Top Stories

As Common Sense Returns to the Gender Debate, Radicals Set Upon Their Own Allies

The entire argument was about whether one particular trans ally had become too famous at the expense of more worthy and authentic competitors.

In 2014, Ottawa-based writer Amanda Jetté Knox reported that her child Alexis had “come out to the family as a transgender girl.” This event changed Knox’s life, as “Alexis’ journey taught [her] a great deal about courage, compassion and authenticity.”

A few months after that, Knox’s spouse came out as transgender as well. Knox reported to her readers that this realization, too, was “beautiful,” and that she could not be more delighted to now be “gay married.”

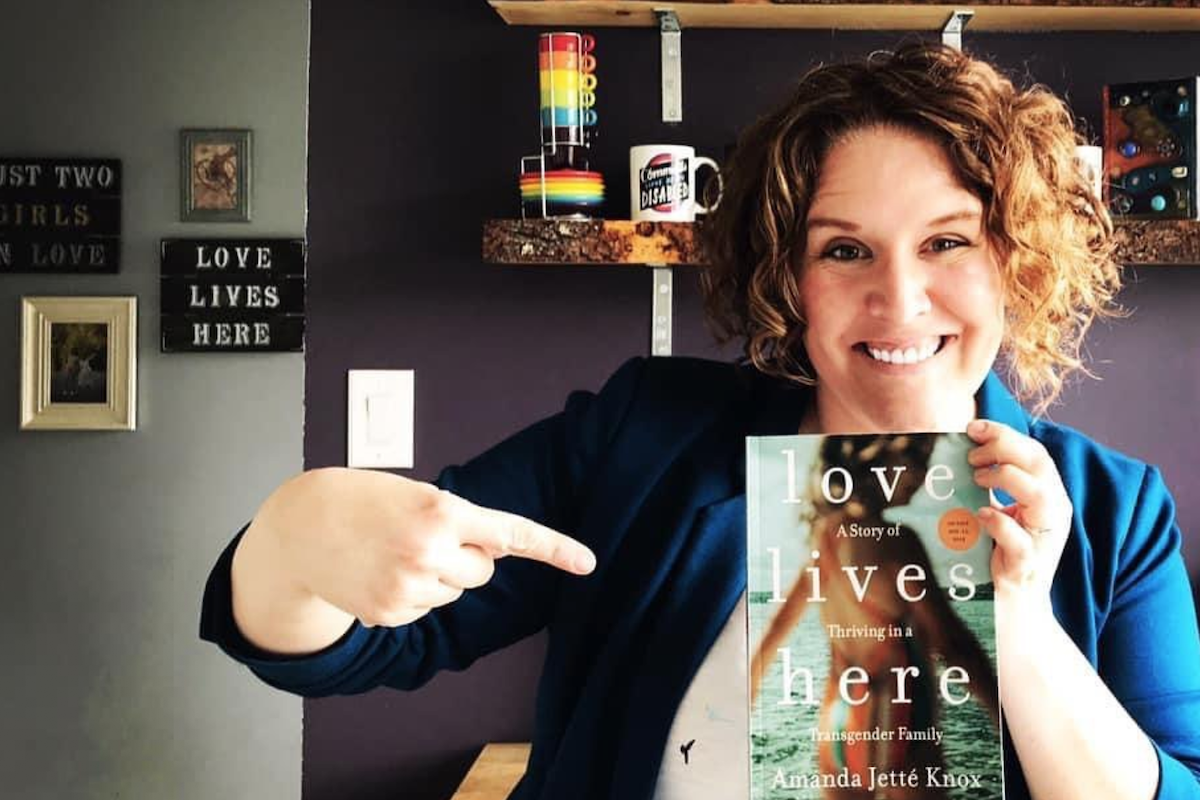

In blog posts, Knox described the whole family as “the happiest we’ve ever been,” and wrote that “our world is so full of love and support that it leaves absolutely no room for hatred or ignorance to reside within it.” Indeed, Knox made gender transition her professional focus, “studying research, interviewing experts, giving talks, writing articles” about trans issues. She authored a bestselling 2019 book about her experiences. In newspapers and magazines, she wrote articles under headlines like “The only way to respond to my transgender child’s desperate plea was with love,” “My daughter came out as trans, and it saved my marriage,” and “My wife surprised her coworkers when she came out as trans.” Knox gushed on CBC radio, took the stage at a Microsoft-sponsored event in Vancouver, and appeared on numerous television programs, always relentlessly promoting the same upbeat message of how trans-inclusiveness had brought joy to her household, over which there is now “a permanent rainbow… that unicorns like to prance around on.”