Cinema

Dragged Across Concrete—A Review

In a cultural moment that has seen reputations destroyed by a single tweet, each transgression can become the entirety of a person’s character.

It may very well be that the individual who has been expelled, and who has now become embittered and reckless, will cause us further trouble.

~Freud

The kind of trouble to which Freud alluded rears its head in S. Craig Zahler’s brutal new feature film Dragged Across Concrete, an exploration of two characters emblematic of that proletarian section of American society notoriously dismissed by Hilary Clinton as a “basket of deplorables.” Brett Ridgeman (Mel Gibson) and Anthony Lurasetti (Vince Vaughn) are haggard, vulgar, politically incorrect white male detectives who “don’t politick or move with the times.” Consequently, they are not the sort of people whose “truth” our febrile zeitgeist is especially keen on hearing.

Ridgeman and Lurasetti are working pariahs on a measly wage; they have paid their dues and followed the rules, and have little to show for it besides bitter disenchantment with the social contract. “One year away from 60,” Ridgeman complains, “and I am still the same rank as when I was 27.” Trapped by his income in a decrepit community, he is unable to afford the medical costs needed to treat his ailing wife (Laurie Holden) or secure his daughter’s future. The plot of Zahler’s movie turns on the scandal that erupts when the cops’ violent interrogation of a Latino suspect is caught on camera, and the two men find themselves ensnared in a PR nightmare and faced with the economically devastating prospect of six weeks suspension without pay. “We need the hours,” Ridgeman protests desperately. Sympathetic but unable to help, Chief Lt. Calvert (Don Johnson) grumbles, “Like cell phones, and just as annoying, politics is everywhere.”

As might be expected in today’s climate, the film is facing accusations of reactionary messaging and racism. The production company behind the film, Cinestate, previously produced a series of low-budget violent pictures including Bone Tomahawk (2015), Brawl in Cell Block 99 (2017), and The Standoff at Sparrow Creek (2018), and has been described as the purveyor of films that “reflect the Trump-era mix of fear of the outsider and paranoia about the government.” While these films do reflect the Trump era to a degree, the implication that they are exploiting “populist” anxieties for either ideological reasons (S. Craig Zahler has been called a “white supremacist”) or a quick buck, is hardly fair. In fact, this latest Zahler/Cinestate collaboration is doing something of which American politics (and filmmaking) are currently incapable: lending the deplorable demographic an empathetic ear. “Being called a racist,” a character complains in one deliberately provocative line, “is like being called a Communist in the ‘50s.”

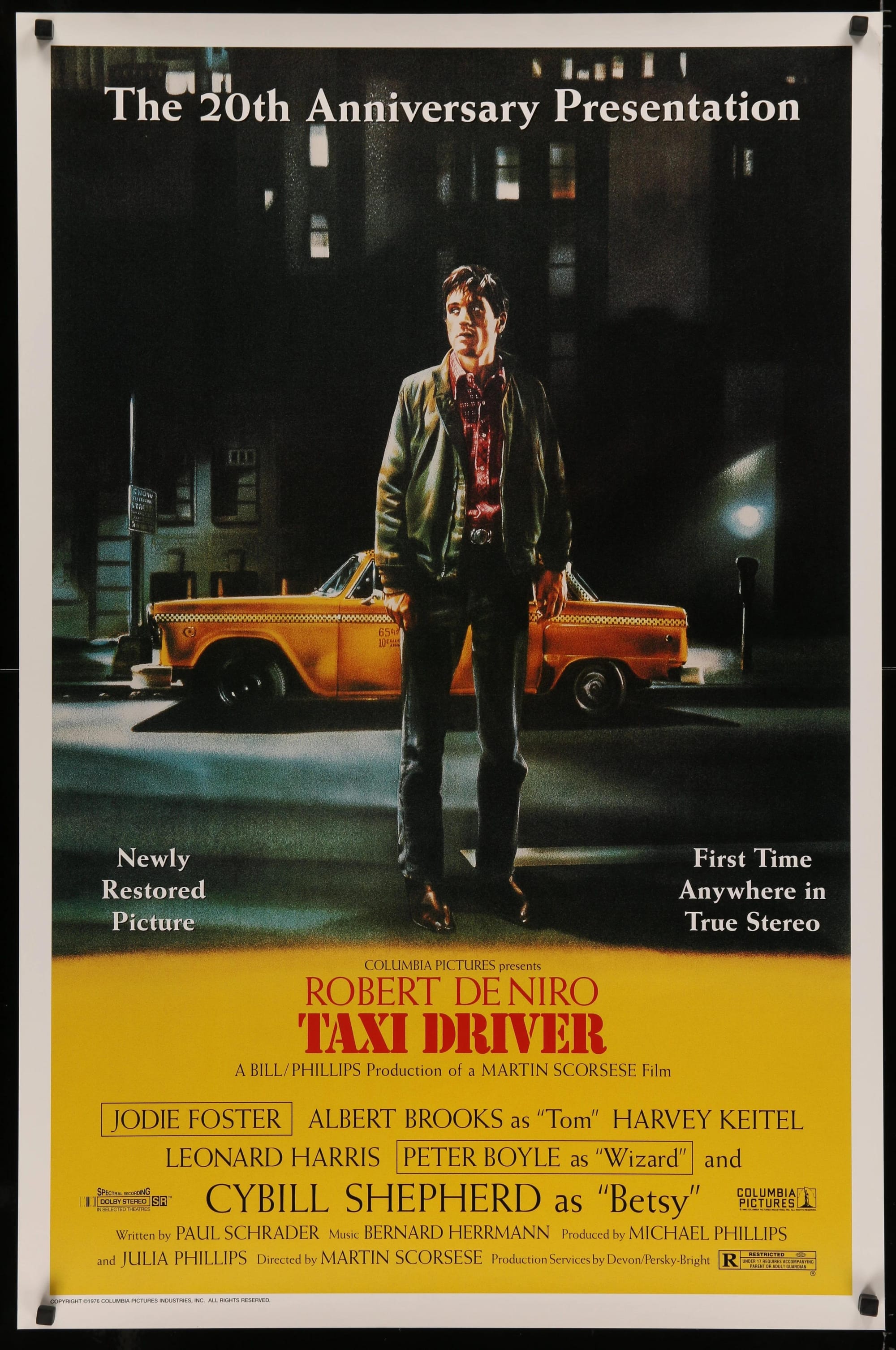

In its attitude to the misfit and social outcast, the film recalls Taxi Driver’s lonely and damaged protagonist Travis Bickle (Robert DeNiro)—like Bickle, Ridgeman and Lurasetti inhabit a milieu of urban despair, alienation, silent resentment, and social dysfunction. Naturally, in a culture that routinely confuses empathy with sympathy, adopting such an approach was bound to provoke controversy. When Taxi Driver was first released, a number of progressive critics were either reluctant or unable to distinguish between the attitudes of the protagonist and those of the filmmakers, which left director Martin Scorsese and screenwriter Paul Schrader facing accusations that they had made a pro-vigilante and even fascist movie. The Daily Beast’s overwrought description of Dragged Across Concrete as a “racist right-wing fantasy” indicates that critics remain less keen on evaluating the metaphorical or aesthetic truth of art and entertainment than policing it.

Today, artists have been put on notice that aesthetics are less important than politics, and that those politics are expected to be explicitly progressive. Moral responsibility is heaped onto objets d’art whether the artists like it or not and the only important distinction is between pure and impure art. Paternalistic assumptions about what the masses are capable of seeing—as if merely portraying something unsavory constitutes endorsement—is condescending, censorious, and anti-art. At the last Berlin film festival, a number of critics were so outraged by Fatih Akin’s new serial killer picture The Golden Glove, they told me that merely reviewing it—negatively or otherwise—should be understood as an endorsement of its allegedly regressive politics.

But such crude utilitarianism is a misunderstanding of art and what it is for. Art is not political, it is spiritual—a “tabooed logic” in the words of Herbert Marcuse. It allows us to experience urges and irrationality we must otherwise suppress and to empathize with others as a means of understanding ourselves. Art does not exist solely to create a better world, it exists to reflect the one in which we live in all its beauty, ugliness, and maddening complexity—and, in this respect, Dragged Across Concrete excels, stranding its audience within an optimal zone of discomfort using an enthralling balance of moral ambiguity, questionable ethics, dark humor, and sadistic violence. Zahler is artfully out-of-sync with progressive imprimaturs, a filmmaker willing to complicate easy identification and moralism and to locate pathos in taboo.

Following their suspension, Ridgeman and Lurasetti respond in the only way they know how—they formulate a desperate plan to intercept a robbery and make off with the riches. Needless to say, as a result of happenstance, stupidity, and spiraling unintended consequences, things do not go according to plan. Sympathetic cultural critics have interpreted the narrative as a cautionary tale about the wages of moral turpitude and, from this reading, a surreptitiously progressive “message” can be salvaged. But this is an equally reductive and exclusively political paradigm, whether it is deployed by the Right or Left. The difficult truth about Dragged Across Concrete is that it’s neither progressive nor reactionary; liberal nor conservative. Rather, it exists as a thorn in all of our sides, refusing to offer even the reassuring catharsis of a redemption parable. With a brutal, if almost Zen-like detachment, Zahler tells a story about the brutal logic of action and consequence. If there is a moral, it concerns the vital importance of discernment. For while the film confines its profoundly flawed protagonists within an unforgiving socio-economic context, these men are not a social symptom but moral agents culpable for their own choices.

And yet, even a film as resolutely apolitical as this one resonates with contemporary political discontents. Zahler has his finger on the cultural pulse, even if it’s not entirely clear if he believes there’s a heartbeat worth saving. As the violent narrative closes in on its inevitable denouement, Lurasetti says, “I hope I am not remembered for this mistake.” But we know he is lost because the culture has commanded it. In a cultural moment that has seen reputations destroyed by a single tweet, each transgression can become the entirety of a person’s character. Beneath the car chases, shoot-outs, and smart dialogue in Dragged Across Concrete is an elegy, not for the passing of time (this isn’t a nostalgic film), but for those left behind when the cultural baton is passed from one generation to the next. The hands that built the nation are now tainted, their flaws have been exposed and denounced, and swathes of our fellow citizens have been condemned as unclean rabble-rousers. Here is a film that speaks to this cultural tragedy in the shape of two flawed cops, resigned to a world that despises them but doing their awkward and imperfect best to stay afloat and do the right thing as they understand it.

In Depth Psychology and a New Ethic, psychologist Erich Neumann cites “detective stories, crime films, and thrillers” as “evidence of the decline of the old order of life in the realm of aesthetics.” But this was no conservative lament. Rather, he saw in a film like Dragged Across Concrete “the germs of any possible future development in the West,” precisely because it is so defiantly amoral. The student of Jung suggests that an ethic forged in binary notions of “good” and “evil” inevitably leads to projections of our dark side onto the Other. This is how the individual is disappeared, how scapegoats are created, and how totalitarian thought takes root. To avoid this, wrote Neumann, we have to recognize our own capacity for evil.

Our polarized political discourse has been consumed by the old binary ethic. So, if politics won’t do the job of mediating between the lowly and dignified, art must. Far from being fascist, Dragged Across Concrete is a braver and more perspicacious piece of work than many of those films applauded for the correctness of their politics, irrespective of the paucity of their insight; it negotiates a relationship with the nastier aspect of ourselves in an attempt to save our culture, and to salvage the deplorables from the basket of history in the name of our universal humanity.