recent

The Fall of a Third-Rate Stalin

Dissidents who weren’t assassinated outright might end up in Mile 2 Prison. Only a handful of Mile 2 inmates actually faced lethal injection—the prison’s principal methods of execution were disease and malnutrition.

His Excellency the President, Sheikh Prof. Alhaji Dr. Yahya A.J.J. Jammeh Babili Mansa, ruled the Gambia for 22 years. During those decades, he did everything to transform himself from an undistinguished army officer into a bona fide eccentric dictator, complete with an elaborate personal mythology and a list of honorifics longer than the presidential convoy.

At no point did the US consider convening a coalition to invade the Gambia and depose Jammeh, despite plentiful evidence that he kept power through election-rigging and police thuggery. Why not? Because the Gambia is irrelevant to almost anyone who is not inside it. A country the size of Connecticut, whose main export is peanuts and whose main import is IMF loans, the Gambia is so puny that it evokes the contempt even of other West African nations. When Jammeh announced that he would behead any gay man caught in the Gambia, it elicited a flurry of Amnesty International press releases and not much else.

Those outraged press releases were, of course, just what Jammeh was after—proof that he and his party, the Alliance for Patriotic Reorientation and Construction, were ruffling the feathers of Western colonialists. By the end of his career, Jammeh had become fairly expert at grabbing headlines at minimal expense. After all, it costs nothing to announce to the world that you’ve been appointed Admiral of Nebraska or that you’ve discovered the cure for AIDS, but the return in column-inches can be generous. When Jammeh declared the Gambia an “Islamic state,” changing nothing, the BBC and the Independent pontificated about the implications. When Jammeh made female genital mutilation illegal, the Guardian and Al Jazeera took notice, despite the fact that almost nothing was done to actually enforce the ban.

In 2015, when I arrived in the Gambia as a Peace Corps Volunteer, Jammeh cut a memorable figure: shaven-headed, sporting aviator sunglasses, and often carrying a Qur’an and a wooden baton said to possess supernatural powers. Jammeh had traded in his fatigues for a voluminous white robe symbolizing his holiness and, at least theoretically, obscuring the fact that he had doubled in mass since assuming office. In practice, this resplendent white get-up was evocative not so much of Muhammed as of Hermann Göring.

By this time, nearly every channel of media and culture had been bent to glorifying Jammeh and the July 22 Revolution that had carried him to power. (Wikipedia tactlessly refers to this illustrious event as a coup d’état.) Stalin had Gorky, Eisenstein and Pravda. Jammeh had a motley assemblage of rappers and reggae singers, as well as the Observer, the Gambia’s only color newspaper.

The Observer practiced a kind of cargo-cult journalism, organizing text and images into columns just like a real paper, but to little clear purpose. The political cartoons were a particular delight: confined to slavishly exalting the status quo, the Observer’s cartoonist was challenged with continuously reformulating the message that everything was good and inexorably getting even better. (A typical cartoon depicts a pipe labeled “July 22 Revolution” spilling water labeled “freedom” onto the roots of a tree labeled “the Gambia.”) I possess a copy of the Observer that is 32 pages long and yet contains 17 images of Jammeh, along with the wonderful headline, “President Jammeh’s Bags of Surprises for Women.”

The text of the Observer was a mishmash of original reporting and articles cut-and-pasted from the BBC and the New York Times. The quality of the Observer’s journalism can be seen in this passage from an article titled “Diaspora Gambians Urged To Be Mindful of Insidious Oppositions”:

I am no more than a patriot who believes with all his heart and soul in the rightness of our cause, the justness of President Jammeh’s rule and in the moral purity of or [sic] people, the people of our beloved Gambia, but then this is nothing unique; as I know you all feel the same way too. Let us move forward together under President Jammeh’s rule. Forward, towards a peaceful, prosperous and harmonious future. These criminal [sic] will not beat us, they will not cower our people with false promise, outright lies and coercion. The rule of law, the justness of our cause and the true hearts of our nation will ensure that God bless [sic] President Jammeh and the people of Gambia.

Of course, in a nation with 50 percent literacy, the power of the press was limited. Outside the urban center of Kombo, most Gambians kept tuned in to events by television, radio, and phone. TV news was confined mostly to simpering announcements of the latest accomplishments made and plaudits won by Jammeh, who was usually referred to by his full title: “His Excellency the President, Sheikh Prof. Alhaji,” et cetera.

Though the APRC’s official line was one of pan-African and pan-Islamic unity against Western interference, Jammeh encouraged mild expressions of tribalism—not enough to start a civil war, but sufficient to keep the Mandinkas, Fulas, and other major tribes from uniting against him. Jammeh was a son of the Jolas, a tribe comprising only 10 percent of the Gambia’s population and known more for its musical traditions than for its martial ones. Jammeh gave the Jolas an enormous visibility boost over the more established tribes, but the truth is that Jola villages went without electricity, running water, and school supplies as much as most others. They would always vote for Jammeh, a fellow Jola, over any challenger, so why waste money buying their allegiance? When Kapa, the Jola village to which I was posted, received a water pump, it was from a German NGO, not from their supposed benefactor.

* * *

Jammeh was born not far from Kapa, in the village of Kanilai. After Jammeh’s ascent, Kanilai had been transformed from a normal huts-and-fields village into a kind of dilapidated labyrinth of painted concrete walls, an architectural achievement his supporters seemed to consider on par with the Florence Cathedral. Every so often, the people of the countryside would be called on to plow, plant, and harvest at Jammeh’s Kanilai farms. Jolas considered this unpaid work a true privilege—just being of service to the big man was reward enough. Members of other tribes often showed as little enthusiasm as they could get away with, but the Jolas were true believers.

Other not-officially-mandatory duties included standing at the roadside when Jammeh was expected to pass. When the presidential motorcade roared along the otherwise quiet Trans-Gambia Highway, it was difficult to miss, and His Excellency would occasionally pop out of the sunroof and wave excitedly at us, his white robe billowing enormously.

While many hoped to evade the big man’s notice, others fought to grab his attention. On motorcade days, Jammeh supporters would leave material offerings on the shoulder of the highway, a practice that took on religious overtones. If one left a sufficiently tempting offering—several liters of honey, or a man-sized stack of maize—Jammeh might stop to receive your gift, giving you an opportunity to beg his blessing. He never did stop, of course—what would a man with 13 Bentleys want with a plastic jug of honey? Unlike Cain, however, Jammeh’s devotees always blamed themselves.

Outside of the Gambia, Jammeh’s childishness made him a clown rather than a tyrant. Few journalists could resist leading stories about Jammeh’s miraculous AIDS cure, and reports of widespread torture, censorship, and paranoia often disappeared behind his elephantine white bulk. Stories of midnight abductions were never too difficult to come by, at least outside of Jola communities. Dissidents who weren’t assassinated outright might end up in Mile 2 Prison. Only a handful of Mile 2 inmates actually faced lethal injection—the prison’s principal methods of execution were disease and malnutrition. Amadou Scattred Janneh, an activist sentenced to life imprisonment for distributing anti-APRC t-shirts, described being kept in a crowded cell for up to 20 hours per day, deprived of food and medical care. During Janneh’s incarceration, the prison’s Security Wing, with a population of about 150 inmates, averaged one death per month.

But even some Peace Corps Volunteers treated the Jammeh regime as merely ridiculous: one volunteer remarked to me that the Gambia would never be a real police state because Gambians were simply too unintelligent to run one. (Later, in a more public setting, I listened to the same person explain the need for volunteers to “unpack their privilege.”)

All totalitarian imagery eventually devolves into kitsch. It seems clear, however, that the great totalitarian societies achieved, in their moment, a kind of perverse splendor. There’s little doubt, for instance, that the 1934 Nuremberg Rally must have been quite something to see. Even Senegal’s horrendous, North-Korean-built “African Renaissance Monument” succeeds in cribbing a little bit of Stalinist majesty. The Jammeh regime, on the other hand, was pure kitsch from the start—ramshackle triumphal arches, lumpy statues, and bombastic proclamations riddled with malapropisms.

In the countryside, Jammeh’s presence was usually emblematized by tattered green banners. In Kombo, however, seemingly every flat surface bore his photograph: he appeared in stickers on the windows of taxicabs, in framed portraits hanging in hotel lobbies, and in billboard advertisements. On Kairaba Ave., Kombo’s main drag, was a mural of Jammeh surrounded by cowrie shells, painted with the idiotic glow typical of personality-cult portraiture. One small problem—some anarchist had bashed in Jammeh’s face. For me, this mural perfectly described Jammeh’s Gambia. No doubt the vandals would have vanished forever if the local secret police had been prepared to catch them, but I doubt they did. The Gambia was run with the brutal grandiosity of a Stalinist state, but without the consistency. It was totalitarianism mediated by disorganization.

* * *

In the Gambia, political tribalism and witch hunts could be seen in their original forms. Jammeh, who believed his aunt had been killed by sorcery, considered witches a greater threat to public health than malaria. This seems to have been genuine conviction on Jammeh’s part, and not a calculated attempt to clothe political repression in folk beliefs. The deadly witch hunts carried out by Jammeh’s presidential guard in the 2000s did not target only dissidents, but entire villages from the region around Kanilai.

The witch hunts seem eventually to have wound down. When, in 2016, Kapa was rifled through by a squad of GAF soldiers accompanied by a shirtless mystic, the mood of the village was more curious than frightened. After a house-to-house search, the soldiers located the tree a local witch had been using as a repository of magic energy, shot it with their rifles and then departed. The teachers, many of whom had been educated in Kombo, stood together at the back of the crowd, trading skeptical remarks.

Jammeh was not Mobutu—he believed in his own mysterious powers almost as naively as did his followers. Despite attempts by both comrades and enemies to paint him as a sophisticated operator who studied Marx and Mein Kampf, the primitive and superstitious quality of Jammeh’s worldview can be seen everywhere in his presidency, from his witch hunts to his anti-AIDS elixir to his magic baton. Even during his army days, Jammeh rubbed himself with leaves for protection against evil spirits, says Essa Bokarr Sey, former Gambian ambassador to the US.

Jammeh’s childish self-belief surely contributed to the election loss that finally undid his grip on the Gambia. Until 2018, Gambians voted not with ballots and boxes, but with balls and barrels. The typical villager, even if in some sense literate, lived innocent of bureaucracy, and found the finicky exactitudes of paperwork deeply unintuitive. A Gambian, then, registered his vote by dropping a glass marble into a sealed metal drum. The drums were color-coded: green for Jammeh, “ash-color” for the main challenger, Adama Barrow, and purple for the marginally popular Fula candidate, Mama Kandeh.

To call Barrow a dark horse would be a colossal understatement—Barrow was nominated by the United Democratic Party just months before the election, after the previous party leader was thrown in jail. Barrow didn’t even know he was up for the position until he saw his own name on the ballot, according to one UDP member. The Gambia’s arcane tribal disputes seemed alien to Barrow, who had spent his formative years working and studying in the UK.

In the Jola villages, people were anxious—not that Jammeh would lose the election, but that the opposition would engage in some sort of trickery or sabotage. (One rumor, proliferated by text messages, claimed that a white van full of UDP members was driving around, abducting children for sacrifice in a black-magic ritual. This was taken at least seriously enough to have school in Kapa cancelled for a few days.) The democratic process, grafted onto the Iron-Age chiefdom system practiced in the villages, was viewed almost exclusively in tribal terms: Jammeh was the Jola candidate, Kandeh the Fula candidate, Barrow the Mandinka candidate and that was that.

On 1 December, as the votes were being tallied, I joined other volunteers around the radio. One division after another went to Barrow—even in the Jola-heavy West Coast Division, Jammeh prevailed by only a single percentage point. Around 3:00 am, announcements ceased.

The next day, the Independent Electoral Commission declared Barrow the winner by 8.8 percentage points, and Jammeh appeared on TV to announce that he would step down without fuss and support Barrow through the transition. This historic moment was slightly marred by poor cell reception during Jammeh’s congratulatory phone call to the president-elect. In just a few hours, the Gambia had turned upside down: His Excellency the President, Sheikh Prof. Alhaji Dr. Yahya A.J.J. Jammeh Babili Mansa, witchfinder general, curer of AIDS, and Admiral of Nebraska, was now merely a citizen. Jammeh had at one point declared that he would rule for a billion years, so, to hear him willingly give up the presidency 999,999,978 years ahead of schedule was, to put it mildly, a surprise.

In the minutes following Jammeh’s concession, the streets of Kombo flooded with crowds sporting UDP yellow and coalition “ash-color.” Over the afternoon, Jammeh vanished from the city as all his innumerable images were ripped down, painted over or broken in two. It was the fastest I’d ever seen anything accomplished in the Gambia.

Celebration of Jammeh’s downfall was performed as unanimously as support for him had been until a few days ago. Taxis roared down Kairaba Ave. with passengers hanging out the doors or splayed over the windshields. People took turns snapping selfies as they trampled on toppled images of His Excellency. Many simply seemed intoxicated to break such a taboo.

When one of my Jola students saw my photos of this merriment, she remarked sourly, “The Mandinkas are celebrating.”

* * *

It’s said that, during the Tobaski festival, everyone in Kombo is Muslim, and, on Christmas Day, everyone in Kombo is Christian. On the day Jammeh conceded, everyone in Kombo became a dissident. Imagine, then, the dismay when Jammeh appeared on TV a week later, looking haggard and possibly tipsy, and announced that he was no longer willing to concede. He would stay in office until serious but unspecified irregularities in the election results could be resolved. This was Jammeh’s biggest-ever publicity stunt, one that put him at the top of the New York Times homepage.

During those seven days, many Gambians had done what they had never dared before: to broadcast anti-Jammeh messages on social media. If Jammeh stayed in power, would they find themselves locked up at Mile 2 with the other dissidents?

Needless to say, Jammeh was the only one able to discern just what was illegitimate about the first election. Everyone from the United Nations to the Gambia Teachers Union agreed that conceding an election and then attempting a self-coup was not to be done—not even in the Gambia. Leaders of the Economic Community of West African States, flew in to meet with Jammeh. The images that emerged looked less like negotiations among statesmen than a therapeutic intervention.

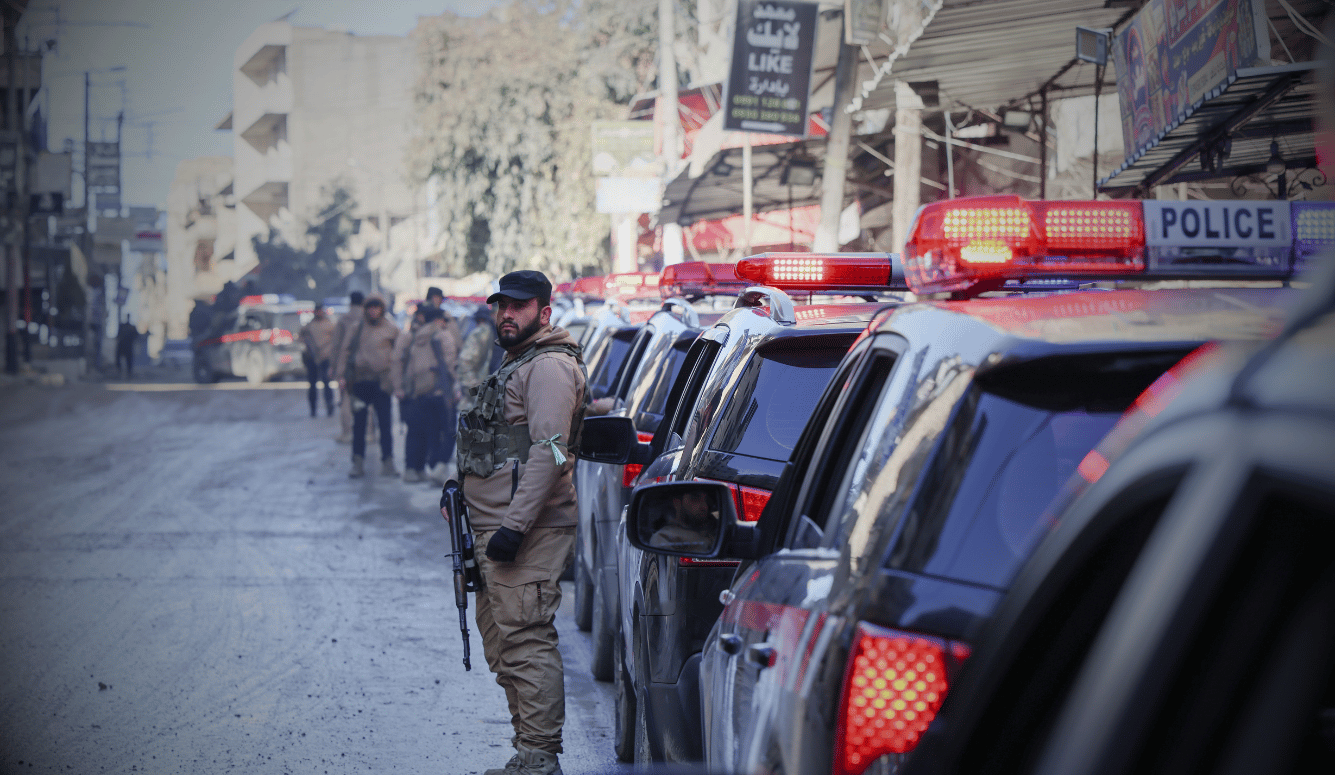

There was no question of the Gambia’s 2,500-man army resisting a joint invasion by the 15 ECOWAS member states. After 22 years of shooting protestors and abducting dissidents, the GAF wasn’t prepared to tangle with an armed enemy. (Anyone who believes I’m being uncharitable can refer to the 1996 incident in which six men managed to take over a Gambian army base.) On 19 January 2017, ECOWAS executed the imprecisely named “Operation Restore Democracy”: a mainly Senegalese force of 8,000 rolled across the border while the GAF, for the most part, stood aside and watched. On 22 January, Jammeh finally capitulated and boarded a plane for Equatorial Guinea. It later transpired that he’d spent his last few days in office rescuing his Bentleys and ransacking the treasury and the national social security fund.

Like all other Peace Corps Volunteers, I was absent for Operation Restore Democracy. The rest of my cohort was evacuated to Dakar, whereas I had, quite fortunately, scheduled a Christmas vacation to Australia. As a result, while most other volunteers were inexorably descending into a kind of inebriated, nymphomaniacal cabin fever in a Senegalese hotel, I was strolling through the picturesque rainforests of Far North Queensland. When we finally returned to the Gambia, the grinning portraits of Jammeh had been replaced by photos of an uneasy-looking Adama Barrow.

Barrow was everything Jammeh was not—he did not make rabble-rousing speeches, he did not want to decapitate homosexuals, he did not ride up and down the Trans-Gambia Highway waving at people, and he did not carry a magic stick. He was, in a word, normal, at least from my perspective. Barrow’s low-key approach won him few admirers in the villages, however. A photo emerged of Barrow reclining on a sofa, which earned him the nickname “sleeping president” among Jammeh loyalists. It seemed lost on them how remarkable it was that they were able to laugh at the “sleeping president” without fear of being strung up by their toes.

When I returned to the Gambia in February 2017, I found Kapa defiant: a photo of Jammeh was nailed into the mud-brick of my compound, and threadbare green cloth hung everywhere. As convoys of Senegalese Jeeps rolled down the highway toward Kanilai, an acquaintance of mine remarked bitterly: “When Jammeh comes back, all these people will be in prison.” When I asked how Jammeh could return if the GAF refused to fight for him, my acquaintance explained that they hadn’t: “The army wanted to fight, but Jammeh told them not to. Jammeh doesn’t like fighting.”

Jammeh’s sabotage of the educational system had served him well—his soldiers had stood down, but these villagers would never forget their loyalty to him. In 2018, leaked audio indicated that Jammeh too expected he would return from his equatorial Elba: “When it is time for me to come back to the Gambia, no one can do anything about it. No human or jinn can stop it from happening.”

Jammeh’s supporters will probably spend the rest of their lives venerating his portrait and waiting for his second coming. No doubt their rugged and unglamorous lives are far from Jammeh’s mind as he settles into a lavishly funded exile, where he will be shielded from extradition.

Only Kapa’s children seemed able to let go of Jammeh’s grand vision—they feared war more than they desired Jammeh’s return. A few months after Barrow took office, a Jola girl explained to me that she would peacefully support whoever was president, whether it happened to be Yahya Jammeh or Adama Barrow. Only the young could truly cut ties.

“His Excellency Adama Barrow,” she said, trying out the sound of it. “Sheikh Prof. Alhaji Dr. Adama A.J.J. Barrow…”