Latin America

Four Decades of Terror: Rio de Janeiro’s Never-Ending 'Drug War'

Rio’s futile, endless war will continue. Like going to the beach, or dancing samba, waging war is a way of life in Rio de Janeiro.

Welcome to Rio de Janeiro. Late August 2020. A woman tries to keep her child quiet. She is using her phone to film silhouettes moving past her glass front door. There is no mistaking the swift, purposeful shadows. Hunkering down, they point assault rifles and machine guns. During the short, chilling clip at least nine men run past. They are so-called “drug soldiers” from one of Rio’s famous favela communities, in the process of invading another. The invasion led to hours of gun battles, hostage-taking incidents and the death of Ana Cristina da Silva, a 25-year-old mother (not the woman in the clip), as she protected her toddler from bullets. It took place a short walk from the business district and was the latest episode in the city’s four-decades-old “drug war,” one of the world’s most intractable urban armed conflicts.

Millions—a quarter of cariocas (Rio residents)—live in more than a thousand favelas in metropolitan Rio. Heartbreakingly, these tight-knit micro-societies are some of the most violent urban areas in the world. Essentially, endemic violence serves to dominate and subjugate these communities, thus preserving Brazil’s unequal and racist social pyramid. No two favelas in Rio are the same. Each has its own idiosyncratic racial, social, cultural, and geographical formation. Social exclusion is the common denominator that binds together their population.

As informal, self-built communities, favelas exist outside the regulated city. Services like water and electricity are typically pirated from the main grid and not paid for. The persistent failure of Brazil to incorporate favelas into official society keeps them vulnerable and condemned to exploitation by criminals, police, and politicians, in many cases these working together. Although the 20th-century drug boom worsened the situation, by entrenching violence and the interests of crime and corruption, it is far from a modern phenomenon.

Rio has always been an explosive city. In 1915, the celebrated carioca author Lima Barreto wrote: “Rio is like a vast bunker and we live with the constant menace of exploding, as if we were aboard a battleship, or living in a fortress full of terrible explosives.”1

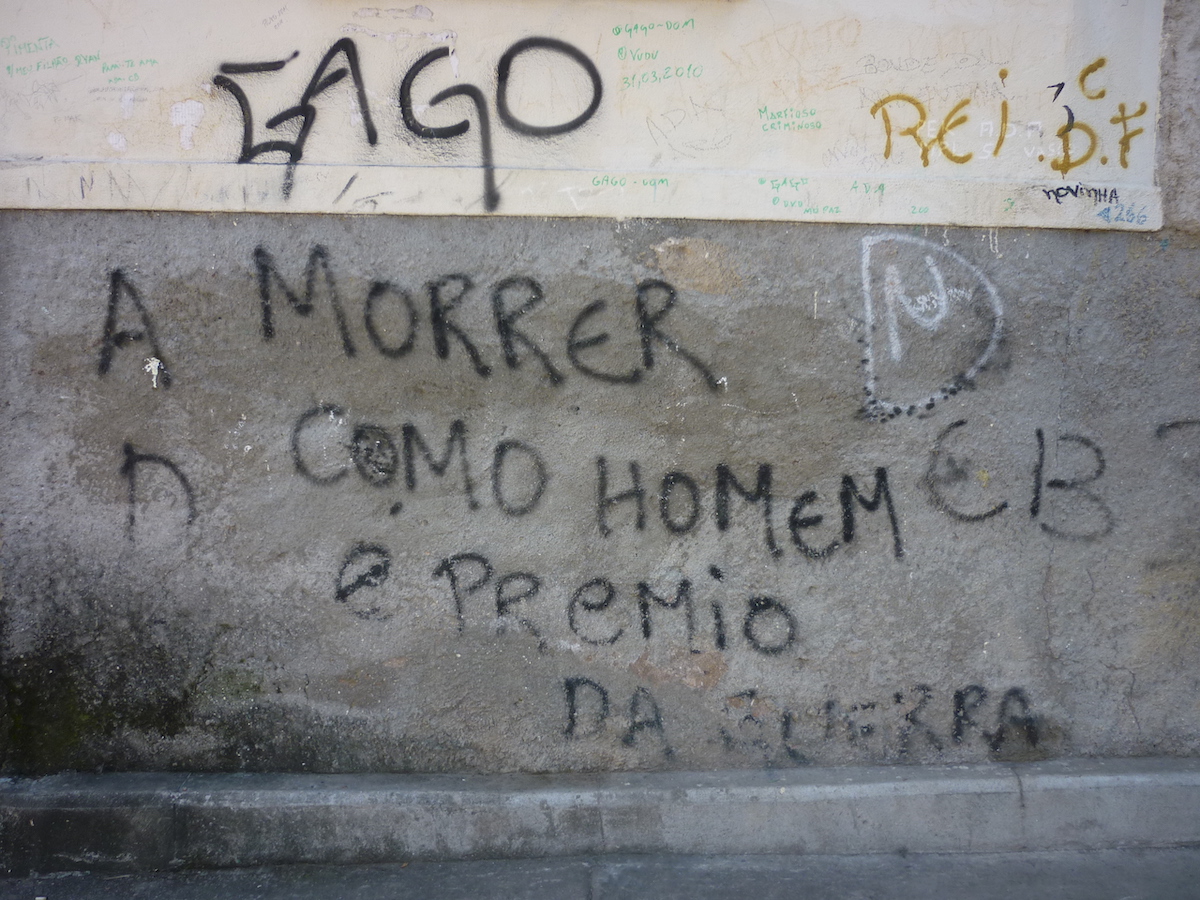

Today’s constant menace, the “war on drugs,” is mysterious and multidimensional. Fought against the backdrop of the city’s kaleidoscopic topography of sea, jungle, and mountain, this war constantly reinvents itself. Neither crisis nor emergency, it is a modus vivendi constructed on fear and hatred. Everything changes, and everything stays the same. The war maintains a tragic status quo, serving entrenched political, social, and economic interests. It keeps the city divided; the poor vulnerable and the rich powerful. Favela residents are treated like criminals, or at best, non-people to be ordered around. When the innocent die—and they often do—the authorities usually treat such loss of life as mere collateral damage.

Brazil’s war on its own people has deep and multiple roots; colonisation, genocide of the indigenous population, slavery, racism, and repression of social movements. The “war on drugs,” its modern manifestation, was born in the military dictatorship of the 1970s, when common criminals were held together with subversives on the Ilha Grande island prison, a few hours from Rio. According to a widely accepted version of events, the political prisoners influenced kidnappers, bank robbers, and drug dealers into organising themselves and creating a chain of command and hierarchy that brought order and discipline to prison life.2 The founders called their new organisation the Comando Vermelho (Red Command), or CV for short. The CV created rules for both inside and outside prison. They looked after offenders’ families and pooled resources. Crucially, the CV power structure extended into Rio’s favelas, which thus became aligned—in some cases through force—with the new criminal organisation.

At the same time, during the late 1970s and early 1980s, Rio de Janeiro became a hub for the international cocaine business, as demand for the drug increased in Europe and the US. During this boom period, spin-off local markets attended by favela-based drug sellers, who organised themselves according to CV rules, expanded rapidly. Dealers needed weapons to protect their product and earnings, from theft or attack by rivals and the police. Consequently, a symbiotic and lucrative trade in small arms and light weaponry grew in tandem with the drug businesses. As these dual markets took root in the favelas, they became inextricably linked to the CV, who as the local chiefs now exercised territorial control over communities awash with guns and drugs. Splits and betrayals led to the emergence of rival factions, the Terceiro Comando (Third Command) and the Amigos dos Amigos (Friends of Friends—the “friends” referred to here were shady police). By the end of the 1990s, what began as a cottage industry run by a handful of entrepreneurs peddling coke and grass with a discrete pistol shoved down their trousers, was now the dominion of highly organised, heavily-armed informal armies who—alongside corrupt lawmakers—disputed the substantial revenues of these illegal markets. The bodycounts skyrocketed.

Today, Rio’s “war on drugs” is both the pretext and euphemism for a war on the poor. Not a silent war of economic oppression and the subtle undermining of civil liberties and human rights, but a fire and brimstone, guns blazing, no prisoners taken, armed assault on the city’s most vulnerable. Encouraged to obey the rich and mistreat the poor, police are the only arm of the state to consistently reach inside the favela. Criminal police acting inside the official structure profit from extortion, arms and drug dealing, and kidnapping. Hidden within an institution that penetrates all the favelas in the city, they can act like businessmen, choosing which favelas to make alliances with, and which favelas to attack. Whether the police raid a favela or not depends on which faction dominates the community. Different factions have different connections.

Since 2005, illegal paramilitary groups, known locally simply as milícia (militia) and formed by off-duty or former police, firefighters, prison guards, and members of the armed forces, have scaled up the war of oppression, flushing out drug traffickers from communities and taking control. Once installed, the militia establishes itself as local security provider, charging all residents and businesses a “tax.” Militia leaders include city councillors and elected representatives in the state parliament. Because of their close ties to officialdom, police raids on militia areas, and consequent gun battles, are rare. However, militia members torture and kill innocent residents in order to spread fear in the communities they dominate.

Militias dominate Rio’s West Zone, which includes the opulent, aseptic Barra neighbourhood, home to the 2016 Olympic Park. The West Zone, where more than one-in-three of the city’s voters live, is a political power base. In 2008, a then-obscure Rio politician, Jair Bolsonaro, defended militias in a BBC interview, claiming they provided security, order, and discipline for poor communities.3 Their modus operandi suggested otherwise; in the West Zone favela of Barbante in 2008, hooded militia gunmen belonging to a group called “The League of Justice” executed seven residents at random, with the apparent aim of terrorising residents into voting for a particular candidate. But it is not just the poor and defenceless who risk their lives; in 2011 rogue police killed Patricia Acioli, a judge who had issued more than 60 arrest warrants to police suspected of militia and death squad activity. Jair Bolsonaro, longstanding West Zone resident, actual president of Brazil today, and his eldest son, Flávio, a senator, have a long record of association with police involved in militia activity.

There is nothing accidental about the status quo. It works very well for certain parties. In Drugs and Democracy in Rio de Janeiro, a formidable analysis of this toxic web of interests, CUNY professor Enrique Desmond Arias argues that crime and criminality are integral components of politics in Rio. He identifies the formation of illegal networks between residents’ associations (the only form of quasi-authority that exists in favelas), police, politicians, and criminals that sustain the conflict by creating a configuration of local “governance” that reinforces illegal activity. The formal state exercises violence by proxy through the drug traffic or the militia. Criminals dominating a given community act as local muscle; armed bullies who sustain a social order. To speak out or question their motives is to risk one’s life. Residents must see, hear, and speak no evil. Such malleable passivity is highly useful to politicians seeking votes, or wishing to do business with crime. Police corruption is normalised and integral to the process, to the extent that it can be easier for police to engage in illegal activity than to fight crime. Arias acutely observes that:

…police not on the take will face criminals who have intelligence about their activities from other police. Police who would normally not take bribes may start to take bribes out of a sense of hopelessness because it is less risky than actually trying to enforce the law when other police actively work with criminals, or because pervasive corruption renders corrupt activity one of the few ways of moving up the career ladder. This progressively undermines the rule of law, leads to higher levels of human rights abuse, and can pose profound challenges to democracy.4

Rio’s tragedy is symptomatic of Brazil’s entrenched violence. According to the Brazilian Forum for Public Security, there were 65,602 violent killings in the country during 2017. This total exceeds the official number of US military fatalities resulting from the Vietnam War (58,220). In 2018, killings by police in Brazil stood at 6,220—in Rio alone that year, police registered the killing of 1,538 alleged suspects in “confrontations.” In the light of such depressing statistics, it is hard to think positively of the future. In the meantime Rio’s futile, endless war will continue. Like going to the beach, or dancing samba, waging war is a way of life in Rio de Janeiro.

So where do these “drug war” drugs come from? Cocaine, particularly, is integral to the contemporary drama of Rio de Janeiro. It’s been that way for quite some time. Popular, early 20th-century chroniclers of Rio’s Belle Époque (well-educated, travelled men like flâneur Benjamin Costallat) documented the nocturnal decadence of the carioca establishment, particularly its men, who spent nights cavorting in environments where cocaine consumption was de rigeur. In 1924, Costallat wrote about the city’s cocaine neighbourhoods of Lapa and Glória, which at night “vibrated with light, the laughter of women, human spasms.” In Glória, Costallat finds a street dealer who sells him German produced “Merck” cocaine, which he then takes to a brothel run by a Madame called Gaby. When he gives her two tiny glass flasks of Merck, she greets them with “shining eyes” and a “visible shiver of diabolical pleasure.” Gaby, he observes, would probably deny bread to the poor, but if she needed drugs, she might even sell her last piece of jewellery.5

Cocaine remained a reasonably safe and popular drug for Rio’s elite right through to the 1960s. Then Brazil began to follow the US-led war on drugs and UN-endorsed anti-narcotic conventions. These political shifts pushed cocaine further underground and further, as the stakes involved in buying and selling the substance rose, into the hands of criminals and corrupt officials. The tipping point came in the 1970s when, despite prohibition, worldwide demand for the drug blossomed. International traffickers began to move large quantities of cocaine through Rio de Janeiro.

The remarkably beautiful Cláudia Lessin came of age in Rio’s well-to-do South Zone beach district in 1977. Disco fever was at its height. Her elder sister, Márcia, was a well-known local actor who starred in a film adaptation of Tom Jobim’s famous The Girl from Ipanema. The sisters came from a classic middle-class family, but their father, a civil aviation pilot, was not rich or powerful. They had lived in the same rented accommodation for 20 years. Claudia was sensitive and bright but, like many young people of any era, confused. Her father had recently travelled to the US to bring her home from Los Angeles where she had lived with Dusty, a gigolo boyfriend, and had been involved in all manner of scrapes. Back in Rio she plunged into a depression, stemmed only by psychoanalytic treatment and love for her cat Mouche.

She was just 21 when, one Monday morning, lifeguards found her naked corpse splayed on rocks at the Atlantic’s edge. The discovery of an unknown female body—a white body—in this prominent spot, gripped the nation. Who was she? Who had killed her, and why? Claudia, her face battered and disfigured, lay yards from the Avenida Niemeyer, an iconic cliff-side road.

If it had not been for a toothache, her murder might have gone unsolved. Indio, a migrant worker from Brazil’s north-east, was unable to sleep the night before the discovery of her body. Cursing his bad tooth outside the precarious shack he shared with two other labourers, Indio spotted two men behaving strangely on the edge of the Niemeyer and noted down their license plate number. The car belonged to Michel Frank, son of a millionaire industrialist. But when a no-nonsense detective called Jamil Warwar publicly named Frank and his friend Georges Khour, a society hairdresser, as prime suspects, superiors removed him from the case. An admiral and a public prosecutor offered and then withdrew an alibi for Frank. Rather than following up leads, police working on the case sought to slow it down. They did not carry out tests on the car, nor did they examine Frank, who had cuts on his hands and face. Eventually, Frank alleged that Cláudia had died after an orgy of drug taking; that he and Khour dumped her body in panic. But the state autopsy said she had not taken drugs or even ingested alcohol. Cláudia died from strangulation and head injuries. Following this revelation Michel Frank, who held dual nationality, fled to Switzerland.

Within a year of the murder, a prize-winning investigative journalist named Valério Meinel published a book entitled Because Cláudia Lessin Will Die. Meinel meticulously picked apart the web of lies to discover that Khour and Frank were cocaine middlemen. Meinel believed they tried to force Cláudia into sex, which she refused, threatening to expose what she had seen the night before in Frank’s flat, when he had received a large quantity of cocaine that he promptly passed on in front of her to numerous Leblon society characters. Bombed on drugs and fearful of what she might do, Frank killed Cláudia with his own hands. Khour helped to throw her body onto the cliffs in an attempt to fake the work of a sexual maniac. In 1980, the hairdresser, who had even cut little Cláudia’s hair as a child, was charged and imprisoned for accessory to murder. Frank remained in Switzerland where, in 1989, he was shot and killed by an unidentified assassin.

Naive young Cláudia’s horrific public death—her naked corpse, her beauty and lost innocence—was a grisly portent of the havoc that the cocaine business was to wreak on Rio. Valério Meinel understood the symbolic significance of the murder as well as the implications of the subsequent cover-up. His book is both an investigative tour de force and a fascinating portrait of the city at the end of the 1970s—that shines a bright, lucid light onto Rio’s impending explosion of drug-related violence. Meinel’s genius is to get under the skin of his characters. He understood the petty prejudices, hidden hierarchies and social discomforts that drove carioca society and made life impossible for people like the detective Warwar:

I don’t like Copacabana, nor anywhere in the South Zone. Everything is half-false, disguised by status. When I come up here, I always have the impression that some son-of-a-bitch is spying at me from a window the whole time. Things happen here that make me want to kick doors down and drag the culprit out. Like we do in the favela. There shouldn’t be any difference, crime is crime. But here you can’t. You have to be slippery, because everyone has a godfather. If we’re not careful, when we get back to the station there are more than ten phone calls from bigwigs demanding our heads on a plate. Me, I’m from the suburbs, and proud of the fact.6

Meinel shrewdly identified the lethal opportunities for quick money and social ascension that cocaine opened up in Rio’s torpid social matrix. And crucially, he dared to question the much-vaunted state and media contention that criminals from favelas were behind the wholesale cocaine trade.

But who did supply the suppliers? Where did people like Frank get their drugs? In Costallat’s 1920s, cocaine was imported to Rio from Europe for medicinal use. Ninety percent of it ended up on the black market, where an army of intermediaries and sellers distributed it across the city. According to Costallat, almost every profession—he cites chauffeurs, manicurists, barbers, dentists, doctors, fishmongers, waiters, gamblers, and even journalists—had its share of cocaine suppliers. But although he had a clear grasp of the machine’s interior workings, he wondered who was at the top of the business:

But all this cocaine, spread across all these social classes, has a major wholesaler. He’s the king of cocaine in Rio de Janeiro. He’s the great pretender. A mysterious person who no one knows, but who dominates the clandestine market for the drug, setting prices and organising, unpunished and anonymous, its distribution and criminal sale. This king of cocaine, king of this century’s great poison, with so many victims, must live surrounded by respectful peers. He must be rich and respected. He earns enough to be both things.7

In November 2013, a helicopter carrying 450 kilograms of unprocessed cocaine landed on a farm in Espírito Santo state, just north of Rio de Janeiro. Police filmed the landing, arresting the two pilots and two other men as they unloaded the drugs into a car. But when it transpired that the helicopter belonged to a powerful politician from Minas Gerais (a coffee-rich state larger than France) the investigation halted four days after the apprehension. In what appeared to be a cross between a cover-up and a damage-limitation exercise, police investigators called a press conference where they announced their conclusion that the cocaine had nothing to do with the member of the Minas Gerais state parliament, Gustavo Perrella, or his father Zezé Perrella, a federal government senator.

The Perrella family are one of Brazil’s most powerful political clans. Senator Zezé Perrella served four terms as president of an immensely popular football team, Cruzeiro, where one of the greatest living footballers, Ronaldo “Fenomeno,” began his career. When the police and mass media dropped the matter like a hot potato, the “Helicoca” case was very quickly consigned to yesterday. However, dogged independent journalists (you can find the revelatory subtitled “Helicoca” documentary here) discovered that the helicopter made a prior drop-off at a luxury hotel in São Paulo and that US DEA officers had visited the district judge in Espírito Santo to inform him that the drugs were probably Europe-bound. But by then the case was all but closed. The Perrella family denied all knowledge of the cocaine, laying the blame with the pilot, who they alleged had acted independently. But no one even arrested the pilot.

In Zero, Zero, Zero, an extensive analysis of the global power cocaine wields in the world today, organised crime investigator Roberto Saviano argues that there is no financial investment in the world that gives better returns than cocaine; it is easier to sell than gold, its revenues can exceed those of oil, and in a few years cocaine speculators can accumulate the wealth that commercial organisations could only hope to achieve in decades. Saviano also asserts that:

For the most powerful families coke works as easily as an ATM machine. You need to buy a shopping centre? Import some coke, and after a month you’ll have enough money to close the deal. You need to sway an election? Import some coke, and you’ll be ready in a few weeks.8

In Brazil, it’s as if the “Helicoca” never existed. It simply vanished from the public domain, along with the half tonne of drugs. A minor detail—once processed, the shipment would have had a street value of $100 million. Another minor detail—at the end of 2013, Brazil’s politicians, including the Perrella family, were gearing up for another costly election.

Today, greater and greater quantities of cocaine pass through Brazil to satiate Europe and Asia’s ever-increasing appetite for the super-stimulant. In 2015, Calabria’s ‘Ndrangheta mafia were thought to move 80 percent of European cocaine through the Brazilian port of Santos. Last year, a top ‘Ndrangheta boss was arrested in São Paulo. And in July 2019, a Brazilian Air Force sergeant, on a special flight accompanying President Bolsonaro to a G20 meeting, tried to wheel luggage containing 39kg of undisguised high quality cocaine through Spanish customs. He assured the officials who opened his suitcase that he was bringing cheese to a cousin. The sergeant, Manoel Silva Rodrigues, made 30 national and international trips for the Brazilian Air Force in five years.

Back in Rio de Janeiro, the so-called “drug war” continues to wreak homicidal havoc on its civilian population, as this Sky News report from last year demonstrates. A violent city is a frightening city. A frightening city is an insecure city, which means money for the bullies; money for the private security companies owned by high-ranking police; money for the weapons and munitions industry; money for corrupt officials who supply drugs and guns; and money for dealers who buy and distribute these within voiceless communities. The war keeps the poor on their knees. Despite its innate strength and resilience, war renders the favela traumatised, supplicant, and deferential; an easy target for cheap drugs and alcohol, corrupt politicians, consumer goods, junk food, junk TV, and feel-good religious quick fixes. Fé em Deus, the drug traffickers say. In God We Trust. And you had better trust in God because here there is no rule of law. Because that is how it’s meant to be.

Adapted from the author’s new book, Nothing by Accident: Brazil on the Edge (Independent Publishing Network, 2020).

References and Notes:

1 Author translation of Lima Barreto, Pólvora e Cocaína, 1915 in Cocaína, Resende e Soares, Casa da Palavra, Rio de Janeiro, 2006.

2 For a detailed history of the formation and rationale behind the Comando Vermelho see Gay, Robert. Bruno, Conversations with a Brazilian Drug Dealer (Duke University Press 2015).

3 Após defender legalização de paramilitares no passado, Bolsonaro agora se diz desinteressado no assunto. Marco Grilo and Thiago Prado in O Globo, July 8th, 2018.

4 Arias, Desmond Enrique. Drugs and Democracy in Rio de Janeiro, (University of North Carolina Press 2006) p.52.

5 Author translation from Benjamim Costallat, No Bairro da Cocaína, Mistérios do Rio (Biblioteca Carioca, 1990) p.22.

6 Author translation from Valério Meinel, Porque Claudia Lessin Vai Morrer (2 Ed. Editora Codecri, Rio 1978) p.49.

7 Author translation from Benjamim Costallat, op.cit, 1990, p.22.

8 Roberto Saviano, Zero, zero, zero, Chapter 5 (Penguin 2015).