Art and Culture

Beauty, Equality, and the Problem with Calling Everything 'Sexist'

At the heart of this revolution lies the myth of the “authentic self” – the largely or entirely mutable or malleable “self-realizing” person of indifferent gender.

For the literary critic Katie Roiphe, the male sexual passivity depicted by contemporary male novelists masks a “sexism” that is “wilier and shrewder and harder to smoke out” than that of their literary predecessors. “What comes to mind,” she wrote, “is [Jonathan] Franzen’s description of one of his female characters in The Corrections: ‘Denise at 32 was still beautiful.’ ”

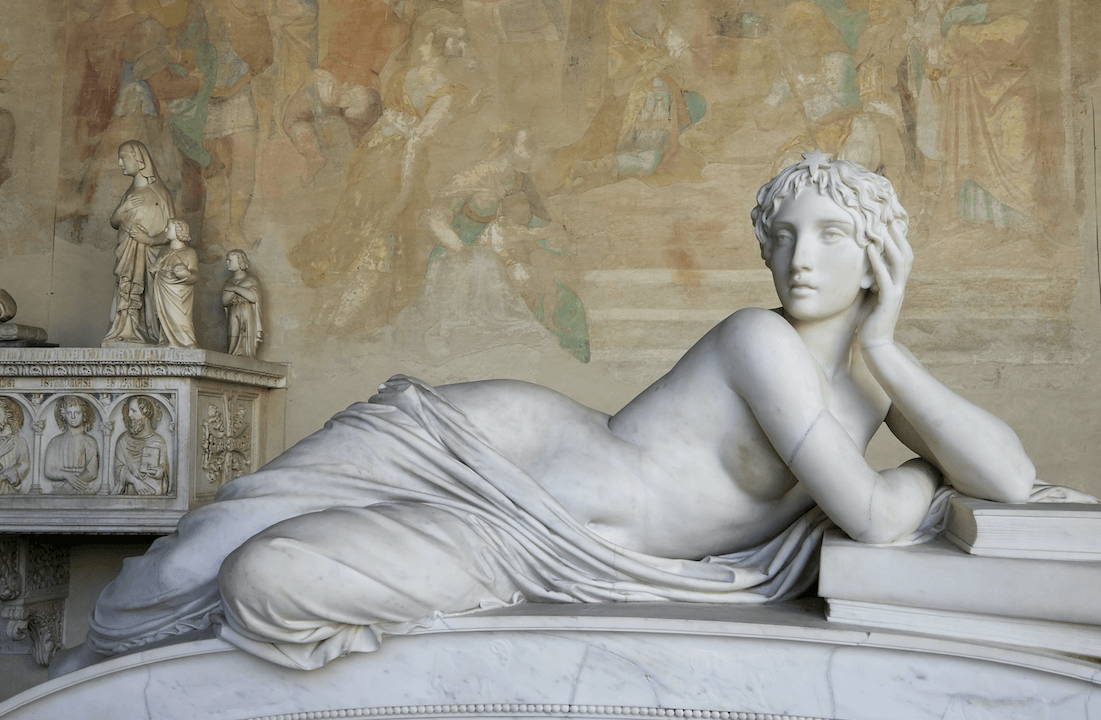

Now, for a man, fictional or real, to say of a woman that she is “still beautiful” at a certain age is without doubt to reveal a crass male sensibility and to express a trite sentiment. But such a statement – an aesthetic judgment, actually – is “sexist” only under the greatly expanded meaning this term has acquired since the revolution in consciousness of the 1960s and 1970s.

At the heart of this revolution lies the myth of the “authentic self” – the largely or entirely mutable or malleable “self-realizing” person of indifferent gender. This myth was propounded by Charles Reich in The Greening of America, Germaine Greer in The Female Eunuch, Theodore Roszak in The Making of a Counter Culture, and other social theorists of the time. It is the intellectual basis on which the process of personal “liberation” and radical cultural and social change that began in the 1960s has proceeded apace since then. And because this myth, thanks to writers like Greer, has also long since been equated or conflated with feminism, anyone who contravenes it can be readily accused of “gendered thinking” or “sexism.”

In line with this myth, we are now required to consider as sexist, not just discriminatory treatment or prejudice based on sex, but any statement that in any way highlights or refers to or implies the existence of any sort of difference between men and women in how they think about or respond to each other and the world at large – including how they experience female beauty. Yet on this last question, as on many others, the differences are profound.

Take the general indifference of men to women’s urge to beautify themselves. This indifference was a source of some amusement to Jane Austen who commented on it with mock portentousness in her novel Northanger Abbey:

". . . for man only can be aware of the insensibility of man towards a new gown. It would be mortifying to the feelings of many ladies could they be made to understand how little the heart of man is affected by what is costly or new in their attire. . . . Woman is fine for her own satisfaction alone. No man will admire her the more, no woman will like her the better for it."

However indifferent they may be to new gowns, men feel it is important to be able to respond to what the novelist Giuseppe di Lampedusa described as “the bugle call of feminine beauty.” In answering this call literarily, Mr. Franzen was guilty, not of sexism, but simply of being or acting like a man, which nobody needs to be told often means behaving gauchely or obliviously toward women. The same is true of former president Barack Obama who in 2013 publicly described Kamala Harris, an old friend of his, as the “best-looking attorney general in the country,” an affectionate and harmless statement to most people but a trip wire for the politically correct, who immediately denounced Mr. Obama on the websites of Salon and the Los Angeles Times.

In this connection, and for clarity’s sake, sexism should also be distinguished from male chauvinism. President Donald Trump, for example, in his personal attitude and behavior toward women is or was what used to be called a male chauvinist pig or MCP (a type of “authentic self” that is now flourishing on college campuses and elsewhere thanks to our society’s abandonment, in the name of equality, of the idea that men should treat women with solicitous respect). But in view of Trump’s record of appointing women to important positions in his business empire, political campaign, and administration, it is hard to see how he (any more than his MCP predecessor Bill Clinton) could be termed a sexist, however politically useful he may have found it to promote such a perception during the 2016 election campaign.

The inconsistency entailed by the broad use of this term is no less apparent than the confusion it has produced. Thus, the complaint Katie Roiphe aired – namely, that the males depicted in novels today lack the quality once described as “manliness” – is by her own standard thoroughly “sexist” in character. Thus, too, it is perfectly okay these days to use a clearly sexist phrase like “chick lit” that mocks or denigrates not just the books that speak to women’s interest in traditional love and romance, and not just the women who write such books, but also the women who read them.

Our contemporary inconsistency in such matters was even more memorably on display twelve years ago in the reaction to a speech given by Lawrence Summers at a conference on “Diversifying the Science & Engineering Workforce” sponsored by the U.S. non-profit National Bureau of Economic Research. Concerning “the very substantial disparities . . . with respect to the presence of women in high-end scientific professions,” Summers suggested that:

"what’s behind all of this is that the largest phenomenon, by far, is the general clash between people’s legitimate family desires and employers’ current desire for high power and high intensity, that in the special case of science and engineering, there are issues of intrinsic aptitude, and particularly of the variability of aptitude, and that those considerations are reinforced by what are in fact lesser factors involving socialization and continuing discrimination."

This was deemed “sexism” even though it was no more an expression of prejudice or discriminatory intent against women than some of Germaine Greer’s assertions in The Female Eunuch were expressions of prejudice or discriminatory intent against men, e.g., that only women, with their “oceanic feeling for the race” and “genius for touching and soothing,” could save mankind from nuclear self-destruction: “If women can supply no counterbalance to the blindness of male drive the aggressive society will run to its lunatic extremes at ever-escalating speed. Who will safeguard the despised animal faculties of compassion, empathy, innocence and sensuality?”

Though part of a plea for “revolution,” these statements invoked entirely traditional – and by today’s standards “sexist” – ideas about the different modes in which men and women tend to engage the world, modes that are by no means mutually exclusive but in which the male and female emphases are quite distinct. But when Mr. Summers tried to discuss the same sort of differences in the same sort of terms, he was pressured to resign as president of Harvard, even though the “high power and high intensity” of his male scientists and engineers was simply another way of describing what Greer called “the blindness of male drive.”

What the Summers episode made clear is that, though it’s okay for someone like Germaine Greer to say that women have a special aptitude for saving mankind from a nuclear war (and has there been a more popular political cliché over the past fifty years than the equation of women with peace?), it’s not okay for a male academic to talk about the flip-side of the same coin: namely, that men have a special aptitude for designing and building the intercontinental ballistic missiles that would be used to destroy mankind in a nuclear war. The merits of such statements aside, it is also clear that it was Mr. Summers who, in line with this discriminatory standard, was objectively a victim of sexism in being forced out of his job.

Such inconsistency (or hypocrisy) is the unavoidable result of trying to preserve the myth of the “authentic self” in the face of recalcitrant reality. Indeed, not even transgender people – who are perhaps the most acutely aware of the differences between men and women and of the anguish these can cause – are permitted to contradict this myth, as the case of the former Olympian Bruce now Caitlyn Jenner shows. For saying, “My brain is much more female than it is male” and talking about how much she likes to put on make-up and dress up, Ms. Jenner was taken to the same ideological woodshed as Lawrence Summers by the journalist Elinor Burkett.

Yet what Ms. Jenner said was entirely in line with the anti-marriage author Jaclyn Geller’s view that, “Since good make-up and skin care products can dramatically improve an individual’s appearance, women who purchase beauty products with the desire to look their best seem to me to be behaving quite reasonably, rather than acting the part of self-hating brainwashed victims.” Indeed, what was Ms. Burkett’s own observation concerning women like herself – that nowadays “most of us feel free to wear skirts and heels on Tuesday and blue jeans on Friday” – but an expression of precisely the same feminine interest in self-adornment that she criticized Ms. Jenner for articulating? And what were her, Ms. Jenner’s, and Ms. Geller’s statements but confirmation of Germaine Greer’s acknowledgement in The Female Eunuch that “Most women would find it hard to abandon any interest in clothes and cosmetics, . . .”?

This was one of Greer’s several other major concessions to the reality of the non-mutability of the sexes – and it is by no means her only point of contact with Jane Austen. But if we have to start calling Germaine Greer a sexist, then it seems to me we’ve got a problem.

This is not an idle point. As the New York Times reported in October 2015 a petition signed by nearly one-thousand people demanded that Cardiff University bar Greer from speaking there because, according to the women’s officer of the students’ union, she had “demonstrated time and time again her misogynistic views towards trans women, including continually ‘misgendering’ trans women and denying the existence of transphobia altogether.”

That Germaine Greer has become the target of politically correct attempts at censorship that put her in the same boat with Barack Obama, Jonathan Franzen, Donald Trump, Lawrence Summers, and Caitlyn Jenner, not to mention such well-known conservatives as Ann Coulter and Charles Murray, shows just how unlimited the potential of this phenomenon is. It also shows that Greer reversed in some way her adherence to the myth of the “authentic self,” observing among other things that “ ‘I don’t think surgery will turn a man into a woman’ ” and telling the Times “that ‘a great many’ women did not dare to say that transgender people ‘don’t look like, sound like, or behave like women.’ ”

This reversal is consistent, one might say, with the inconsistency with which this myth has been promulgated over the past half-century. As we have seen, Greer, as one of the leading champions of the counterculture, appealed at times to an unmistakably pre-counterculture understanding of the differences between men and women – the very differences we were supposed to be in the process of abolishing but which in fact we were merely imagining or pretending no longer really mattered. Many of her ideological successors have followed the same contradictory pattern of validating, directly or indirectly, the enduring differences between men and women in the course of trying to demonstrate or insist that such differences do not or should not exist.

The irony is that this insistence on an impossible psychological or existential congruence – as distinct from legal equality, fair treatment, and a recognition that what may be true in general about the differences between men and women is not necessarily true or true in the same way in any particular case – has actually diminished the contemporary woman’s moral autonomy.

In response to the perceived problem of women being underrepresented in high-end science, for example, professor Eileen Pollack of the University of Michigan suggested that we redecorate “the classrooms and offices in which they might want to study or work” in accordance with the finding that “female students are more interested in enrolling in a computer class if they are shown a classroom (whether virtual or real) decorated not with Star Wars posters, science fiction books, computer parts and tech magazines, but with a more neutral décor – art and nature posters, coffee makers, plants and general-interest magazines.”

Leaving aside the “sexist” assumption of this sort of research – namely, that women, unlike men, are easily beguiled by home-style furnishings and appliances – the idea of tricking women in this way into signing up for science classes reduces them to a species of child. Indeed, one can find a more sophisticated, progressive, and empowering attitude toward women in science in such classic 1950s science-fiction films as It Came from Beneath the Sea and Them!

Ms. Pollack’s suggestion is an example of what the anti-traditional love author Laura Kipnis, in a different context, calls “the return of the ‘delicate flower’ syndrome” and is an indication of just how regressive contemporary attitudes toward women have become. Referencing this regression in the political sphere, the novelist and critic Zoe Heller wrote during the 2016 Democratic primary season that “among [Hillary] Clinton’s feminist supporters, the disheartening tendency to characterize any resistance to her candidacy as either sexist or the product of false consciousness persists”:

"Horrid though it is that men have criticized Clinton’s figure and voice and called her ‘Hellary’ . . . none of these things are very good or grown-up motives for electing her to the highest office in the land. It would be a fine thing to have a woman in the White House. But, really – let’s not put her there because someone once said she had ‘cankles.’"

Heller’s old-fashioned plea – that we choose our political candidates on the non-sexist basis of capability rather than a “gendered” sense of entitlement – seems prescient in light of Trump’s victory in the general election and the fact that 53 percent of white women voted for him even though Mrs. Clinton played the “woman card” for all it was worth. But Ms. Heller’s point is even more significant for another reason: it highlights the limits or backfiring of the strategy of, in sixties’ parlance, “making the personal, political,” in this case the very personal matter of a woman’s sex and physical appearance.

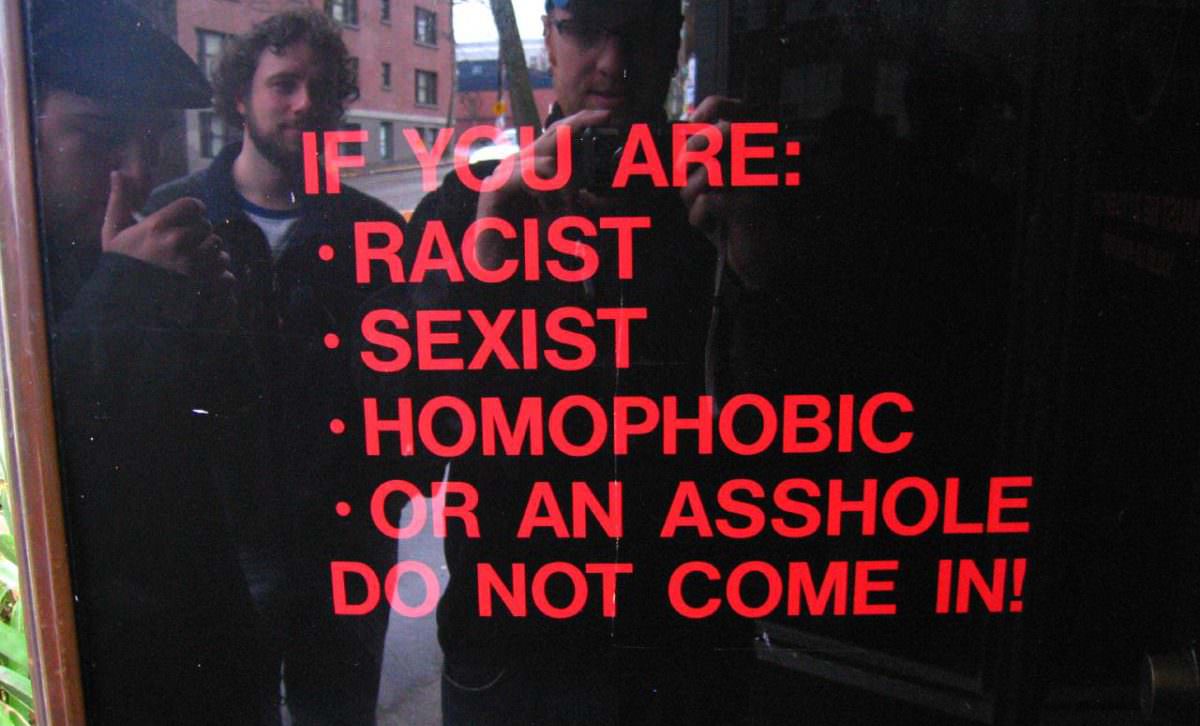

Most of all, Heller’s assessment raises the fundamental cultural issue of how we think about and conduct ourselves in society. “Making the personal political” is an extension or application of the idea championed by Charles Reich and other sixties-era theorists that “the individual self is the only true reality.” And this solipsistic notion is the wellspring of “political correctness,” a phenomenon in which nothing more substantial than personal vanity is transformed into a collective demand, not just for ideological adherence, but for psychological and social regimentation. The premise of this demand is that it is impossible to tolerate the thought that there is somebody somewhere who doesn’t think the same way I do about everything. As the historian Tony Judt wrote, lamenting our having “taken the ‘60s altogether too seriously”: “Why should everything be about me? Are my fixations of significance to the Republic? Do my particular needs by definition speak to broader concerns?”

The answer is yes if one accepts the myth of the “authentic self” and its unforgiving logic. The answer is no if one believes that turning one’s back on a commencement speaker is simply bad manners and ought not to be tolerated, that physically attacking a professor for having invited someone to speak on campus with whom one disagrees is assault and battery and ought to be punished, or that seeing a sexist under every bed or behind every compliment or in the wallpaper is a sign of moral foolishness, not serious thought. Unfortunately, at the moment the “yes” camp continues to hold cultural sway.