Memoir

Remembering My Friend Peter Beard

Peter is no longer here to tell us the truth of the matter.

Peter Beard, internationally renowned photographer, author, railroad-fortune heir, and socialite, died last month. Or possibly in March. Beard (b. 1938) had been ill, and suffering from dementia. He wandered off into the forest near his home on Long Island. He was 82.

His body was found in a nearby national park, which is grimly fitting, for wildlife and parks were some of his abiding passions. The unconventional manner of his death also matched the way he lived. And if he were going to pick a way to go out, this might have been it.

Having gotten to know him reasonably well when we both lived in Kenya, I suspect he would have preferred not to have been found, however, as he was a consummate trickster. He might well have preferred an obit that said, “Mr. Beard disappeared from his home in Montauk sometime in the spring of 2020. His whereabouts are unknown.”

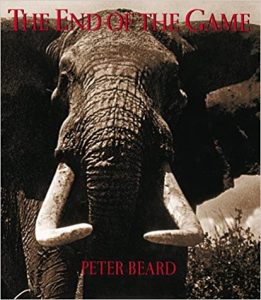

Peter was a gifted photographer, an engaging diarist, a gracious and generous host, a non-stop raconteur, universally described (truthfully) with that cliché, “one of a kind.” His first book of photographs, The End of the Game, consists largely of portraits of dead elephants, a project he pursued in Tsavo National Park during the height of the post-independence poaching frenzy in the early 1960s. Had it continued unabated, it could have meant the end for wild elephants in all of Kenya and perhaps even Tanzania. The photos are aesthetically arresting, graphic, and perversely fascinating, as he managed to evoke the dignity and beauty of the elephant literally in its death throes. The book has a pagan feel to it.

Then there is his phenomenally quirky and engaging Longing For Darkness: Kamante’s Tales from Out of Africa. Beard had been a friend of Out of Africa author Karen Blixen (1885 – 1962), and managed to track down her cook, Kamante, after Blixen’s death. Beard interviewed him, transcribed the interviews, and published an illustrated counter-narrative to Out of Africa—an Out of Africa “from the ground up,” so to speak. Then there is his surreal collection of photos and jottings, Eyelids of Morning, documenting his exploration of Lake Turkana, its traditional peoples and enormous crocodiles. It is my favorite book of his, as I lived and worked in that part of Kenya for five years and got to know the area well.

I once went swimming in Lake Turkana. I spent two hours luxuriating on a beach and in waters that reminded me of the Edgar Rice Burroughs adventure series Carter of Mars. There was no sign of civilization anywhere. I was oblivious to the man-eating crocodiles because I’d asked some local Turkana tribesmen earlier in the day if it was safe to swim and they’d assured me it was, learning only later that they were apparently quite mistaken. This gave me a taste of the kind of stimulation that Peter originally searched for in Africa. (Although I lived near the shores of Lake Turkana for years, I never swam there again.)

Peter’s parents were multi millionaires on both sides—Anglo-American “old money.” By the time he went to Yale to study art history, he’d been obsessively taking pictures and curating his diaries since age 12. His central passion was African wildlife, but he was also a fashion photographer. He photographed, dated, and caroused with some of the era’s first “supermodels,” and even briefly married one, Cheryl Tiegs.

Although born in 1938, Peter was a classic child of the 60s, and fell in with famous pop stars. He would regale me with stories of partying with Mick Jagger and the Rolling Stones, and with David Bowie (who married his fashion-model discovery Iman, a Kenyan citizen of Somali ethnicity). He talked a lot about his editor, a woman named Jackie Kennedy.

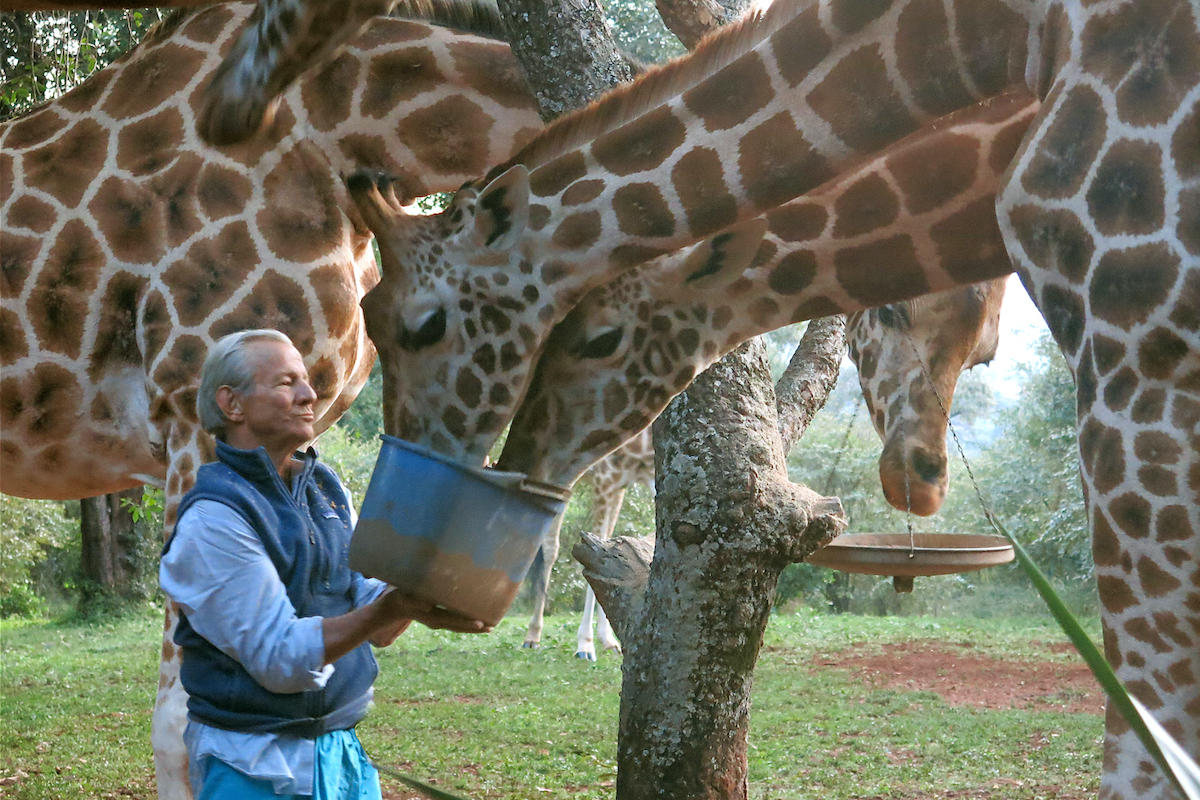

My wife Mira often came with me to visit him at his camp, Hog Ranch, on the edge of what used to be his mentor Karen Blixen’s estate. I have a strong memory of the one time when we discussed the worst film we’d seen on Kenya, Nairobi Affair (sometimes marketed simply as Nairobi), starring Charlton Heston. It was one of those films that we both agreed was so bad it was good, and we talked about screening it locally. Mira pointed out that Peter himself could have been a supermodel, as he was blessed with unnaturally good looks.

Peter was mildly intrigued to learn that I’d carried out research on the music of the tribes around Lake Turkana. I once told him about the poetry of Rendille prayers, a group of camel-tending nomads whom I’d lived among east of the lake, near Marsabit. (Much of my research in Africa has been in the area of ethnomusicology.) On one visit to Hog Ranch, I recited them, in Rendille and in English translation. He saw the poetry in them and remained intrigued. One thing Peter could not talk about was classical music. Unlike Blixen, he found it did not speak to him.

We visited Hog Ranch many times. Peter would often offer us beer or whiskey, and ask if we wanted to share some marijuana with him. He was never offended when we said no.

Back in the early 1990s, I had a cover band that played the night spots of Nairobi. It was made up of me (as guitarist and singer), a Canadian keyboardist whose day job was doctor, a white Kenyan lead singer and school headmaster, a Scottish bassist, an Irish drummer, and a female Kenyan Rendille singer who’d been raised in Germany and was told she looked like Tina Turner. We were a motley crew and called ourselves Foreign Affairs. Peter would often drop by the Carnivore restaurant (yes, zebra and crocodile were on the menu) to hear us play his favorite rock hits. He told me that we “sounded all right.” I thought this wasn’t a bad compliment coming from a guy who regularly hung out with Keith Richards.

On one occasion, Peter came across a collection of objects that he believed were bones that had been carved, sculpted, and used by the Okiek or Maasai shamans (known as laibons) to tell the future. He was told that the old ways were dying, and that the Okiek now did not mind selling these artifacts that so appealed to Western buyers. At the time, I was the head of the Department of Ethnography at the National Museums of Kenya, and Peter wanted me to authenticate the collection. I told him I had to give this some thought, after which I managed to speak about the issue with Kenyan palaeoanthropologist and conservationist Richard Leakey, who dismissed the collection as fake from the outset and believed Peter was staging a publicity stunt. But I decided to give Peter the benefit of the doubt.

Meanwhile, Roderick Blackburn, a fellow anthropologist who’d also been friends with Peter for some time, began making his own inquiries among the Okiek, cataloguing the collection and showing it to elders to see if they knew what these objects were or had been. (Rod had done his fieldwork among these hunter gatherers of the highland Mau forest, who’d maintained a symbiotic relationship with the plains-dwelling Maasai cattle herders who lived below them.) I realized that to do justice to this “unprovenanced” collection, we’d need a team of experts. I wrote up a proposed team that would include a chemist, an archaeologist, an expert on the Maasai, and a museologist whom I suggested we bring to Kenya from England and who was an expert in evaluating forgeries. I dropped it off at Peter’s, and he said he would read it over.

A couple of weeks later, he welcomed us back to Hog Ranch. Over beer and potato chips, he lamented that he was “broke.” He liked the proposal, but did not have the money to pay the consultants. This was coming from a guy whose family was worth scores of millions of dollars. Just as I was about to leave, he said, “Hold on, I have something for you.” He then gave me a black and white photographic print of his daughter Zara leaning against a domesticated African warthog, the mascot of Hog Ranch. I have it filed away somewhere.

When we left, he repeated his mantra about the objects with his characteristic boyish charm and enthusiasm. “Geoffrey, you have seen them,” he said. “You have felt them. They are just like Brâncuși sculptures.” Then, at the height of his enthusiasm, he asked, “Can’t you just feel it?!”

Later that month, I had dinner with Monty Reuben, a businessman who’d been born and raised in Kenya. He knew Peter well, and said that he’d often overdrawn from his family’s fortune. (Hog Ranch, I should note, was really just a bunch of tents and a cabin, which he used as his studio.) I certainly did not have the time or money to do the research for free, curious as I was to get to the bottom of this anthropological mystery.

Some of my colleagues told me that they thought Peter wanted me to authenticate the collection so that he could sell it for half a million dollars at Sotheby’s in New York. It may have been true, and then again maybe not.

Some time later, in 1992, Peter published a book of photos, The Art Of The Maasai: 300 Newly Discovered Objects and Works of Art. It’s a thing of great beauty. Yet to this day, we still do not know if the collection at the heart of it is real or fake‚ or whether these were real objects that had been doctored. One of the things that puzzled me is that almost all of the objects had straight bottoms, as if they’d been altered to stand on a table or in an exhibit box at a place like the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan.

Peter is no longer here to tell us the truth of the matter. They say he kept a daily diary, though I did not know it at the time. Perhaps he made a note of my visits. Perhaps he kept a copy of my proposal in his files to contrast my own fussy, bureaucratic style with his marvellously free-associative travel-writing style. I sincerely doubt it, but if that is indeed the case, I will not protest playing some marginal foil’s role in a fine artist’s oeuvre.