a twelve-and-a-half-hour, six-part ABC-TV miniseries called Washington: Behind Closed Doors. Eager to get on with his life and his new writing career, Ehrlichman decided to voluntarily enter prison while the appeals process was ongoing. He served 18 months at a low-security federal prison near Safford, Arizona. And it was there that his rehabilitation truly began.

The August 1979 issue of Esquire magazine featured a long personal essay by Ehrlichman titled, “Mexican Aliens Aren’t a Problem… They’re a Solution,” in which he argued that American judges should not jail anyone whose only crime was entering the country illegally. The essay is a moving account of how Ehrlichman lived alongside several hundred illegal immigrants during his incarceration, how he started out fearful of them but eventually grew to like many of them, and perform legal work on their behalf. The article points out many of the injustices perpetrated by the legal system against undocumented workers. Many of these men had no idea what they were in prison for, or how long, because they were not provided with an interpreter at their trials. Most of the men, it turned out, were serving sentences of five months and 29 days because, if a prisoner served a sentence of six months or longer in a federal prison, he was entitled to some meager benefits when his sentence ended. Ehrlichman also noted that the much wealthier American landowners who hired the illegal aliens were never charged with a crime.

Ehrlichman was never a hardcore right-winger, not even during his White House years. Historian Theodore H. White, author of The Making of the President 1972, noted that Ehrlichman’s office “was one of the few at the [Nixon] White House where ideas were seriously entertained—good ideas, too, on energy, on land-use policy, on urbanization, on preservation of the American environment.” After his release from prison, Ehrlichman practically became a liberal squish. (Even Nixon, who helped pass the 1957 Civil Rights act, championed universal healthcare policies and environmental protection, and supported President Johnson’s Civil Rights, Voting Rights, and Fair Housing Acts, would probably be categorized as a Clintonian Democrat were he alive today.) Having paid his debt to society, Ehrlichman, now divorced, returned to Santa Fe, remarried, had a sixth child, and continued to pursue a career as a thriller writer.

The Company is, unsurprisingly, Ehrlichman’s weakest novel. It appears to have been written in a hurry, which is understandable since he had a prison sentence pending, and the plot is fairly rudimentary. The main character, William Martin, is a CIA director (apparently modeled on former CIA director Richard Helms) who once approved the unlawful assassination of a foreign national while serving a young liberal American president (modeled on JFK) killed before his first term ended. Now a new president is heading to the White House, a man named Dick Monkton (modeled on Nixon) and in order to protect himself from prosecution, William Martin must hang on to his job as CIA director, so that he can keep a hostile successor from discovering the truth about the assassination in the CIA’s files. To do this, he employs CIA personnel and hardware to secretly capture photos and audiotapes of the new president’s henchmen committing unlawful break-ins and warrantless wire-tappings of various leftwing journalists, State Department bureaucrats, and other presumed enemies of the president.

The dramatic climax of the novel comes when Martin visits Monkton at Camp David, the presidential retreat located in the state of Maryland. By this point, President Monkton knows about Martin’s involvement in the assassination and Martin has proof of various Watergate-like operations authorized by the White House. While the two men wander the grounds of the compound (so as to avoid being overheard by any listening devices that might have been planted indoors), they realize that they each have enough information to destroy the other, and so they come to a mutually satisfactory truce that allows them both to hang on to their jobs. What makes the book fascinating, even today, is the amount of insider knowledge Ehrlichman brought to the task of writing it. The reader is given a view of how the White House operates, and how the CIA and FBI operate, how Washington society works, and even how the retreat at Camp David is laid out that no writer of popular fiction had previously been able to provide. Here is just one example of Ehrlichman’s insights, a very brief scene in which Tallford, an aide to the president-elect, is speaking to Martin and one of Martin’s aides, Simon Cappell, two men whom Tallford suspects he someday might want to deny knowing:

Tallford gestured to the other man. “I understand you’re going to see Bailey. The agent here will take you to him. I must ask you to excuse me. I’m overdue downstairs. It was very good to have seen you, gentlemen.” The Washington Hedge, thought Simon Cappell: he uses “seen,” not “met” or “been introduced.” “Good to have seen you!”

“Nice to have seen you too,” said Simon wryly.

While in prison, Ehrlichman began work on his second novel, The Whole Truth. This novel is, in many ways, simply a retelling of The Company (a botched CIA assassination attempt of a foreign national leads to a game of cat-and-mouse between a sitting US president and one of his aides). But The Whole Truth is a vast improvement on the earlier novel. Ehrlichman clearly took his time with this book, and it shows. The characters are more fully developed, the dialog is better, and the plot is complex but still plausible. And it contains even more fascinating insider information about the US government than did its predecessor.

The hero of the book is Robin Warren, a young lawyer who works in the administration of Republican President Hugh Frankling. The president uses Warren as a go-between with the CIA, telling Warren that he doesn’t want to communicate with the agency via letter or phone call because he doesn’t want to leave behind a potentially dangerous trail of paper or wire-tapped phone recordings. Warren, flattered by the president’s faith in him, fails to realize at first what a precarious position he is in. Eventually, the president tells Warren to green-light a CIA operation that will bring down a military junta in Uruguay. When the operation goes badly awry, the president claims to have had no hand in it. He blames the disaster on Warren, whom he paints as an overzealous minor White House flunky who decided to push his own agenda by giving the CIA false orders from the president.

The Democratic-controlled Senate insists on holding televised hearings clearly modeled on the Watergate proceedings, and Warren becomes the reluctant star of these hearings in much the same way as John Dean became an early star of Watergate. Presiding over the hearing is Harley Oates, a drawling Democratic senator from the Deep South obviously patterned after real-life Senator Sam Ervin, Jr., who presided over the Senate’s Watergate investigation. The portrait is not meant to flatter Ervin. Oates is a preening phony, waxing poetic about the sanctity of the US Constitution while secretly accepting bribes from the president and the attorney general in exchange for steering the inquiry away from the White House. Ervin was indeed a Constitutional scholar. He also had a tendency to preen before the cameras. After Watergate made him famous he cashed in shamelessly, even producing a hideous spoken-word 45-rpm single of Simon and Garfunkle’s “Bridge Over Troubled Water.” But Ervin was not a crook. And he appears to have been angered by Ehrlichman’s fictional portrait of him. Ehrlichman’s The Whole Truth was published in May 1979. In December 1980, Ervin came out with his own nonfiction account of Watergate and appended Ehrlichman’s title to it: The Whole Truth.

Ervin might not have liked it, but critics mostly approved of Ehrlichman’s second novel. Kirkus Reviews’ unnamed critic wrote: “Ehrlichman has wrapped his basic narrative flair around scores of behind-the-scenes goodies and dozens of hints of further Nixon-era nastiness—a combination that’s likely to prove that The Company wasn’t just a first-time-lucky fluke.” The Whole Truth is a cerebral thriller that employs no violence or gunplay at all, just a lot of fascinating facts about the government that could only have come from the pen of a writer with an insider’s knowledge of Washington, D.C., the White House, and the Congress. Sadly, the book did not sell as well as The Company. By 1979, Watergate was old news and Ehrlichman was no longer a household name. Curiously, the fifth bestselling novel of 1979 was Jailbird, Kurt Vonnegut’s tale of a fictional minor Watergate felon newly released from prison. As an evocation of the Watergate era and its aftermath, Jailbird is good, but The Whole Truth is better—a meditation on the scandal and a riveting thriller.

Ehrlichman’s next book was his memoir, Witness to Power: The Nixon Years, published in 1982. The book is widely regarded as the best of the Watergate memoirs, most of which were cranked out in a hurry just to make a buck or to pass the buck. Prolific book reviewer John Barkham wrote: “John Ehrlichman, a key member of President Nixon’s Praetorian Guard, is the last and frankest of the Watergate principals to lift the veil on life in the White House during the Nixon years… He deserves credit for having told us more about the embattled Nixon White House than anyone else involved.” Christopher Lehmann-Haupt, reviewing the book for the New York Times, described it as “accusatory, funny, revelatory, apologetic, vindictive, analytic, and mournful.” In his conclusion, he notes:

Given the emotional buffeting we’ve taken from all the Watergate books—from the slick manipulation of John W. Dean 3d’s Blind Ambition (a project that Mr. Ehrlichman understandably excoriates) to the evasiveness of Mr. Nixon’s own RN—we could be forgiven for suspecting Mr. Ehrlichman of calculating his effects. But somehow we don’t. We get a sense that he, of all the conspirators, has learned and changed.

However, precisely because he was the last of the major Watergate memoirists, publishing his recollections nearly 10 years after the heyday of Watergate fever, at a time when the public had grown tired of Nixon-era memoirs, Ehrlichman’s book sold nowhere near as many copies as earlier Nixon-related titles did. Among the 10 bestselling nonfiction titles of 1976 were Woodward and Bernstein’s The Final Days (the year’s number one bestseller), Charles Colson’s Born Again (number five), John Dean’s Blind Ambition: The White House Years (number eight), and The Right and the Power: The Prosecution of Watergate by Leon Jaworski (number 10). But by 1982, Americans had lost their appetite for political nonfictions—the bestselling nonfiction work that year was Jane Fonda’s Workout Book. Also on the list were two different Weight Watchers cookbooks, The Richard Simmons Never Say Diet Cookbook, and The G Spot and Other Recent Discoveries About Human Sexuality, by a trio of researchers. Ehrlichman’s memoir was nowhere to be found.

Undaunted, Ehrlichman went to work on another thriller. He spent years researching his third novel, traveling all across China and elsewhere to get the details right. Published in May of 1986, The China Card is Ehrlichman’s best and biggest book. It is a political thriller set against the backdrop of Nixon’s efforts to renew the American diplomatic ties to China that were severed in 1949. This time, Ehrlichman doesn’t bother disguising his Nixon White House cronies behind aliases and fictional likenesses. Here Richard Nixon plays Richard Nixon, Henry Kissinger plays Henry Kissinger, and H.R. Haldeman plays H.R. Haldeman. Also appearing as themselves in this novel are Mao Tse-tung, Chou En-lai, and Soong Ching-Ling (the widow of Sun Yat-Sen). Ehrlichman seems to be the only novelist who understood the grand operatic nature of Nixon’s historic 1972 visit to China. A year after The China Card was published, Nixon in China, an opera by composer John Adams and librettist Alice Goodman, made its debut at the Houston Grand Opera, validating Ehrlichman’s belief in the dramatic potential of the event. The opera is not based on Ehrlichman’s novel, but it covers much of the same ground. Neither the novel nor the opera was an immediate critical success. Though the opera is now considered a modern masterpiece, it received decidedly mixed reviews in its original run. The New York Times dismissed it as “fluff” and “worth a few giggles but hardly a strong candidate for the standard repertory.” Critic Marvin Kitman noted that there were only three things wrong with the opera: the libretto, the music, and the direction. “Outside of that, it’s perfect,” he snarked.

Ehrlichman’s book got the same kind of reception. Kirkus Reviews, which had enthusiastically greeted his two earlier novels, called The China Card “padded and contrived… heavy with self-importance but light on originality.” Charles Trueheart, who reviewed the book negatively for the Los Angeles Times, didn’t seem to pay much attention to what he was reading. At one point he suggested that the character Wang Li-fa, a Chinese woman in her early 20s, “might be played convincingly by Tuesday Weld,” a blond Caucasian actress who was 43 years old in 1986. Sadly, The China Card never got the kind of critical reassessment that has made a modern classic of Nixon in China.

* * *

In the 1970s, legions of young Americans were inspired by the exploits of Woodward and Bernstein (particularly as they were embodied by Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman in the Alan J. Pakula film All the President’s Men) to seek careers in journalism. By 1986, many of those young would-be “Woodsteins” were ensconced in the highest levels of American journalism, and they all seemed to share a contempt for Nixon and his cronies. Nicholas Kristof, of the New York Times, was one of those young journalists. At about the time that The China Card was published, Kristof wrote a piece for the Times entitled “The Success of the ‘President’s Men,’” which briefly reported on what the likes of Ehrlichman, Haldeman, Liddy, Hunt, Colson, and other Watergate felons were doing nearly a decade and a half after the break-in at the Democratic National Headquarters. Kristof seemed to be saddened to learn that, for the most part, all the president’s men were doing fine, thank you. They were writing books, running businesses, traveling the lecture circuit, appearing on TV news shows and talk radio, and basically using their former notoriety to their advantage. The China Card seems to have suffered as a result of Nicholas Kristof Syndrome—the tendency among young Reagan-era journalists to resent the success of the men whose crimes had made Woodward and Bernstein famous.

In a very small way, I was a part of the wave of young Americans who became journalists because of their youthful fascination with Watergate. I am the same age as Nicholas Kristof and, like him, grew up in Oregon (I moved to California with my parents when I was 18). Because I lacked a college degree, I couldn’t write for the Times or the Post, but I spent a good part of the 1980s writing stories for the Suttertown News, a crusading leftwing newspaper (alas, now defunct) in my hometown of Sacramento. My editor sent me all over town to cover city council meetings and utility district hearings. These were very boring assignments on which I always hoped to discover the germ of some sensational story but mostly ended up with a notebook full of nothing. Because of my fondness for good pop fiction, however, I had long since forgiven Ehrlichman for his Watergate involvement. And what his harshest critics couldn’t see was that his books were an ongoing condemnation of his own behavior as a White House senior advisor. From his prison cell, Ehrlichman sent an audio-taped statement to the US District Court in Washington, D.C., in which he said: “I abdicated my moral judgments and turned them over to somebody else. And if I had any advice for my kids, it would be to never—never, ever defer your moral judgments to anybody. I’m paying the price for that lack of willpower… That’s something that’s very personal. And it’s what a man has to hang on to.” This is a lesson that every one of his fictional counterparts ends up having to learn.

Here’s Ehrlichman describing the mindset of Matt Thompson, the main character of The China Card:

Since the days when he was a child he’d always tried to do right—to please his parents and teachers and the scoutmaster and others. It had been relatively easy to figure out what they wanted of him; each one wanted something different, but he was able to tailor his actions to their desires and be thought by each to be a “good boy.”

But [working in the Nixon White House] was a game of blindman’s bluff played out over a complex new terrain full of unseen holes; everyone playing for himself, each piously covering himself with the flag, or national security, or “the President’s best interest,” to justify what he was doing. How could a person know what they expected of him?

And here’s an exchange between Robin Warren, the main character of The Whole Truth, and his girlfriend Maggie (who calls him “Bird” because of his avian name):

“No, seriously, Bird. Look. There are two ways of thinking about a White House job like yours. One is that you are just a mechanic, doing whatever [President] Frankling and [White House Chief of Staff] Hale tell you to do. If you do as you’re told and never say no to anything they come up with, then at the end of the term you can join the board of the Kennedy Center or win the Medal of Freedom.”

“And the other way is to be a freethinker and raise hell, right?”

“The other way is to really serve the country and, incidentally, the President, by speaking out on the important issues, hiring and protecting bright, effective and controversial people for your staff, and always doing what you believe is right, regardless.”

“And get fired after two weeks.”

“That’s not such a bad thing if it happens for the right reasons.”

Later in the novel, when Robin is considering lying to the American people and taking the fall for Frankling’s wrongdoing in order to protect the office of the president, Maggie begs him not to do it and warns him of what the consequences would be: “You’d be a political ghost ship—a freak—blown overseas and back before the wind. You’ll be an empty vessel with no insides. A ghost. An exile.”

Ehrlichman knew what it was like to become such a ghost ship. All of his books are cautionary tales about what happens to a public servant when he puts his own political survival ahead of the public good. Kristof and various book reviewers seemed to resent Ehrlichman his success as a novelist (NPR’s Daniel Schorr once groused about the books by Watergate felons, “The wages of sin include royalties”), but what they were missing was that Ehrlichman was using his notoriety to try to steer others away from the path that led to his downfall. Had a less complicated figure than Ehrlichman—a liberal journalist, say—produced his three novels, those books would almost certainly now be regarded as among the best political fictions of their era.

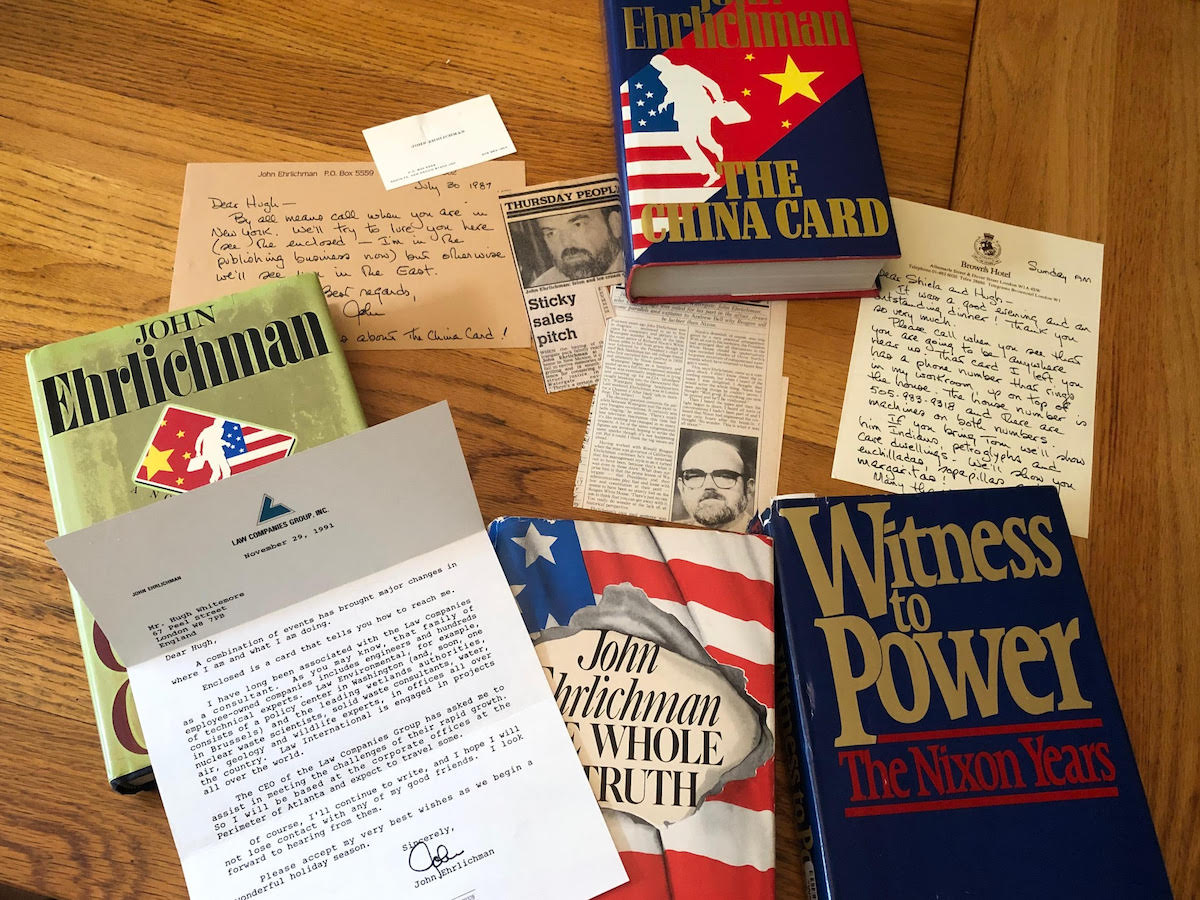

After The China Card, Ehrlichman hoped to produce more books. I know this because I’m probably the world’s only collector of John Ehrlichman memorabilia. Along with signed copies of his novels and one of his business cards, I also possess several letters that Ehrlichman wrote during his post-Watergate years. In one of those letters, dated November 29th, 1991, he tells a British friend of his that he has taken a job with an (now defunct) Atlanta law corporation that specializes in environmental issues. He describes his employer as a collection of “the leading wetlands authorities, nuclear waste scientists, solid waste consultants, water, air, geology, and wildlife experts… engaged in projects all over the world.” But he closes this account of his professional activities by assuring his friend, “Of course, I’ll continue to write.” Whether Ehrlichman wrote any more books after The China Card, I don’t know, but he didn’t publish any, despite living a further 13 years.

When he died, on Valentine’s Day, 1999, most of the obituaries carried headlines that were some variation of JOHN EHRLICHMAN, WATERGATE FELON, DEAD AT 73. None of them read JOHN EHRLICHMAN, WORLD WAR II HERO, DEAD AT 73. None of them read JOHN EHRLICHMAN, ENVIRONMENTALIST, DEAD AT 73. And none of them read JOHN EHRLICHMAN, NOVELIST, DEAD AT 73. In the end, he was remembered only for the worst thing he ever did.

If the pollsters are correct, another deeply corrupt American presidential administration will be coming to an end soon. However, it’s unlikely that the Trump administration will produce any writers of Ehrlichman’s stature. To date, none of the memoirs that have come from ex-members of the administration sound as if they are at all self-critical. Mostly, they seem to excoriate Trump while justifying the author’s own brief tenure in the White House. I expect most of the future memoirs to be equally as self-exculpatory. And it seems implausible that Roger Stone or Michael Cohen or Paul Manafort will ever have the self-awareness, the humility, or the talent to turn his experiences into gripping novels designed to warn the reader away from the path that led to the writer’s own disgrace. Oh, I’m sure we’ll get plenty of fiction from all the president’s men and women, but it won’t be packaged as such.