Classical Liberalism

Individuals and Symbols

Whenever a political movement ceases to see people as individuals, and rather sees them as symbols of a class, violence usually follows.

In the past few weeks, we have been watching the fall out of what has been dubbed Sokal Squared, the effort by James Lindsay, Helen Pluckrose, and Peter Boghossian to expose the low standards and hateful ideology to which much of the humanities have been in thrall in recent decades. In my response, I highlighted the postmodern assault on epistemology. I said, it has been “the explicit goal of post-modernity to reject reason and evidence: they want a ‘new paradigm’ of knowledge.” During this same period, we also saw a sad episode in US history, in which this rejection of reason and evidence arrested the Democratic Party, as well as the media, academia, Hollywood, and several notable legal institutions, who each marched in quasi-fascistic lock-step in their attempt to eviscerate Brett Kavanaugh, now a Supreme Court Justice. It has been notable after the confirmation how quickly the media—who were nothing less than Orwellian in their complicity—have sought to move on from this ugly affair. They lost, but the toll that the nation had to pay for their struggle, was severe.

This represents a turning point in the culture wars. I watched it play out with a sense of dread and horror. It was mortifying enough to see so many people completely abandon standards of jurisprudence such as burden of proof, or innocent until proven guilty. It was almost amusing at times to watch them disingenuously mount each step of the goal-post treadmill: “It’s not a trial it’s a job interview.” Anyway, it doesn’t really matter if he did it or not: “He got angry! He drank beer! He threw ice in 1985! Look at this yearbook from 1982!”

At times I felt dazed trying to keep up with the mind-bending logic of people who argue only from Machiavellian tactical ends and never from first principles. Thus, within a week, the message went from #BelieveAllWomen to “don’t believe women that Michael Avenatti puts forward.” When there was still a chance it could bring Kavanaugh down, in lieu of corroboration or evidence, the Democrats and their assorted cheerleaders in the media and academia—and even some Republicans—endlessly repeated the phrase “credible testimony.” To quote Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking Fast and Slow: “A reliable way to make people believe in falsehoods is frequent repetition, because familiarity is not easily distinguished from truth. Authoritarian institutions and marketers have always known this fact.” This had all the hallmarks of gaslighting, and it was alarming to see august institutions such as The New Yorker ready to cash in decades of cultural capital for a tawdry political hit job. The Nobel laureate, Paul Krugman, opted to drain away the last dregs of his credibility in an extraordinarily tin-eared column, even by his low standards, which has rightly been taken to task by Quillette already. More alarmingly, this was all done in broad daylight and millions could see it. If I was being optimistic, I’d say it was a moment in which lots of normal people woke up. If I was being pessimistic, I’d say it was a moment in which the left chose a nuclear option that threatens to turn the culture wars into a civil war.

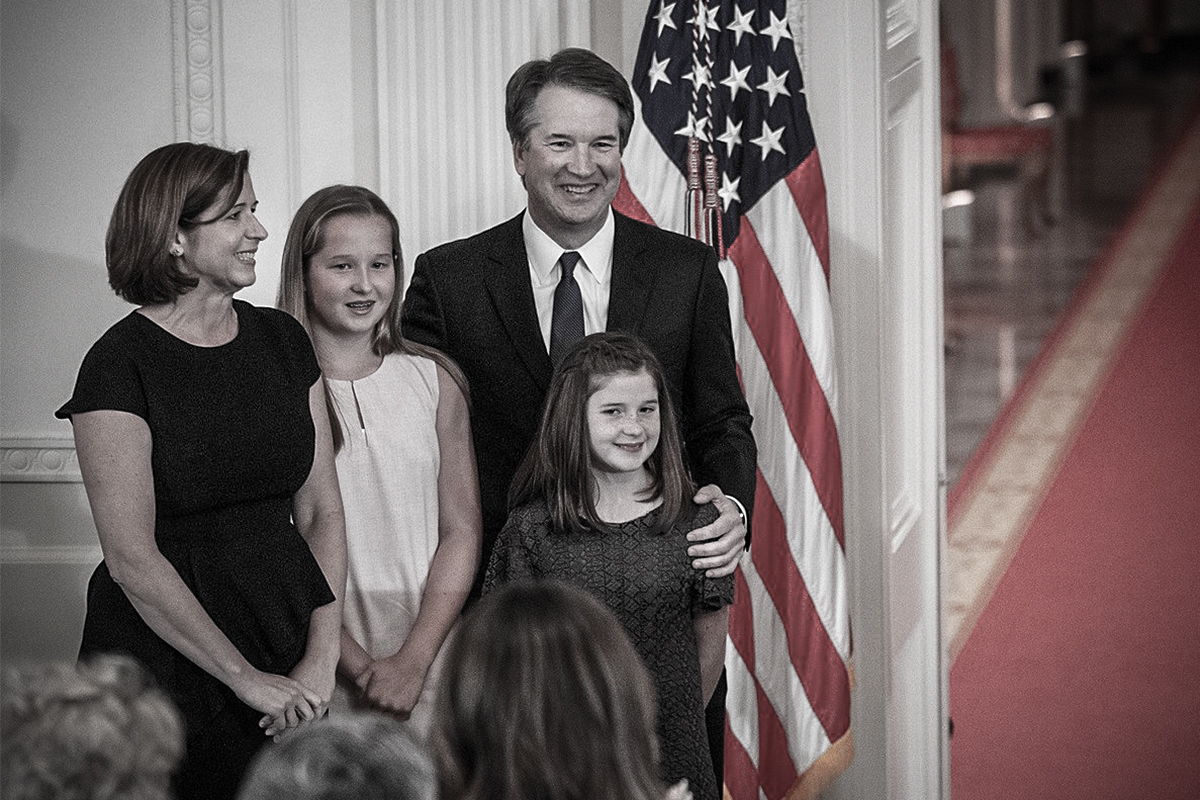

However, the thing that worried me most about the whole episode was something else: the basic inability of those on the left to see Brett Kavanaugh as a human being with a family, friends, and a reputation to uphold. Most normal people saw Kavanaugh on the stand fighting for his life. Personally, I was reminded of John Proctor from Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, a play about the Salem witch trials, who screams “because it’s my name” as he refuses to sign the confession that he has consorted with devils. However, this was not the reaction from thousands of people on the left. To them, Kavanaugh was something else. He was a symbol of the “white male patriarchy.” He was a petulant and spoiled creature of privilege, and an emblem of everything wrong with the US and Western civilization more generally (which, of course, they also despise). To these people, Christine Blasey Ford was not simply a victim, but a symbol of all women: a hero, a martyr, a modern-day saint. To me, as someone who believes that the Western ideal of individualism is a bedrock of our common values, this is terrifying. It marked the moment that the juvenile “Resistance” movement and the genuinely important #MeToo movement coalesced into something resembling the spirit of the French Revolution. Protestors swarmed Senator Ted Cruz and his family in restaurant with chants of “We Believe Survivors!” Whenever a political movement ceases to see people as individuals, and rather sees them as symbols of a class, violence usually follows. In the French Revolution, they famously dealt with the aristocrats by chopping off their heads with the guillotine. In Soviet Russia, on Dec. 27, 1929, Joseph Stalin announced “the liquidation of the Kulaks as a class.” In Nazi Germany, it was of course the Jews who faced genocide. In Uganda, Idi Amin expelled the Asians. In Zimbabwe, Robert Mugabe expelled the whites. There are countless examples throughout history, of what happens when people see other people by their group identity and not as individuals. The rhetoric around Kavanaugh in the past month reached such a fever pitch that these comparisons are warranted. A writer for the “The Late Show with Stephen Colbert” boasted: “I’m glad we ruined Brett Kavanaugh’s life.” And an associate professor from Georgetown wrote the following on her Twitter account: “Look at [this] chorus of entitled white men justifying a serial rapist’s arrogated entitlement…All of them deserve miserable deaths while feminists laugh as they take their last gasps. Bonus: we castrate their corpses and feed them to swine? Yes.” We are still at the stage where such sentiments are considered beyond the pale, but the more disturbing fact is that these people have been whipped into such a frenzy that they are saying such things at all.

As a Shakespeare scholar, I must constantly think about why Shakespeare is relevant to us today. One of the many reasons is that his plays—unlike French Revolutionaries, Soviets, Nazis, or our modern-day friends on the left—always focus on the individual rather than the symbol or archetype. They do not simply see Othello as a Moor, Shylock as a Jew, or Hamlet as a Dane—they register their individual faces and expressions and personalities. One cannot easily generalize about women in Shakespeare’s plays just as one cannot easily generalize about women in real life: Portia is precocious in Merchant of Venice, Rosalind runs rings around the men in As You Like It, Ophelia is fragile in Hamlet, Margaret of Anjou and Joan of Arc in the history plays are fierce generals and warriors respectively. The plays force you to consider these women as individuals. Even when painting with broad brushstrokes, Shakespeare always finds time to zoom in and find individuals in the crowd. Thus, during the scenes of Jack Cade’s rebellion in Henry VI Part 2 we don’t get a nameless mob, we get Dick the Butcher and Smith the Weaver. In Richard III, the two nameless assassins sent to kill George, Duke of Clarence, are given recognizable personalities as one of them comically gets a fit of conscience about his chosen line of work just moments before doing the deed. We cannot think of them as “just assassins,” Shakespeare reminds us that they are people too. Students like to say that this fact makes Shakespeare “relatable,” I prefer to say it is what makes him the most humane of writers. His plays also record the fact that once this basic recognition of a common humanity is lost—as is the case in the more brutal moments of King Lear, Titus Andronicus or the history plays—then endless and vicious cycles of revenge perpetuate.

Western civilization, at least since about Shakespeare’s time, has rested on this notion of the individual as sacrosanct—as against the collective, the group, or the mob. When people have given into the tribal instinct in the past and seen individuals only as symbols of a group or a class, it has resulted in atrocity. We should not think that this cannot happen again. Remember what Douglas Murray said in The Strange Death of Europe: “Everything you love, even the greatest and most cultured civilizations in history, can be swept away by people who are unworthy of them.” And make no mistake, those who are currently stoking the mob’s worst instincts—at this point with naked hatred—are unworthy of Western civilization. They would do well to remember that there are many of us who still believe in individualism, reason and evidence as the cornerstones of that civilization. We aren’t ready to hand the keys to the barbarians at the gates just yet.