Long Read

Not All Dead White Men—A Review

How many people are in this “community”? What power do they enjoy? What is the extent of their influence?

A review of Not All Dead White Men: Classics and Misogyny in the Digital Age, by Donna Zuckerberg. Harvard University Press, October 8, 2018 (288 pages).

How To Be a Good Classicist

Donna Zuckerberg holds a PhD in Classics from Princeton University. Her older brother, Mark Zuckerberg, is the co-founder of Facebook. Dr Zuckerberg has arguably become the most influential scholar of Greek and Latin literature in America, thanks to Eidolon, the online journal which she founded in 2015.

Outside university departments of Classics, Eidolon remains obscure. It emphasises Greek and Roman culture in the modern world, frequently in relation to some aspect of popular culture. Articles tend to be written in an informal, ‘accessible’ style; though few obviously appeal to readers who are not aspiring academics or junior scholars. Eidolon accurately reflects the orthodoxy prevailing in contemporary universities: this is what you have to say, and how you should sound, if you want an academic job.

The best-known Eidolon article remains Dr Zuckerberg’s “How to Be A Good Classicist Under A Bad Emperor,” which has been discussed before in Quillette . Dr Zuckerberg insists that the political movement known as the “Alt-Right” poses a credible threat to classical studies (not to mention the rest of America), and thus ought to be strategically resisted by all principled scholars, teachers and students.

In the concluding chapter to her new book Not All Dead White Men: Classics and Misogyny in the Digital Age, Dr Zuckerberg details how she has been nastily attacked by online trolls for her explicitly ‘activist’ approach to classical studies in Eidolon, receiving “hundreds of anti-Semitic tweets and e-mails”, some of which are described in gruesome detail. Her nemesis Daryush Valizadeh, better known as the blogger and “Pick-Up Artist” “Roosh V”,

bragged to his followers that he knew where I and my family lived, but argued that no physical violence was necessary because he had already raped my mind.

It is curious to note just how far Dr Zuckerberg’s work has been shaped by her reactions to avowed personal enemies: Valizadeh turns out to be the most frequently-discussed author in Not All Dead White Men, with twenty-four works cited in the bibliography, and far more entries in the index than any classical writer.

Powers Of “The Red Pill”

Not All Dead White Men argues that the Alt-Right, or “Red Pill Community,” seems unduly fascinated with the Greco-Roman tradition, and uses classical antiquity to lend an air of prestige to its ideas. Dr Zuckerberg asserts that Donald Trump’s election in 2016 “empowered these online communities to be even more outspoken about their ideology.” She quotes Daryush Valizadeh: [Trump’s] “presence [in office] automatically legitimises masculine behaviours that were previously labelled sexist and misogynist.”

Dr Zuckerberg makes no claim that President Trump himself has any time for Greek or Latin texts, drawing attention instead to his better-read advisers, the former White House Chief Strategist Steve Bannon (who was fired seven months into the Trump Administration), and former Deputy Assistant to the President for Strategic Communications Michael Anton (who quit after fourteen months on the job). She notes: “those who frequent Red Pill message boards have embraced these two men as heroes.”

The relationship between the Alt-Right or “Red Pill Community” and political power is difficult to discern, as Dr Zuckerberg concedes:

It would be an exaggeration to say that the men of the Red Pill community are writing national policy. However, on some level, they seem to believe that they are influencing policy, and that belief has empowered them.

This group of men is thus both ‘empowered’ and impotent.

“The Red Pill Community”

Dr Zuckerberg’s subject is an uneasy coalition of groups that rarely meet in real life:

… the Alt-Right, the Manosphere, Men Going Their Own Way, Pickup Artists … exist under the larger umbrella of what is known as the Red Pill, a group of men connected by common resentments against women, immigrants, people of colour and the liberal elite.

The object of Dr Zuckerberg’s scrutiny exists largely on Reddit, and is distinguished by its consistent opposition to the principles of Intersectional Feminism. This community is further united by its tendency to form online attack mobs on social media: “these men are the ones coordinating attacks to send death and rape threats to outspoken feminists.”

The Alt-Right (or “Red Pill Community”) remains difficult to define strictly. Dr Zuckerberg relies on a self-reported survey of Men’s Rights Activists (cited in Stephanie Zvan, “But How Do You Know the MRAs Are Atheists,” 13th April 2014:) to venture that “more than three quarters of these men are white, heterosexual, politically conservative, have no strong religious affiliation, and are between the ages of eighteen and thirty-five.”

This characterisation is somewhat misleading. The survey of Men’s Rights Activists cited by Stephanie Zvan lists respondents who are 98% white, 94% non-religious, 84% strongly conservative, and 87% between the ages of seventeen and twenty.

Zvan’s corrected figures still suggest that Men’s Rights Activists are 92% white, 87% male, 35% aged seventeen to twenty (with a median age of twenty), and 70% non-religious. There are no figures given for sexual orientation; in the cited self-reported survey, 7% of respondents supported same-sex marriage; a slightly smaller number supported trans peoples’ rights. At least it is clear that ‘straight’ white men must make up a majority of Men’s Rights Activists. Though Men’s Right’s Activists do not make up the entire “Red Pill Community”.

Questions that Dr Zuckerberg declines to pose in Not All Dead White Men include: How many people are in this “community”? What power do they enjoy? What is the extent of their influence? Over whom, and over what? How many of this book’s subjects turn out simply to be frustrated, isolated twenty-year-olds with limited professional prospects?

Dr Zuckerberg is well aware that the “Red Pill Community” she describes is made up of warring factions: Pick-Up Artists, Men’s Rights Activists and Men Going Their Own Way vehemently disagree on how to respond to Intersectional Feminism; nonetheless:

They [all] feel compelled to position themselves as the inheritors of the classical tradition and how the ancient world validates one of their most cherished, deeply-held beliefs: that all women throughout history share distinct, immutable qualities that make them promiscuous, deceitful and manipulative.

Dr Zuckerberg connects these groups to the Alt-Right by identifying a further unifying bond: they all hate Social Justice Warriors (SJWs). She quotes Darius Valizadeh’s definition of this term:

Social justice warriors believe in an extreme left-wing ideology that combines feminism, progressivism and political correctness into a totalitarian system that attempts to censor speech and promote fringe lifestyles while actively discriminating against men, particularly white men.

Guidance For Resisting

Not All Dead White Men claims two distinct purposes. The first is as intellectual history, to show how “the men of the Red Pill use the literature and history of ancient Greece and Rome to promote patriarchal and white supremacist ideology.” The second is as a sort of how-to kit or self-help guide for Intersectional Feminists:

As soon as a woman self-identifies online as a feminist, she is likely to find herself in a hailstorm of abusive tweets and e-mails from the men who frequent Red Pill websites. Understanding their ideology and tactics for online intimidation can help lessen the impact of that abuse.

At the end of “Arms and the Manosphere,” the first chapter of Not All Dead White Men, a section entitled “The Red Pill Toolbox” attempts to delineate the means used by members of the “Red Pill Community” to harass Intersectional Feminists. The main instruments in the “Red Pill Toolbox,” as outlined here are: ‘gaslighting;’ “the appropriative bait-and-switch” (sc. misuse of “the language of systemic oppression from social justice movements;”) “misuse of the language of scholarly interpretation;” and false equivalence.

Bigotry in Latin and Greek

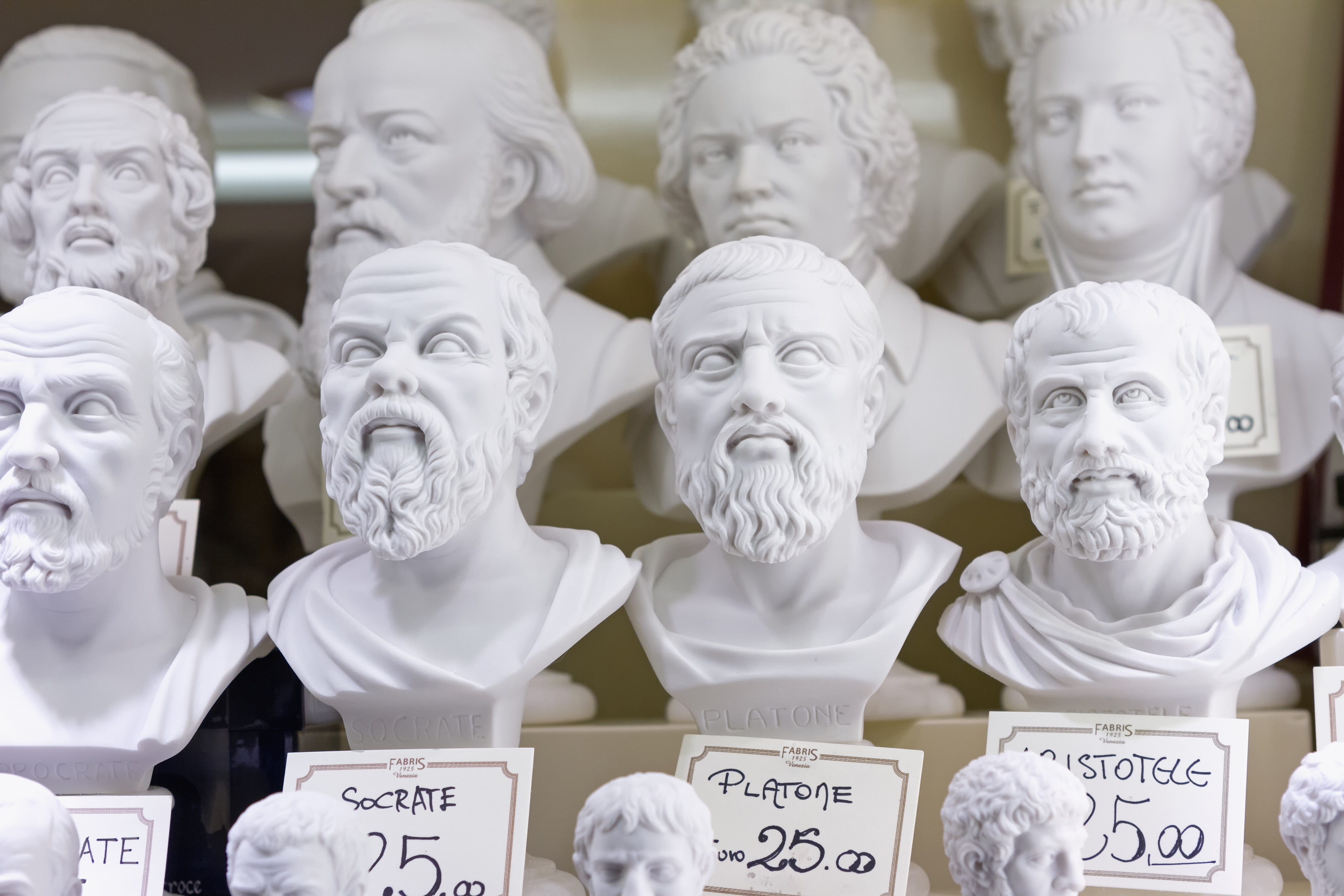

Dr Zuckerberg begins her book by describing posters for the neo-Nazi group “Identity Evropa” [sic] that were posted on college campuses late in 2016, and made use of black and white photos of classical or ancient-looking statues. It may be objected that a photograph of the Apollo Belvedere downloaded from the internet by an obscure, dwindling collection of white separatists may be safely ignored by scholars of ‘classical reception’. Not so:

Political and social movements have long appropriated the history, literature and myth of the ancient world to their advantage. Borrowing the symbols of these cultures, as the Nazi Party did in the 1940s, can be a powerful declaration that you are the inheritor of Western culture and civilisation.

Being a scholar of literature, Dr Zuckerberg concentrates more on texts than images. She finds that ancient Greek and Latin writers are often openly misogynistic; or at least what they write is frequently at odds with the precepts of contemporary Intersectional Feminism.

Dr Zuckerberg has uncovered an anonymous commentator on Reddit who lets his readers know:

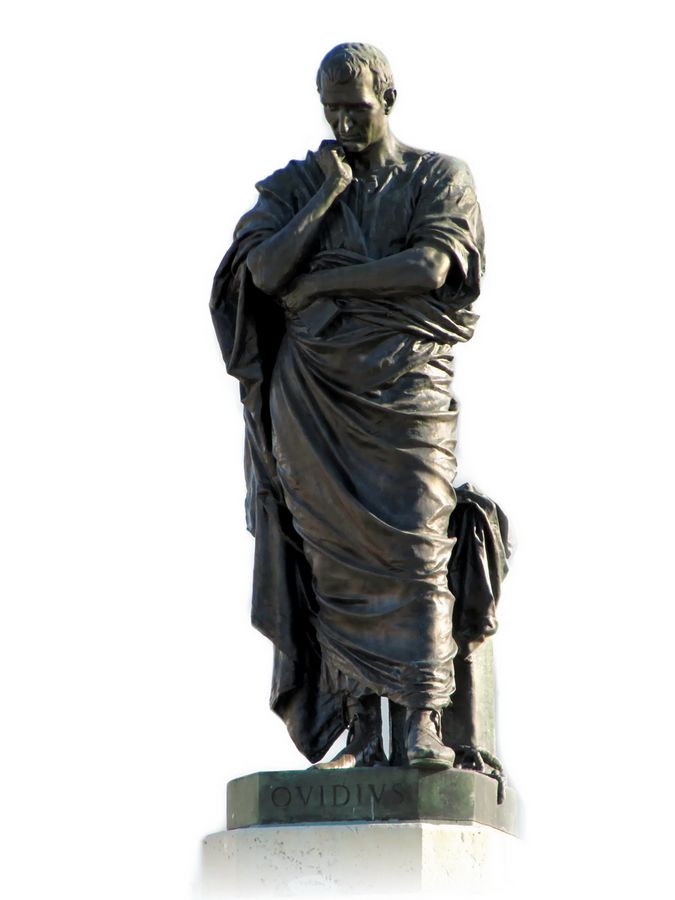

“I am a classicist by training, PhD the whole nine yards. The Greeks and Romans were Red Pill in the extreme.” With this in mind, she surveys selected thoughts, views and statements by Hesiod, Semonides of Amorgos, Xenophon, Aristotle and Juvenal that have been quoted with approval by members of the “Red Pill Community;” though the bulk of Not All Dead White Men deals with the Roman poet Ovid, the Athenian dramatist Euripides, and Stoic philosophy generally.

Dr Zuckerberg is sensitive to the possibility that Stoic philosophy may be inherently misogynistic:

… as Professor Martha Nussbaum has pointed out, all of these texts discussing the possibility of female virtue are fundamentally antifeminist by virtue of being aimed at male audiences.

She almost absolves the Roman writer Musonius Rufus from charges of misogyny, even though his work has appealed to at least one Alt-Right blogger, on the grounds that his thought was fairly egalitarian by the standards of ancient Stoic philosophers. Cicero and Seneca are too irredeemably sexist in their attitudes to merit the same excuse. Even the Latin word for ‘virtue’ derives from the Latin word for ‘man’.

Ovid’s is a harder case. His mythological epic the Metamorphoses (published in AD 8) features numerous instances of sexual violence. Certainly Ovid’s dark, provocative sense of humour is often more shocking than amusing. His Ars Amatoria (‘Art of Love’), purportedly an instruction manual on seduction, is clearly satirical; but how, and against whom? Ovid flippantly, cynically mocks everyone, including other ancient poets. Yet ‘Pick-Up Artists’ purportedly take his tongue-in-cheek advice seriously. Is Ovid himself a misogynist, or is his work a vehicle for others’ misogynistic fantasies? Dr Zuckerberg never makes up her mind on this issue.

Dr Zuckerberg’s views on Euripides’ tragedy Hippolytus (428 BC) are even more conflicted. The title character in Hippolytus is a prince who has offended the goddess Aphrodite by renouncing sex and marriage; Aphrodite punishes him by making his stepmother Phaedra fall in love with him. When Hippolytus finds out, Phaedra hangs herself, leaving behind a letter in which she falsely accuses Hippolytus of raping her.

Professor Edith Hall calls this tragedy “a play of exquisite poetic beauty but toxic ideology […]. Every performance constitutes another ‘proof’ of the mass delusion that information imparted by women is unreliable.” In Dr Zuckerberg’s reading of this position:

[Professor Hall] does not go so far as to say that we should stop studying or performing these plays, or that actors who play the role of Phaedra are responsible for rape victims’ not being believed—but the implication is clear [that] … she believes women would be believed more readily if the play did not exist.

Dr Zuckerberg reluctantly rejects Professor Hall’s position, on the grounds that “what Phaedra’s story actually shows is that male terror of false rape allegations is and was largely unfounded.”

Hippolytus can still be read provided an ideologically satisfying justification can be found. What happens to ancient texts that cannot pass the censors?

Ancient Rape Culture

“How to Save Western Civilisation,” the fourth chapter of Not All Dead White Men, begins by mentioning a 2017 article entitled “The Problem of False Rape Accusations is Not Going Away.” The author, Christopher Leonid, seems to be the only member of the “Red Pill Community” who has written at length about Hippolytus myth. Yet false rape allegations are supposedly a major preoccupation of these antifeminist writers. Thus Dr Zuckerberg decides:

Despite the lack of attention paid to Hippolytus and Phaedra in the Red Pill, I believe it is worth reading the myth in the context of Red Pill ideology.

In other words: these men would have been fascinated, if only they had read Euripides’ play.

The absence of solid material to write about allows Dr Zuckerberg’s mind to wander freely. In the section “Rape Myths and Myths about Rape,” she speculates about rape allegations, false rape allegations, and the definition of rape itself:

Since the ultimate power to decide what qualifies as sexual assault falls in the hands of the government, this discussion of terminology is really a discussion about politics. To be more precise, it is a discussion about sex under patriarchy, because the feminist definition of rape and the Red Pill definition of rape are predicated on assumptions about how patriarchal our society is and how patriarchal it should ideally be.

Eventually this leads to open questions about due process:

One of the core beliefs of our legal system is that defendants are innocent until proven guilty. But many feminists would like to believe and support those who claim to be the victims of sexual assault. So how should we reconcile ourselves to the fact that these two stances are fundamentally irreconcilable?

After many words and pages, Dr Zuckerberg drops an unexpected bomb:

I think few would dispute that ancient Athens and Rome were indeed societies that severely restricted female autonomy. So was all sex in the ancient world rape?

This leads her to ask whether ancient Greece and Rome were rape cultures. She decides that they were. In fact:

… Herodotus’s Histories, the foundation on which the study of European history is built, begins with a series of rapes—or abductions, since in Herodotus’s text the line between rape and abduction … was not sharply defined.

This speculation rises to an extraordinary climax: after describing the mythical events that that led to prince Paris’s abduction of the beautiful Helen, wife of Menelaus of Sparta, which resulted in the Trojan War, Dr Zuckerberg concludes:

Is Herodotus describing what we would call a rape culture? By the definition I provided above, it would seem so, especially when he casually reports the Persian opinion that women are responsible for and co-conspirators to their own abductions (“if they did not want to be abducted, they would not have been”) and Paris’s blithe confidence that abducting Helen will result in no serious consequences. In fact, Herodotus is indirectly participating in two separate rape cultures. The first is the world of myth, where rape is an extremely common occurrence. The second is the world of fifth-century Greece, where the author’s blasé attitude toward punishing an enemy by raping one of that enemy’s countrywomen is not remarkable, but typical.

Apparently you can participate in a rape culture by describing one in a book. You can even participate simply by living in a society where rapes sometimes go unpunished. But is it really fair to call the mythical culture of the Greek ‘heroic age’ a rape culture, when Paris’s abduction of Helen led to an international military invasion, a siege that lasted a decade, the destruction of the city of Troy, and the slaughter or capture and enslavement of the vast majority of such Trojans as had not already been killed during the war?

Whether it is completely fictional or only largely so, this society can hardly be considered a “social group that normalises rape to the degree that consequences for rapists are minimal or non-existent and punishing rapists is seen as more barbaric than rape itself.”

What does any of this have to do with the “Red Pill Community”?

Problems of Method

Throughout Not All Dead White Men, Dr Zuckerberg implies that the views of members of the “Red Pill Community” cannot withstand sustained intellectual scrutiny:

Red Pill analyses of ancient texts may seem simplistic and misguided to us. In fact, they [sic] are not really producing analyses at all. Their interpretations of the Classics should be approached, not as readings of the ancient world, but rather as aspirational representations of the world they wish we inhabited. They idealise a model for gendered behaviour that erases much of the social progress that has been achieved in the past two thousand [sic] years –– and they are using ancient literature to justify it.

In other words, the ancient world as apparently glimpsed through Latin and Greek texts provides a sort of fantasyland for the “Red Pill Community” to play around in whilst daydreaming. If this is true, then it is hard to see how this community’s use of ancient literature, philosophy and history deserves any attention at all.

Not All Dead White Men, despite being published by a major university press, is more of a polemic than an academic study. The standard of citation is variable, and Dr Zuckerberg is not always a careful or thorough researcher.

Superficially the bibliography appears scholarly; though the sources cited are frequently exercises in critical theory or ideological interpretation rather than genuine scholarship. On major classical subjects (Stoicism, Ovid, Euripides) Dr Zuckerberg fails to cite standard texts, commentaries or basic resources. She is not obliged to survey secondary literature for a study of this nature; though the range of materials included in the list of references is questionable. Some items in the bibliography are far beyond any classicist’s expertise, and only tangentially relevant to this research (for example, articles in the British Columbia Medical Journal, the Journal of Clinical Psychology and the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology).

As for sources on the “Red Pill Community:” Dr Zuckerberg has read deeply in a narrow range of materials including The Daily Stormer, Return of Kings, Darius Valizadeh’s personal website, and various blogs and Reddits. It seems fair to comb journalistic sources such as Vox, Buzzfeed, the Daily Beast, the Guardian and Mother Jones for material on the Alt-Right. But academic studies are available, not least George Hawley’s illuminating Right-Wing Critics of American Conservatism (University Press of Kansas 2016), and its sequel Making Sense of the Alt-Right (Columbia University Press 2017). Think tanks such as Political Research Associates have also produced valuable reports, all of which Dr Zuckerberg has ignored.

Some materials are unjustly misrepresented. Dr Zuckerberg has every right to disagree with controversial academics such as Allan Bloom (author of the 1987 bestseller Closing of the American Mind) and Victor Davis Hanson (long despised by progressive classicists for co-authoring the 1998 polemic Who Killed Homer?). But to conflate their views with those of the “Red Pill Community” verges on libel. Evidently Dr Zuckerberg has read neither Closing of the American Mind nor Who Killed Homer? even though both books are listed in her bibliography. She side-swipes in passing:

…in the 1987 book The Closing of the American Mind, Allan Bloom had written that “the latest enemy of the vitality of classics texts is feminism.” His use of the word vitality suggests that ancient texts are somehow not as “alive” for feminists as they are for misogynists.

It would have taken only a few minutes to look up this line in Bloom’s widely-available text, read the (admittedly long-winded) six-page chapter in which it was written, and avoid this misreading. No alert reader is fooled by the precision with which “page 65” is cited in a footnote. The (mildly liberal-left, staunchly classical-liberal) classicist Bernard Knox is at least allowed the dignity of a longer quotation to speak for himself before Dr Zuckerberg associates him with the “Red Pill Community.”

Philosophical Issues

On ancient philosophy, Dr Zuckerberg is out of her depth, and fails to provide a consistent account of its principles or characteristics in Not All Dead White Men, either as developed by ancient writers, or in its watered-down “Red Pill” form. It might have been wiser simply to refer the reader to the relevant articles in the Internet Encyclopaedia of Philosophy or online Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy.

Dr Zuckerberg relies heavily on The Hellenistic Philosophers (edited by A. Long and D. Sedley; 2 vols.; Cambridge University Press 1987). Although an excellent resource for advanced undergraduates, this seems inappropriate for a study of how autodidacts with no command of Latin or Greek, and little to no instruction in any area of classical studies, make occasional use of Stoic philosophical texts in translation to justify their anti-feminist positions.

Dr Zuckerberg might have consulted the various ‘Cambridge Companions’ to the Stoics, Seneca and Cicero to clarify issues related to the reception of Stoicism. Instead she relies on popular biographies and literary journalism for enlightenment on how various Stoic philosophers have been received (cf. footnote 18 to chapter two, where review articles from the New Yorker and New York Review of Books are cited; then the books reviewed in those articles are used as authorities in footnote 19; for additional support Dr Zuckerberg relies on Robert Hughes’s 2011 Rome: A Cultural, Visual and Personal History, which is vividly written, but spoilt by so many basic factual errors that it might as well be classified as a fictionalised memoir).

Dr Zuckerberg is less thorough on the phenomenon of self-help books based around Stoic principles. She pays particularly close attention to the bestselling writer Ryan Holiday, whose books on Stoicism as a “life hack” are said to enjoy a certain vogue in Silicon Valley. Holiday’s explorations of Stoicism include The Obstacle is the Way: The Timeless Art of Turning Trials into Triumph (2014) and Ego is the Enemy (2016). Dr Zuckerberg admits that Holiday is in no way a member of the “Red Pill Community”, though insinuates that he is in some way associated it, because his works have been praised on “Red Pill” websites.

Other than a few pieces on Daryush Valizadeh’s (now-defunct) website Return of Kings, there turns out to be little direct “Manosphere” engagement with Stoic philosophy in any form. Dr Zuckerberg is reduced to pointing out how Steve Bannon is said to have once been fond of quoting from the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius.

Textual Difficulties

Not All Dead White Men inevitably features quotations from ancient literature. Dr Zuckerberg has translated the bulk of these herself, though provides no details of the editions consulted for key Latin and Greek texts. The bibliography lists nothing for Catullus’s poetry, or Euripides’ Hippolytus; for Ovid, she lists two obscure recent scholarly translations, as well as the English poet Ted Hughes’s 1997 Tales From Ovid, a free-form improvisation on Ovid’s Metamorphoses that is hampered by the author’s inability to read the original text in Latin. Dr Zuckerberg inexplicably quotes from this ‘translation’ when discussing the rape of Proserpina; Hughes flagrantly misrepresents Jupiter’s speech in the relevant passage (Metamorphoses V.523-532). Why did Dr Zuckerberg not supply a faithful, literal translation of Ovid’s words here? The Latin is hardly difficult.

Perhaps Dr Zuckerberg is aware of her own shortcomings as a translator. Her versions of Hesiod, Juvenal, Ovid, Propertius and Catullus in Not All Dead White Men are disappointing. She has not translated her chosen excerpts into English that sounds like the English she otherwise writes. When Dr Zuckerberg translates ancient verse, her diction becomes stiffly archaic; her renditions of Catullus in particular sound as though English were not her first language.

Style is less of a problem than accuracy. It is alarming to see how Dr Zuckerberg mistranslates some simple lines from Ovid (Ars Amatoria III. 765-768). She then accuses Ovid here of advising women that “if they get drunk they deserve to be raped.” Surely anyone who reads the Art of Love, even in (accurate) translation, should be able to see that this reading is simply not borne out by the text.

Even worse is Dr Zuckerberg’s reading of a passage from the same poem:

One might wonder if Ovid is more interested in women as objects of seduction or as readers and students (and buyers) of his poems. He even explicitly advises women that, if they wish to appear educated, they should also familiarise themselves with [his earlier works] the Amores and Heroides (Ars Amatoria III.339-346). Being able to claim a female audience, for Ovid, must have been primarily a matter of social capital and posture.

Dr Zuckerberg should re-read Ars Amatoria III.311-349, in English if necessary, to see how dishonestly she has portrayed Ovid’s work here. Or does Dr Zuckerberg simply not understand that Ovid is merely saying here that he hopes his works will be read in the future, and grant him a sort of immortality, at the end of a passage which emphasises the importance of music and song in charming the opposite sex?

As for Greek: Dr Zuckerberg does not seem in general to comprehend that a given word may have several meanings, not all of which are relevant when that word is used in a particular context. True, neither the Greeks nor the Romans had a single term which corresponds perfectly to our modern usage of the word ‘rape.’ This does not mean that the ancient world lacked any coherent concept of sexual violence, or that these crimes were ignored, or disregarded. Quite the contrary, in fact.

In discussing the historian Herodotus, Dr Zuckerberg implies that “in Herodotus’s text the line between rape and abduction … was not sharply defined.” She claims this in part because the noun ἁρπαγή (harpagē) is listed in the Liddell-Scott-Jones Greek lexicon as meaning ‘seizure’, ‘robbery’ or ‘rape.’ But in context it is invariably clear which of these is meant. The verb ἁρπάζω (harpadzō) on the other hand is used to mean ‘ravish’ (as the Victorian lexicographers put it) only in rare later instances; otherwise it means ‘seize,’ ‘snatch,’ ‘abduct,’ ‘carry away’ or ‘overpower.’ In the passages under discussion, Herodotus never uses this noun or this verb to mean ‘rape.’ This is not because he is an exponent of ‘rape culture;’ rather, he is talking explicitly and obviously about abductions and kidnappings, not rapes.

Questions of Interpretation

Dr Zuckerberg relies heavily on commentators and literary critics, particularly for Ovid, where a single collection of essays (The Art of Love: Bimillennial Essays on Ovid’s Ars Amatoria and Remedia Amoris, edited by Roy Gibson, Steven Green and Alison Sharrock, Oxford University Press 2007) all but dictates the interpretation of the text. Then again, Dr Zuckerberg’s own engagement with these texts is far from profound:

Even though it was published two thousand years ago, the Ars Amatoria can feel very relevant to today’s world. But it is ultimately a poem that Ovid intended for his time, not for all time. The superficial similarity between his suggestions for how to avoid buying your [lover] expensive gifts and advice on seduction blogs for how not to buy a girl drinks or spend more than twenty dollars on a date is misleading. Treating Ovid as “the original [Pick-Up Artist]” –– or claiming, as [author of The Game Neil “Style” Strauss] did on Reddit, that “what works has always been the same throughout history, from Ovid’s writing on seduction to today” –– is difficult to justify from a theoretical perspective. Although there are undeniable similarities, most are superficial, and the cultural conditions that shaped Ovid’s text are entirely different from those that shape the seduction community.

Part of the joke of Ovid’s ‘didactic’ poetry about seduction is its patent uselessness. The Art of Love is about as effective as an instruction manual for would-be lovers as Vergil’s stylised, erudite, highly polished Georgics is for would-be farmers. Dr Zuckerberg realised this too late; her chapter on Ovid ends:

Unfortunately, Ovid’s text is more useful to pickup artists in theory than it is in practice. In his book review, [Darius] Valizadeh calls it “a chore to get through.” [James C.] Weidmann assesses it as “pretty uneven in its advice.”

In other words, Ovid has minimal influence over the “Red Pill Community:” the few within it who have read his work are not interested.

As a literary critic, Dr Zuckerberg sometimes lacks a sense of proportion: for example:

Like Herodotus, the Roman historian Livy uses rape as a major narrative device for shaping history.

Only thirty-five books survive of Livy’s 142-volume history of Rome. But epitomes, fragments and lists of contents exist to provide a reasonable idea of what is missing. It is false to claim that rape is a “major narrative device” shaping this work except perhaps in the very first book, where instances of rape are limited to the infamous Rape of the Sabine Women (chapters 9-13) and the rape of Lucretia (chapters 57-59).

Eight out of sixty chapters appears to be a significant proportion of the narrative, to be sure. The rape of Lucretia helped precipitate the overthrow of the Roman monarchy. But to claim that rape is a mere narrative device is itself outrageous; to claim further that Livy’s history is shaped by anything other than war, politics, diplomacy and religion is insupportable.

Dr Zuckerberg also has curious notions about evidence. She cites a speech by the Athenian orator Lysias as a straightforward source for ancient Greek attitudes towards “rape and female subjectivity.” Lysias supposedly wrote this speech, “Against Eratosthenes,” for a man named Euphiletus, who was on trial for murdering a man he caught in bed with his wife.

This is not a straightforward recital of contemporary Athenian principles, but a speech of self-defence for a man accused of murdering his wife’s lover. Under threat of execution, Euphiletus will naturally claim that adultery is a worse crime than murder. If Lysias’s speech is a reliable a guide to fourth-century BC Athenian morality, then we look forward to trusting Harvey Weinstein’s defence team to tell us all we need to know about modern American morality, when the disgraced film producer is put on trial in New York for alleged incidents of rape, criminal sex acts, sex abuse and sexual misconduct.

At least Dr Zuckerberg’s summary of Euripides’ Hippolytus is reliable, even if the quoted sections of Greek text are awkwardly translated. But even this is uneven and incomplete, and fails to convey any sense of the play’s sensitivity, subtlety and intellectual complexity, to say nothing of its literary qualities. The summaries of Ovid’s and Seneca’s retellings of this story are unfocussed and haphazardly structured; there is no clear reason why Dr Zuckerberg has bothered to write about these.

Historical Consciousness

It would be unfair to judge Dr Zuckerberg too harshly for not having mastered historical materials related to subjects that have nothing to do with ancient literature.

Still: early in the book she brings up the Nazi appropriation of the Greco-Roman cultural tradition as a parallel phenomenon to “Red Pill Community” uses of similar materials. But classical Greek and Roman imagery, tropes and ideas do not predominate in Nazi propaganda. Italian fascism on the other hand is explicitly restorationist, appropriating ancient Roman symbols as one of many means of associating their movement with the glory, prestige and grandeur of the Eternal City and the Roman Empire. The ‘fasces’ itself is a symbol of power predating the advent of the Roman Republic.

Some exploration of Italian fascism might have been highly productive, particularly since some current neo-fascist movements in continental Europe have begun to revive this association with the classical tradition. But Dr Zuckerberg ignores all this.

In another section, Dr Zuckerberg describes “triple-parentheses echoes”—((( )))—as “an anti-Semitic dog-whistle used by the Alt-Right as the virtual equivalent of the yellow Jewish star badge used in Nazi Germany”.

The “echo” symbol is indeed an anti-Semitic ‘dog-whistle’ device; thus it is wrong to compare it to the yellow-star badge. Identification badges were imposed on Jews, first in Nazi-occupied Poland, then other occupied or annexed states, until German Jews were finally compelled by law to wear them in September 1941. Dr Zuckerberg’s comparison would make sense if this “echo” symbol were imposed by force on Jews to identify them. But a “dog whistle” is a covert indication, meant to escape detection by authorities. The Alt-Right lacks the power and influence to make Jews or anyone else do anything. As Dr Zuckerberg admits in the conclusion to Not All Dead White Men:

Realistically speaking, their numbers are too few and their views too extreme for the Red Pill to have any significant political impact.

Minor Errata

Not All Dead White Men features a “Glossary of Red Pill Terms” for readers who are unclear on the definitions of “meme,” “troll” and “GamerGate;” the last of these is defined as “a movement to lessen the impact of social justice movement [sic] in the video game and science fiction communities.” The bibliography should have been separated to distinguish scholarly literature from blog posts, magazine articles and opinion pieces. Though the index seems to be generally reliable. All in all, Harvard University Press has demonstrated questionable competence and judgment in publishing Not All Dead White Men in its current state, when the manuscript could have gone through at least another draft to remove repetitions and inconsistencies, and correct Dr Zuckerberg’s tendency to ramble around her chosen subject.

Not All Dead White Men fails to define its subject clearly, and does not succeed in its stated purposes, either as intellectual history or a guide to helping feminists protect themselves from online harassment. Nor does Dr Zuckerberg succeed in demonstrating that the Alt-Right or “Red Pill Community” has much time for classical Greece or Rome. She admits:

Red Pill Classics tends to be relatively superficial, relying on the uninterrogated assumption that its members are the natural inheritors of the legacy of classical antiquity.

Even this overstates the case radically. The subjects of this volume, on the evidence presented by Dr Zuckerberg, are scarcely conscious of classical antiquity, except as a vague source of occasional imagery. These men do not read deeply in ancient texts, nor are they interested to do so.

Distinguished classicists including Professor Emily Wilson (University of Pennsylvania), Professor Paul Cartledge (University of Cambridge), Professor Gregory Nagy (Harvard University) and Professor Joy Connolly (Provost and Interim President of the Graduate Centre at City University of New York) have all publicly praised Not All Dead White Men; their endorsements can easily be found on the book’s publicity page on the Harvard University Press website

What they say does not match the contents of the book.

Conclusion

Not All Dead White Men is not recommended.