Activism

Accessibility, Ableism, and the Decline of Excellence

Differences that benefit the individual (beauty, intelligence, wealth, initiative) can only be understood as unfair privileges, while differences that do not redound to the individual’s benefit can only be made into disabilities which ultimately perpetuate inequity.

For many years, colleges and universities have observed the Americans with Disabilities Act by finding alternate ways for students with disabilities to meet course requirements. For example, a blind student might be accommodated by allowing a university representative to orally read the student questions from a written exam. A student with limited mobility might be allowed some extra time in getting from one class to another. More recently, many universities have expanded accommodations to cover conditions that might have been ignored in the recent past: today, students who can document Attention Deficit Disorder are routinely offered extra time in taking exams.

One example of the rapidly changing institutional culture regarding students with disabilities is a new service provided by Blackboard, which is perhaps the most common software platform in American colleges for delivering course content. Through Blackboard, professors post required readings and assignments, grade student work, and even facilitate online discussions among members of the class. This fall, the university at which I teach implemented an additional service offered by Blackboard that is called “Ally.” Blackboard Ally is a tool built into the software that alerts the professor in the case that any material posted for the course may be less than perfectly “accessible” for students. Next to each document posted for the course, a small gauge or dial is shown: colored green, yellow, or red, the software judges the “accessibility” of each file. I post mostly Microsoft Word documents and .pdf files for my courses: sometimes these would be deemed green, sometimes red. As I don’t have the technical knowledge to know which disability my Word files are disadvantaging (or the time or knowledge to make them more “accessible”) I generally ignore the feedback from Blackboard Ally.

But my university made it clear that they expect full compliance from faculty. They rolled out a campaign stating that “Green is the goal!” In other words, all material posted for classes should have a green dial. The very name of Blackboard Ally exerts a kind of rhetorical force that demands compliance. Most Americans under 40 associate the word ally with the LGBT movement (the Second World War might as well have occurred in the Dark Ages). In LGBT discourse, to be an ally is to offer an affirmation of the LGBT community and criticism of the marginalization of its members. Of course, given the far-left culture on campus, to be anything other than an ally is to be aligned with the power of hate and bigotry—something that ensures exile from the university community. No one on campus wants to not be an ally. And so, we see the aggression in Blackboard’s gambit: to resist Blackboard Ally is to be a hater.

Ableism and the Inclusion Agenda

As a professor, I am generally happy to provide reasonable accommodations to students in need. I agree that it is important to make the university as “inclusive” as possible, assuming that the accommodations in question don’t undermine the university in fulfilling its larger objectives: providing excellent education and producing new knowledge in a context that holds high standards for both student and faculty achievement. Unfortunately, readers who are familiar with campus nuttiness like safe zones, trigger warnings, microaggressions, and the ongoing Title IX racket, will not be surprised to learn that many of the standards that remain in higher education are now being sacrificed on the altar of “accessibility.”

The list of “disabilities” that warrant accommodations continues to expand and now the sheer number of students seeking these course adjustments is so high that many voices in the faculty and administration are calling for a radical reimagining of the process for determining which conditions warrant accommodation and what accommodations will be made. In the name of fighting “ableism,” ideologues are pushing for new institutional procedures that undermine the universities’ pursuit of intellectual excellence. In large part, this is a purposeful attack: at the conceptual level, excellence and competence are increasingly understood as by-products of unearned privilege and the marginalization of historically oppressed groups.

Before providing further examples of how this agenda is advanced through campus initiatives, a few words on “ableism” and “accessibility” are in order. The former is a term that was invented to advance a criticism of standards that some allege to be overly demanding. Not coincidentally, “ableism” echoes all the other “-isms” we are told are so pervasive in American society: racism, sexism, imperialism, ethnocentrism, and so on. Anti-ableism activists assert that our society and institutions are structured in ways that privilege those without disabilities. They argue that our professional and public lives are easier to navigate if one is able-bodied and of sound mind. And that is undeniable: life is easier for able-bodied people. The anti-ableist reasoning says that the advantages of the able-bodied are unfair. Perhaps that is true: in some cosmic sense, it is unfair that one might be born with epilepsy or with a club foot. But it is here that the anti-ableist goes a step further. Many people would argue that life is harder for people with disabilities, and that is perhaps unfair, but they would also recognize that life is unfair and that there are limitations to the ways that society can ameliorate the difficulties faced by the disabled. In contrast, the anti-ableist argues that the parts of society that are still easier for the able-bodied person must be re-structured. They aren’t talking about installing ramps for wheelchairs to provide access to public buildings.

“Accessibility,” as defined by campus activists, is a consideration of the relative ease or difficulty of completing tasks and achieving goals. Thus, if one’s Attention Deficit Disorder ensures that a student misses critical information during lecture that will later appear on an exam, the professor must find alternate means of delivering that information. Otherwise, the course would be deemed “inaccessible,” which in the highly ideological prism of campus politics is tantamount to saying that the course is a form of oppression that accords “privilege” to the students without disabilities. Never mind that as a professor, I have no way of knowing which information a student may have missed. Traditionally, questions from students during class would be an indirect way of assessing their grasp of course content. But now, the onus increasingly lies with the professor to discern the ways that the course design is disadvantaging students. Further, the traditional, direct means of assessing student mastery of course content—exams—are increasingly understood as a way of maintaining privilege and enacting bias. Imagine the task the instructor is now burdened with to achieve an “accessible” class environment: not only must one be aware of the broadening range of “disabilities” that are possible, one must know how to identify them all and recognize the ways that the course structure limits each student’s potential for success.

Accessibility, in the traditional sense, is a virtue to which a democratic, pluralistic society should aspire. But taken to an extreme—an explicit attempt to re-design institutional procedures and culture at large in such a way that a person with any limiting condition faces no additional challenge—accessibility represents an aggressive pursuit of a perfect equality of outcome. In this ideal world, not only can everyone succeed, everyone will succeed: any failure to meet a goal can conceivably be due to some unfair disadvantage (diagnosed or otherwise). The world imagined by anti-ableists is one in which everyone achieves excellence in all competitive pursuits. And of course, if everyone is excellent, then no one is.

Institutionalizing Mediocrity

As it stands currently, the typical process for accommodating students with disabilities goes something like this: in the first weeks of the semester, the student notifies the Office of Disability Services that he needs adjustments to a course’s requirements due to a disability. After providing medical documentation of the condition in question, the university determines whether and which accommodations must be made to a course in order to give the student a fair chance at success. The professor is then informed of which adjustments he should make in order to accommodate the student. Although this system is not without problems, in general it is a fair and vital service for students. Nevertheless, there are signs that this process will soon undergo a radical revision, in much the same way that Title IX was recently weaponized to advance ideological commitments.

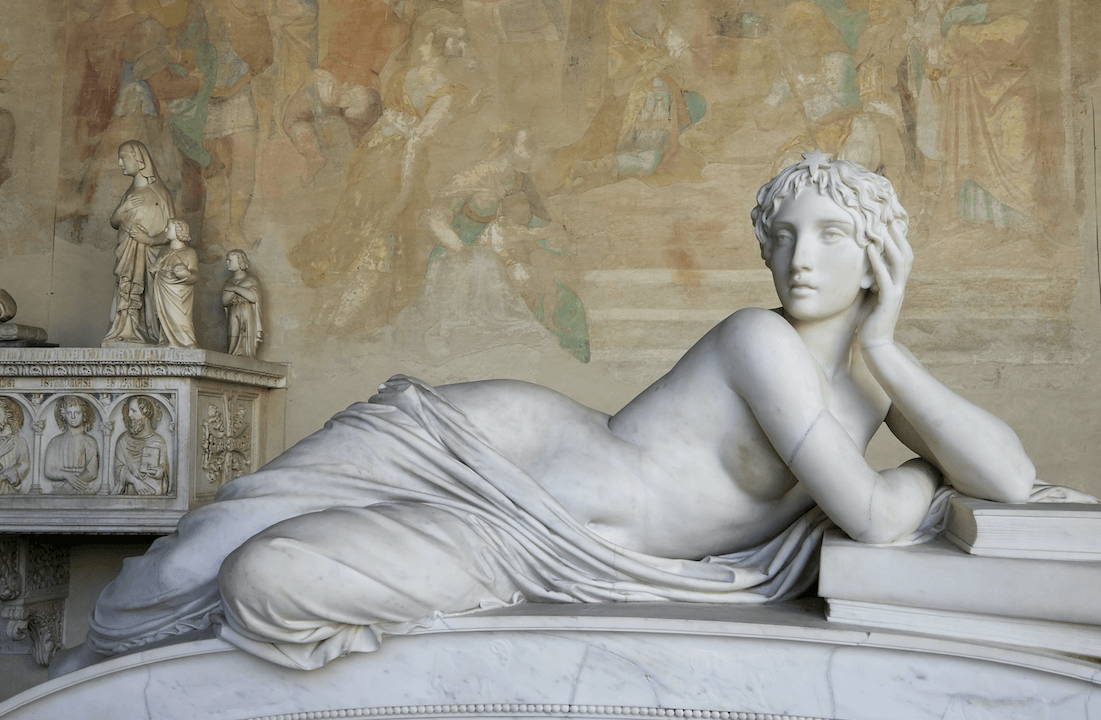

At our annual faculty meeting to begin the fall semester, my university sent representatives from the Office of Disability Services to emphasize the importance of satisfying Blackboard Ally’s preferences for the accessibility of course materials. As part of the presentation, we were shown the following image, which some readers may have seen circulating online:

With the image displayed on the whiteboard, the presenter explained to us that equity is the goal of Blackboard Ally, and proceeded to tell us that if a course requirement can be modified to make it easier for a person with a particular disability to achieve, the adjustment should be made—whether or not there is a student with that disability in the course. Further, we were warned that if any assignments or course requirements could not be adapted to make them achievable and accessible for people with a(ny) disability, then the instructor should not have that requirement or give that assignment. As an example of how far-reaching these new guidelines would be if fully implemented, I am aware of an art instructor who tests students on their abilities to discern certain shades and tints of color. Obviously, this task can’t really be adapted for a person who is colorblind. Thus, such an assignment would now be evidence that the course is an inaccessible one—even if no one in the course is colorblind.

In a sane educational environment, we would still teach and require art students to master the subtle variations in color schemes, and if a colorblind student were to take the course, we would offer a different assignment so that the student need not forfeit the credit this component of the course. The new order advanced by Blackboard Ally would ultimately render the current procedure for addressing disabilities obsolete: if everything in the course is designed so that no one with any disability would face any difficulty in achieving success, then disabled students would no longer need to offer medical documentation of disabilities and negotiate accommodations with professors. That scenario—where every possible need is fully anticipated and fully accommodated—is precisely what anti-ableists imagine when they envision the fully “accessible” society.

When the presenter completed her presentation, faculty were allowed to ask questions. It was heartening that as my colleagues began to grasp the scope of these new guidelines, quite a few voiced some resistance. I joined in to ask a question of my own. Pointing at the image above, I said “I notice that there aren’t any visible adjustments made in the baseball game the boys are watching. Presumably, some players are taller than others. Why aren’t the shorter ones on boxes? What about the ones who are slower than the others? How will we ensure that the batters with more upper body strength don’t have an advantage? Could you talk a little about why there are no adjustments on the field?” We live in Houston, and the town loves Jose Altuve, the diminutive slugger for the Astros. I continued: “Why doesn’t Altuve get to stand on a box?”

Surprisingly, the speaker didn’t understand what I was getting at—she literally didn’t understand the question, so I stopped pushing because I’m sure the answer would have been as troubling as the picture itself. But to answer it accurately would illuminate some troubling assumptions at work in higher education. The athletes don’t get these accommodations because the game they play is a competitive one. The team that can maximize their strengths and abilities wins the game. We wouldn’t want to achieve equity and accessibility in sports, even if we could: every game would end in a tie. And while it’s true that in such a scenario every player would get to raise a trophy at the end of the season, what is lost? In a word, excellence. For thousands of years, humans have devised contests that require the demonstration of excellence. Excellence and striving are what make victory and achievement meaningful, and in failure, it is the pursuit of excellence that allows a loser to maintain some nobility in defeat.

In telling professors that we need to meet the vision of equity as demonstrated in the picture above, universities indicate that they understand academics not as a competitive pursuit of excellence, but rather as a kind of spectatorship, and perhaps, as entertainment. In contrast to the activity of the players on the field, our students passively watch their “education” unfold. If the new vision of accessibility continues to gain ground, no student will have to worry about the prospect of failure: total accessibility means universal success. But the success that is “won” is one defined by a perfect mediocrity—an outcome that critics of democracy have lamented for time immemorial.

A few tragic outcomes can extend from this type of “achievement.” First, truly excellent students understand that their accomplishment isn’t terribly meaningful. They know they never got to achieve excellence; not because they can’t achieve it, but because they weren’t allowed to: the entire curriculum was designed to mitigate against any skill or acumen that might “privilege” them over their peers. Indeed, many weaker students who “succeed” are also aware of the mediocrity of collegiate study, ensuring that they value their achievement less. But the worst possibility is that mediocre students who “succeed” assume that their success indicates their excellence: an obliviousness to one’s own limitations can come with bitter consequences. Ultimately, such students are deprived of confronting what they do not know—they remain unaware of their ignorance, and thus, see no reason to strive for personal improvement. The fact that universities today seem to view education as more akin to watching a baseball game than participating in a competitive athletic competition is a great loss for our society. It’s heartbreaking: we have less respect for our work than our games.

Celebrating and Erasing Diversity

Blackboard Ally may seem a pretty thin reed to support the claim that accessibility and inclusivity are a threat to American universities and society at large. But don’t be fooled: there are many initiatives being advanced at all levels of the university—administration, staff, faculty, and students—that aim at ensuring universal access, universal success, and universal mediocrity. This past semester I observed the presentation of a graduate student who was being considered for a professorship. Her presentation was on “neurodiversity” in students and how to accommodate it in educational settings. By “neurodiversity,” she referred to conditions like autism, depression, anxiety, and mood disorders.

As her presentation unfolded, it became clear that all of these require some preemptive accommodation. For example, she suggested that students with disabilities shouldn’t be required to offer medical documentation because not everyone has equal access to healthcare. Further, instructors should make class more accessible by not penalizing students for regularly being late to class: anxiety disorders may require some students to take a circuitous route to class to avoid crowds. Never mind that late arrivals distract everyone in the class, and never mind that looking the other way on regular tardiness sends a message to other students that class simply isn’t that important. As an aside, the presenter lamented that Google Maps undermines “neurodiversity” because it gives you routes that assume that you want to know the fastest way from one place to another (after all, a person with anxiety may prefer a less direct route). One is left to wonder: what would Google Maps look like if it were built without the assumption that users primarily value time efficiency in considering how to move about space?

On the whole, the term neurodiversity nicely indicates the mediocrity that advocates of radical accessibility pursue. It recognizes that people have cognitive differences, but in trying to accommodate difference they inevitably read difference as disability that requires totalizing adjustments. This denigrates the potential of people who face various challenges—it handicaps their chances at true excellence. In the end, difference is all there is. Insofar as anyone is an “individual” at all, we all have differences and limitations with which we must contend. But as ideology, radical inclusivity fetishizes these endless differences. Differences that benefit the individual (beauty, intelligence, wealth, initiative) can only be understood as unfair privileges, while differences that do not redound to the individual’s benefit can only be made into disabilities which ultimately perpetuate inequity. As is increasingly the case, any inequity is evidence of injustice. And injustice must be met with accommodation to mitigate the effects of individual differences, which are crassly simplified as unearned privilege or the residue of oppression. Ironically, the intervention to address these differences is a sweeping attempt to manufacture universal success—a success without dignity or excellence, a success that ultimately negates individual differences rather than affirms them. Thus, the advocates of accessibility celebrate diversity as they erase it.

Adam Ellwanger is an associate professor specializing in rhetoric and public discourse at the University of Houston—Downtown. He is a member of Heterodox Academy. This spring, Penn State University Press releases his new book Metanoia: Rhetoric, Authenticity, and the Transformation of the Self. You can contact him at [email protected]

Featured image from BCCampus_News (Flickr)