Art and Culture

The First Stone

Philip Schofield and his critics could both learn a lot from Oscar Wilde’s prison memoir.

Pride goes before destruction, and a haughty spirit before a fall.

~Proverbs 16:18

When The Importance of Being Earnest premiered at the St James Theatre in London in February 1895, its intoxicating success brought Oscar Wilde to the zenith of his brilliant career. He was celebrated for his glazed wit, flattered by the critics, and fawned over by the ambitious. Every fashionable drawing room of the beau monde was open to him. A little more than three months later, he would lose it all and find himself reduced to a despised and penniless social pariah. Days after his play opened, the Marquess of Queensberry, the father of Wilde’s lover, the charming but feckless Lord Alfred “Bosie” Douglas, accused Wilde of being (in the Marquess’s spelling) a “somdomite.”

Against the advice of his friends, Wilde rashly brought a private prosecution against Queensberry for libel. He lost. Queensberry was awarded costs, which bankrupted Wilde, who was not flush in the first place; the lavish lifestyle he enjoyed with Bosie churned through money as quickly as it came in. Almost immediately upon the close of the libel trial, Wilde was arrested and charged with gross indecency. The jury could not agree on a verdict at the first trial, but he was convicted in a second, following sensational evidence of his sexual tastes from assorted rent boys, blackmailers, and others. Wilde was sentenced to two years of hard labour. After his release, persona non grata to respectable society, Wilde fled to France where he died in poverty and obscurity in 1900, attended only by a small residue of faithful friends. He was just 46.

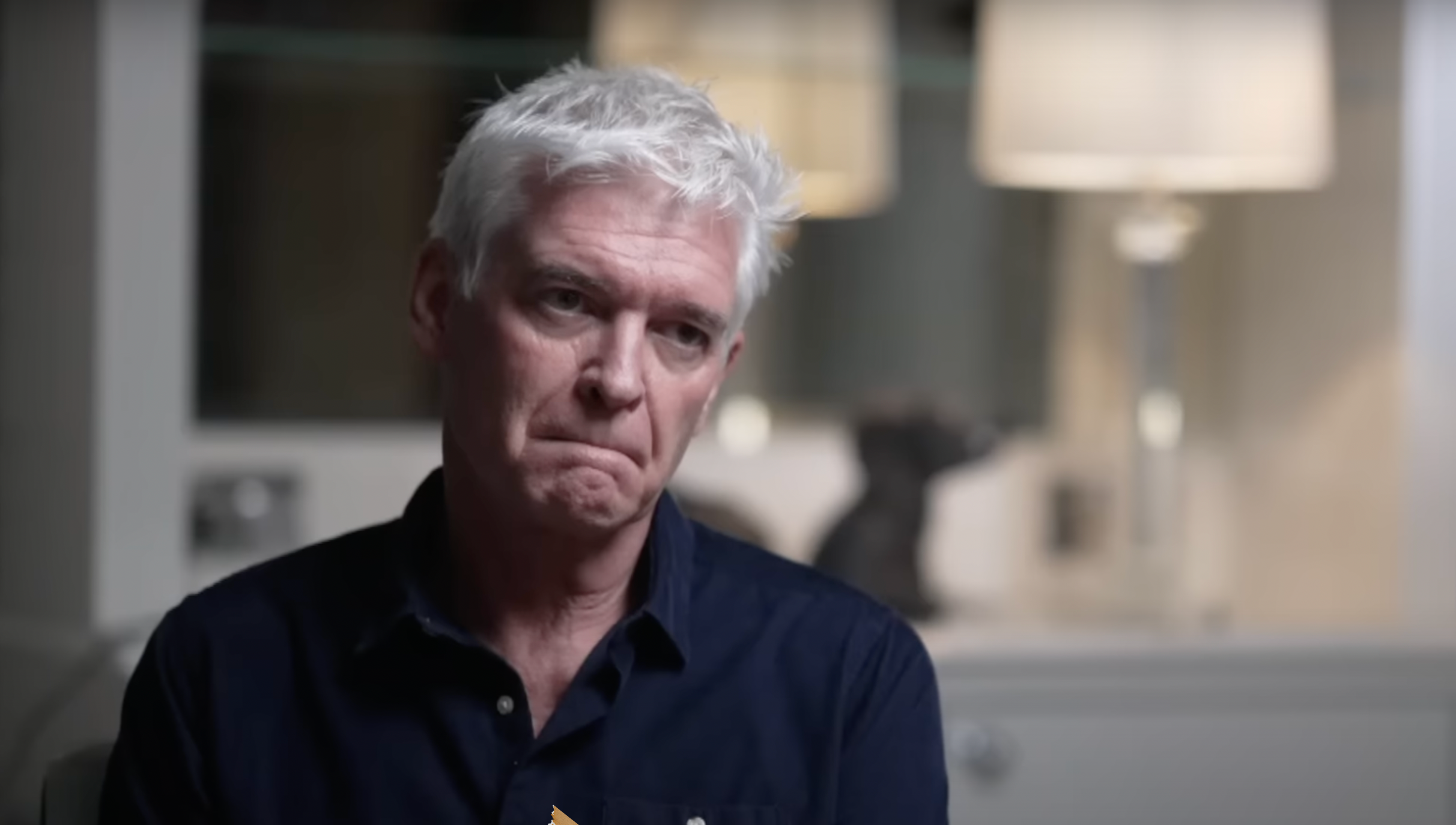

Readers will certainly have heard of Oscar Wilde, but those outside the UK will probably not have heard of Philip Schofield. A month ago, Schofield was one of Britain’s most prestigious television personalities. He hosted This Morning, an award-winning late-morning talk show, on ITV for 20 years, the last 14 of which he co-presented with Holly Willoughby. In 2020, Schofield came out as gay and separated from his wife (to whom he remains married). In late May, following a long period of gossip, Schofield resigned from ITV, admitting that he had lied to the company, his colleagues, his family, his agent, his lawyer, and the media to conceal a sexual relationship with a much younger male colleague in a more junior position. Schofield described the relationship as “unwise but not illegal.” It has since emerged that the two first met years earlier, when the young man was 15 and that Schofield helped get him a job at ITV. These facts have attracted accusations of grooming which Schofield strongly denies.

Now why on Earth am I linking Oscar Wilde and Philip Schofield? Two reasons, one a fact, the other an opportunity.

The fact

The sad fact is that both men suffered—and Schofield is still suffering—cruel public shaming. In Wilde’s case, friends and associates abandoned him, polite society expelled him, the law incarcerated him, and his wife—though she sent him money—refused to see him or to let him see his children in his final years. He became a figure of public scorn. In De Profundis, the great work of self-examination he wrote from prison, Wilde recalled the crowd that taunted him on the platform of Clapham Junction railway station as he was being transferred from Wandsworth Prison to Reading Gaol:

On November 13th, 1895, I was brought down here from London. From two o’clock till half-past two on that day I had to stand on the centre platform of Clapham Junction in convict dress, and handcuffed, for the world to look at. I had been taken out of the hospital ward without a moment’s notice being given to me. Of all possible objects I was the most grotesque. When people saw me they laughed. Each train as it came up swelled the audience. Nothing could exceed their amusement. That was, of course, before they knew who I was. As soon as they had been informed they laughed still more. For half an hour I stood there in the grey November rain surrounded by a jeering mob.

For a year after that was done to me I wept every day at the same hour and for the same space of time.

Philip Schofield would, I think, understand. Since the scandal over his affair broke, he has had to endure relentless criticism before an audience much amplified by modern technology since Wilde’s time. And by “relentless,” I mean that the fusillade has been daily, almost hourly. I am not thinking so much of the anonymous demons of social media, but rather of his industry peers and rivals, some of whom seem to be taking great pleasure in his downfall, grasping their moment for the limelight or revenge, and crossing the line from responsible commentary into malicious denigration. Former ITV colleagues and guests have appeared on rival channels describing Schofield—and Willoughby—as “phony and fake,” “as false as they come,” and “narcissists” with “ridiculously obnoxious” egos.

Schofield’s former close colleague Eamonn Holmes found it necessary to tell viewers of his GB News show six times that Schofield “lies, lies, lies, lies, lies, lies,” and that he was the “chief narcissist” in a workplace that he described as a “den of iniquity.” Some have insinuated, without evidence, that further concealed relationships may yet emerge. They have been even crueller about Holly Willoughby. One talking head called her “the fakest person I’ve met in TV” (quite a prize in a crowded field), while another called her a “two-faced horror” and a “little bitch.”

My point is not that Schofield should be treated leniently or even that the harsh evaluations of his character are untrue. Public figures, even those in light entertainment, need to be held accountable and often that is not going to be a pretty sight. Journalists and commentators are right to ask questions about potential conflicts of interest and whether or not ITV covered up (to use the now-universal cliché) “a toxic workplace” for years. My complaint is that the tone of this criticism has been needlessly febrile, gloating, and lurid, and motivated as much by the need to keep an entertainment circus going as to serve any genuine public interest.

One may also point out the hypocrisy of much of the criticism. The always insightful Kathleen Stock trod a fine line, but managed to stay on the right side of it, I think, when she frankly described Schofield and Willoughby and the Good Morning program as “pathologically bland, pathologically nice: everything dark is just pushed away and it is this sunshine studio.” But as I am sure she realises, that illusion of concord and affection—the personnel on such programs are always a “family”—is hardly confined to ITV or its Good Morning show. It characterises a lot of television, especially light entertainment and the celebrity merry-go-round culture of which it is part. Because it chases ratings and grooms egos, and panders to popular public taste, television often contains an element of falsity, the presence of which is less a pathology and more its normal condition.

Then, inevitably, as Stock says, “the mask slips and you see all this humanity and mess behind it, and people cannot stop looking at that.” The spell is briefly shattered and there is a sudden lurch from insipid congeniality to feeding frenzy. As Wilde observed in his own case:

Well, now I am really beginning to feel more regret for the people who laughed than for myself. Of course when they saw me I was not on my pedestal, I was in the pillory. But it is a very unimaginative nature that only cares for people on their pedestals. A pedestal may be a very unreal thing. A pillory is a terrific reality. They should have known also how to interpret sorrow better. I have said that behind sorrow there is always sorrow. It were wiser still to say that behind sorrow there is always a soul. And to mock at a soul in pain is a dreadful thing. In the strangely simple economy of the world people only get what they give, and to those who have not enough imagination to penetrate the mere outward of things, and feel pity, what pity can be given save that of scorn?

The vehemence of the scorn directed at Schofield is perhaps partly due to the fact that he has exposed not just himself but a whole industry. He has pulled back the curtain to reveal the machinery that creates the illusion, and that sin is unforgivable. “To mock a soul is a dreadful thing” because it denies all possibility of forgiveness. At the beginning of this month, as the media storm raged above him, Schofield gave an interview to the BBC in which he said this:

I’ve actually brought myself down to a far, far greater degree than you could ever have done. I have brought myself down. I am done. I have to talk about television in the past tense which breaks my heart. But it continues and it is relentless and it is day after day and day after day. And if you do that, if you don’t think that is going to have the most catastrophic effect on someone’s mind[.] ... Do you want me to die? Because that’s where I am. I have lost everything.

When this is simply dismissed as more lies, Schofield’s critics display the very poverty of imagination of which Wilde wrote—a nature that craves the pedestal, envies success, and for the fallen knows pity only as contempt. The sanctimony of such voices is merely the simulacrum of a call to repentance. It knows no mercy and seeks only to wound. Contrast this act of kindness reported by Wilde:

Where there is Sorrow there is holy ground. ... When I was brought down from my prison to the Court of Bankruptcy between two policemen, Robbie [Ross, a close friend of Wilde’s] waited in the long dreary corridor, that before the whole crowd, whom an action so sweet and simple hushed into silence, he might gravely raise his hat to me, as handcuffed and with bowed head, I passed him by. Men have gone to heaven for smaller things than that.

Wilde also recorded the kindness of strangers: the warder who would bid him a “good morning” or a “goodnight” not prescribed in his duties, the policemen who struggled to comfort him in his distress before the mocking public crowds, and the “poor thief” who approached him in the yard at Wandsworth prison to hoarsely whisper, “I am sorry for you: it is harder for the likes of you than it is for the likes of us.” Of these men, he told Bosie Douglas, there is not one the “very mire from whose shoes you should not be proud to be allowed to kneel down and clean.”

The command of gratitude. That is what such acts of kindness—small tokens of human sympathy and solidarity, even those that from a practical point of view are mere gestures—can mean to those who suffer, especially those who suffer social banishment. When the conscience of a man who has fallen by his own doing is reaching awareness of his faults—as seems to be the case with Philip Schofield—kindness encourages truthfulness and remorse. It is a handrail to contrition and reform, the acknowledgment of a shared frailty that is the common human lot. By contrast, self-righteous malice provokes defiance and resentment, which can only bear rotten fruit.

The opportunity

Though he will find it hard to acknowledge this now, it is possible that Schofield, rather than his tormentors, is the fortunate one in the current drama. It is said, often too thoughtlessly, that suffering makes us better or at least wiser. That may sometimes be true, but just as often it is not. Wilde wrote that prison does not tend to make a man humble; its “endless privations and restrictions” make men rebellious. If any suffering does endow wisdom I suspect it is due to humiliation—not in the sense of degradation, but in the sense of suffering a rebuke to one’s pride. This is why the wisdom of humility can come to those who have fallen from great heights on account of their own foolishness. That foolishness affords an opportunity that can be grasped. O Felix Culpa!

De Profundis, though marred by Wilde’s bitter recriminations against Bosie Douglas, is nevertheless a record of a man’s spiritual awakening to his own pride and infirmity. He wrote:

I have lain in prison for nearly two years. Out of my nature has come wild despair; an abandonment to grief that was piteous even to look at; terrible and impotent rage; bitterness and scorn; anguish that wept aloud; misery that could find no voice; sorrow that was dumb. I have passed through every possible mood of suffering. Better than Wordsworth himself I know what Wordsworth meant when he said:

Suffering is permanent, obscure, and dark

And has the nature of infinity.

But while there were times when I rejoiced in the idea that my sufferings were to be endless, I could not bear them to be without meaning. Now I find hidden somewhere away in my nature something that tells me that nothing in the whole world is meaningless, and suffering least of all. That something hidden away in my nature, like a treasure in a field, is Humility.

It is the last thing left in me, and the best: the ultimate discovery at which I have arrived, the starting-point for a fresh development. It has come to me right out of myself, so I know that it has come at the proper time. It could not have come before, nor later. Had any one told me of it, I would have rejected it. Had it been brought to me, I would have refused it. As I found it, I want to keep it. I must do so. It is the one thing that has in it the elements of life, of a new life, Vita Nuova for me. Of all things it is the strangest. One cannot acquire it, except by surrendering everything that one has. It is only when one has lost all things, that one knows that one possesses it.

Humility is indeed worth more than all the power and fame in the world. One does not have to lose all things, or even necessarily have to forsake all power and fame, but one does need to forsake the craving for them. The punitive and unforgiving atmosphere that pervades not only the world of celebrity but, strikingly, the “culture wars” of our politics, is a way of clinging to that craving and the result is that humility is a scarce resource. The opportunity to acquire it is not to be passed up.

The reader may still find it odd that I have linked Oscar Wilde and Philip Schofield. They are, after all, very different. Wilde was a prodigy, Schofield is likely a man of average talents. Their shared sexuality is irrelevant. Wilde was punished under a barbarous law, while Schofield stands accused of exploiting a vulnerable youngster in a subordinate role and lying to cover it up. But these differences are beside the point. What Wilde repented, and Schofield hopefully does too, was reckless vainglory, the sense of immunity and entitlement to worldly spoils—what Wilde called shallowness, the “supreme vice.” And they are not alone. They are Oedipus. They are St Peter before the cock crowed. They are Everyman. And each of us may, without presumption, claim to stand in the place of the adulteress, in whose defence these words were spoken: Let he who is without sin cast the first stone.