Activism

The Sad Truth About ‘Fat Acceptance’

Unfortunately for some activists, gravity wasn’t invented by white settlers.

Last week, self-described queer non-binary “fat sex therapist” Sonalee Rashatwar delivered a two-hour lecture entitled Race as a Body Image Issueat the St. Olaf College Health and Wellness Center in Minnesota. The event was a master class in social justice, at times putting shame to the parodies of the genre that now traffic on social media. In the video, the visibly obese woman asks: “Is it my fatness that causes my high blood pressure—or is it my experience of weight stigma?” In the presentation, which has gone viral, Rashatwar also compared “fatphobia” not only to eugenics (which is itself absurd) but also to “Nazi science,” and declared that “a child cannot consent to being on a diet the same way a child cannot consent to having sex.” Indeed, the very titles of her recurring presentations—including Health is a Social Construct, Decolonizing Sex Positivity, Gender Isn’t Real and Neither Is Health and How Fat Queers the Body—seem like something you’d find on the Twitter feed of satirists such as Titania McGrath or Madeline Seers. Yet Rashatwar can’t be dismissed as just another social-media kook—for she is regularly invited to speak to actual health experts at numerous universities across North America, including, recently, medical students at the University of Texas. The listed speaking fee on her web site is US$5,000. (She also specifies that “travel arrangements should not be made on Sonalee’s behalf by the host organization due to her disability needs.”)

At St. Olaf, Rashatwar began with a Native land acknowledgement—which, as a Canadian, I found odd: Obesity is a huge problem for Indigenous people. In Canada, 37% of reserve-resident First Nations people are obese. In the United States, it is estimated that 60-80% of American Indigenous and Alaska Natives are overweight or obese, and more than 30% are in a diabetic or pre-diabetic state. What allows her to compartmentalize the issues of Indigenous welfare and obesity, I suppose, is her belief that the goal of avoiding extra poundage is a “white supremacist beauty ideal.” She informs audiences that “I come from an exclusively pro-body and anti-diet perspective. This means I will never use food moralism to tell you to replace foods you love with foods you hate. I will never use intentional weight loss as a therapeutic goal. I will never collude with fatphobia in our therapeutic work.” In layman’s terms, this apparently seems to boil down to accepting—or even celebrating—obesity as part of a normal healthy lifestyle.

Watching Rashatwar’s heavy breathing and frequent labored pauses made me flinch with recognition. I still have an audio recording from the days when I was 100 pounds heavier than I am today. I huffed the same way. I can envision what that breathing pattern would become if Rashatwar—or the old version of me—were forced to climb a set of stairs. The pain in the chest, the attempt to mask how desperately air was needed between closed lips, delaying the frantic heaving until no one was around—I remember it all. Yet Rashatwar dismisses such concerns as artifacts of “white-settler colonialism,” and, in her speech, claimed that “my fat doesn’t make my life hard to live. It’s fatphobia that makes my life hard to live.” Unfortunately, gravity wasn’t invented by white settlers. Nor do the rules that govern the human cardiopulmonary system operate according to skin colour.

Rashatwar claims she is a “survivor” of fatphobia. I am a survivor of fat. I share her use of the word “survivor” because when I was standing at 4’10” and 300 pounds, my obesity almost took my life. A kinesthesiologist friend told me that the physical toll on my body was the equivalent of more than 400 pounds of weight on an average woman. I had sleep apnea to the point where I woke up with headaches every morning due to lack of oxygen. I had developed the characteristic black ring of dying, diabetic flesh around my neck. My menstrual cycle had abated completely, and the smallest amount of activity—going to the laundry room in my apartment complex—had become so difficult that I was forcing family members to do mundane tasks on my behalf.

I don’t use the word “phobia” to describe how other people regarded me. But, yes, I do remember feeling a crippling sense of social shame. I remember being unable to shop in any normal store for clothes. I remember sitting in my university lecture hall, unable to close the flip-desk over my lap because I was simply too big. I also remember the indescribable sadness that came with all these things, which sometimes compelled me to seek out figures such as Rashatwar, who offered some hope of lessening my sadness. For she is not alone: There’s a whole movement out there called Health at Every Size (HAES)—sometimes classified as a doctrinal sub-branch of the “fat acceptance movement.” I had a very brief flirt with HAES after becoming angry at just how excluded I was, how worthless I felt as a human being in the eyes of others.

I don’t agree with most of what Rashatwar says, and I do believe her faddish, social-justice approach to health is nonsensical. But as someone who has survived morbid obesity, and who solidly believes in the benefits of healthy living, I also oppose the way anti-HAES advocates (or, in many cases, trolls) attack or mock those who embrace HAES ideas. In online forums, one can observe a cycle by which strident anti-HAES critics cause defensive-minded HAES advocates to cling to their “fat acceptance” notions all the more insistently.

On this, Rashatwar and I agree: People have an inherent value, no matter their weight, and no one should ever be mocked, abused, or excluded on the basis of how they look. An acknowledgement must also be made to the effect that losing weight is tremendously difficult for many people, as studies have demonstrated that the foods that contribute most to weight gain behave like drugs in our system. You can be addicted to certain kinds of foods in a very real sense. Many morbidly obese people, myself still included, have food addictions or binge-eating disorders. These are real psycho-medical concerns that are still poorly understood with few effective medical interventions.

But there are also other equally indisputable truths regarding human health that Rashatwar and many HEAS advocates dangerously deny. And one of them is that being obese will make you die earlier, regardless of how enlightened everyone around you might be, or how effectively we wage war against “fatphobia.”

I can attest that Rashatwar is correct when she says that medical practitioners often gloss over an overweight patient’s medical concerns, and instead lecture them simplistically to “lose weight.” Rashatwar mentions the case of Ellen Maud Bennette, a 64-year-old Canadian woman who died of cancer. Her obituary noted that doctors had stood by for years without delivering proper oncological care, because they were more concerned with hectoring her about her weight. By the time Bennette was diagnosed, she was terminal. But it is misleading to focus on anecdotes without also noting that 18% of all deaths in the United States are obesity-related—something Rashatwar seems to ignore. If a doctor does all the necessary tests on a patient, and the recommendation still boils down to “lose weight”—as it sometimes does—is this still “fatphobia”?

Like other members of the HAES movement, Rashatwar effectively argues that since problems such as coronary artery disease and diabetes can be addressed through medical interventions, it’s discriminatory to tell patients that they should instead change their body size through diet and exercise. But even a layperson knows that this core claim is ridiculous, because the two approaches aren’t mutually exclusive: Healthy living that promotes strong baseline health levels is entirely consistent with drugs, surgeries and medical therapies that cure or palliate the ailments we all inevitably contract. And so it amazes me that medical students can sit through Rashatwar’s lectures with a straight face.

After decrying the differentiation between different kinds of food, and peddling the fiction that all foods present equal nutritional benefit to the body, Rashatwar stated in her St. Olaf speech that the Christian-supremacist concept of “purity” had contaminated our conception of food and health, and noted that “we see parallel conversations in the denial of sex as pleasure and food as pleasure.” This is nonsense on the level of her Nazi metaphors—and seemed especially absurd when juxtaposed against Rashatwar’s respectful posture toward Indigenous peoples—for it is universally understood that the introduction of heavy refined starches and sugars to the Indigenous people of North America was a chief contributor to high obesity rates and other poor health outcomes. Was it “fatphobia” when, in 2015, the Navajo/Diné nation imposed a tax on junk food and sugary drinks to curb the popularity of refined, fatty foods in their territories? Are Indigenous activists who advocate for healthy forms of traditional eating fatphobic? What about those who share Rashatwar’s South Asian ancestry? Many are raising concerns about the introduction of Western-style foods, and one would assume this is a more authentic approach to local health needs than Rashatwar’s apparent insistence that KFC and Domino’s Pizza are on the same nutritional plane as fresh vegetables and lean meats.

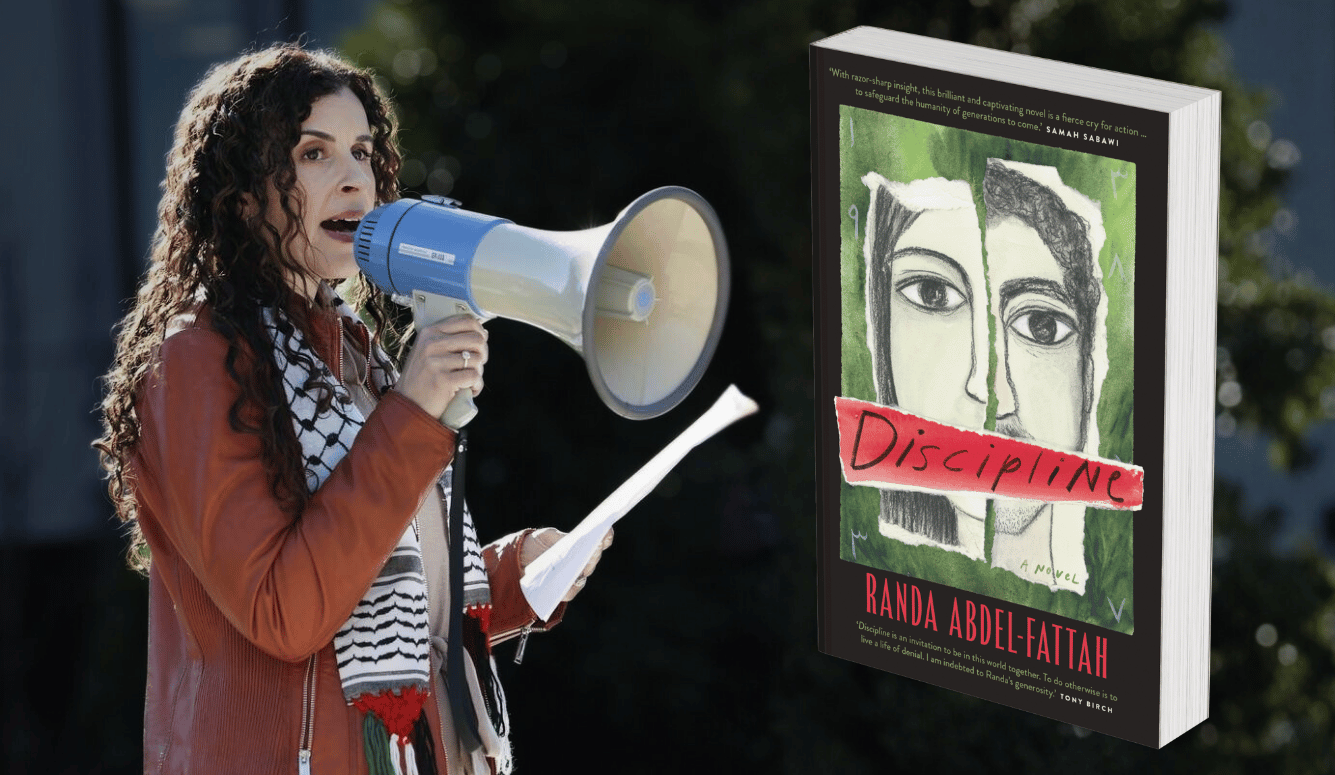

Rosie Marcado

Rashatwar’s repeated use of the word pleasure to describe our relationship with food struck a chord with me. Food is a source of joy, certainly, especially when it is shared with others. But her apparent suggestion that it exists on the level of sex, and even love, seems a recipe for sadness and loneliness. When I was heavier, food was a coping mechanism, a codependent false friend, like a pack of cigarettes. It didn’t judge, and always gave me a rush. Rashatwar’s insistence that it’s “fatphobia”—as opposed to actually being fat—that keeps her from leading a full life sounds like the internal negotiating script of an addict. The task of losing weight forces an obese person to deny themselves the passing pleasures associated with certain food. Rashatwar’s workaround is to externalize the problem—by insisting that society implement infinite accommodations for an infinitely growing body. On a psychological level, Rashatwar’s approach also allows her to channel negative feelings into defiance, and even anger—which are easier feelings to manage than shame, guilt or sadness. Her ideology provides a shield from bad feelings, at the expense of the body’s health needs.

I cannot presume to know what will become of Sonalee Rashatwar, long may she live. If she ever does decide to lose weight, I hope she is successful in that journey. But Rashatwar should be forewarned that, as with ex-HAES plus-sized model Rosie Marcado, who received death threats after losing 240pounds, the pleasure-seeking monster she helped create will never forgive her. For it is not just food that can seize us in the claws of addiction, but also the seductive ideologies that offer license to consume it with self-destructive abandon.

Anna Slatz is a Canadian writer. Follow her on Twitter at @YesThatAnna.

Featured image: Portrait of Daniel Lambert (1770-1809). Date circa 1800. Oil on canvas. Unidentified painter.