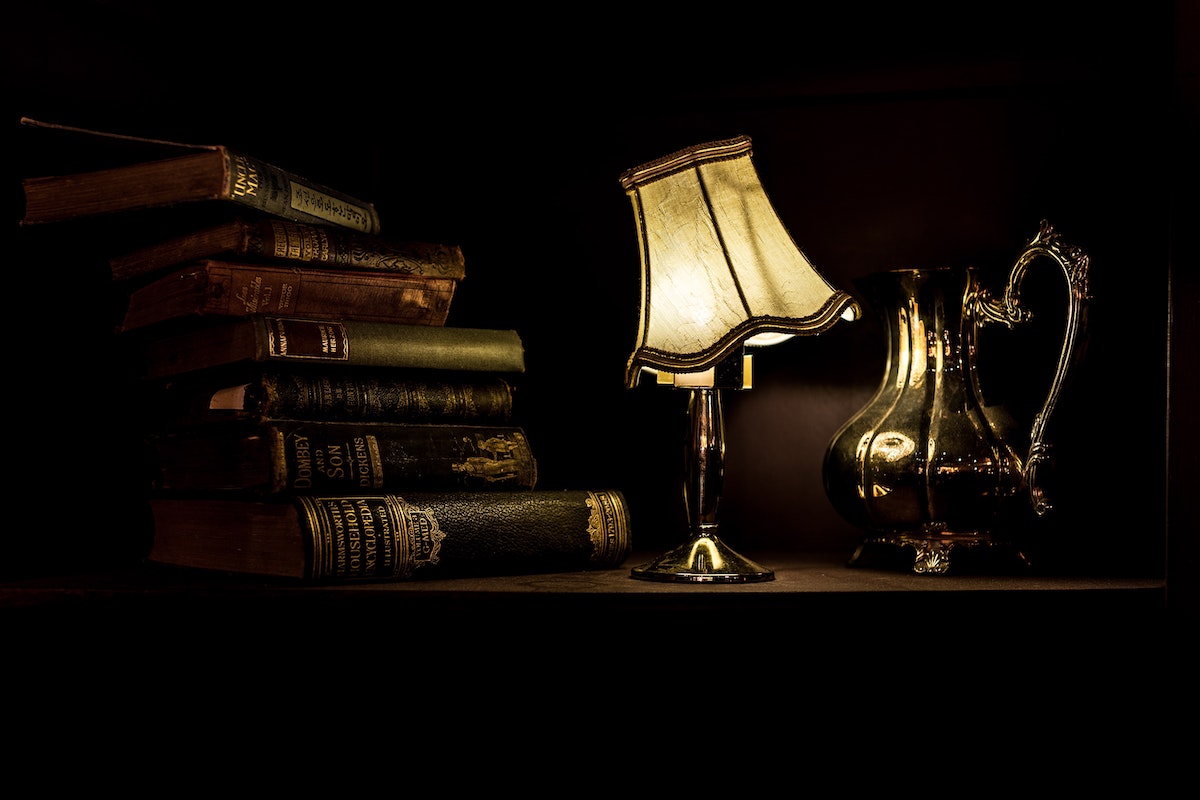

Books

On the Study of Great Books

Great books require intelligence and judgment, and the exploration of sometimes quite fundamental disagreement, from the outset.

Anyone familiar with Australian universities will recognize the opportunistic hype produced by their marketing departments and distilled in titillating slogans like: “Create Change,” “Life Impact,” “Research with Impact,” “Make Change—Change Your Life, Change the World,” “A University for the 21st Century,” “The University that Makes a Difference.” The problem with this is not just the fatuous hubris, it is the open betrayal of the ideals of liberal education.

Compare the slogans listed above with the proverbs that still adorn the archaic coats-of-arms of some of the nation’s universities. Another representative sample: Sub Cruce Lumen (“Light Under the Cross”), Scientia Manu et Mente (“Knowledge by Hand and Mind”), Sidere Mens Eadem Mutate (“The Stars Change, The Mind Remains the Same”), Ancora Imparo (“I am Still Learning”). Where the new slogans are dominated by the images of change and impact, generating a sensation of hectic and thrilling novelty, the older proverbs are sober and modest, emphasising the patient and hard-won acquisition of learning and enlightenment, and suggest that a university education is more concerned with what endures than with what changes.

The slogans capture the tenor of the 21st century university, which has become dominated by the commercial priorities of mass undergraduate vocational training in support of an elite layer of specialised research, priorities mandated by governments and demanded by an international market. Still, there remain some nooks of the university—secreted in the humanities and in science schools, or in an older professional discipline like law—which offer sanctuary to scholars and students who are un-preoccupied, so far as circumstances allow, with their prospects for commercial rewards, popular flattery, and professional prestige. Their reward is one of the mind and spirit, what the political philosopher Michael Oakeshott described as an initiation into a “civilized inheritance” of a “world of meanings and understandings,” a world comprised of languages, literary and other artistic creations, philosophical arguments, scientific theories, historical writings, and theological and political reflection, among other things—and not just any of these, but the very best of them.

The writings which make up this inheritance are often referred to as the “great books.” Some American universities and colleges include a significant selection of the great books as a required component of their undergraduate curriculum. Others offer a standalone degree or certificate devoted entirely to the study of the great books. That is the model followed recently in Australia by a private philanthropic body, the Ramsay Centre for Western Civilization, which is funding the establishment of a degree in Western Civilization, based on the great books, at selected Australian universities.

What follows is advice I would offer to any student with the good fortune to study such a course. You enjoy a remarkable opportunity—afforded inside what Oakeshott called “the interim,” a sunny recess between the sheltered world of childhood and adolescence, and the onerous responsibilities of adulthood—to enjoy without distraction an induction into a great inheritance. It is unlikely you will get it again. I hope the thoughts I have assembled here will help you make the most of your experience. They are not exhaustive and they are not gospel. You can judge their value for yourself as you pursue your studies.

Beware shortcuts

In any university curriculum, there are broadly two kinds of writings you may be asked to study and assess. There are those whose importance is instrumental—they exist for a clearly limited purpose and their value is exhausted by their success in fulfilling that purpose, which is normally to impart information, or to give instruction in a practical skill. Such texts are readily substitutable. If one fulfils the same purpose better than another, it can and should replace it, and the original can be discarded. Because of this, and the rapidly changing world of information and skill thus served, these texts date badly. They are the most common kinds of writings you find in the modern university, and in vocational and professional courses they comprise nearly all your reading.

By contrast, the value of the great books cannot be measured in this way. The value of Homer, Plato, the Bible, Shakespeare, or Dickens cannot be captured in the concepts of information and skill. They serve no purpose beyond themselves and consequently they resist substitution. Nor are they vulnerable to being outmoded by the shifting sands of changing purposes and interests, new technologies, and the like. So long as one remains interested in the most basic questions of what it is to be human, they remain “relevant.”

The first kind of text is of course perfectly appropriate for some subjects. A textbook of contract law or fruit fly genetics is a summary of the field, and usually adequate not only for exams, but—applied and refined through actual practice as a lawyer or scientist—for much of your professional life. Significant amounts of what is central to such subjects can be rote learned from these books. The subject matter can be more or less mechanically assessed with black-and-white answers. Intelligent students will of course want to ask deeper questions, questions which require the exercise of one’s own creative intelligence and judgment, and which admit of more than one arguable treatment. But the capacity to do this profitably matures with one’s grasp of the agreed fundamentals of the subject, and typically comes later in one’s learning.

By contrast, there is an important sense in which the great books resist précis, and little or nothing of value can be acquired from them by rote learning. I can of course summarise the plot of King Lear. That is fine for someone going on Mastermind with Shakespeare as their special subject. But to remain at this level is just to miss most of the play. Great books require intelligence and judgment, and the exploration of sometimes quite fundamental disagreement, from the outset. You cannot simply take an agreed body of doctrine or knowledge for granted and memorise it, the way you can and must in law or science.

There are limits, of course—some readings and ideas and arguments are clearly better than others—but for a significant range of discussion there is no agreed body of knowledge, but rather on-going disagreement and debate. You must make your own way within that discussion, reaching your own conclusions, making them your conclusions—including, perhaps especially, conclusions (or working assumptions) about matters foundational to the genre or the discipline—through the seriousness and quality of your own attention and thought. As Oakeshott puts it, you are not being initiated into a craft or religion, catechised in a doctrine you must accept as a condition of membership, but invited to join an ancient and on-going conversation (one in which people sometimes yell at one another, as can happen in life). No one can tell you your place in that conversation.

In consequence of all this, make it a golden rule with the great books always to go to the original text. Accept no substitutes. This rules out not only explicit cribs like reference books, Cliff’s Notes, and Wikipedia, but also textbooks, websites, movies, and YouTube videos. There is no drive-thru enlightenment. I am over-stating the case a bit here to make the point. There are useful adjuncts (and film is of course a legitimate object of study itself) but their value is distinctly limited and they must always take a second place to the texts they serve.

Beware promises of abstract skills

There are courses and books that offer abstract skills in the place of concrete study of the great books, or more generally, that offer form without content. In particular, universities often offer courses in “how to think” (perhaps called “Critical Reasoning”) that make a false promise of reducing thought to a trainable, semi-formal technique, separable from, but applicable to, any particular content. This is another short cut. Serious thought is not separable from content in this way. You cannot learn to think about X without learning about X, which means reading those works which embody the deepest reflection on X. To assume otherwise is a recipe for consigning yourself to ignorance and insularity.

Reference books and textbooks, even some of the methods taught in critical thinking courses, can sometimes be helpful, but they are no substitute for the original great books as your main focus. Struggle with them, and come to terms with them, even if the terms are sometimes ones of temporary or partial defeat. Patience and persistence bear fruit.

Don’t fall for the “academic fallacy”

The “academic fallacy” is my name for the idea that the most important reading is the highly specialised type found in academic journals. This is a very common danger in the modern university, which, being heavily invested in “research,” exerts unspoken but strong de facto pressure on faculty to treat undergraduate curricula in non-vocational subjects as prolegomena to postgraduate study. Courses are less a general education for all than a kind of filter for identifying promising talent for advanced research.

So reading lists are full of abstruse, specialised articles selected from academic journals. Most of these articles will probably have been published within the last 20 years. Such secondary literature has its place in postgraduate study, but it can be a serious trap for the undergraduate. It tends to be narrowly focussed to the point of pedantry and often vulnerable to fads that pass quickly. It closes the mind prematurely on certain modes of reading and thought, certain assumptions about what the right questions are, what the right methods are, and so on. Mistaken, damagingly partial and even vulgar and ruinous assumptions can sometimes come to dominate parts of an academic discipline in particular times and places. For example, the assumption that science (as modelled by the hard sciences like physics) is the ideal, or even the only genuine, form of human understanding, to which all academic disciplines should aspire. Or the opposing view that science—or literature—necessarily reflects only the point of view of the people who created it (white European males) and that it serves only their interests. This is not to say there is nothing at all to learn from these modes of study, only that if they overbear all others then the great books are being grossly oversimplified, when one of their chief characteristics is their multi-faceted complexity.

As a general rule, the great books, especially those of creative literature, are great because of the depth and shrewdness of their attention to human life. Our own thought must centrally involve appeal to life, and if we are wise, we will not rely merely on our own paltry stock of observation, but also that accumulated observation which has been passed down to us in literature. By contrast, much specialised academic scholarship tends to a high degree of philosophical abstraction (even when the discipline is not philosophy) whose relation to life is often oblique and obscure. That abstraction is an inevitable and important part of thought, and it has a legitimate place in the study of the great books. But if the books themselves are treated as answerable to these abstractions, then things are the wrong way about, and our understanding of both suffers. Even great books of philosophy or theology—which traffic by their nature in formidable abstractions—are importantly beholden to this attention to life if they are not to go badly astray.

Let the books speak

I have just warned against abstract ideas taking over from the text. But it is a hard warning to heed in practice and we nearly all sin against it. There is no reading a book without bringing some preconceptions to it, good or bad. But there is a world of difference between reading that allows the book to challenge those preconceptions and reading that does not. The latter treats the book with condescension, or even contempt.

Great books, we might say, are not confinable to ideology. The power to disrupt our assumptions is one of the things that makes them great. But one must tread carefully with this. In academic literary studies of the last 40 years or so there has been much talk of texts as disruptive, transgressive, and so on. But I am not talking about contrariness or rebellion for their own sakes. It is not about setting out to shock, to épater le bourgeois. It is not (or not necessarily) to be for or against any established order. One often hears the word “critical” used as an adjective to describe some fields of academic studies, e.g., “critical X studies” (as if other fields were uncritical). Too often it means merely to be against when really it should mean to be discriminating. Worse, sometimes it signals an expectation of subscribing to (and conscripting the text and reader into the service of) an ideology.

By contrast, proper attention to the great books cultivates an independence of judgment you should jealously guard. It is no contradiction to say it also cultivates a certain humility, a wish to learn from what better judges than ourselves have seen and thought and said. This is why you cannot replace the great texts with the study of the ephemera of popular culture. Such study can be intelligent and important (in the work of an author whose mind was cultivated partly by the great books, such as George Orwell), but these objects of study typically have limited power to free you from bad ideas. This is one reason such forms of study often tend to be highly ideological. The study of the great books, on the other hand, can provide intellectual liberation; the texts themselves can rescue you from the influence of a lazy or “activist” teacher.

To keep ideology at bay, it is a good habit to read the great books unhindered by an eagle eye on contemporary debates and relevance. This has its place, but as a dominant mode of reading it encourages anachronism and an instrumental attitude to texts as resources to be plundered and prostituted in the service of an alien purpose. To do their work, these books take us away from our own time, our own familiar (perhaps so familiar as to be unnoticed) assumptions and ways of seeing, and introduce us to times and places—worlds—very different from our own. They can only do that if they are not smothered from the outset by the zeitgeist. It is an irony that, through such a foreign imaginative adventure, we may eventually come to understand our own time and place better. Sometimes understanding comes with the perspective of distance. We are too close to our own milieu to be sure what of it will last, or what its deepest problems are, let alone their solutions.

Keep your distance

“Don’t assume you know everything” is advice that seems so obvious as to be unnecessary. Less obviously, one also needs to learn not to assume one’s teachers—or the current “big names”—know everything. Admiration is a natural and warm human quality, so long as it is kept in check. Honour and praise those you admire. Feel free even to become a protégé. But avoid becoming a disciple. A certain distance is always good.

Relatedly, don’t dismiss what you have not read. Or what you don’t understand. If a significant number of thinkers now or in the past have found value in a work, assume there is probably something in it. Perhaps put it aside and come back to it later. Or ask someone to help explain it to you. None of this means you have to show patience to barefaced bilge, but don’t be too quick to assume that that is what you are dealing with. Equally, just as you should not reject a book or thinker without reading them, do not admire a work without reading it. Mechanical deference to the great books does them no service. It circulates a bad odour of snobbery and dishonesty around the whole enterprise of teaching them.

That said, don’t be intimidated or embarrassed by the charge of elitism. Historically, many of the great works were genuinely popular. The Homeric sagas likely began as dramatic oral traditions, as did much of the Bible, which for a long time after it was written down was read aloud to the unlettered in synagogues and churches. The plays of Shakespeare attracted the city crowds of Elizabethan London as cinemas do today. When the works of Shakespeare, Austen, or Dickens are adapted for the cinema or television they reach a popular audience, certainly one much wider than a mere academic caste. Thus, potentially at least, the great books can belong to a democratic culture. Elitism is bad when it takes the form of excluding some people who have the aptitude and interest to read the great books, but it is not elitist—in fact it is the opposite of elitism, it is inclusiveness—to teach the great books to anyone willing and able to learn, be they middle-class university students or the homeless and prison inmates. What matters is not who you teach but what you teach.

Learn another language

A new language is a ticket to a new universe. If you have a gift here, exploit it. Clive James, the great Australian polymath, said he never regretted the time spent in the Cambridge University language laboratories, and on continental trips, that meant he never finished his PhD. In return he got the mastery of several European languages. A highly profitable exchange.

Don’t shirk technicality

If your field of study or interest at some point requires mastery of an exact or technical study—something from science or mathematics or logic—then do not shy away from the hard work required. If it is beyond you, there is no shame in the honest admission of defeat (that goes for learning a language too). But there is shame in pretending to an understanding or expertise you lack, concealing your ignorance behind bluster, or trying to circumvent it by various dodges. Again, take no short cuts.

Embrace the seclusion of a great book’s education

Seclusion from what? From the pressures of the “real world.” Two threats loom here, both already touched upon.

One is to study the books merely from a mercenary or at least a vocational motive. Study of the great books is unlikely to bring commercial success. But you do want to be able to earn a living at the end of your university education, and there is nothing wrong with that. The study of the great books makes little in the way of a direct contribution to that goal. But, at least in developed economies, there is no need to dismiss a great book’s educational value on this account. If you are intelligent enough to study such a course with profit you are intelligent enough to find a decent job at the end of it—and employers will recognize your merit, even if they are philistines. Your study of the great books requires shelter from the business of getting on in the world, but it does not demand a vow of wholesale renunciation.

The more likely worldly temptation is that of political crusades. It is best to avoid subjects that are heavily freighted with ideological and activist goals. The point here is not whether these causes are good or bad but that activism is not education; even in service of the noblest cause, and conducted by the most principled practitioners (and will these conditions be satisfied?), it necessarily coarsens understanding on account of the concessions, adaptations, and abridgments that are necessitated by the exigencies of political warfare. The pressure for this is inescapable, typically inclined to multiply, and—if no factor counter-acts it—to metastasize into distortion and, eventually, outright lies. This can only corrupt thoughtful study.

This is not at all to say you should not be involved in such causes. It is just to say that politics is one thing and education another, and the latter cannot do its work if it is in thrall to the former. You pass from the street-march across the threshold of the seminar room to the calm and patient consideration of the works under study. The slogan and the chant, essentially instruments of intimidation, give way to reasoned argument and close attention to other views; clamour and threats yield to civility and collegiality; rhetoric to honest discourse; conflict and the search for advantage to the common goal of understanding; victory and conversion to mutual enlightenment; debate and polemic—however scholarly and sophisticated—to what, following Oakeshott, I have already called conversation. This does not mean a sacrifice of principles and conviction to some sort of dilettantism or antiquarianism. It does not mean the absence of sharp and sometimes heated disagreement, though it does mean keeping this within limits that serve the ideal of a community of scholars seeking understanding.

That limit is not absolute: a student or a scholar remains a human being and peace is not to be pursued at all costs. Sometimes the world will breach the wall of seclusion and sometimes it is right that it should (and sometimes it is not). But if it knocks the whole wall down, then it demolishes the distinctive good that liberal education exists to offer and which it is hard to find elsewhere. The undergraduate is young and on the threshold of their life. Few will become professional scholars (although most, I hope, will be life-long readers and thinkers). There is space enough outside the seminar room and time enough in a life for the business (and busy-ness) of the world. Let this refuge from that world be what it is, and it will repay you in riches.

Remember that persistence is a virtue

You need not exhaust yourself in a super-load of hard work, consuming every evening and weekend. Steady, regular, and moderate habits are required: the tortoise not the hare, the marathon not the sprint. However gifted you are, don’t assume intelligence is enough. Sudden, concentrated bursts of energy may get you through an exam, but they will not bestow depth of appreciation and understanding. If you neglect these texts, if you trifle with them, they will punish you.

Be conservative—and liberal

It would be silly to think that the great books of the traditional Western canon are the only books worth reading. For a start, as well as great books there are also excellent books, and then (let’s call them) very good books, and these are worth reading too, especially as your interest in a topic develops and becomes more specialized. Another reason is that decisions about what gets into the canon were not made in heaven, but were, and are, the decisions of particular people in particular times and places, so those decisions are subject to all sorts of contingencies. This does not mean that the content of the canon is entirely arbitrary and unwarranted, but we should be alert to various influences that affect what gets included and what does not, and be ready to revise.

These days there is a particular concern that the canon unjustly reflects the power and interests of the Western world, and unjustly excludes the works of other civilizations and of other groups within Western civilization. This concern is legitimate. Each generation should consider the canon in the light of its own conditions (without thereby making it merely a function of those conditions). This does not mean taking a wrecking ball to the canon, as some would do. The wrecking ball attitude tends to go with the crudely reductive theory that books and ideas (and everything else) are just about power—weapons in the conflict between various social strata, the rulers and the dominated. It is ultimately a nihilistic position. The truth is that reform is best conducted by those who love that which they reform, for they are the ones who truly have its best interests at heart.

That love makes for an inherently conservative enterprise in the best sense of that word. But what gets conserved is not so much particular texts (though it is true of some—Homer, the Bible, and Shakespeare most obviously—that it is very hard to see them ever being displaced) as the continuity of the conversation, and the kind of spirit in which it is conducted. That spirit is, or should be, liberal in the best sense of the word: magnanimous, generous, open-minded, and expansive. We would be unfaithful to that spirit if we regarded the canon as wholly closed and unchanging, and unfaithful to the conversation if we did not allow it to take new and unexpected turns, albeit without losing touch with what has gone before. This liberal spirit will welcome the inclusion of new, neglected and previously foreign works, wherever they are found. Perhaps the guiding thought here is that expressed by the Roman playwright Terence in his words “nothing human is alien to me.”

Take delight in your studies

Make time each day to read just for pleasure and interest even if you can manage only an hour or even half-an-hour. Though your formal study will sometimes rightly require you to read material you will not always enjoy, there is no point to making this kind of study a burden as a whole. The most underestimated advice is just to enjoy your learning. That pleasure may rise to a lasting love.

Value your education

If you have the opportunity to study these books in the leisure and energy of your youth, then carpe diem! You enjoy a privilege few will ever know. Just how great a privilege may be measured by how some human beings have turned to what they have learned from such an education to seek a sustaining meaning—a refreshment of the spirit—under conditions designed to crush the spirit. Consider this passage (an example of a kind of story I used to tell my students whenever they complained about essay deadlines). It is from Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago, his titanic account of Stalin’s system of prison camps for political dissidents in the Soviet Union.

At the Samarka Camp in 1946 a group of intellectuals had reached the very brink of death: They were worn down by hunger, cold, and work beyond their powers. And they were even deprived of sleep. They had nowhere to lie down. Dugout barracks had not yet been built. Did they go and steal? Or squeal? Or whimper about their ruined lives? No! Foreseeing the approach of death in days rather than weeks, here is how they spent their last sleepless leisure, sitting up against the wall: Timofeyev-Ressovsky gathered them into a “seminar,” and they hastened to share with one another what one of them knew and the others did not—they delivered their last lectures to each other. Father Savely—spoke of “unshameful death,” a priest academician—about patristics, one of the Uniate fathers—about something in the area of dogmatics and canonical writings, an electrical engineer—on the principles of the energetics of the future, and a Leningrad economist—on how the effort to create principles of Soviet economics had failed for lack of new ideas. Timofeyev-Ressovsky himself talked about the principles of microphysics. From one session to the next participants were missing—they were already in the morgue.

These people died making an effort to preserve civilization in the face of the determination to exterminate it. In your study you become a participant in that same effort at transmitting and renewing an essential part of the human heritage.

Andrew Gleeson is a writer and erstwhile philosopher. He lives in Adelaide, Australia.