Environment

Capitalism or the Climate?

Technological knowledge, fueled by capital, has allowed us to do many things categorically unlike the achievements of other species as far as we know.

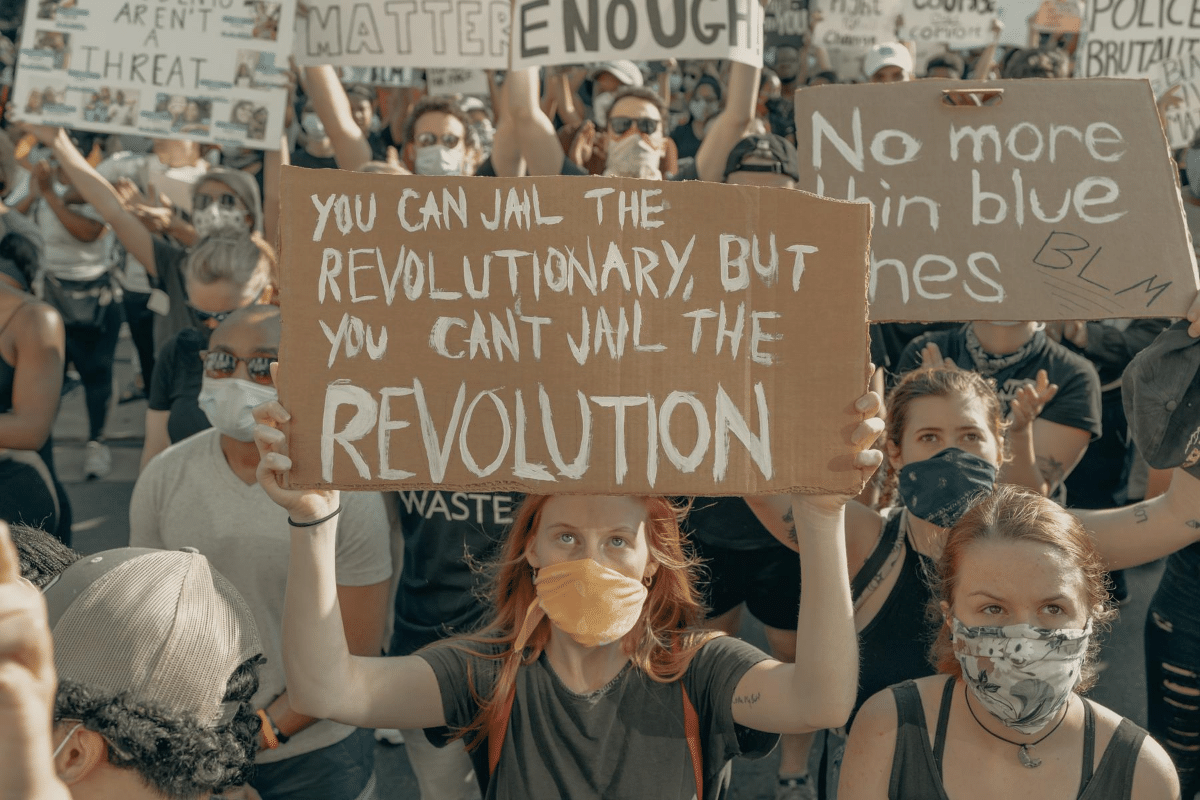

Can environmentalism and capitalism sustainably coexist? An influential movement of climate activists view capitalism and environmentalism as antithetical. According to the title of an article in the Guardian, “Ending Climate Change Requires the End of Capitalism.” An article in Foreign Policy, meanwhile, is subtitled, “New data proves you can support capitalism or the environment—but it’s hard to do both.” And in her bestselling book This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate, Naomi Klein writes, “By posing climate change as a battle between capitalism and the planet, I am not saying anything that we don’t already know.” These are just a few of countless prominent examples.

This view dwells not just in newsrooms, but in the halls of government as well. US Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, author of the 2019 Green New Deal resolution and surrogate to Bernie Sanders in the 2020 democratic primary, told a 2019 SXSW audience, “Capitalism, to me, is an ideology of capital. The most important thing is the concentration of capital, and it means that we seek and prioritize profit and the accumulation of money above all else, and we seek it at any human and environmental cost. That is what that means. And to me, that ideology is not sustainable and cannot be redeemed.” Similar implications can often be gleaned from the utterances of Senator Sanders himself:

By contrast, moderate environmentalists, such as the Nobel Prize-winning economist William Nordhaus in his book The Climate Casino, argue that geoengineering paired with modest carbon taxation or cap and trade policies could sufficiently mitigate climate change without severely debilitating economic growth. But whether you think a radical view or a moderate view is more realistic, it is worth asking the question: What should we do if environmentalism and capitalism are truly incompatible?

It is often taken for granted that if we can have only one, we should scrap capitalism and sustain the climate. “What the climate needs to avoid collapse,” Naomi Klein has written, “is a contraction in humanity’s use of resources; what our economic model demands to avoid collapse is unfettered expansion. Only one of these sets of rules can be changed, and it’s not the laws of nature.” This common perspective results from widespread misconceptions, and overturning them will show that capitalism is more critical to humanity’s future than environmentalism.

The myth of Spaceship Earth

Almost everyone believes the Spaceship Earth misconception, even if they don’t have a name for it. I was a believer myself until I read The Beginning of Infinity by David Deutsch, physicist at the University of Oxford. Spaceship Earth is the notion of our planet as a lifegiving oasis in a mostly desolate universe. According to this notion, the Earth provides us all the resources necessary to sustain human life, and it is up to us to either live sustainably or destroy the cornucopian vessel upon which we depend.

What is wrong with the Spaceship Earth concept? In short, Earth is mostly not capable of sustaining life. Roughly 99.9 percent of all species that have ever existed on Earth are now extinct, some due to mass extinction eventsand some in so-called “background extinctions.” So in reality, the Earth is almost entirely inhospitable. By contrast, an estimated 3.15 percent of US executions between 1890 and 2010 failed to kill their victims. A species on Earth has a better chance of becoming extinct than a person has of being put to death efficiently in an electric chair.

Deutsch points out that if he were suddenly transported to the Great Rift Valley in its primeval state, he would probably die in a matter of hours. Likewise, most Amazonian populations throughout history would have quickly died in the Arctic, and most Arctic populations would have died in the Amazon. Very few of us would survive for long if suddenly transported to a random place and time on Earth.

Knowledge, Deutsch argues, is the variable most relevant to our potential flourishing. When Arctic populations survive in the Arctic and Amazonian populations survive in the Amazon, they do it by means of specific knowledge. If Deutsch were suddenly transported to the primeval Great Rift Valley, he would die for lack of knowledge. Without the requisite knowledge, humans will die virtually anywhere. With the requisite knowledge, encoded in brains, genes, computers, or other substrates, humans can survive virtually anywhere, on the Earth or elsewhere in space:

Whether humans could live entirely outside the biosphere—say, on the moon—does not depend on the quirks of human biochemistry. Just as humans currently cause over a tonne of vitamin C to appear in Oxfordshire every week (from their farms and factories), so they could do the same on the moon—and the same goes for breathable air, water, and comfortable temperature and all their other parochial needs. Those needs can all be met, given the right knowledge, by transforming other resources.

Deutsch explains that even today humans possess the technology to colonize the Moon and other stereotypically harsh environments. At this time in history, colonizing the moon would be prohibitively expensive. But right now you can buy a 4-terabyte hard-drive on Amazon for under 100 dollars. In 1980, that much storage cost about 772 million dollars. The price of technology frequently undergoes enormous reductions as science moves forward. Given that the price of digital memory was divided by millions in just a few decades, imagine the extraterrestrial societies we could conceivably build after perhaps a few centuries of compounding scientific and economic growth.

However, my argument is not that we will ever colonize space, nor that we should plan to do so. As Neil deGrasse Tyson argues, it will probably be trivial to adapt to a wide range of Earth climates long before it is feasible to colonize the Moon or Mars. Rather, I am pointing out that any dependence we have on specific environmental conditions is the result of insufficient knowledge.

Capitalism and the production of knowledge

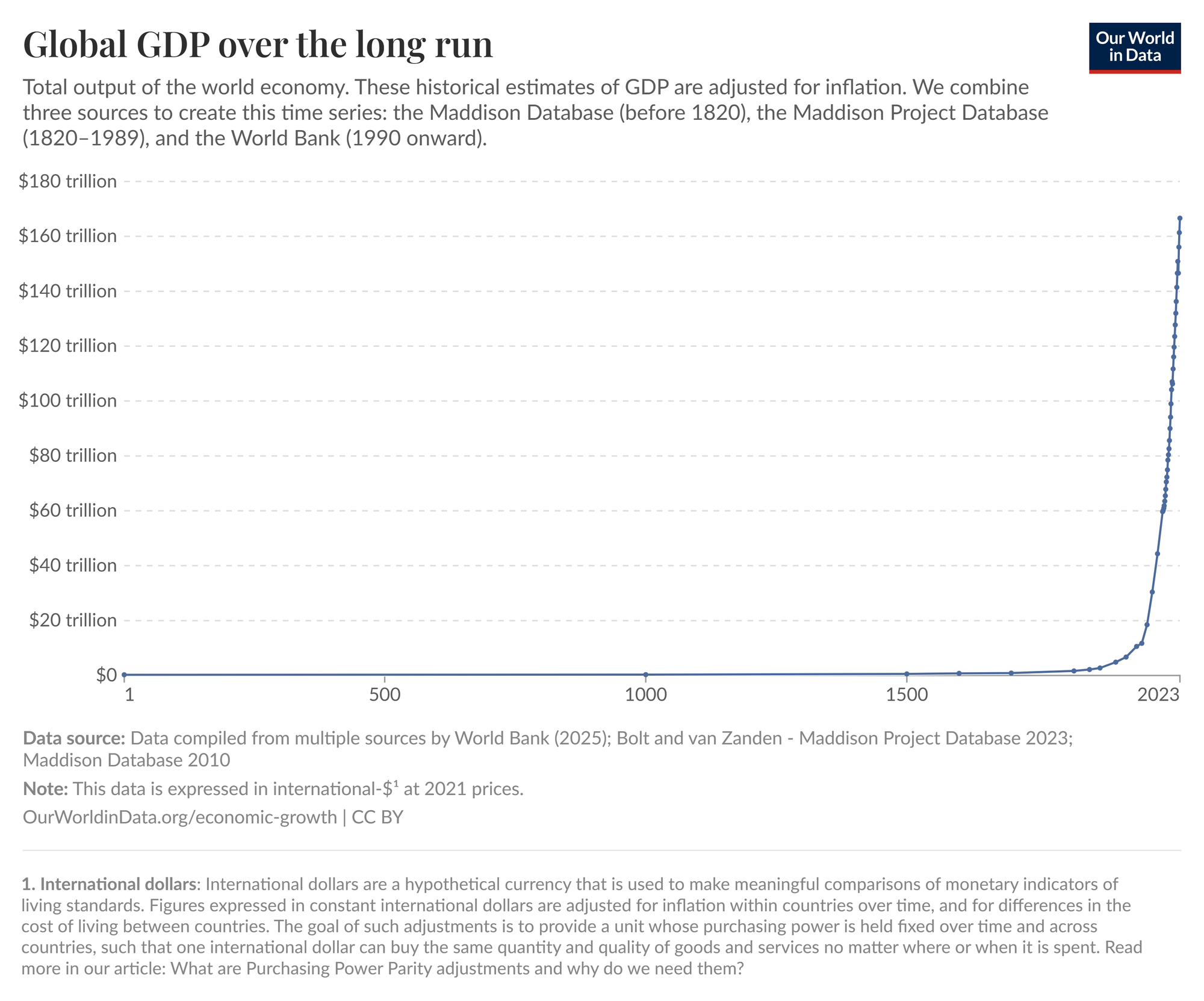

Throughout nearly all of human history, widespread economic growth per capita did not exist. Productivity per capita was ubiquitously stagnant; generation after generation, millennium after millennium, extreme poverty remained nearly universal and large-scale economic progress was not even imaginable. Virtually everyone lived on less than $3.50 per day in today’s dollars according to research from University of Oxford economist Max Roser, and the average person lived on much less. That’s even worse than it sounds, because (among other reasons) most of the things we can buy today had yet to be invented, and people didn’t have access to most of the information that informs our purchases in the 21st century.

Then, starting in Western Europe in the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, an unprecedented breadth of optimism emerged and turned wealth (resources hoarded away in vaults and mattresses) into capital (resources invested in future production and discovery). Thus, capitalism was born, and with it, exponential economic growth began to spread across most of the Earth (a process that continues to this day). As a result, both the rich and the poor are consistently getting rapidly richer for the first time in human history. Whereas 94 percent of the population was in extreme poverty as recently as 1820, in 1990 the number was down to 36 percent, and in 2015 the number was less than 10 percent. And as the world gets wealthier, countless important things proliferate, such as access to nutrition, freedom from violence, improvements in life expectancy, and of course, the access to and production of scientific and technological knowledge.

Knowledge is produced and spread in many ways. Education is one crucial variable, for the purpose of having both an educated population of innovators and a thriving research community. According to research from the Brookings Institute, educational opportunities and outcomes for the affluent radically exceed those for the poor—not just between countries, or within them, but everywhere. This is to be expected. Whether funded by individuals or government programs, it costs a lot of resources to build strong educational institutions and invest in educating generations of students. Poor populations who can barely afford shelter, clean water, food, and medicine don’t have much left over to invest in less immediate necessities such as education. And of course, this creates a feedback loop with causation running in both directions—if a population is uneducated, escaping poverty is much more difficult; if a population is poor, investing in education is much more difficult.

Another foundational tool for knowledge production is innovation, which capital and profit motive facilitate. A large amount of innovation comes from excess capital being invested in new research and development. Poorer populations, whether subnational, national, or global, have less to invest in prospective new inventions and processes of which the details are unpredictable in advance. No system incentivizes useful investments and disincentivizes wasteful investments better than the capitalist system, in which the investor’s own capital is on the line. Incentives and wealth are two main reasons why all of the most innovative nations, such as the top 10 on the 2020 Bloomberg Innovation Index, are capitalist countries. The sociologist Susan Cozzens at the Georgia Institute of Technology offers a succinct description of the process:

In the classic literature of the economics of innovation, private firms are the driving force. They seek competitive advantage in the market by introducing new products that give them a temporary monopoly. By charging high prices during the period of temporary monopoly, the firm makes profits and grows. Introducing new processes can result in competitive advantage if that step reduces costs or increases productivity. In this view, firms drive innovation in order to survive and win in the marketplace.

Indeed, no serious critics of capitalism argue that any other system produces greater material wealth and innovation. Even Marxists, capitalism’s most vehement antagonists, generally acknowledge that no system has ever produced more innovation and abundance. In The Communist Manifesto in 1848, Marx and Engels wrote this:

The bourgeoisie [capitalist class], during its rule of scarce one hundred years, has created more massive and more colossal productive forces than have all preceding generations together. Subjection of Nature’s forces to man, machinery, application of chemistry to industry and agriculture, steam-navigation, railways, electric telegraphs, clearing of whole continents for cultivation, canalisation of rivers, whole populations conjured out of the ground—what earlier century had even a presentiment that such productive forces slumbered in the lap of social labour?

If only Marx and Engels could see how drastically the affluence of the proletariat has grown under global capitalism since then.

Environmental technology

In 1894, just 21 years before Einstein’s theory of general relativity, the Nobel Prize-winning physicist Albert Michelson famously proclaimed, “The more important fundamental laws and facts of physical science have all been discovered, and these are now so firmly established that the possibility of their ever being supplanted in consequence of new discoveries is exceedingly remote.” Some phenomena, like blizzards and thunderstorms, are somewhat predictable to those with the requisite equipment and training. But the future of human knowledge is no such phenomenon. Discoveries, by their very nature, are unknown until they are not. Innovations are often unimaginable until they occur because the act of imagining them is what brings them into existence.

The history of failures to predict future knowledge is long and robust. In 1901, two years before they both achieved flight by aircraft, Wilbur Wright said to his brother, “Don’t think men will fly for a thousand years.” In 1932, just six years before the successful splitting of the atom, Albert Einstein said, ”There is not the slightest indication that nuclear energy will ever be obtainable.” In 1957, 12 years before Neil Armstrong set foot on the Moon, the father of radio Lee de Forest stated, “Man will never reach the Moon regardless of all future scientific advances.”

Even after world-changing technologies are invented, estimates of their utility are often wildly inaccurate. The Internet, cars, and telephones were all dismissed as insignificant inventions in the years preceding their universal ascendance. So we should be skeptical when we see publications like the BBC, Bloomberg, and Forbes denying the plausibility of imminent technological advances on our climate problems. The truth is nobody has any idea what salutary innovations and discoveries do or do not exist in our imminent future.

Many popular technological solutions to environmental issues have already been proposed in recent years. Carbon capture and sequestration technology is endorsed by climate scientists at the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) as well as by United States Congress members from both the Democratic and Republican parties. Inventions are being implemented to remove plastic from the oceans. Sea walls are being engineered in some coastal communities and considered at larger scales to mitigate sea level rise.

In The Climate Casino, Nordhaus writes: “Current estimates are that geoengineering would cost between one tenth and one hundredth as much as reducing CO2 emissions for an equivalent amount of cooling.” But at their present level of development, such technologies are inadequate to the full scope of the problem because they don’t sufficiently address certain dangers such as ocean acidification. Therefore, many environmentalists prefer extreme reductions in carbon emissions, which would stop anthropogenic climate change at its root. But anthropogenic climate change is not just a phenomenon of the future. The Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, CNN, and other news organizations have noted that it is already having serious effects here and now. The transition from predicted impact to experienced impact took place decades ago. So, how well are we adapting so far?

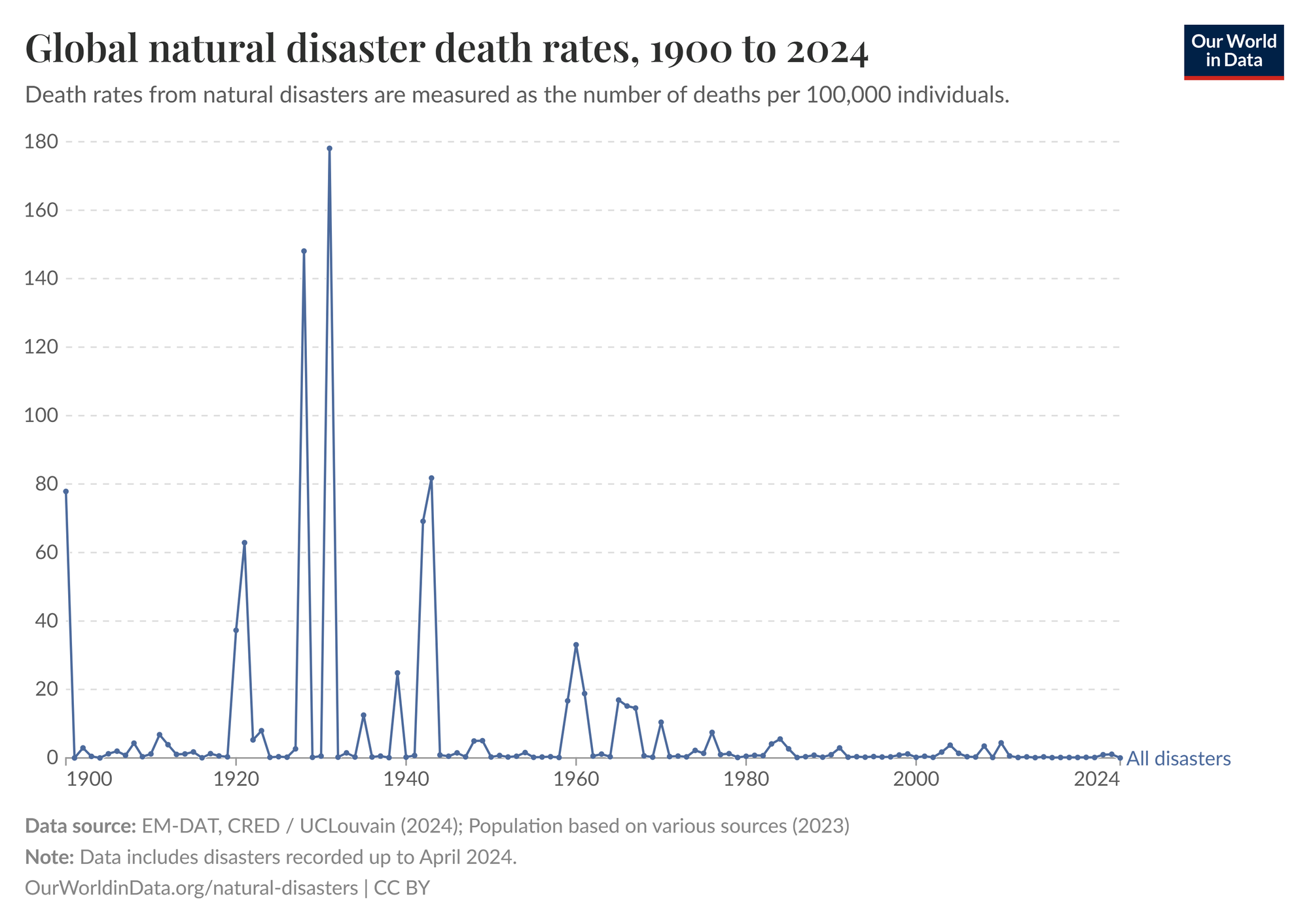

Scientific American reports that global warming may already be responsible for 150,000 deaths worldwide each year due to its effects on the frequency and scale of floods and hurricanes, droughts and heat waves, spread of vector-borne diseases, and other factors. However, research from the Reason Foundation shows that deaths caused by extreme weather events have declined by more than 90 percent since 1920. University of Oxford economist Max Roser’s research shows that the burden of disease, famine, and other relevant problems have also declined in recent years and decades (the disease statistics cited above are older than the COVID-19 pandemic, but there is no evidence that COVID-19 is directly exacerbated by climate change like vector-borne diseases such as malaria and dengue are). And overall life expectancy has risen globally from about 34 years in 1900 to about 72 years in 2019.

Why are climate-related death rates declining overall while climate change seems to be causing more deaths? Because as economic activity continues to drive up carbon emissions, the resulting growth rates give more communities access to strongly built and climate-controlled buildings, medical education and supplies, life-saving infrastructure such as hospitals and clean water, and many other enormous advantages. When the media and activists argue that burning fossil fuels has not been worth the climate-related damage to human life, they are counting the victims of climate catastrophe while ignoring the beneficiaries of economic growth in developing countries and elsewhere. That is a mistake because the two are inextricably linked.

Choose your own extinction

Of course, just because we’ve adapted extremely well so far doesn’t mean the trend will continue. Dangerous tipping points may yet accelerate the problem beyond our capacity to respond. As living organisms, we have a problem of evolutionary magnitude: we adapt gradually in an environment that can change rapidly. If we go on existing like any other animal, our niche will eventually change so quickly that we won’t be able to adapt fast enough. This has happened to 99.9 percent of all known species since the beginning of life on Earth roughly four billion years ago. These changes have ranged from asteroid impacts, to volcanic eruptions, to viral pandemics, and of course to human activity in recent millennia, and are typically unpredictable to the species they eliminate because they come from outside the limited context in which those species evolved.

Some argue that humans are just another mammal like any other, and that all our claims of exceptionality have been ignorant hubris. If this is true, we are almost certainly doomed to relatively imminent extinction by forces beyond our influence. But thinking this way about the human species does not quite account for the implications of the economic growth trend of the last few centuries. In his book Scale, former Santa Fe Institute president Geoffrey West, whose renowned scientific research put him on Time Magazine’s 2006 list of the 100 most influential people in the world, discusses a profound biological fact about mammal species: they virtually all have the same average number of heartbeats per capita. An average elephant has a long lifespan but a slow heart-rate, and an average mouse has a short lifespan but a fast heart-rate. It all balances out to roughly one-and-a-half billion heartbeats over the course of a lifetime. Other classes of animals follow similar metabolic scaling laws.

A few hundred years ago, before the rise of capitalism, humans were no different—they lived roughly 35 years on average and had about one-and-a-half billion heartbeats just like any other mammal. But gains in knowledge since then, such as innovations in medicine, agriculture, and government, have roughly doubled our life expectancy and with it our average number of heartbeats per lifetime (some dogs and other domesticated animals have been similarly altered by access to human innovations). This constitutes a totally unprecedented departure from the biological status quo.

Technological knowledge, fueled by capital, has allowed us to do many things categorically unlike the achievements of other species as far as we know. The universal extinction paradigm, which has limited all mammal species so far to one million years or less, should be high on our list of patterns to break. We don’t know what existential threats will come or how long we have to prepare for them, but we can’t expect human ingenuity to rush us past the finish line at the last minute without a context of widespread continuous technological and scientific progress until that point—a project it seems only capitalism can hope to fund.

David Deutsch observes that the word “sustain” generally refers to the absence or prevention of change. This is what environmentalists such as Naomi Klein and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez would like to do with our environment by ending capitalism. Their solution to climate change is what all non-human animals have always done: leave the environment basically unaltered by refraining from large-scale production, and wait around to go extinct. Unfortunately, as Deutsch writes, “Static societies eventually fail because their characteristic inability to create knowledge rapidly must eventually turn some problem into a catastrophe.” Thus, it is not that capitalism is the problem and sustainability is the solution, but that sustainability is the problem and capitalism is the solution.

Every year, global capitalism allows more research and development departments to be funded. Every day it gives more citizens of affluent and developing nations the material wealth required for better education and information technology. Economic growth, coupled with rising carbon emissions, might lead to a climate apocalypse—or it might continue to bring us material and technological salvation. We cannot really know in advance. But we would be crazy to choose the time-tested alternative to capitalism: extinction by stagnation.