Immigration

Greece: Tensions Rise Again As Migrant Crisis Escalates

Migration in the Mediterranean has increased in recent weeks to the highest level since the EU-Turkey deal in March, 2016, and Greece is back to being the main entry point for hopeful migrants.

For debt-stricken Greece, the migrant crisis is hardly over. The new center-right government is grappling with a surge in migration and deteriorating conditions in the country’s asylum centers.

Migration in the Mediterranean has increased in recent weeks to the highest level since the EU-Turkey deal in March, 2016, and Greece is back to being the main entry point for hopeful migrants. So far this year, some 36,000 people have entered the country through its sea and land borders, already surpassing last year’s influx of roughly 32,000. By contrast, the other two European frontline countries, Spain and Italy—both economically and politically less fragile than Greece—have received a total of 26,000 migrants together in 2019.

The situation could escalate even further; Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan threatens to re-open the route for migrants into Europe, if he does not receive adequate international support for his plan to resettle one million asylum seekers from Turkey to northern Syria. (Turkey has nearly 4 million Syrians, by far the biggest group of refugees.)

Meanwhile, conditions are worsening at Greek asylum centers. For the first time, migrants and refugees on the Greek islands number more than 21,000, in reception centers built to host less than 7,000 people. Thousands more people live in abysmal conditions outside the centers. Tents have been set up in open fields, where people are exposed to disease, violence and adverse weather.

In the infamous Moria camp on Lesbos island there is only one doctor per shift, who can attend only emergencies. There is also an acute lack of nurses and translators, according to aid groups. All the camps are experiencing large numbers of suicide attempts, but many suicidal migrants are routinely returned to the same living conditions after receiving emergency treatment.

Violence also remains a problem in the camps. Recently an unaccompanied minor died, and two others were injured in a knife attack at Moria. Securing more places around the country for unaccompanied minors has been declared a priority by authorities for years, but, at the moment, only some 1,200 unaccompanied minors out of a total of 4,200 live in appropriate facilities. The rest are being held in detention centers, temporary accommodation facilities, or live in the streets.

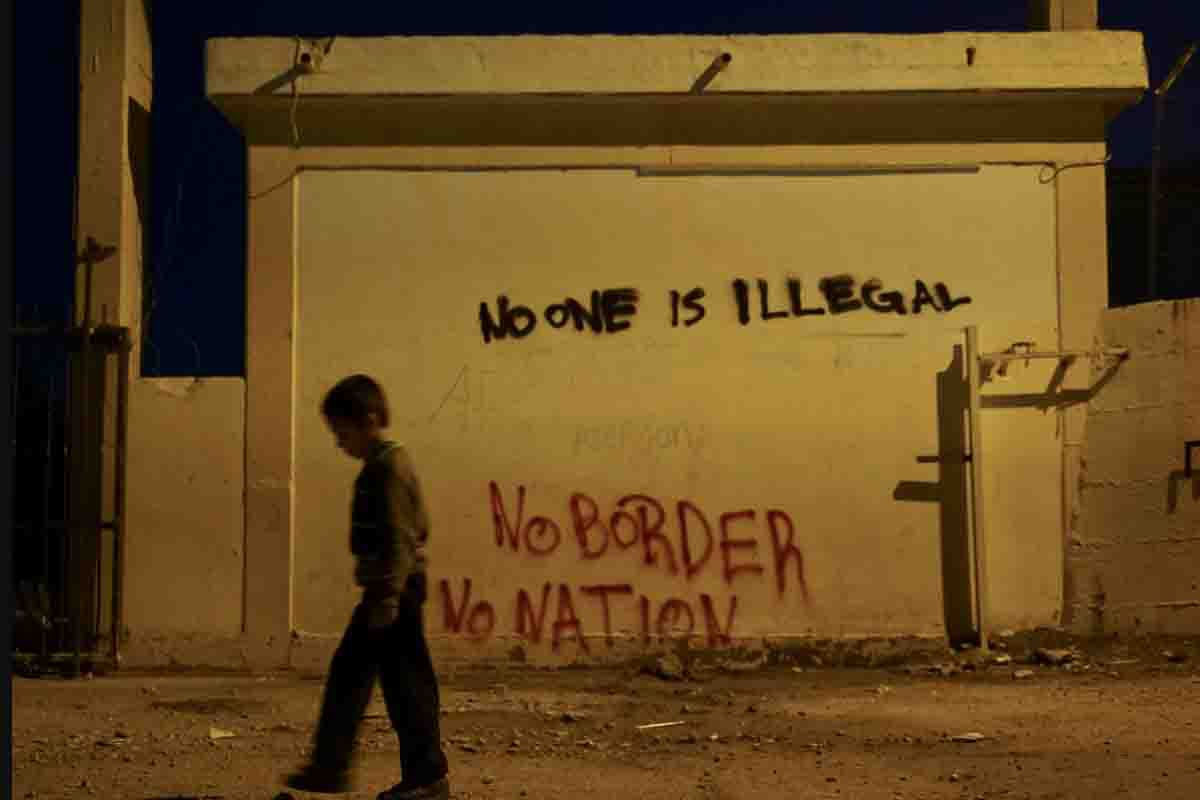

Meanwhile, racist attacks against immigrants are on the rise, according to local police. Earlier this year two violent attacks against migrants and refugees, including children, were reported, the first in organized reception facilities since the outbreak of the migration crisis.

Such grim conditions in the Greek camps cannot simply be attributed to a lack of funds in a country that struggles with an ongoing economic crisis. Nor is it a recent phenomenon. The previous left-wing government was heavily criticized by supporters and opponents alike for the tragic living conditions it offered migrants. Greek authorities have consistently failed to make effective use of EU funds—some €1.45 billion of a promised €2.21 has been paid out—for better management of the migrant influx. Partly due to the Greek state’s infamous inefficiency and red tape, and partly due to its inability to estimate migration flows, the local authorities’ response remains in a constant emergency mode. Aid groups have accused authorities of allowing conditions to deteriorate, as a deterrent to other would-be migrants.

Over-population at asylum centers is, in part, due to a new bottleneck on the Greek mainland: Since April, the number of asylum seekers transported out of the islands to other parts of Greece has decreased significantly. One reason is a lack of accommodations on the mainland. Another reason is that responsibility for transfers was supposed to be removed from The UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) and the International Organization for Migration (IOM) to the Greek state, which, according to several officials, was ill-prepared for the transition.

The government has moved some 1,400 people to better equipped—but still tent-based—camps in the mainland. It is currently exploring different ways to expand already existing camps or find new locations, such as abandoned army camps. But this news has not been well received in the Greek mainland. Local communities are protesting against the prospect of migrant camps being placed in or near their towns. Meanwhile, islanders feel a sense of abandonment, as they have been left to deal with two crises at once—the migrant crisis, and the lingering effects of the debt crisis.

As the migration issue is once again escalating in Greece, the center-right government, led by the New Democracy party, has chosen a novel approach: It plans to change the institutional framework for the asylum process, including the abolition of the right to appeal rejected applications. The new policy has been met with harsh criticism from opposition parties and international organizations, who question its legality and efficiency.

“The right to appeal is fundamental in the asylum process, according to European and international law,” says Stella Nanou, a spokesperson for UNHCR in Athens. “We understand and agree with the need for a faster and more dynamic asylum process, but the government has to safeguard that it will also be a fair one. We expect more clarifications and we will be there to consult the government throughout the process.”

The government says that it only aims to abolish the asylum appeals committees, but that those who wish to appeal can do so in court. However, organizations like Amnesty International and the Greek Council for Refugees say this could further delay the already extended asylum process, as the overloaded Greek courts will not be able to deal with the additional burden. The whole process would also become more expensive for the Greek state, which would be obliged to cover legal costs.

The New Democracy government also said it wants to move ahead with quick migrant returns to third countries, including Turkey. Such a solution will ultimately depend on whether third countries are willing to take migrants back. Furthermore, after a change of refugee policy and en masse deportations to Idlib, Syria, it is questionable whether Turkey can still be regarded as a safe third country, aid groups say.

In the meantime, conflict levels are rising in Greek society. Just three days into his new role, Labor Minister Yiannis Vroutsis decided to cancel legislation that granted access to national health care to all foreigners from non-EU countries without exceptions. “Our country is not an unfenced backyard,” he tweeted, announcing his decision.

This not only leaves the country exposed to epidemics. It also bars immigrant children from attending school, since they can’t be issued a required health care number. According to Gabriel Sakellaridis, head of Greece’s Amnesty International, this constitutes a violation of basic human rights.

A few weeks after Mr. Vroutsi’s announcement, in late August, police raided and evacuated anarchists’ collectives in the notorious neighborhood of Exarchia in downtown Athens, some of which were housing migrants and refugees, including women and children. The operation was heavily criticized by opposition parties and aid groups for the “theatrical” way in which it was set up: A helicopter flew above the area while armed police raided the squats, all intensely covered by Greek media.

Police spokesman Stravos Balaskas compared the police operation to a “silent vacuum cleaner” that “will gradually suck up all the garbage” in Exarchia. He later apologized, after facing a public backlash. Still, such language is indicative of current levels of animosity.