Canada

On This Day in 1945, Japan Released Me from a POW Camp. Then US Pilots Saved My Life

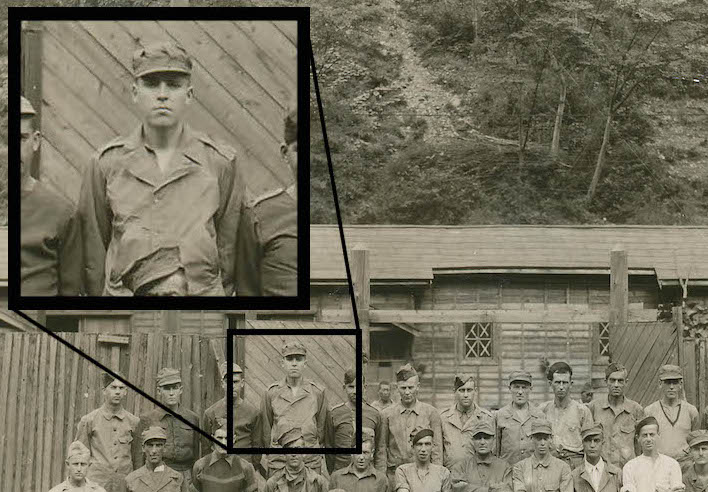

These were veterans of the long Pacific campaign. They’d survived many terrible encounters with the Japanese in their westward campaign across the Pacific, and they looked the part.

It was noon on August 15th, 1945. The Japanese Emperor had just announced to his people that his country had surrendered unconditionally to the Allied Powers.

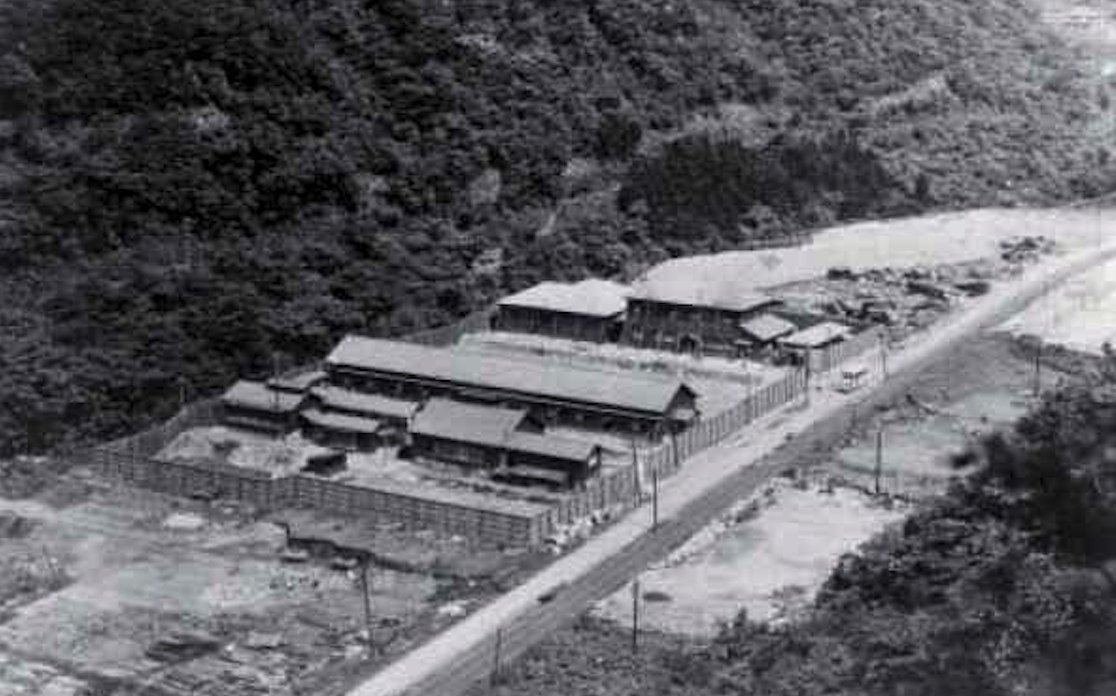

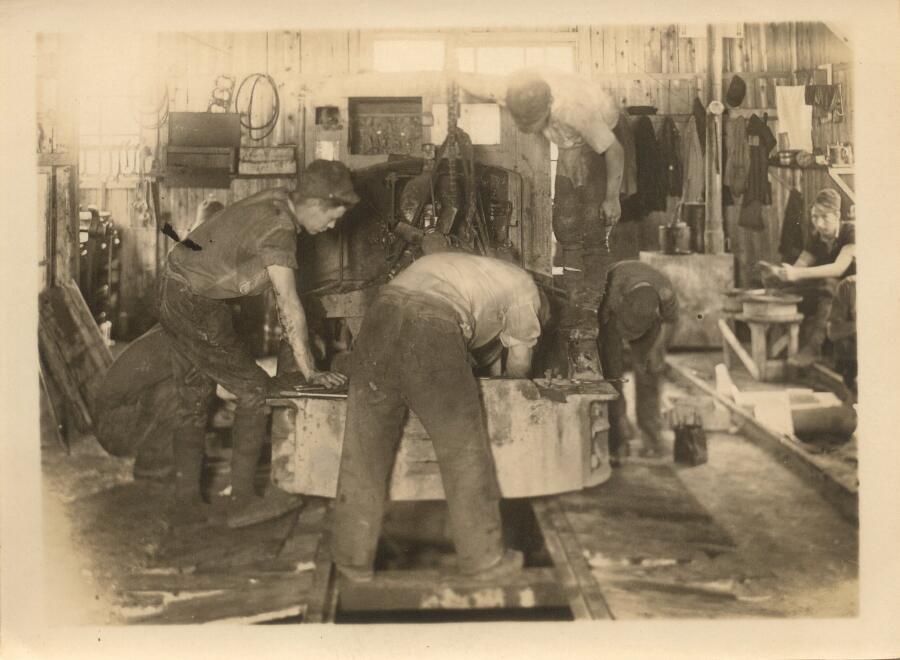

To those of us being held at Ohashi Prison Camp in the mountains of northern Japan, where we’d been prisoners of war performing forced labour at a local iron mine, this meant freedom. But freedom didn’t necessarily equate to safety. The camp’s 395 POWs, about half of them Canadians, were still under the effective control of Japanese troops. And so we began negotiating with them about what would happen next.

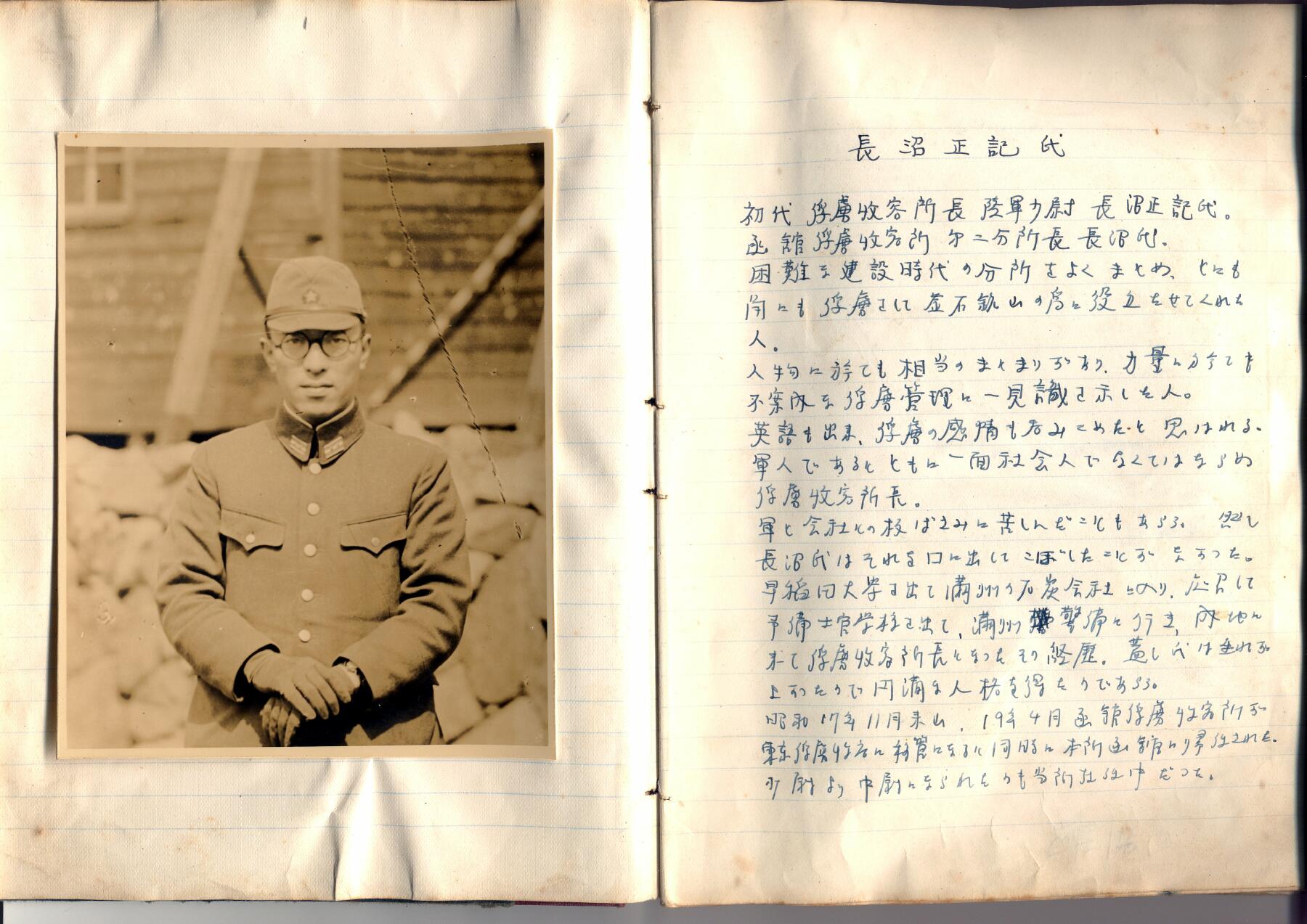

Complicating the negotiations was the Japanese military code of Bushido, which required an officer to die fighting or commit suicide (seppuku) rather than accept defeat. We also knew that the camp commander—First Lieutenant Yoshida Zenkichi—had written orders to kill his prisoners “by any means at his disposal” if their rescue seemed imminent. We also knew that we could all easily be deposited in a local mine shaft and then buried under thousands of tons of rock for all eternity without a trace.

We had no way of notifying Allied military commanders (who still hadn’t landed in Japan) as to the location of the camp (about a hundred miles north of Sendai, in a mountainous area near Honshu’s eastern coast), whose existence was then unknown. Because of the devastating American bombing, Japan’s cities had been reduced to rubble, its institutions were in chaos, and millions of Japanese were themselves close to starvation, much like us. The camp itself had food supplies, such as they were, for just three days.

Lieut. Zenkichi seemed angry, and felt humiliated by the surrender. Yet he appeared willing to negotiate our status. And after some stressful hours, we reached an agreement: The Japanese guards would be dismissed from the camp, while a detachment of Kenpeitai (the much feared Military Police) would provide security for Zenkichi, who would confine himself to his office.

To our delight, the local Japanese farmers were friendly, and agreed to give us food in exchange for some of the items we’d managed to loot from the camp’s remaining inventory—though, unfortunately, not enough to feed the camp. Meanwhile, through a secret radio we’d been operating, we learned that the Americans were going to conduct an aerial grid search of Japan’s islands for prison camps. We followed the broadcasted instructions and immediately painted “P.O.W.” in eight-foot-high white letters on the roof of the biggest hut.

Two days later, with all of our food gone, we heard a murmur from the direction of the ocean. The sound turned into the throb of a single-engine airplane flying at about 3,000 feet altitude. Then, suddenly he was above us—a little blue fighter with the white stars of the US Navy painted on its wings and fuselage. But the engine noise began to fade as he went right past us. Please, God, I thought—let him see our camp.

Then the engine sound grew stronger, and changed its pitch as we heard the roar of a dive. The pilot had wrapped around a nearby mountain and came straight down the centre of the valley, his engine now bellowing wide open. From just over treetop altitude, he flew over the centre of the camp. We all went wild: Our prayers had been answered.

Then he climbed to about 7,000 feet while circling above us—we assumed he was radioing our location to base—before making another pass over the camp, as slowly as he dared, this time with his canopy back. He threw out a silver tin box on a long streamer that landed in the centre of the camp. Inside, we found strips of fluorescent cloth and a hand-written note: “Lieutenant Claude Newton (Junior Grade), USS Carrier John Hancock. Reported location.”

The instructions for the cloth strips were as follows: “If you want Medicine, put out M. If you want Food, put out F. If you want Support, put out S.” We put out “F” and “M.” Once more, Lieut. Newton flew over the camp, this time to read the letters we’d written on the ground. Waggling his wings, he headed straight out to sea to his floating home, the John Hancock.

Seven hours later, two dozen airplanes approached the camp from the sea. They were painted with the same US Navy colours, but these were much larger planes—Grumman Avenger torpedo bombers with a crew of two. Each made two parachute cargo drops in the center of camp, leaving us with a ton or more of food and medicine. The boxes contained everything from powdered eggs to tins of pork and beans. There was also something called “Penicillin” that, I later learned, doctors had begun prescribing to infected patients in 1942. (Our camp doctor had understandably never heard of it.) That night, we had a feast and a party. Despite the doctor’s warnings not to overdo it, we did. The sudden calorie intake nearly killed us.

But it was one thing for the Americans to drop supplies, and another thing to get to us. The days passed, until one sunny morning we had another aerial visitor from the east. He circled the camp and dropped a note: “Goodbye from Hancock and good luck. Big Friends Come Tomorrow.”

The “friends” arrived at about 10am the next day, and they were indeed big: four-engine B-29 Superfortresses. Like the Penicillin, this was something new: These planes hadn’t entered service till 1944, and none of us had seen one.

Their giant bomb-bay doors opened and out came wooden platforms, each loaded with parachute-equipped 60-gallon drums. These were packed with tinned rations and other supplies, including new uniforms and footwear. None of this was lost on nearby Japanese villagers, who saw us POWs going from starvation to a state of plenty. Since our newfound wealth was scattered all over hell’s half acre, we asked these locals to bring us any drums they might find, which they did, in return for the nylon chutes (which local seamstresses and homemakers would put to good use) and a share of the food. That night, we had another party, except at this one, everyone was dressed in a new American uniform of his choice: Navy, Army, or Marine.

The next day brought another three lumbering aerial giants—from the Marianas Islands, it turned out. Again, the local Japanese residents helped us, amid much bowing, collect the aerial bounty. By now, the camp was beginning to look like an oil refinery, with unopened 60-gallon oil drums stacked everywhere.

When the daily ritual was repeated the day after that, some of the parachute lines snapped in the high winds, and the oil drums fell like giant rocks. Several hit the camp, went through the roofs of huts, hit the concrete floors and exploded. One was packed with canned peaches, and I don’t have to describe what the hut looked like. There were several very near-misses on our men, Japanese personnel and houses in the nearby village. When the next drop generated a similar result, I looked up to see that I was right under a cloud of falling 60-gallon oil drums. It was a terrifying moment. And I imagined the bizarre idea of surviving the enemy, surviving imprisonment, and then dying thanks to the kindness of well-meaning American pilots.

We now had tons of food and supplies—enough for months, and more was arriving. The camp had begun to look as if it had been shelled by artillery. So we painted two words on the roof: NO MORE! The next day, the big friends came from the Marianas and, as we watched from the safety of a nearby tunnel, they circled the camp and, without opening their bay doors, flew back out to sea, firing off red rockets to show they’d received the message.

It was a surreal scene. But it didn’t distract us from the fact that the generous and timely American response saved many of our lives. In the days that followed the drum showers, we settled down to caring for our sick and to some serious eating. Thanks to the US supplies, we began to gain a pound a day. The American generosity was especially notable given that few of the prisoners at Ohashi were American. Almost all were Canadian, Dutch, or British.

At about this time, I decided to go back to the nearby mine where we’d worked as prisoner labourers. I wanted to say goodbye to the foreman of the machine shop, a grandfatherly man who’d called me hanchō (squad leader), and had been as kind to me as the brutal rules of the country’s military dictatorship permitted. It was both joyous and sad. We were happy that the war was over, yet sad at the knowledge that this would be our last meeting. I promised him that I would take his earnest advice and return to school as soon as I got home. “Hanchō, you go Canada now,” he said.

I later learned that about three million Japanese soldiers and civilians lost their lives in the war. Millions more were left wounded. The country had been hit with two atomic bombs. Whole cities had been gutted by fire. At every level, the war had been an unmitigated disaster for Japan. Its people had become cannon fodder in a cruel and pointless project to conquer East Asia.

My fellow ex-POWs and I visited the camp graveyard, and said one last goodbye to our comrades who’d found their last resting place so far from home. It was an unjust reward for such brave young men. And it was then that tears I couldn’t control welled up in my eyes and streamed down my cheeks.

On September 14th, 30 days after Emperor Hirohito had publicly announced Japan’s surrender, a naval airplane flew in from the sea and dropped a note to inform us that an American naval task force would evacuate us on the following day. Sure enough, on September 15th, landing craft beached themselves and hastily disgorged a force of Marines. Their motorized column sped inland to the Ohashi camp, led by a Marine colonel and armed to the teeth.

These were veterans of the long Pacific campaign. They’d survived many terrible encounters with the Japanese in their westward campaign across the Pacific, and they looked the part. After our captain saluted the colonel, they embraced, and the colonel told us how he planned to evacuate us, giving specific orders as to how it was all to be accomplished.

After he issued his orders, the Colonel asked, “Are there any questions?” Our captain said, “Yes, I have one. Sir. What in the hell took you so long to get here?” That at least brought a smile to those tough, weather-beaten Marine faces.

Following the Colonel’s instructions, we mounted up, said sayonara to Ohashi and, after almost four years of imprisonment, began the glorious journey home to our various loved ones. I was in the last vehicle that left the camp that day. And as we departed, I observed a compound that was now completely empty—save for one forlorn figure, who’d emerged from his office and now stood at the center of a camp that once held 400 men. It was Lieutenant Zenkichi.