Art

The Hagia Sophia Should Remain a Beacon to All

The Hagia Sophia was the brainchild of a unique figure in history.

On July 10th, Turkish President Recep Erdoğan undid the symbolic roots of his republic by declaring that the Hagia Sophia, a sixth-century Byzantine structure, would be converted from a museum to a mosque. The first Islamic service in the building is scheduled for July 24th.

The international response was a mix of shock, resignation, and near universal condemnation. Most official government statements were somewhere between the United States (“disappointed”) and Greece (an “open provocation to the civilized world”).

If the furor over a single museum strikes you as mystifying, consider the central role the Hagia Sophia has played for the last 1,500 years. Even from the beginning, it was far more than just a pile of brick and marble. It was a statement. A vision, both sacred and secular, for several different empires.

The Hagia Sophia was the brainchild of a unique figure in history. At birth, Justinian was a nobody among nobodies in a grindingly poor part of what is today North Macedonia. By his mid-40s, he was a Byzantine emperor. His appetites were large, his dreams larger. The man who knew what it was like to have nothing gave new meaning to the idea of luxury. For one memorable celebration, he spent almost two tons of gold on decorations.

Justinian had no time for small things. By the second year of his reign, he had decided to codify all of Roman law, founded several new cities, and had started construction on at least eight new churches.

The money for all these projects inevitably came from the public. And by the fifth year of his reign, his subjects had had enough. Already upset by rampant corruption, an inefficient bureaucracy, and crushing taxes, they hit the boiling point when Justinian severely restricted public games. A mob tore through the streets, overwhelming the unprepared police forces. Several stores were set on fire, and the wind quickly spread the flames to a nearby hospital, which burned down with its patients inside. An inferno raged. For five long days, Constantinople burned.

By the time Justinian reasserted control, more than 30,000 citizens were dead, and perhaps a third of the city was a blackened shell. It looked as if some barbarian horde had sacked the capital. The fact that its own people had inflicted such a wound hovered like a black cloud over the streets.

Characteristically, Justinian saw a perfect opportunity within the ashes. This was a blank canvas on which to create a new city in his image. The transformation would begin with the cathedral. The original building, known simply as the Magna Ecclesia—the Great Church—had been built by a son of Constantine the Great in the fourth century, but had burned down a few decades later. Since it was a standard Roman basilica—a large hall with square walls and angled wooden roof—it had been fairly easy to rebuild along the same lines.

But of course, Justinian had no intention of following the tired plans of an earlier age. This was a chance to remake the cathedral on a new scale, something worthy of the ages. It was to be nothing short of a revolution, equal parts art and architecture, the enduring grandeur of the emperor himself frozen in physical form.

Everything about this project was audacious, including his selection of architects. Instead of choosing a traditional builder, he picked two teachers who—like himself—had more vision than practical experience. This was a lifelong pattern with Justinian. He had a habit of plucking genius out of the common crush; his wife was a reformed prostitute, and his greatest generals were an elderly eunuch and a former bodyguard.

The emperor’s instructions to Isidore of Miletus, a physics teacher, and Anthemius of Tralles, a mathematician, should have terrified them. They merely had to design and successfully build a church unlike anything else the world had seen. Sheer scale wasn’t enough—the empire was full of grand monuments and immense sculpture. This had to be something different, something fitting for the new golden age that was dawning. Expense wasn’t an issue, but speed was. Justinian was already in his 50s, and he didn’t intend to have some successor apply the final coat of paint and claim the project as his own.

This last bit was surely impossible. The large wonders built with the technology of the early sixth century could take lifetimes to construct. Medieval Notre Dame would take more than a hundred years to build, and the Duomo in Florence more than twice that.

Justinian’s architects came up with an audacious plan. Rejecting the classical basilica form that had been in use for three centuries, they decided instead to build the largest unsupported dome in the world and put it on a square floor plan. No architect had ever tried this before, for the excellent reason that a circular dome on a square base would either collapse in on itself or push the walls over. To prevent this, they ingeniously distributed the immense weight over a cascading series of half-domes and cupolas.

The Roman emperor stood halfway to heaven, so heaven and Earth were moved. The riches of the Mediterranean world were poured into the construction. Each day, new marvels appeared from a different corner of the empire. Gold from Egypt, delicately textured marble from Asia, and precious stones from north Africa. Antiquity served as a quarry: Even the fabled Temple of Artemis, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world, donated a column.

To speed up construction, Isidore and Anthemius split their crew into two groups and raced them against each other. Spurred on by the presence of the emperor’s daily site visits, the two teams worked at breakneck speed. Five years, 10 months, and four days from the laying of the first stone, the great work was done.

On December 27th, 537, the church was officially dedicated as Hagia Sophia—the Divine Wisdom, an allusion to Christ. Stepping through the great imperial doors into the vast interior for the first time, Justinian was overwhelmed, struck by a vision of heaven made real in every graceful curve and sweeping arch. The cavernous dome rose 18 stories above the ground, spacious enough for the Statue of Liberty to fit inside, with six feet to spare between the tip of her torch and the ceiling. Around its base, builders had placed windows lined with gold. As light flooded into the building, the dome itself would appear to hover on a sea of light, suspended, as one stupefied observer wrote, “as if from heaven on a golden chain.”

The nearly four acres of ceiling space were covered with glittering mosaics, and a massive 50-foot iconostasis of solid silver was hung at the front, engraved with images of Mary, Jesus, and the saints. Beyond lay the high altar, sheltering an unrivaled collection of relics, from the hammer and nails of the Passion to the swaddling clothes of Christ. Even the wood above the great imperial door was unlike any in the world—composed, it was said, from an ancient fragment of Noah’s Ark. After Justinian had taken a long moment to observe all this, those closest heard him whisper, “Solomon, I have surpassed you.”

There was no building like it in the world, nor would there be for a thousand years, until Florentine architect Filippo Brunelleschi built his Duomo with a larger dome. Few could enter such a space and remain unmoved. When a visiting Russian delegation heard a mass inside the cathedral, members famously wrote back to their monarch, “We knew not whether we were in heaven or on earth.”

It was easier to believe it was heaven. The monarch converted and the Russian Orthodox church was born.

The Hagia Sophia was the heart of Byzantium. From the time of its construction, there was hardly a major event in the millennium-long history of the Eastern Roman Empire that wasn’t in some way connected to it. Every Byzantine emperor—with the notable exception of the last—was crowned at its high altar. To have the cathedral was to have Constantinople and its empire. To lose it was to lose everything.

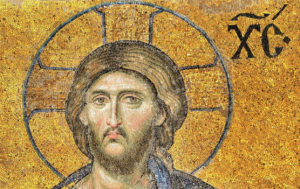

Even when Byzantium was dying, the Hagia Sophia remained a beacon. Inside was a treasure trove of art assembled through nine centuries of imperial patronage. Its mosaics—most famously the Deesis in one of the upper galleries—anticipated the humanism of the Renaissance by more than a century. Crusaders stared in awe, barbarians gawked, and civilized rulers tried to copy it. Its domed shape was echoed a thousand times in miniature throughout the Christian and Islamic worlds. Countless mosques and churches still bear its reflected form.

In 1453, the long pageant of the Eastern Roman Empire came to an end. The Ottoman sultan Mehmet the Conqueror earned his nickname by taking the city by storm. The Hagia Sophia, sheltering many of the city’s terrified citizens, suffered the fate of all of Constantinople’s churches. It was thoroughly plundered; crosses were demolished or replaced by crescents, altars and icons were destroyed and those who had taken refuge inside were killed or enslaved.

Mehmet didn’t just want to destroy, however. He wanted to build. Islam had triumphed over Christianity and a new world order had dawned. He personally oversaw the conversion of the Hagia Sophia, announcing a sea change in history. The crowning jewel of Christendom became the great imperial mosque of the Muslim world.

It remained so for nearly 500 years. At its height, Ottoman power surged through the Balkans and reached the walls of Vienna. It seemed as if all of Europe might fall. But Vienna held. And by the 17th century, the Ottomans entered a long, slow decline. The once proud Muslim state became the “Sick Man of Europe,” propped up by stronger Christian, European nations.

The centuries of impotence and humiliation culminated in the complete collapse of the Ottoman empire in the 1920s. Under the leadership of a charismatic nationalist named Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the Caliphate was abolished and a republic was founded on a Western, secular model. Atatürk’s modern state was an explicit rejection of the Islamic theocratic system, and he needed a powerful symbol to drive this point home. Once again, the Hagia Sophia was pressed into service. In 1931, Islamic services were stopped. Three years later, it officially opened as a museum. A quintessential icon of the militant, Islamic past was now a symbol of modern Turkey.

Now, 86 years later, the tide has turned again. Atatürk’s secular legacy must be discarded, so Erdoğan turns to the Hagia Sophia.

The great masterpiece of the Byzantine world, built on a fault line, yet still standing after nearly 15 centuries, casts a long shadow. There are 30 major churches named after it in more than a dozen countries. It was always the dome—still so visible on Istanbul’s skyline—that most inspired observers, going all the way back to Justinian’s contemporaries. As Garo Paylan, a member of Turkey’s parliament, put it succinctly, “The Hagia Sophia was a symbol of our rich history. Its dome was big enough for all.” How regrettable that such a vast space would be co-opted for narrow ends.