Long Read

The Death of a Dreamer

When a public figure makes a mistake there seems to be a much stronger, more intense and quicker backlash.

The following is a lightly adapted extract from Will Storr’s latest book Selfie: How We Became So Self-Obsessed and What It’s Doing to Us, Picador (June 15, 2017), 416 pages.

Imagine that it were possible to create the perfect human. The process would be like making an app, but instead of computer code, your design language would be DNA. You’d do the creating itself on your smartphone—using a piece of software called a Genome Compiler—then email what you’d come up with to a laboratory. Technicians in that lab would manufacture the DNA, per your instructions, dry it out, then send it back to you. After all, DNA isn’t alive. It’s a polymer, an arrangement of four different chemicals. Theoretically, from that DNA, it would be possible to construct the most advanced forms of life. You could make your human a super-genius, immune to all kinds of diseases. You could even make them live forever. After all, we only age and die because the DNA program we’re running—our human code—contains an instruction to do so. Just get rid of it. Rewrite it. Why not?

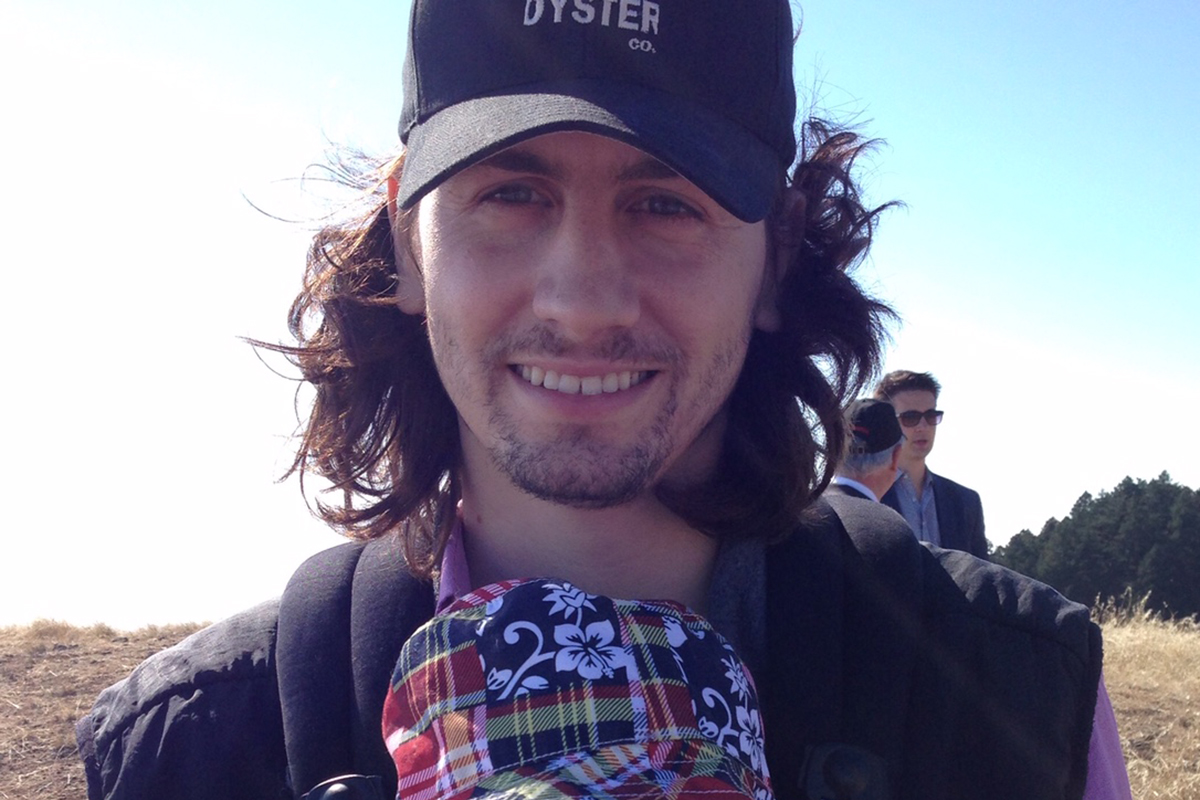

This was the dream of a visionary young entrepreneur named Austen Heinz. At school, back in North Carolina, Heinz had been bullied, sometimes badly—the combination of his physical slightness and social illiteracy had seen to that. He was bad at reading people. He had a kind of genius for absorbing large amounts of complex information at great speed, but when he arrived at an opinion, often after a period of intense labour, he’d announce it provocatively and unapologetically. He’d found it difficult to find friends and he’d struggled with his mental health. But now, at the age of 30, he was living a few blocks from his own laboratory, in a high-rise apartment in San Francisco’s tech district, looking out over 180-degree views of the Bay Bridge, the AT&T ballpark and the stunning harbour, everything seemed to be coming together. Among the Silicon Valley cognoscenti, Heinz was seen as a major rising talent. His idea and his company, Cambrian Genomics, was about to change everything. Of that he felt sure. As he’d tell investors and journalists again and again, the tools they were developing would one day be more powerful than the hydrogen bomb.

He didn’t even think we should stop at redesigning humans. We could design and create any form of life. In the future, he believed, we wouldn’t leave it to messy nature just to plop everything out, riven, as it always is, with all those hundreds of thousands of little genetic imperfections that add up to sadness, illness, and death. Everything would be synthetic, designed for purpose, including our children, including us. The only things that would limit us would be our DNA programming abilities and our imaginations. Everything alive is made up of just 20 different amino acids. Why not expand the range? Make some new ones? Incorporate metals, say, into plants or animals? Imagine the possibilities. Imagine the problems we could solve. And, eventually, we wouldn’t even need to use Cambrian Genomics’ expensive equipment.

Not everyone was convinced of the viability of Heinz’s ambitions. Some found his speculations about the possibilities offered by synthetic genomics hopelessly quixotic. But others continue to believe that history will one day crown Heinz one of the heirs of information age visionary Doug Engelbart—a restless, optimistic, socially-maladjusted prophet of the oncoming Synthetic Age in which the project isn’t to augment human intelligence, but humans themselves. His supporters argue that the future foretold by Cambrian Genomics will not necessarily be the dystopia critics fear. By curing all disease, living forever, and solving some of the planet’s most enduring technical problems without destroying it in the process, Heinz speculated that we could considerably reduce the sum of human suffering and unhappiness. It’s true, of course, that only the lunatic talks earnestly of paradise. But how crazy do you have to be to think that with this technology, we could move ourselves an inch, even a mile, towards it?

Not only was Austen Heinz convinced that all this was going to happen, he was sure he knew how to do it. This was at the end of 2014. In less than six months, he would be dead.

It was at Duke University, whilst working on a synthetic biology research project, that Heinz came up with a new and efficient way of producing usable DNA that reduced the cost from tens of thousands of dollars to just a few. “Everyone else that makes DNA, makes DNA incorrectly and then tries to fix it,” he said. “We don’t fix it. We just see what’s good, what’s bad and then we use the correct pieces.” This drastic reduction in cost would enable them to treat DNA like we treat data—as cheap to make and emailable, programmable. When he was in his mid-20s, at Seoul National University in South Korea, Heinz developed his concept of a “printer for DNA,” then decided that progress would be more rapid in the private sector. At 27, he returned to the United States with some bridges burned and $300 to fund his vision. He was just another West Coast brain convinced he was going to change the world.

As a kind of trial run for his technology, he and some colleagues decided to create a glowing shrub by copying some DNA code from a firefly, printing it out, and inserting it into the cells of a plant. Their test worked. Their hybrid plant glowed in the dark. They decided to put it on sale. The $10,000 they spent on a promotional video was quickly recouped: they took in almost $60,000 on their first day of sales and $484,013 within six weeks, with orders eventually building towards $1,000,000. He founded Cambrian Genomics and raised $10,000,000 from venture capitalists including PayPal billionaire Peter Thiel. His company began partnering with major international corporations, such as Roche and GlaxoSmithKline, as well as some smaller start-ups.

One of these was Sweet Peach, which had been founded by Audrey Hutchinson, a young biology student and Distinguished Scientist scholarship recipient at New York’s Bard College. After suffering a series of painful urinary tract infections, Hutchinson had become interested in vaginal health. Hearing about his work, she emailed Heinz with her idea for a company that would use Cambrian Genomics tech to manufacture vaginal probiotics. Customers would send in a swab that would be genetically sequenced. Once the specific microbial species that made up their particular bacterial community was analysed, a personalized treatment would be delivered. Heinz was immediately interested. He agreed to help, not only with the technology but also with business advice. He also took a 10 percent stake in her company.

Word of his work spread further. He met Sergey Brin from Google, Elon Musk from Tesla and SpaceX, and Jared Leto from the movies. He was invited to Richard Branson’s private island, where it is said that he silenced the billionaire’s dinner table with his vision of an intentionally designed, synthetic future. He was interviewed by Fortune and NPR and Wired. CNN named his technology as one of its “Top Ten Ideas That Could Save Lives.” He also became a frequent guest at tech conferences, and it was at one of these that a chain of events was set in motion that would lead eventually to his death.

On Wednesday 19 November 2014, Heinz spoke at a Demo conference in San Jose, California headlined “New Tech Solving Big Problems.” His fateful presentation was entitled “Create Your Own Creatures by Printing DNA.” “Our goal,” he explained, “is to take everything that’s existing and natural and replace it with a synthetic version. So, by writing the DNA we can make it better. We can make better humans, we can make better plants, we can make better animals, we can make better bacteria.” His glowing plant project might sound trivial, he acknowledged, but the implications were immense. “If you can engineer a plant to glow in the dark, imagine what else you can make a plant do. You could make a plant suck all the carbon out of the atmosphere. You could make a plant that produces food to feed the world.”

The day before the conference, Heinz had apparently been told he would be on for ten minutes rather than the three he’d been planning. To fill some of the time at the end, he decided to speak briefly about some of companies he’d partnered with who’d be using Cambrian Genomics technology. Welcoming one of these partners onstage, Gilad Gome of Petomics, he talked about the idea of changing the smell of faeces and gastric wind and using it as an alert that a person was unwell. “When your farts change from wintergreen to banana maybe that means you have an infection in your gut,” he said. He introduced Sweet Peach as a similar project. “The idea is to get rid of UTIs and yeast infections and change the smell of the vagina through probiotics,” he said.

So, not only can you actually program them, you can write them, you can change them and you can make them personal to you. You can control all the code that lives on you, which is exciting, because previously the natural world has been beyond our grasp. We’ve recently, within the last ten years, been able to read it. Now we finally have the cost low enough that anyone can write it on their phones. So the idea is, your microbes can be out of balance. Sweet Peach will balance them, improve smell, and everybody’s happy.

Everybody’s scents are bacterial in origin, he explained. They’re produced by organisms that live on you. “We think it’s a fundamental human right to not only know your code and the code of the things that live on you but also to write your own code and personalize it.” When the compere provocatively asked if Heinz and Gome were playing god, Heinz countered in exquisitely neoliberal fashion, “The idea is personal empowerment. We don’t want the state telling people what they can grow on them, what babies they have and what genes they can fiddle with. We want it to be self-directed.”

In the audience, a journalist from Inc.com decided that what he was hearing was “astonishingly sexist.” After all, here was a man, he’d later write, chattering about “making women’s sex organs more aesthetically pleasing.” It seemed to him that Heinz was just another of these “tech bros” who “talk endlessly about changing the world with technology while building frivolous things.” After the presentation, he asked some follow-up questions. In response, Gome explained that the change in scent wasn’t only there to help customers connect to themselves in a “better way,” it was an indicator that the product was actually working. “It tells us where the protein is expressed,” he said, adding jokingly, “What, would you rather have it glow?”

“These Startup Dudes Want to Make Women’s Private Parts Smell Like Ripe Fruit” ran the headline at Inc.com later that day. The story zipped around the web, being swapped and swapped and swapped again on social media, the outrage rapidly amplifying. Soon, the Huffington Post picked it up: “Two Science Startup Dudes Introduced a New Product Idea this Week: A Probiotic Supplement that Will Make Women’s Vaginas Smell Like Peaches.” Gawker called it a “waste of science” and said Sweet Peach “sounds like a C-list rom-com with a similarly retrograde view on the priorities of the contemporary human female.” Then, Inc.com weighed in again: “Its mission, apparently hatched by a couple of 11-year-old boys still in the ‘ew, girl cooties’ stage, is to make sure women’s vaginas smell ‘pleasant.’” Similarly negative stories began appearing in major news sources such as Salon, Buzzfeed, the Daily Mail and Business Insider.

These reports were profoundly unfair, and some of them were later rewritten or otherwise amended. Heinz and Gome were presented as misogynists who’d decided to concentrate their efforts on solving the problem of smelly vaginas. In truth, Heinz had spent the majority of his talk explaining the fantastic world-changing possibilities of his technology. Its title referenced not vaginas but creating “your own creatures.” He’d mentioned “vaginal smell” in a way that wasn’t entirely clear, but in the context of a discussion of health products. And even then, to excoriate anyone for working in this specific area would seem eccentric at best: over-the-counter products for vaginal odour have been available in pharmacies for years, and nobody accuses their manufacturers of hating women. Most of the news outlets now attacking Heinz and Gome were quintessential products of the internet age, relying for much of their survival on the sowing and harvesting of moral outrage.

Inc.com stoked that outrage yet further with a follow-up interview with Sweet Peach’s Audrey Hutchinson. “Sweet Peach Founder Speaks: Those Startup Dudes Were Wrong About My Company” ran the headline. “When I wrote earlier this week about a new probiotic supplement called Sweet Peach engineered to make women’s vaginas smell like fruit, the response across the internet was understandable outrage: Who the hell were the guys behind this and what right did they have to decide how women’s bodies ought to smell?” But the real story, wrote Inc.com, was “outrageous in a different way.” Inc.com accused the founders of being “highly misleading” by characterizing Sweet Peach as a tool for making vaginas smell like fruit—which, of course, they hadn’t. “It was Gome who introduced the critical misperception about Sweet Peach,” the reporter wrote, “after I specifically asked him whether the supplement was designed simply to eliminate unwanted odors, or whether it was meant to introduce desirable new ones, like the scent of peach. He insisted it was the latter, likening the new scent to a marker dye that let the user know the product was working. ‘Instead of color, this is a scent or a flavor. But it’s way cool that it smells good,’ he said.” Hutchinson told the reporter she’d been nauseated by what had happened, and even claimed to have vomited twice. “A vagina should smell like a vagina,” she told the Huffington Post, “and anyone who doesn’t think that doesn’t deserve to be near one.”

Heinz tried to rescue the situation. He apologized for leaving Hutchinson out of his presentation, explaining that he was only informed that his three-minute talk had been extended the day before and had lacked sufficient time to plan. Gome, he said, had spoken about Sweet Peach because he was excited about the science. “He’s a microbiologist and he likes to talk about possibilities.” In his typically socially-deaf way, he added that whilst the publicity was losing him investors, it would be good for Hutchinson. “This mischaracterization is going to be great for Sweet Peach.” He also desperately explained to the Huffington Post, “I never said anything about making vaginas smell like peaches.” None of this made any difference. On 24 November, Hutchinson released a series of tweets in support of Heinz. “Amidst chaos, I’m confident in saying I’m still proud to have Cambrian Genomics as a stakeholder in Sweet Peach,” she said. “Austen Heinz of Cambrian Genomics has shown me nothing but fervent support in my efforts to make Sweet Peach a force in women’s health. He’s been a friend and support throughout this entire process and has played a huge role for helping make my vision and company a reality.” But this statement, by the young female founder, was largely ignored.

Instead, the monstering continued. “How Two ‘Startup Bros’ Twisted the ‘Sweet Peach’ Mission” ran a headline on the Huffington Post: “Yup, you read that right; these ‘startup bros’ think a vagina that doesn’t smell like a peach is a Big Problem to be solved.” The Daily Mail posted another story (“Female CEO of Vaginal Probiotic Is ‘Appalled’ by Male Colleagues Who Misrepresented Her Product to the Public”), as did BuzzFeed (“the two completely mischaracterized the company . . . it does not create a peach scent for women’s vaginas”). The Guardian ran four negative stories over the course of just three days, while the Daily Dot wanted to know, “Is the Sweet Peach Startup a Complete Scam?”

“It was pretty heart-wrenching to see him suffer like that in the media,” Heinz’s sister, Adrienne, told me. We were talking in the central San Francisco consulting room where she works as a clinical psychologist, her client-base largely Silicon Valley tech workers. “It was clickbaity stuff. Article after article after article got written because the headline was interesting. It was so infuriating. I don’t think I realized how devastating it was for Austen until later.” She says he couldn’t stop talking about it.

Behind the scenes, Heinz had been trying to convince Hutchinson to include a smell signal in her product, but she’d resisted. She’d had no idea he was planning on talking about Sweet Peach, even as a relatively brief aside following his main talk. That he didn’t think to mention her name had only added to the problems. But, said Adrienne, his presentation contained no malice, and in his attempts to repair the situation, he’d only succeeded in making things worse. “He was just saying all the wrong things,” said Adrienne. “I mean, you could never describe him as socially graceful. The reporter was a really nice person but he got Austen completely wrong. He thought he was just kind of a dirtbag.”

Because of what was going on in the media, investors began backing out of Cambrian Genomics. One of Heinz’s business advisors compared his reputation in the industry to that of Bill Cosby. He’d been trying to raise a second round of funding and now he thought he’d have to start laying people off. The timing was terrible: they’d been encountering difficulties with the laser and needed all the brains they could get. “The technical problems could’ve been addressed,” said Adrienne. “He had this brilliant team of scientists that were helping and, worse-case scenario, they could’ve sold to another company who could’ve figured it out, or they could’ve persevered and eventually figured it out. That wasn’t the issue. It was more his confidence in his ability to raise money after this media fallout.”

By the end of 2014, Heinz was suffering physically. “He was like a walking corpse,” said Adrienne. “He’d stopped eating, stopped sleeping. He was just so ruminative—there was a constant stock-market ticker of how his life was over.” They’d have long conversations on the phone. “You might feel like you’d got somewhere by the end of the conversation but then a couple of days later he was back to the same headspace.”

In March, Heinz ordered a selection of ropes from the internet and tried to hang himself in his apartment. He failed. When he came too, he called Adrienne, who was driving home from work. “I just tried to kill myself,” he told her. The family took him on a break to wine country and staged an intervention one evening after dinner. “He just kept saying, ‘I’m dead, I’m dead, I’m dead.’ We said, ‘We’re going to take you to the hospital. We’re going to get you the help you need.’” They had him committed in San Diego.

On 27 May 2015, a member of the Cambrian Genomics team opened up the laboratory after the long weekend, and discovered his body. Austen Heinz had hanged himself. He was 31.

Shortly before his death, Heinz had stayed with his best friend, Mike Alfred. “He felt like the whole world was against him,” Alfred told me. “He took it a lot more personally than I’d advise someone to.” I asked if there might have been any truth to the accusations of sexism. In 2009, he’d self-published a semi-fictional memoir that contained some unpleasant and juvenile talk of strippers and orgies. “It was not true at all,” Alfred said. “He had strong opinions about whether people were smart or not. He didn’t have a lot of respect for people that were dumb. But it wasn’t gender. He definitely was not a sexist.” The problem, said Alfred, was a lack of social sensitivity. “He wasn’t a person who sat around saying, ‘How can I make sure that what I’m about to say to this person comes across right?’ He would just say it.” “But isn’t that a common personality type in tech?” I asked. “I think so. There are a lot of really talented people that are really bad at reading others.”

Alfred also described Heinz as a “tormented soul.” Depression had long been a problem for him. Following his death, it was said he’d suffered from bipolar disorder, a claim that seems at least partly based on what he’d written in his semi-fictional memoir. Adrienne disputes this. “He never received a formal diagnosis of bipolar disorder,” she said, citing his medical records. “I was bothered that this was published and not fact-checked. The only formal diagnosis he received was major depressive disorder. Austen saw mental-health providers at various points in his early adult life. He was not mentally ill or depressed his whole life. It came in waves and his depression was usually triggered by a difficult and stressful life event.” Ultimately, she said, it was the media assault that tipped him into his final decline. “No one’s to blame for his death,” she said. “But make no mistake, I know for a fact that this is what initiated this depression episode.” He was not always a charming presence and could certainly come off as arrogant and dismissive. But there was no justice in the mobbing he endured.

Austen Heinz was, in many respects, a victim of the age of perfectionism. If he was the type of person who was more sensitive to signals of failure in his environment, then the environment in which he found himself was savage. Despite his achievements, despite his incredible vision, despite his unshakeable belief that his work would change the world, he became the tragic victim of a confluence of factors—a socially awkward person, an emotionally vulnerable temperament, in a vicious and often cruel social media environment. When I asked Adrienne if she’d describe her brother as a perfectionist, she nodded. “He struggled with the black and white thinking that can be part of that; catastrophizing—‘I’m going to be homeless, everybody will think I’m a failure’—mind-reading of what other people think. And so when he started running into difficulties with the possibility of running out of money, keeping all these folks employed, he just got stuck in some really severe thinking traps.”

Two academics I spoke to mentioned this especially unpleasant aspect of our times. “It’s something that’s becoming more salient,” Professor Gordon Flett, an expert in the dangers of perfectionism told me. “When a public figure makes a mistake there seems to be a much stronger, more intense and quicker backlash. So kids growing up now see what happens to people who make a mistake and they’re very fearful of it.” Professor Kip Williams, a social pain specialist said, “You see it on both sides, from the Right and Left. There are strong pressures to conform and an immediate response to disrupt or to ostracize people who disagree.”

The irony of the new digital world that’s enabled the rise of these kinds of incidents is that it relies for its success on some of our most ancient characteristics. We’re tribal, and we’re wired to want to punish, sometimes savagely, those who transgress the codes of our in-group. These are powerful and dangerous instincts that can easily overwhelm us, with tragic unintended consequences.