Top Stories

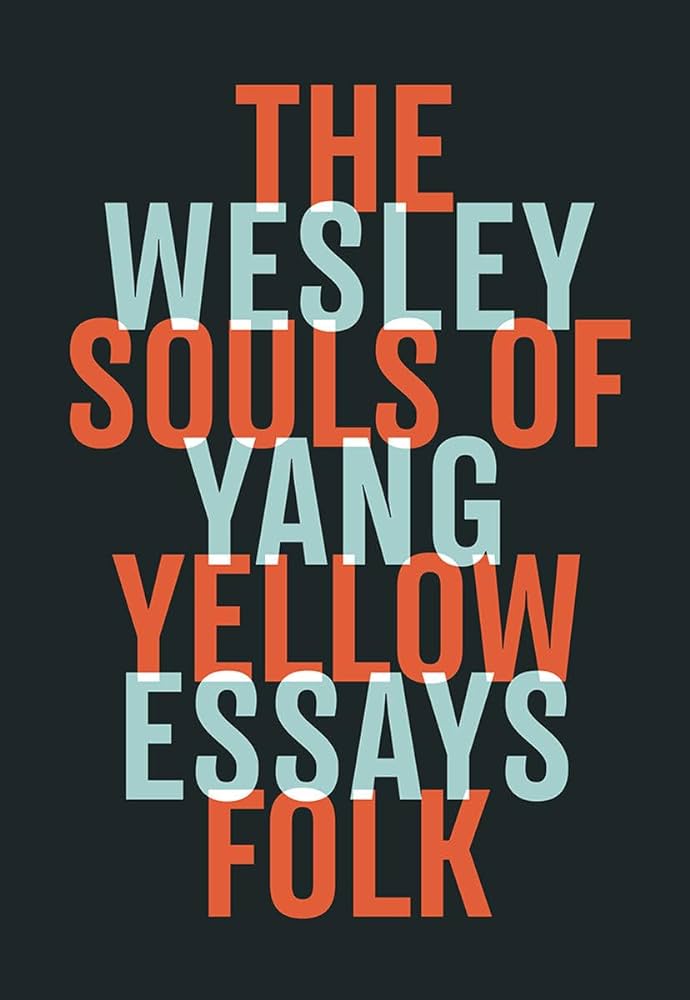

The Souls of Yellow Folk—A Review

Collectively, the essays paint a fascinating and disturbing picture of pre-dystopian anomie and dissolution.

A review of The Souls of Yellow Folk by Wesley Yang. W. W. Norton & Company (November 2018), 256 pages.

Wesley Yang’s longform essay “The Face of Seung-Hui Cho” was first published in the small magazine n+1 in the early months of 2008. At the time Yang, who was in his early 30s, seemed to be a typical young New York writer. He had published an assortment of short pieces, mostly about books, for places like New York, Salon, and the New York Observer. He wasn’t a “name” yet, but he was well-known enough that one of the editors of n+1 thought of him when they were looking for someone to write about Cho, the Korean-American student who’d killed 32 people and wounded 17 during his shooting rampage on the campus of Virginia Tech.

“I resented the implication of his request,” writes Yang in the introduction to his new collection of essays, The Souls of Yellow Folk. “The implication was that there was something about that episode that would be particularly salient to me. …The implication was that we shared something in common, the Virginia Tech killer and I. … I resented the implication because it was true.”

The piece that Yang dredged up out of this resented truth, which leads off the new book, was extraordinary. Funny, brutally smart, vulgar, and self-lacerating, but also bluntly confident in its judgments. Seung-Hui Cho wasn’t just Wesley Yang, he was millions of lonely young men who felt unloved, unseen, and unvalued in contemporary America, many of whom burn with ressentiment, and some of whom, it was becoming clear, would make the rest of us pay for their desperation. Re-reading the essay now, a decade later, its themes resonate even more powerfully now that we’ve all been overtaken by the sad angry lonely man truths Yang was exploring a decade ago.

“Cho imagines the one thing that can never exist,” writes Yang, “…an army of other losers like himself, denied recognition and rendered invisible, who would someday attain class consciousness and leave behind their abjection through violent, coordinated action to subdue the world to their will, or die fighting.”

The essay goes on like this for about 10,000 words, each page scintillating with insight and intelligence. An abbreviated list of the things about which the essay has exceptionally interesting things to say would include: Korean faces; indie romantic comedies; young homosexuals; Wayne Lo; Seung-hui Cho; “brown-toned South American immigrants that pick your fruit, slaughter your meat, and bus your tables”; the middle class people who would never date them, and the impossibility of acknowledging this fact; the understandable revulsion of pretty white girls toward creepy-seeming Korean boys; bad early ’90s grunge rock; the hypocrisy of poet Nikki Giovanni; Yang’s own damned self; and Yang’s old college acquaintance Samuel Goldfarb, of whom Yang writes: “He was ugly on the outside, and once you got past that you found the true ugliness on the inside.”

There aren’t many essayists alive today who can sustain the level of brilliance Yang maintains in the essay for as long as he does. Zadie Smith can do it. Dave Hickey and Joan Didion could do it once, but are too old now. David Foster Wallace could do it, but although he should be alive, he is not. Ta-Nehisi Coates looked like he was on his way toward being able to do it, but he made other choices. A few other writers, maybe, but not many.

The essay doesn’t just teem with sentence-level excellence. Through all the micro-level fascination Yang has a larger point to make about what it is like to be an unlovable young man in America, a loser in the sexual and cultural marketplace, and the ways in which that loserdom intersects with and reinforces the experience of Asian-American-ness.

He is also enacting, or asserting, some version of what an alternative Asian-American identity might look or sound like, fierce in its refusal to submit to the expectations that anyone would impose on it, rife with ambivalence and ambiguity, embracing of complexity and contradiction.

Back in 2008, the essay seemed to ensure that Yang would be an important American writer. He would get a book deal. The big magazines would give him thousands of words, and dollars, to do his thing, and he would appear on panels in Aspen and Brooklyn. He would be the last thing he could have ever imagined, one of those glowing figures who are the object of resentment and envy of the unloved masses. Such trajectories aren’t usually predictable from one essay in a small magazine, but in this case it was.

But then Yang disappeared. He didn’t literally disappear, of course. The new collection is a record of that fact. With the exception of 2012, there is a piece from every year between then and now, including two essays from late 2017. Most of these pieces were originally published in high profile publications, and one of them won a National Magazine Award.

But Yang the writer on the fast track to literary eminence didn’t materialize. He only alludes to the reasons for this in The Souls of Yellow Folk, and in some work that isn’t collected here (including a recent profile of Jordan Peterson, in which he wrote,“I first came across Jordan Peterson in late 2016. I had been ensnared in a destructive familial ordeal that consumed some of the most important years of my career and put a strain on my marriage. I was unable to complete a manuscript for a book that I had been contracted to write. I had assignments I couldn’t finish. I was, in other words, exactly the sort of person whom Peterson’s message is optimized to reach.”). The relevant fact, though, is that for six or seven years he wasn’t able to dedicate himself to writing and building his career. That The Souls of Yellow Folk is as good as it is, despite this, is testament to how good Yang is.

The book fluctuates in its quality, but only between good and extraordinary. He’s only good on chef Eddie Huang, rebel hacker tragedy Aaron Swartz, sex in New York City, Britney Spears, pick-up artist Neil Strauss, leftist thinker Tony Judt, and bigthink political theorist Francis Fukuyama. He’s extraordinary on Seung-Hui Cho, tiger mom Amy Chua, and—in the book’s last section—identity politics in the age of Trump.

Collectively, the essays paint a fascinating and disturbing picture of pre-dystopian anomie and dissolution. The lonely and angry and oversensitive young men who will, by 2035 or so, have coalesced into roving tribes of bandits and revolutionaries, are—at the moment—only coalescing and pillaging online. They’re self-identifying and tribalizing as masters of seduction rather than masters of destruction. They’re killing themselves, not others, or killing as loners rather than as bands of brownshirts. The identity politics presently disfiguring our multi-racial democracy is, for the moment, mostly a phenomenon of social media, the campuses, and certain sectors of the media. Its influence is largely a reflection of the passion and rhetorical savvy of its adherents rather than their numbers or their actual capacity to persuade people outside of their communities. But the writing’s on the wall.

“Social media has proven to be, among other things, a remarkably efficient means to inject novel ideas,” writes Yang in the book’s final essay, “into a public sphere occupied by members of the media, activist, and intellectual classes, who use it, among other things, to coordinate an ever-advancing consensus about what being antiracist entails. There one can watch in real time as the unfolding of the internal logic of various ideological tendencies emerge, evolve, and reach their terminus. One handy rule of thumb is that any accusation or charge made as a half-ironic provocation in May will be avowed with earnest conviction in December and chanted by activists the following April.”

That the book ends at such a pitch of intellectual intensity is significant. It suggests that for whatever combination of personal, economic, intellectual, and larger cultural reasons, Yang is back. It also suggests that there is hope yet for a humane, liberal, complex alternative to white nationalism and identity politics (or Britney Spears and Neil Strauss). The liberalism that runs so deep in the national psyche may continue to exert a fundamental constraint on the extremism, idiocy, and violence that also, alas, run pretty deep.

In a number of hostile reviews of The Souls of Yellow Folk, Yang has been criticized for the presumptuousness of his title. It’s a half- or two-thirds-fair criticism. This is not an analog to W.E.B. DuBois’s The Souls of Black Folk. A good chunk of the pieces in the book don’t even address Asian-Americanness. Those that do are overlapping rather than integrated or coordinated in their arguments. It’s not a wholly fair critique, though. There is an argument, implicit and occasionally explicit in the book, about the role that the souls of yellow folk may end up playing in the fate of the republic. It’s an unfinished argument, for which Yang must bear responsibility. Nevertheless, it’s interesting and challenging and demands consideration, as almost everything Yang writes does.

“In an age characterized by the politics of resentment,” he writes, “the Asian man knows something of the resentment of the embattled white man, besieged on all sides by grievances and demands for reparation, and something of the resentments of the rising social-justice warrior, who feels with every fiber of their being that all that stands in the way of the attainment of their thwarted ambitions is nothing so much as a white man. Tasting of the frustrations of both, he is denied the entitlements of either. This condition of marginality is both the cause and the effect of his erasure—and perhaps the source of his claim to his centrality, indeed his universality.”

I don’t know if that’s true, globally. What is clear, however, is that Yang’s refreshing perspective feels important. He is one of the essential writers we have right now and we are lucky to have him.