Books

Easy Rider: 50 Years Looking for America—A Review

Easy Rider is an important movie—much more important than a simple measure of its quality would suggest—which is probably why the American Film Institute, among others, continues to rate it so highly.

A review of Easy Rider: 50 Years Looking for America by Steven Bingen, Lyons Press (November 2019) 200 pages.

It was the 1990 comedy Flashback that sparked my interest in Easy Rider (1969) when I was eight or nine years old. In the former, Dennis Hopper plays an aging 60s dissident, busted after 20 years on the lam, who gets taken cross-country by a no-nonsense FBI agent, played by Kiefer Sutherland. Naturally, the straight-laced fed can’t keep his laces very straight after Hopper doses him (or pretends to dose him) with LSD, releasing the young Republican’s inner hippie. At one point, Hopper declares, “It takes more than going down to your local video store and renting Easy Rider to be a rebel.” For some odd reason lost on me now, I liked this airy nothing of a movie and so, of course, insisted that my family rent Easy Rider the next time we visited our local video store. Strangely, I liked that too, though, again, I’m not quite sure why. Maybe it was the music—all that Steppenwolf, Jimi Hendrix, and Roger McGuinn. Maybe it was the motorcycles—those souped-up Harleys with their teardrop gas tanks. Or maybe, like Sutherland’s character in Flashback, I was just easily charmed by members of the counterculture.

Needless to say, I wasn’t alone. Though shot on a shoestring budget, Easy Rider ended up being the fourth-highest-grossing film of 1969, raking in around $60 million worldwide.1 Its leads, Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda, became (albeit briefly) Hollywood’s hottest new wunderkinds. And it kick-started Jack Nicholson’s sputtering career, propelling him out of B-movies and into 70s superstardom. In the years since, the film’s production has become nearly as famous as the movie itself, largely thanks to historian Peter Biskind’s 1998 bestseller, Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, which portrayed the shoot as an orgy of chaos, rife with drugs, brawls, and monumental artistic pretention. Reading it, one wonders how Hopper and company made a coherent film at all, let alone one that the American Film Institute would later rate one of the best 100 American films of all time. (They ranked it 88th, well below The Third Man [1949] but still ahead of Pulp Fiction [1994] and Yankee Doodle Dandy [1942].) Now, to mark the film’s 50th birthday, author Steven Bingen has written a new book about the picture, Easy Rider: 50 Years Looking for America. Unlike Biskind, though, Bingen isn’t only interested in the film’s production; he’s equally interested in its reception over the decades. What is it, his book asks, that, half a century on, continues to draw so many viewers to this movie?

To some extent, obviously, it’s the fact that Easy Rider is a late-60s time capsule, conveying not just the look and sound of the period but the zeitgeist, as well—that blend of idealism, radicalism, optimism, and solipsistic smugness that flourished between the Summer of Love and Altamont. The idea for the movie, fittingly, was born in a cloud of marijuana smoke, coming to Fonda one evening in a Toronto motel room as he gazed at a still from one of his recent movies, The Wild Angels (1966). Bikers, it dawned on him as he puffed on a joint, were modern cowboys. Not a brilliant insight, to be sure, but Fonda reasoned that with his Hollywood connections it wouldn’t be too difficult for him to raise the money to produce a contemporary Western starring himself. Despite his illustrious surname, he was still, after half a decade in the business, mostly stuck in low-rent indie movies and television shows, his career eclipsed by his more famous father (Henry) and sister (Jane). So he was eager to make his own mark. He figured he’d just need someone to play his partner in the movie and someone (maybe the same someone) to direct it, which is why he called his friend Dennis Hopper that very night.

Hopper was a bona fide countercultural character, though not necessarily one that you’d have wanted to go on a road trip with. His explosive temper, frequent inebriation, and habit of brandishing loaded firearms soured more than one friendship, including, eventually, his friendship with Fonda, which curdled before the shooting of Easy Rider was even over. By the time Fonda called him up, his once promising screen career—which began when he was just 19, alongside James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause (1955)—had more or less gone up in smoke. You could blink and miss him in Cool Hand Luke (1967), and he gets barely a minute of screen time before Ben Johnson guns him down in Hang ‘Em High (1968). Yet Hopper was genuinely talented, and not just as an actor. As his film career waned in the mid-60s, he proved himself to be an adept stills photographer, shooting celebrity layouts for Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar, publicity stills for bands like the Byrds and the Grateful Dead, and gritty reportorial images from the civil rights movement. His ambition, though, was to be a film director.2

After Easy Rider became a hit, Hopper and Fonda spent much of the rest of their lives squabbling—both in print and in court—over credit for dreaming up its story. According to Fonda, the pair plotted most of the film together, sitting out on Fonda’s tennis court, while his daughter, Bridget, pedaled her tricycle around them.3 Hopper (less credibly) liked to claim that he wrote the entire thing himself in 10 days.4 Considering how thin the plot is, it’s hard to see what they were getting so worked up about. The film follows two buddies, played by Fonda and Hopper, who strike it rich in a drug deal and then use the proceeds to motorcycle across the country to Mardi Gras, meeting colorful characters—hippies, rednecks, an ACLU lawyer—along the way. After dropping acid in a graveyard with two prostitutes, the duo set out eastward again, only to be shot dead by hillbillies on the highway.

Strangely, this barebones outline tickled the interest of novelist-cum-screenwriter Terry Southern, who—either out of generosity or out of sheer need for amusement—agreed to write the screenplay for $350 a week, rather than the $100,000 per script he was commanding at the time.5 Still riding high from the success of Dr. Strangelove (1964), which he’d penned with Stanley Kubrick a few years before, Southern gave the project something neither Fonda nor Hopper could: credibility. (He also gave it its title. An “easy rider” is a prostitute’s boyfriend, getting his “ride” for free.) It was Southern’s name on the script as much as Fonda’s that got them through the front door of Raybert Productions, an indie film company run by Bert Schneider and Bob Rafelson, two brash young upstarts who’d just scored big by producing the Monkees TV series. Surprisingly, they too were excited by the story. “This guy”—meaning Hopper—“is fucking crazy,” Rafelson reportedly told the duo, “but I totally believe in him, and I think he’d make a brilliant film for us.”6

How brilliant the film actually is remains a matter of some dispute. Reviews at the time of the picture’s release were generally positive. “It was inevitable that a great film would come along, utilizing the motorcycle genre, the same way the great Westerns suddenly made everyone realize they were a legitimate American art form,” a 27-year-old Roger Ebert wrote in the Chicago Sun-Times. “Easy Rider is the picture.”7 When the American Film Institute reissued their Greatest American Films list in 2008, Easy Rider had ascended four spaces, beating out, among others, Bringing Up Baby (1938) and 12 Angry Men (1957).

Whatever convinced the Institute that they’d underrated Easy Rider the first time out, it almost certainly wasn’t the film’s craftsmanship, which, by the standards of any era, has never been anything more than workmanlike. Matches on action don’t always match. Continuity mistakes abound. (At one point, as Hopper and Fonda ride down the highway, you can see Hopper turn and start to talk to the cameraman.) Worst of all are the New Orleans sequences. Because they were working on a limited budget, Fonda decided that they’d grab the Mardi Gras footage guerilla-style, in real-time, rather than trying to recreate it with paid extras. Unfortunately, he mistook the date of the festival, and the production was forced to rush to New Orleans to catch the revelry before it ended. Things didn’t go any better once they got there. Instead of hurrying to grab as many shots as he could, Hopper spent the first two hours of the first day of production haranguing the crew in their motel parking lot, yelling, “This is my fucking movie, and nobody is going to take it away from me!”8 As a result, you hardly see any of Mardi Gras in the finished film, and the footage that is used, because it was shot on 16mm, doesn’t blend in with the rest of the picture. It’s as if the characters wandered out of a Hollywood movie and into a student film.

Bingen acknowledges these faults but doesn’t find them particularly off-putting. He tends, though, to ignore the movie’s main defect, which mars it much more gravely than its slapdash construction: its self-absorption. This deficiency can be largely blamed on Fonda, who, as the film’s producer, chose to make his character, Wyatt, the moral spokesman for the movie. Not only does he get the loftiest lines but even in his more prosaic moments he tends to preach more than speak, as though he were some kind of modern-day prophet. When Hopper scoffs at a hippie commune they visit, Fonda sets him straight: “They’re gonna make it. Dig, man. They’re gonna make it.” When they lunch with a middle-aged farmer and his family, Fonda shows that he’s simpatico with them, too: “You do your own thing in your own time. You should be proud.” The women, meanwhile, are essentially interchangeable, thrown in merely to tag along with the men. At a southern diner, the local girls flock around the protagonists as though they’re rock stars, making the resident rednecks green with envy. They aren’t just two drug dealers out on a road trip; they’re rebels, sex symbols, and men of the people.

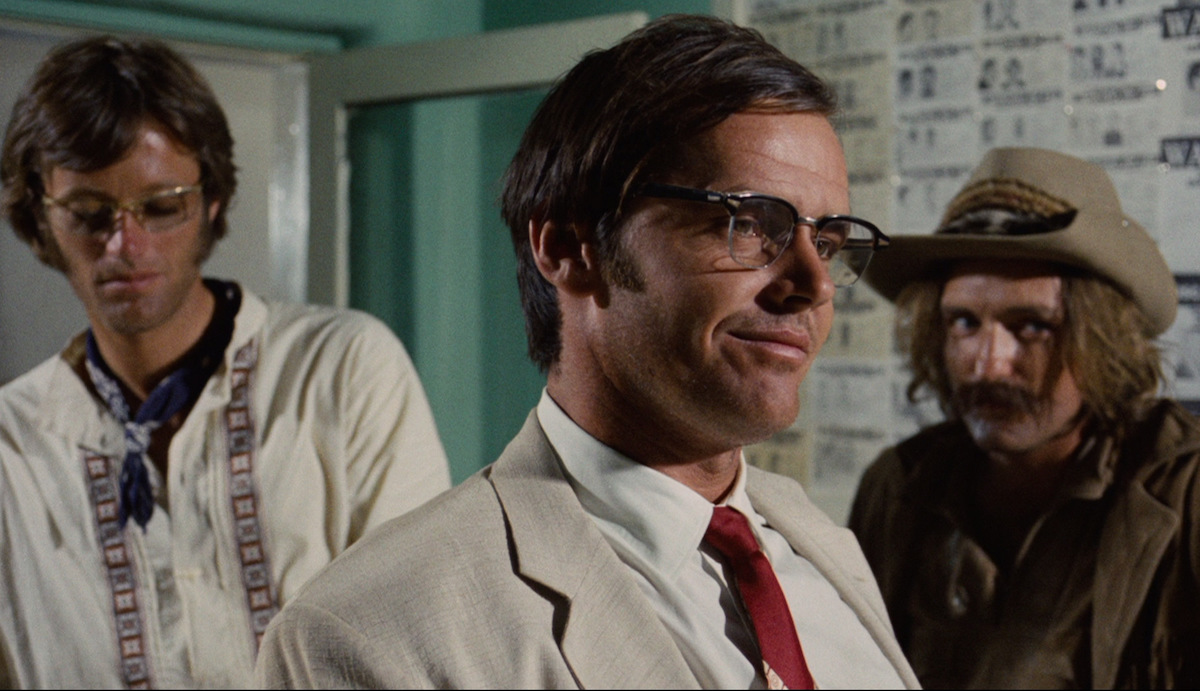

The best thing about the film, by near-unanimous agreement, is Jack Nicholson, who plays a boozy lawyer the heroes pick up along the way to New Orleans. Though he shows up 45 minutes into the movie and dies less than half an hour later, Nicholson runs—or, perhaps, rides—away with the picture, stealing it out from under the two protagonists the moment he pops up beside them in a dilapidated jail cell. In part, this is because he’s totally unselfconscious onscreen. Unlike either Hopper or Fonda, he’s not trying to be cool. Far from it: his white suspenders, gold football helmet, and habit of exclaiming nik, nik, nik every time he takes a pull from his whiskey bottle are about as hip, in Easy Rider’s world of throaty choppers, as a Vespa with a sidecar. But he’s completely natural, which both makes him the most compelling person in the movie and, paradoxically, the coolest. As Nicholson’s biographer Patrick McGilligan observes, though Fonda was trying to channel his father’s decent everyman persona, it was Nicholson who came off more like Henry Fonda: “Nicholson was the one playing the pure American.”9

It was the film’s producers, Bob Rafelson and Bert Schneider, who wanted Nicholson for the role of George Hanson. Still stuck in B-movies after 15 years in Hollywood, Nicholson was, at the time, thinking about giving up acting for directing.10 He’d already written several screenplays—including The Trip (1967), starring Fonda and Hopper—and had produced Rafelson’s first feature as a director, Head (1968). By casting Nicholson in Easy Rider, Rafelson and Schneider reasoned that they’d be getting a two-for-one deal: an actor to fill the still-vacant George Hanson part and a friend who could keep an eye on things for them, making sure the production didn’t crash and burn with Hopper at the wheel.

In truth, Nicholson was never really cut out to work behind the camera. (His periodic stabs at directing over the years have made that fact quite clear.) Yet, he did end up aiding the production of Easy Rider—that is, in addition to playing the film’s most likeable character. Hopper’s initial cut of the film ran to nearly four-and-a-half hours. The diner scene alone went on for more than 20 minutes. None of this pleased Schneider, who promptly arranged for Hopper to take a vacation in New Mexico, giving him the New Orleans footage to keep him busy while he was gone. With Hopper out of the way, Schneider then handed the project over to Nicholson, editor Donn Cambern, and future director Henry Jaglom, who managed to whittle it down to 95 minutes. Hopper, when he returned, was furious. “You’ve ruined my film,” he complained. “You’ve made a TV show out of it.”11 Schneider, though, had the final word. “Bert was the heroic savior of that movie,” Hopper’s ex-wife Brooke Hayward recalls. “Without him, there never would have been an Easy Rider.”12

Bingen concedes upfront that his book was written in a hurry—rushed to press so that it could hit shelves before the end of Easy Rider’s semi-centennial—and the haste often shows.13 Errors of fact litter the way. Nicholson didn’t win an Oscar in 1988.14 (He won in ’76, ’84, and ’98.) The film’s original title was The Loners,15 not The Losers.16 And the flag painted on Peter Fonda’s gas tank is the Stars and Stripes, not the “stars-and-bars,” which was the official flag of the Confederacy.17 Bingen, however, does have one asset that most other film critics do not possess: an extensive firsthand knowledge of motorcycles. This allows him to catch details that only a devoted hog-head would notice—that, for instance, the bikes in the film, for all their apparent splendor, are more show ponies than stallions, lacking both the cushion and the maneuverability that one would actually want on a cross-country journey.18 When it comes to the film itself, though, his perceptions blur, and in his eagerness to sell the film as a cinematic touchstone he has a tendency to drift into rhetorical excess. “Without Easy Rider, there would have been no George Lucas, so no Star Wars; no Francis Ford Coppola, so no Godfather; no Steven Spielberg, no Martin Scorsese, no Brian De Palma—no modern Hollywood,” he grandly declares, failing to note that Coppola, Scorsese, and De Palma were already feature film directors at the time of Easy Rider’s release.19 “While it’s a movie, unlike any other film out there, it’s also a lifestyle.”20 Tell that to Star Wars fans.

The main problem with the book, though, is simply that it runs out of gas, meandering off onto long tangents about biker culture and the film’s 2012 sequel, Easy Rider 2: The Ride Back, a Z-list retread brought to the screen by Cincinnati lawyer Phil Pitzer, who also stars in it. This is unfortunate because a lot of worthwhile information falls by the wayside. The book fails to mention the film’s original opening scene, set at a country fair, that got left on the cutting room floor; hardly discusses Hopper’s pre-Easy Rider background; and only gives the barest précis of either Hopper or Fonda’s lives after the film’s release.21 Neither one, as it turned out, was ready for the success that came their way. For Fonda, the downhill slide was fairly gentle, slowly sloping back into the same kind of B-movies he’d been making before Easy Rider. For Hopper, the crash was more precipitate but so, too, was his comeback. His directorial follow-up, the inauspiciously titled The Last Movie (1971), turned out to be a fantastic failure, and Hopper spent the next decade-plus mired in a near-permanent state of inebriation. Once he’d kicked his addictions, though, he found a new niche for himself, playing a series of increasingly outlandish villains; began directing again (to modest acclaim); and became a tough-on-crime Newt Gingrich supporter, more than happy to make fun of his younger self.22

Bingen is right about one thing, though: Easy Rider really is an important movie—much more important than a simple measure of its quality would suggest—which is probably why the American Film Institute, among others, continues to rate it so highly. It’s the type of movie that could have only succeeded when it did. The tone would have been wrong for any other moment in time. A few years before, no producer in Hollywood would have touched a film with two drug-dealing heroes. A few years later, no audience member in America would have bought its happy talk about communards living off the land.

Though Bingen overstates the case, he’s not wrong to suggest that Easy Rider had a major impact on Hollywood history. The American movie business, by the late 60s, was seriously struggling, losing eyeballs to television and—no longer able to force distributors to take their product sight-unseen—desperate to grab ahold of anything that turned a profit: CinemaScope, 3D, opulent musicals like The Sound of Music (1965). The industry was, thus, primed for Fonda and Hopper to come along, and when their $360,000 movie became a blockbuster, it unlatched the studio gates for a slew of other young filmmakers to follow in their footsteps.23 As Hopper himself explained, in one of his rare moments of modesty, “Since I had directed, it must mean anybody could direct.”24 That may sound like a joke, but it’s what people in Hollywood were actually thinking after Easy Rider’s release. “The industry imploded,” writer-director Paul Schrader recalls, “the door was wide open and you could just waltz in and have these meetings and propose whatever. There was nothing that was too outrageous.”25

References:

1 Bingen, Steven. Easy Rider: 50 Years Looking for America. Lyons Press, 2019, p.76

2 Winkler, Peter L. Dennis Hopper: The Wild Ride of a Hollywood Rebel. Barricade Books, 2011, p.1181

3 Bingen, p.7

4 Winkler, p.5193

5 Bingen, p.8

6 Winkler, p.1968

7 Bingen, p.72

8 Fonda, Peter. Don’t Tell Dad: A Memoir. Hyperion, 1998, p.254

9 Bingen, p.43

10 McGilligan, Patrick. Jack’s Life: A Biography of Jack Nicholson. W.W. Norton & Company, 2015, p.197

11 Biskind, Peter. Easy Riders, Raging Bulls: How the Sex-Drugs-and-Rock ‘N’ Roll Generation Saved Hollywood. Simon & Schuster, 1998, p.72

12 Ibid., p.71

13 Bingen, p.xii

14 Ibid., p.30

15 Biskind, p.61

16 Bingen, p.6

17 Ibid., p.21

18 Ibid., p.22

19 Ibid., p.86

20 Ibid., p.xiv

21 Hill, Lee. Easy Rider. BFI Publishing, 2004, p.40

22 Ibid., p.63

23 Winkler, p.1975

24 Ibid., p.2463

25 Biskind, p.22