Books

Chinese Science Fiction's Disaster Dystopias

Rather than the emergence of a China-dominated world order, as some in the West and many in Beijing propose, science fiction writers illuminate realities that could end up reprising the failures of the former Soviet Union.

The Great China dream will replace all private dreams.

~Ma Jian, China Dream

In Ma Jian’s new novel, the protagonist, Ma Daode, may be a corrupt, womanizing local official, but he is a corrupt, womanizing local official with a mission. His goal is to develop a drug that will allow President Xi Jinping’s vision of a glorious Chinese future to dominate not only citizens’ daily lives but their sleeping hours as well. This is his utopian quest. The China dream, Ma Daode suggests, “is not the selfish, individualist dream chased by Western countries. It is a dream of a people, a dream of the entire nation, united as one and gathered together into an invincible force.” This mindless worship of hierarchy and control permeates his thinking.

China Dream was published in 2018, three years before the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party, and it provides insights into the Middle Kingdom that are becoming harder to find as control of local media tightens. It is a product of the “golden age” of Chinese science fiction, notes the New Scientist, that has been able to transcend the controls increasingly imposed on most non-fiction writing and public discussion. Author Liu Cixin has argued that, unlike the earliest days of the genre during the last days of the Qing dynasty, Chinese science fiction no longer fits a science-based optimism underlying the Communist vision. Such views, he observes, have “almost completely vanished.”

Contemporary Chinese writers are continuing the tradition of anti-totalitarian science fiction. Yevgeny Zamyatin’s 1921 novel We explored the dangers of a Soviet regimented society dedicated to erasing the individual; the works of the Polish author Stanisław Lem identified the various underlying hypocrisies of the old Soviet Empire. Other classics, like George Orwell’s 1984 or Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, presaged developments still evident and threatening today.

Ma Jian now lives in London and sees his task as similar to that of Orwell. In his introduction to China Dream, he writes that Orwell “foretold it all.” Xi’s “national rejuvenation,” Ma adds in the Afterword, reprises the horrors of the last century—it requires complete control of the population’s thoughts and the elevation of the leader himself to demigod status. China’s race towards the perfect state, he warns, will produce the same result as the Soviet experiment: “Utopia,” he reminds us, “always leads to dystopia.”

The new global vision

Critically, the “Chinese dream,” like that of the late Soviet Union, is not only meant for local consumption. “If we meld traditional Chinese values with Marxist ideology,” Ma Daode’s party superior suggests to him, “the China dream will be embraced by every nation. The world unity so desired by Genghis Khan will be accomplished by our generation of Party leaders.” As China Dream suggests, the Middle Kingdom now represents the most profound philosophical challenge to liberal values since the end of the Cold War. And they are not without their Western admirers. Standard Chartered Bank, for example, predicts that China will surpass the US as the world’s largest economy as early as the end of this year.

This sense of China’s inevitable preeminence has been bolstered by the Western decline after the Great Recession, convulsions over climate change, and the COVID-19 pandemic, now thought by some analysts to have been a “triumph” for President Xi. “Western nations are not going to collapse, but the smooth operation and friendly nature of Western society will disappear, because inequity is going to explode,” predicts Jørgen Randers, a professor emeritus of climate strategy at the BI Norwegian Business School. “Democratic, liberal society will fail, while stronger governments like China will be the winners.”

Some prominent Westerners even see China’s rise as the product of a system that is in some respects superior. As two law professors recently argued in the Atlantic:

In the great debate of the past two decades about freedom versus control of the network, China was largely right and the United States was largely wrong. Significant monitoring and speech control are inevitable components of a mature and flourishing internet, and governments must play a large role in these practices to ensure that the internet is compatible with a society’s norms and values.

The New York Times’s journalist Thomas Friedman, meanwhile, embraces the Chinese notion of granting more power to credentialed “experts” for societal problems, arguing that they are too complex for elected representatives to address. The similarly minded economist Jeffrey Sachs denounces what he calls “an evangelical crusade” against the Chinese regime, pointing out that America’s own repressions disqualify any presumption of superiority.

Even some greens have rallied to China’s cause, which is faintly amazing given that the country produces more greenhouse gases than the US and EU together. Former California Governor Jerry Brown likes China’s top down approach and has embraced the notion of “brainwashing” as a necessary means of getting the masses to fall into line with the preferred emerging climate consensus. This Western admiration for Chinese authoritarianism is reminiscent of those who allowed themselves to be seduced by Stalinist propaganda in the 1930s, peddled by influential journalists such as the Times’ Pulitzer Prize-winning Walter Duranty.

A model for the “surveillance society”

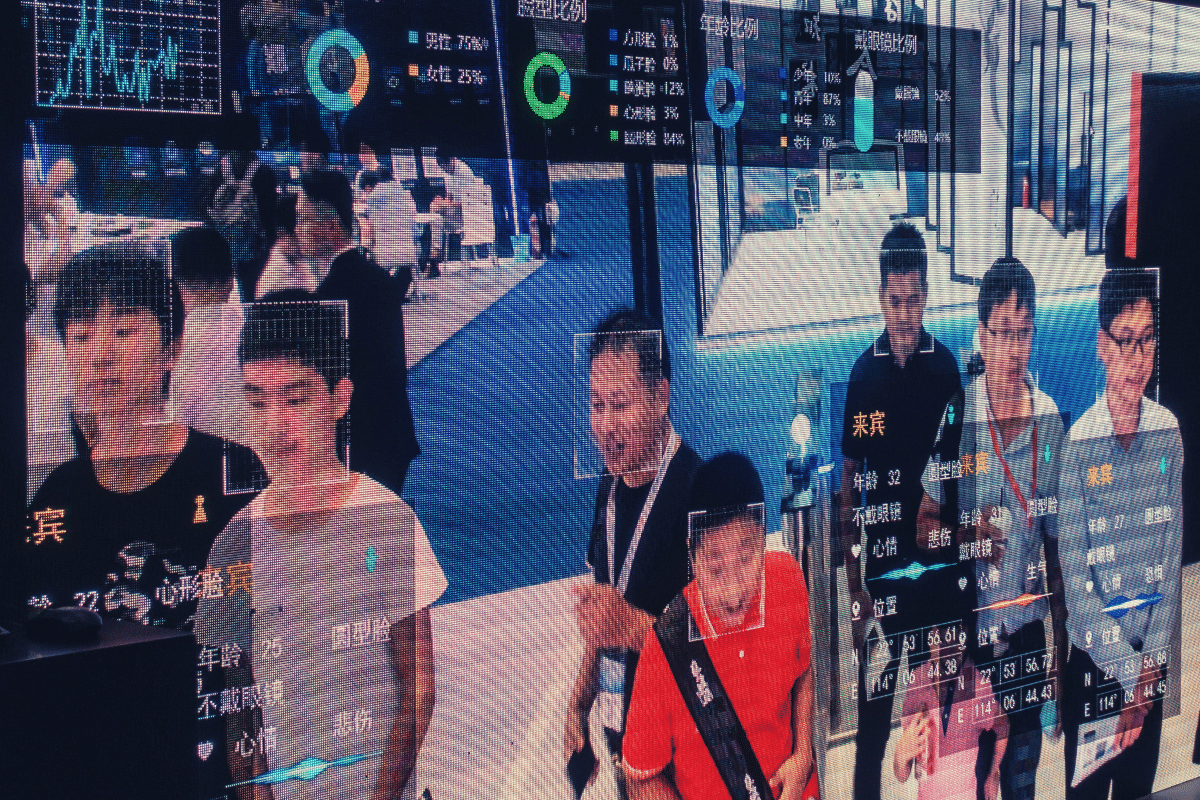

The British academic David Lyon writes about the emergence of “the surveillance society,” in which all individual activities are monitored from above. It is becoming, as one writer put it, “what Orwell feared.” In China, efforts to expand digital control have been boosted by US tech companies, including Apple and Google as well as Intel, Hewlett-Packard, and Western Digital. These companies have shown particular interest in China’s facial recognition systems, which is being used heavily in the Xinjiang region of western China, where Muslim Uighur dissidents are seen as a serious threat to the regime.

This is a place where simply wearing a beard, or giving your child a Muslim name, can draw the attention of the police. The facial recognition system allows authorities to follow someone on a watchlist; if they stray more than 300 meters from home or workplace, they could be arrested. The regime is also aiming to collect DNA from every resident of Xinjiang, and implementing a satellite tracking system for every vehicle in the region. “They are combining all of these things to create, essentially, a total police state,” said William Nee, a China campaigner at Amnesty International.

This “surveillance society” is not restricted to Xinjiang province. The regime plans to deploy over 400 million surveillance cameras in cities across the country by the end of the year. This surveillance is designed to regulate behavior, making it much more dangerous to express dissent, or even to commit a minor violation of traffic laws. The regime is also tracking smartphones and harvesting biometric data. Brain-reading technology seems destined to become more commonplace in Chinese factories, ostensibly to improve productivity, but also with a clear potential to monitor and manipulate the thoughts of workers.

This new reality permeates Chinese science fiction. In his short story “City of Silence” about the Internet in the near future, author Ma Boyong foresees attempts by “appropriate authorities” to restrict speech to “healthy words”; at the end of the book so few words are left that the “capital of the state” itself becomes mute. Ma’s story suggests an autocracy amplified by technology far more subtle than the Stalinist horror depicted by George Orwell. As one dissident in “City of Silence” suggests: “The author of 1984 predicted the progress of totalitarianism but could not predict the progress of technology.”

Some animals are more equal than others

Orwell’s insight about how Communism creates rigid hierarchies has proven particularly apt. Under its ostensibly “Marxist” regime, notes one observer, China is now developing “something resembling a permanent caste system.” In recent works of science fiction, China’s peasants and workers remain repressed, particularly in the countryside where many of the some 600 million rural Chinese still live in poverty. Liu Cixin’s “The Village Schoolteacher” describes a place “so poor that a bird wouldn’t shit on it.” Mao’s revolution may have been driven by the peasants, but President Xi’s “moderately prosperous society” may never reach them. The world Liu describes would not fit anyone’s vision of a desirable future society. The country already is becoming among the most unequal on the planet. In the future, they predict, class distinctions will become ever wider and more rigid.

Hao Jingfang’s “Folding Beijing” portrays a megacity divided into sharply delineated communities for the elite, the middle ranks, and a vast poor population living mainly by recycling the waste generated by the city. She depicts a city that changes shape into three forms—a luxurious first space with five million, a still comfortable second space accommodating 25 million and a third space, in which the protagonist Lao Dao lives where 50 million people cluster in stark conditions.

Similarly, Han Song’s clever “The Passengers and the Creation” speaks of a world that is contained within an airplane—with strict designations between first, second, and coach class. The velvet curtain that separates first class, Han writes, is “soft” but “as impenetrable as iron.” In this world, the wealthy aged live in comfort and can call on the services of young flight attendants recruited from coach.

Enforced conformity

Like Ma Jian’s protagonist in China Dream, the Chinese state’s goal is the assertion of control, by going as deep into private thoughts or behaviors as possible. Eighteen of the world’s 20 most heavily monitored cities are in China; Beijing and Shanghai already have a million each. The cult of conformity expresses itself as well in the banal uniformity imposed on China’s cities—endless rows of similar towers, shopping malls, glittering highways, and fast trains. In the process, the once distinctive terroirs of China’s great cities are being systematically eliminated. In urban China, old neighborhoods, with their histories, are being physically destroyed and residents uprooted to build physically imposing “global cities.” Maggie Shen King’s novel An Excess Male, set a few years in the future, has a longtime Beijing resident remembering the brutal razing of the old blocks of hutong, or courtyard houses, once common in the capital, and the displacement of residents:

Stately eight- and ten-lane boulevards crisscross the city and we rarely walk down one without… pointing out that countless properties were seized, and lives disrupted in the most egregious cases cut short to make possible their construction. Relegated to tiny stacked boxes, ordinary citizens pour into parks and scenic streets, thirsting for open air and elbowroom, so that our leaders could have their show of grandeur.

This search for control, notes Shen, who lives in the San Francisco area, extends to the details of private life. Her book describes a society in which women are allowed to take more than one husband, to encourage greater breeding and relieve social pressures. Shen’s heroine May-ling is married to two men, neither of whom is much interested in carnal relations and is looking to marry a third, an “excess male,” in order to have more children.

Following the demographic implosion created by the one-child policy, the government pursues and punishes anyone whose behavior, such as homosexuality, might impede the production of desperately needed children, something already much on the mind of Chinese planners and government officials. May-ling’s favorite husband, Hann, is gay. In the China of the future, people designated “willfully sterile” are persecuted for not procreating, losing their jobs and right to housing.

A warning from an imagined future

For the most part, journalists and political and business leaders are not likely to be dissuaded by the plainly nativist demagogy from President Trump and his most vehement right-wing allies. Nevertheless, science fiction writers reveal China’s fundamental weaknesses behind its facade of strength. To some extent, they express the angst of a millennial generation, which faces a troubling future and an aging society with diminishing opportunity. In Chen Qiufan’s Year of the Rat, a surplus college graduate ends up hunting genetically altered rats. “We are just like rats,” the protagonist suggests, “all of us only pawns, stones, worthless counters in the Great Game.”

Rather than the emergence of a China-dominated world order, as some in the West and many in Beijing propose, science fiction writers illuminate realities that could end up reprising the failures of the former Soviet Union. Ma Jian’s message, and that of Chinese science fiction, provides a cautionary tale for the 21st century. Sold as a dream, China’s future vision really constitutes a nightmare that we should seek to constrain and avoid.