As Erdoğan Weaponizes Turkey's Migrants, Greece Pays the Price

Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis tweeted on Sunday. “The borders of Greece are the external borders of Europe. We will protect them.”

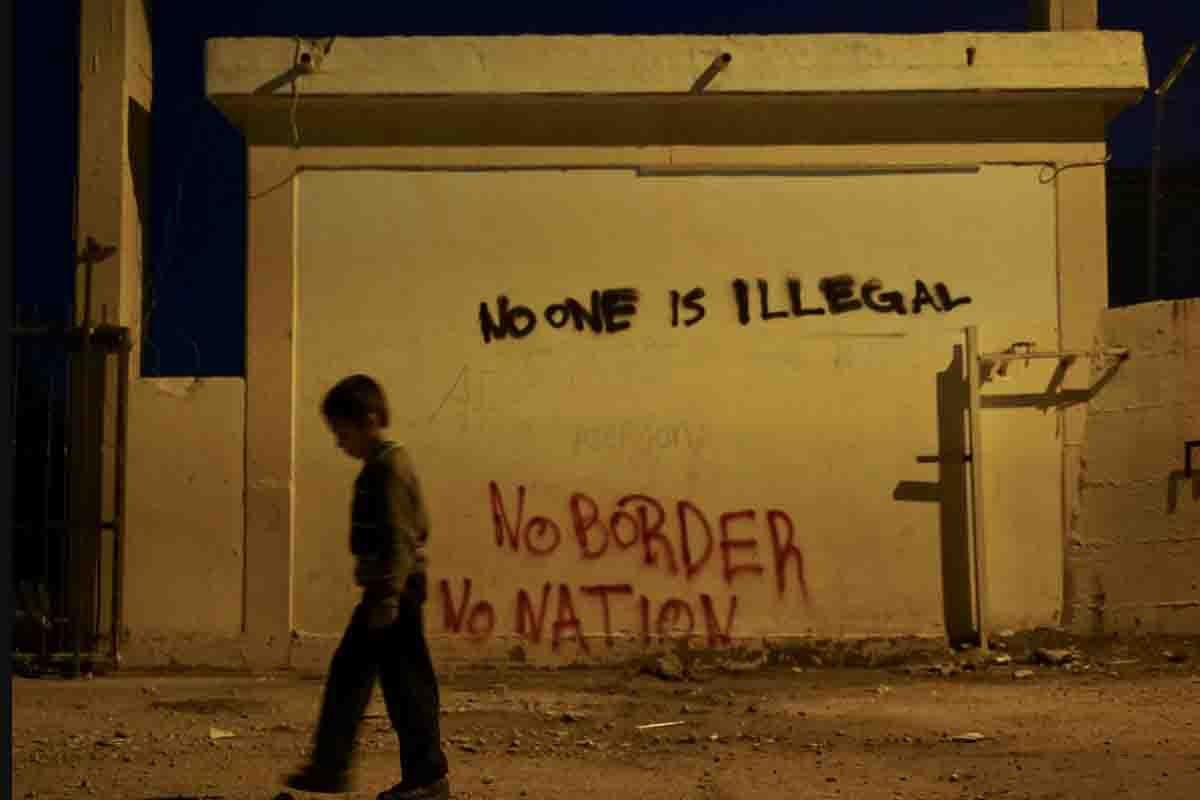

Thousands of migrants and refugees have massed at the Greek-Turkish border, attempting to pass into Europe. Europe got a first test of what it would look like if Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan makes good on his February 28th declaration to open the floodgates and deluge the EU with a new wave of asylum seekers.

Last week, Turkish forces suffered heavy military losses in Syria, where Erdoğan has been pursuing an increasingly aggressive policy. He now is looking for a ceasefire in Idlib, site of the latest Turkish intervention and the last significant outpost of resistance to Bashar al-Assad’s Syrian regime. Erdoğan’s announcement regarding asylum-seekers seemed aimed not only at pressuring other countries to support his shifting war aims, but also at diverting attention away from a Syrian military quagmire into which Erdoğan recently poured 7,000 fresh troops.

In a brazen attempt to weaponize the migrant crisis, the country’s officials have begun providing free transport to thousands of refugees seeking entry into Greece. Lest anyone miss the message, Friday’s mini-exodus was broadcast live on Turkish television. Harried people were shown heading to the borders by bus, taxi, and on foot.

Over the weekend, Greece’s land borders with Turkey predictably turned into a border-enforcement battlefield, with skirmishes breaking out between westbound asylum-seekers and Greek police and soldiers. A Greek government spokesman called it “an organized mass attempt to violate Greece’s land and sea borders,” and accused Turkey of facilitating people-smuggling. On Sunday, a young child drowned after a boat capsized during a sea crossing—the first death since Turkey opened its border.

The situation signals a new phase in the European migration crisis, which has gradually moved off the front pages since 2016, when a deal between the EU and Turkey was struck, and the countries along the Balkan route to the north largely shut down their borders. It also signals the first major crisis faced by Greece’s conservative New Democracy government since it came to power in July.

The real danger for Europe will be if the battle raging for the last rebel holdout in Syria unlocks a fresh wave of refugees, and the Turkish leader also opens the border with Syria.

Greek authorities say they intercept around 10,000 attempts per day at various spots along the 120-mile border, parts of which are now blocked with barbed wire. Greece’s police and army also have made extensive use of tear gas to disperse migrants, who were throwing stones and even burning wood. According to the Greeks, some migrants are themselves armed with tear gas canisters that they suspect were provided by sympathetic Turkish officials.

In addition, Greece has used various non-violent means to repel asylum-seekers, using text messages and loudspeakers to warn them to remain in Turkey. “Do not attempt to enter Greece illegally, you will be turned back,” Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis tweeted on Sunday. “The borders of Greece are the external borders of Europe. We will protect them.” He also has requested the deployment of the EU’s Frontex’s rapid border-intervention team to supplement Greece’s own security forces.

It is unclear how many thousands of people are gathered these days at border crossing points and how many are trapped in the no-man’s land between the two countries. Turkey’s interior minister Süleyman Soylu said on Twitter that more than 100,000 migrants had left Turkey on Sunday via the Edirne border crossing. But the International Organization for Migration has estimated the number at only 15,000, at least for now.

The situation was much better on Tuesday morning, with the vast majority of the refugees having stepped back to the Turkish city of Edirne. Greek officials fear an even further rise of arrivals on the Greek islands, where it is more difficult to control the flows.

As for Erdoğan, he seems intent on fanning fears of an almost biblical sweep of humanity into Europe. “After we opened the doors, there were multiple calls saying ‘close the doors,’” he reportedly said on Monday. “I told them it’s done. It’s finished. The doors are now open. Since we have opened the borders, the number of refugees heading toward Europe has reached hundreds of thousands. This number will soon be in the millions.”

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees called on Greece to refrain from the use of excessive or disproportionate force, and to maintain systems for handling asylum requests in an orderly manner. But Turkey’s move has helped sap whatever humanitarian spirit remains in Greece. The Greek government announced on Sunday that it will no longer be accepting any new asylum applications for a month, while migrants will be returned immediately if possible without being registered. The country invoked Article 78.3 of the EU treaty “to ensure full European support” and to trigger provisional emergency relocation measures.

“Neither the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees nor EU refugee law provides any legal basis for the suspension of the reception of asylum applications,” it added, with the caveat that article 78.3 “cannot suspend the internationally recognized right to [asylum] emphasized in EU law.”

The situation could escalate further. Greek authorities say that thousands more migrants are reportedly gathering along the Turkish coastline, waiting to cross the Aegean Sea. More than 1,000 already have arrived on Aegean islands since Sunday morning. Camps there are already overpopulated, and the locals’ tolerance was exhausted long ago.

On Tuesday morning, the Greek Prime Minister visited the Evros region, on the north-east coast of the Aegean, with the presidents of the European Council, European Commission, and European Parliament, in a show of support for Athens. And an informal EU foreign ministers’ meeting is scheduled for Friday. But based on precedent, Greek officials are skeptical that any concrete action will come of it. The 2016 deal on migrants struck between the EU and Turkey was supposed to be part of an emergency solution, a temporary fix that would give European member states time to agree on a joint approach on migration issues more generally. But four years later, little progress has been made. The drop in migrant numbers gave EU policymakers the political room they needed to pretend the problem didn’t exist anymore. Thanks to this inaction, the EU will have to respond late to this follow-up crisis, too.

Erdoğan’s stunt is aimed not only at pressuring Europe, but sowing divisions among its member states: He hopes that Europe will appease him as a means to yet again avoid a definitive solution to the migration crisis. But EU leaders should remember that such a short-term fix would only ensure that these scenarios repeat themselves in the future, and that teeming masses of displaced and impoverished refugees and migrants will continue to be used as pawns.