Education

Asian-Americans' Unrequited Love of Harvard

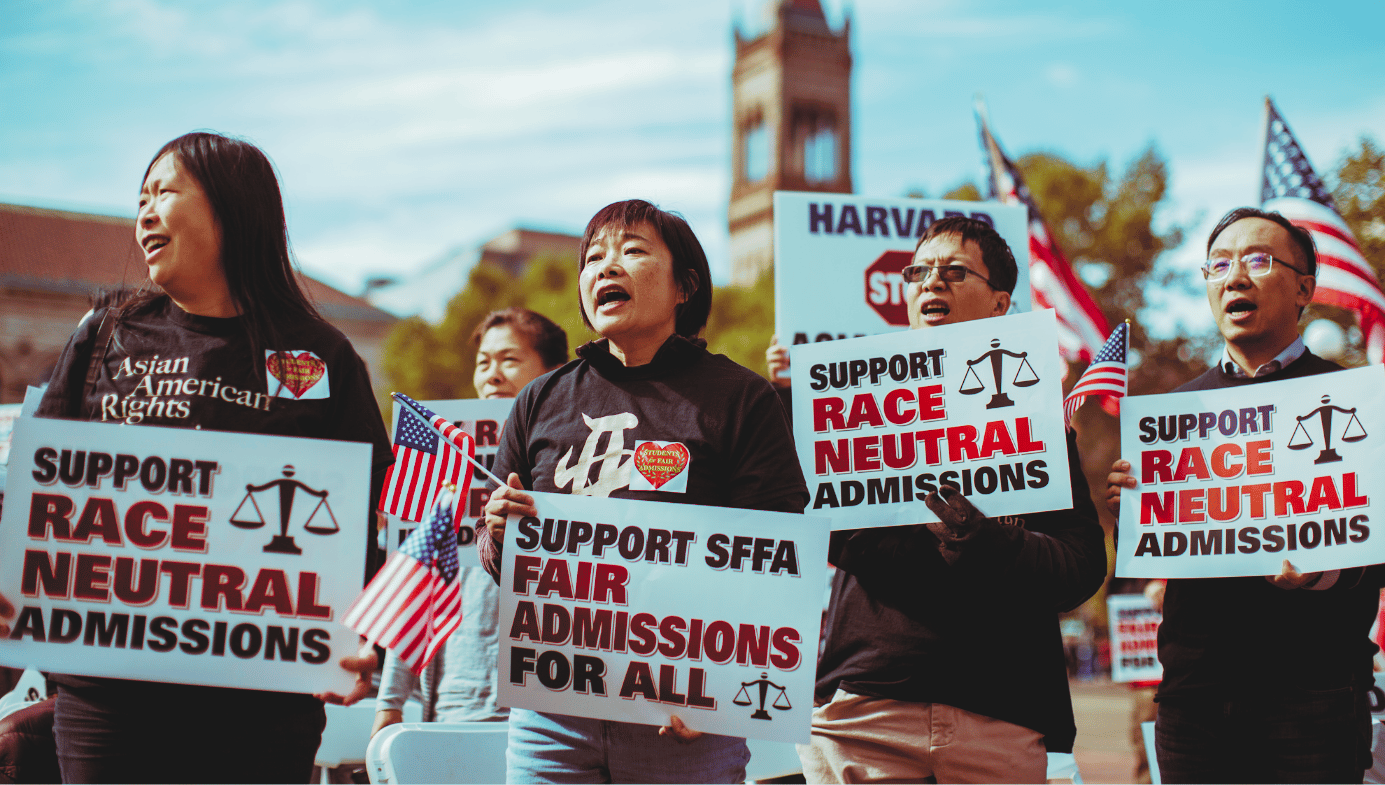

Asian-Americans don’t necessarily think of themselves as “victims” of Harvard’s racist policies. They’re more concerned with the idea of merit—they want their admission to be judged on their resume of accomplishments, not their race.

Harvard is known as the Ivy League’s Ivy. It is toasted as the gold standard, not only in education, but in academic culture—in visibility as the pinnacle of academic achievement in the entire world. It’s the #1 best-endowed school in the world, with a 400-year history that has produced some of the world’s most powerful and influential people of all time.

But to the United States’ 22 million Asian-Americans, Harvard means something even more. Entire industries have been formed to tutor Asian kids to get into Harvard—and Princeton and Yale. Bestselling memoirs like Harvard Girl and Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother have commented on Asian parents’ ceaseless devotion to getting their kids to breathe the rarefied air of Cambridge, Massachusetts. To these Asian parents, deeply committed to ideas of competition and meritocracy, Harvard represents their ultimate prize.

All this power, all this adoration, levelled upon one institution—Harvard is Asian-American culture’s king, and how does it treat its subjects?

“Harvard never accepts Asian guys,” says Kenneth Xu (no relation to the author) says. Xu is a graduate of the ultra-competitive North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics, where he is surrounded by other competitive Asians like him. He grew up in a community in which Harvard’s bias against Asians was well-understood. “Everyone in the local Chinese community knows that the application process is much more competitive for Asians, but I was taught not to complain,” he adds.

But someone did. In April, an Asian-American group called Students for Fair Admission filed a lawsuit against Harvard, alleging that its admissions practices have discriminated against Asian kids for decades. On August 30, the Department of Justice filed a brief in support of Students for Fair Admission. Now, on October 15, the case is slated to go to Massachusetts Federal Court for oral arguments, with the potential to go to the Supreme Court if things get murky.

After Harvard’s admissions documents were released to the public, confirming through its own internal review that an Asian-American is significantly less likely to be accepted than if race were not a factor in his or her admissions process, Asian-Americans across the United States, including Xu, spoke out. “I think I can speak for college admissions consultants when I say that none of us were shocked,” he wrote in the New York Times about the Harvard investigation.

Another Asian-American, J. Cui, wrote: “This is personal to me.” He claims to have been wait-listed from Harvard despite perfect SAT scores, outstanding grades, and a litany of extracurricular leadership. This was while two athletes with far worse credentials got in. The letter is understandably tinged with the bitterness and resentment of someone who feels utterly cheated.

This is bigger than Harvard. Asian-Americans see the Harvard lawsuit as just the first step in the eventual toppling of the entire elite school racket against their race. In April, the Center for Equal Opportunity (a conservative think tank) released a study confirming what has long been common knowledge in the Asian-American community: it’s not just Harvard. Elite schools like MIT, Yale, and Princeton appear to also be discriminating against Asian-Americans in some form, keeping their Asian admissions down to a ratio that reflects what each college believes ought to be an acceptable balance in the racial composition of its students.

Elite colleges’ purposeful suppression of Asian-American admissions—kept to around half of the percentage of Asian-Americans that would be admitted given no racial considerations in the process, according to DOJ documents—has consequences beyond simply that of Harvard’s own campus. Harvard’s suppression creates voids of jealousy that burn within Asian-American communities nationwide. It betrays the ideals of equal treatment and meritocracy that these colleges once helped shape. And it makes Asian-Americans despise themselves for the very thing they can’t change—their race.

* * *

Some Asian-Americans play the elite colleges’ game by its unfair rules, embracing the lottery-ticket feel of a spot by going to amazing lengths to get noticed.

Samuel Dai, a graduate of Princeton High School in Princeton, NJ, knew that his top goal was to get into Princeton, another college implicated in this elite admissions scandal. He quickly and effectively compiled a record of achievement at his high school, becoming the top performer at his Science Bowl team, wining several medals in student achievement, and taking courses at Princeton University even before he graduated from the neighboring high school.

“I knew I was better than other people [who got into Princeton] in terms of what a college student would be,” he says. But then again, he adds, “most of us thought we were the cream of the crop.”

But even stretched to these lengths, Asian kids don’t always—or even usually—get what they deserve. And when they don’t, it can crush them. Dai started having doubts about whether he would get into Princeton as soon as he submitted the application. Suddenly, he saw holes in his resume he previously didn’t think were there. Suddenly, his essay looked less-than-pristine. He developed an “all-or-nothing mentality” towards Princeton—in order to cope, he started thinking, illogically, that “if I stacked it all [on Princeton], I’ll get in.” That is, if he told himself constantly that he was better, that he had no chance of failure, he couldn’t fail.

But he did. On December 18, he received a deferral letter from Princeton’s early-action admissions department. (Princeton has only a minute chance of admitting people into campus after deferring them in the early-admissions stage.) “I went to one of the stairwells, called my best friend, and I started crying … I had a mental breakdown,” Dai says. “Being rejected from your early decision [college] makes you feel like you’re not worth it.”

Maybe he overreacted. But Dai’s experience resonates with Asian-American kids growing up in college-prep hotboxes all over the country. Even when they’re the best, they’re not the best. In fact, they’re still not good enough. That is the signature feeling of the high-achieving Asian elite-school hopefuls.

It gets to the point where some Asians choose to rebel from this college stress culture. There is a group of Asian-Americans at various colleges across America who have started a movement called “Not a Model Minority.” The idea is to defuse stereotypes of every Asian-American being the kind of hardworking, studious, nerdy student that characterizes many perceptions of Asians—including that of admissions counselors.

When I first got to college, I didn’t understand Not a Model Minority. I didn’t understand why Asian-Americans would found an organization that tries to paint them as less achieving than they are perceived. But now I do understand. The “model minority” myth is not helpful to Asians. Instead, it is used by institutions such as Harvard to justify discrimination.

But truly, how distorted, how perverted, must a system be when members of a minority group try to position themselves as less smart and diligent than they actually are? Or how unhealthy can a system be when a student must prove that he isn’t “like the others” of his race in order to have a fighting chance? When a student must learn to renounce his own race and culture?

And yet here we are.

* * *

Harvard and other elite colleges across the United States claim they do not employ any such discriminatory policies. They say they use race in admissions only as a vehicle for a “diverse” student body, not because they dislike Asians or their personalities. That may well be true. Few believe these elite colleges have a truly active animus against Asians. But that doesn’t make their behavior any less insidious.

In denying anti-Asian prejudice, Harvard mentions that their admissions model is guided by the promise of a “diverse” student body. “Harvard remains committed to enrolling diverse classes of students,” said Rachael Dane, a spokeswoman for the university. “To become leaders in our diverse society, students must have the ability to work with people from different backgrounds, life experiences, and perspectives.”

Dane refused to budge on the question of whether or not Harvard should be held accountable for its racial balancing policies. Robert W. Iuliano, senior vice president and general counsel for Harvard University, stated in a letterto the New York Times that: “We will continue to vigorously defend the right of Harvard, and other universities, to seek the educational benefits that come from a class that is diverse on multiple dimensions.” This, then, is Harvard’s justification for applying race-based standards unevenly across various ethnic groups. Diversity.

Harvard and other elite colleges defend the diversity rationale with a peculiar vehemence. They cite the famous affirmative action case, Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, and its successor, Grutter v. Bollinger, as justification enough to give colleges who take government money (Harvard takes $500 million in government money annually) broad authority to implement racial “goals” as they see fit. In particular, they point to the distinction that the Bakke case and its corresponding legal opinion drew between racial “quotas” (disallowed by Bakke) and “goals” (allowed by Bakke). Quotas, the reasoning runs, are hard and fast, while goals are “flexible.” Never mind that Harvard has maintained a rigid 18-19 percent ratio of Asians in its incoming freshmen classes for past ten years—perhaps the opposite of “flexible.”

Nevertheless, Harvard has had its way for the past 30 years. Subjected only to the flimsiest of anti-discrimination standards, and emboldened by reassurances handed down by the highest court in the land, Harvard has been awarded permission to—if we might borrow a word used by a Harvard Law Review article on the subject—sculpt its incoming class to its liking, particularly with respect to race and ethnicity.

Why does Harvard care so much about having the ability to judge people on the basis of their race? The answer lies in the philosophy that undergirds Harvard’s rationale for existence. Harvard believes, as most colleges do, that it is responsible for caretaking and cultivating the next generation of thought leaders and world influencers. They want to midwife a world in which all races are balanced in power and influence, and they feel a responsibility to shepherd this vision of grand racial restructuring—under their own terms and ratios, of course. Their determination? Asians may come to Harvard until they reach about 20 percent of their student body. Then they become “overrepresented” and need to be “balanced.”

Where its arrogance goes too far, however, is now the subject of this lawsuit. Harvard’s penchant for racial balancing has been well documented for decades. According to 30 years of data, Harvard has kept its Asian population artificially low since at least 1990. New evidence from Harvard’s recently released internal reports, however, describes how Harvard manages to justify this kind of discrimination, when the United States Supreme Court so clearly ruled against the use of racial quotas in admissions in Bakke.

Harvard uses several “ratings” to determine who is eventually admitted to the college: academics, extracurriculars, and the “personal” rating are the top three. According to Harvard’s own internal documentation, Asian-Americans fare extraordinarily well on both academics and extracurriculars, suggesting smooth sailing in admissions. However, on the personal rating, which emphasizes subjective evaluations on “likability,” “courage,” and being an “attractive” person, Asians fare extremely poorly. And by Harvard’s own admission to the Department of Justice, it is that “personal” rating that determines selection more than anything else.

So fluky is this discrepancy in the personal rating that the Department of Justice was unable to link these low scores to any observable factors in the applications whatsoever. Their conclusion is rather obvious to the many Asian-Americans across the United States: it must be race. Because we’re “the Model Minority,” the kiss-up minority, the minority that does everything just to get into Harvard. The desperate unrequited love that is easy to reject, because it will keep coming back.

It is increasingly clear to all that Harvard has been lying about its commitment to racial nondiscrimination. They have not only been lying, but they have been getting away with it too—and for a half-century, no less. The effects of this betrayal are real and severe for an Asian-American community that has grown up in its shadow, only to find out that the vision Harvard has for its students is one that excludes them.

* * *

Many Asian students, while disappointed in Harvard, don’t feel the wave of immense rage incidents of injustice can often incite. Instead, they feel a kind of jaded cynicism. “There’re a lot of Asians who are interested in science and math,” says Samuel Dai, who is pursuing a science degree at Carnegie-Mellon University, which wasn’t his first choice. “My resume wasn’t high enough compared to the competition,” he said matter-of-factly.

The betrayal doesn’t come simply from the discrimination itself but rather the messaging Harvard has sent out their entire waking adult lives: the idea that Harvard is committed to facilitate the entry of a “diverse” class of students—which they didn’t realize meant exclusivity rather than inclusivity in their case. Harvard’s lofty goals were dishonest; their claims to diversity were hypocritical.

It is not even that these Asian-Americans are only fighting for more representation in elite colleges, though this is the catalyzing incident. They want to live in a fair society. One that accurately represents the promise of the American Dream—that if you work hard, there’s nothing stopping you from achieving your ambitions. This dream is presently compromized—and worse yet, it is compromized by the very institutions that claim to exemplify it.

“The worst part is, they’re not even setting standards based on things we can change about ourselves,” says Liu Ruohong. Ruohong is an Asian-American mother and a member of an all-Asian-American group called Association for Education Fairness, which campaigns for equal treatment in education. “We’ve got to stand up for our children.”

So if educational attainment is such a big issue in the Asian-American community, and Asian-Americans have known about discrimination for so long, why has nothing been done about it?

To this question, the Asian-Americans admit they have no easy answers. I spoke with Eva Guo, the leader of the Association for Education Fairness, to find out her perspective. Guo, whose organization is devoted to fighting unmeritocratic and unfair admissions policies in high schools, believes that part of the answer lies in Asian-Americans’ own mentality. “It’s something we need to work on,” she admits. “Asian-Americans aren’t very good at being loud. But we need to make our voice heard.” Asian-American protest and political activism doesn’t have as much precedent as that of Black and Hispanic Americans.

But the lack of exposure cannot be completely blamed on Asian-Americans themselves. Put simply, stories such as these are often either ignored or misunderstood by the national media. First of all, Asian-American views on issues are not often featured on hot political topics. The Pew Research Center’s study of views on immigration, racial discrimination, and health care include breakdowns to white, black, and Hispanic Americans, but exclude Asian-American viewpoints, even though Asian-Americans are projected to be the nation’s largest immigrant group by 2050. Typical discussions of racial disparities focus largely on black and white Americans (and, to a lesser extent, Hispanics), but almost never train their eyes on Asian-Americans.

Therefore, discussion of the Asian-American experience too often veers into coat-tailing “black experience” stories or, more especially, a typical “Person of Color” narrative. Person of Color narratives, which are currently fashionable, especially in mainstream journalism and academia, tend to emphasize victimhood and oppression, which. This could be construed as a frame for the experiences of Asian-Americans in admissions, but is not a helpful way of understanding the issue.

Asian-Americans don’t necessarily think of themselves as “victims” of Harvard’s racist policies. They’re more concerned with the idea of merit—they want their admission to be judged on their resume of accomplishments, not their race. They don’t feel “oppressed” by the system or trapped in a zero-sum world—after all, college isn’t all that the world has to offer. Rather, they feel indignant and cheated.

Their betrayal by Harvard is not meant to be an all-encompassing The System Is Against Us kind of story, and it would be a mistake to understand it that way. Rather, it should be seen clearly for what it is—a fixable problem that hasn’t been fixed. Governments can do their part by denying their $500 million of federal funding to Harvard and other elite colleges unless they comply with explicit non-racial-balancing provisions. The Department of Justice has already sided with the Asian-American group, Students For Fair Admissions, in its current lawsuit. Harvard can do its part by making its admissions system more honest, transparent, and meritocratic, and publicizing those changes in the name of public accountability. And ordinary Americans can do their part by seeing through the false promise of “holistic admissions,” which is just another tool universities employ to admit according to their personal beliefs and prejudices rather than on merit.

But Asian-Americans, too, have a part to play in this drama over their educational futures. For a start, they should reject the elitism of schools like Harvard. The more they try to force their way in, the harder Harvard resists. They need to say to their children: “Go to the best college you can, but don’t think it defines your life.” They need learn how to walk away from the idea that an elitist education is the only way in. This may be true in China, where universities are in short supply and one of the only ways one can enter the respected ranks of business and the Communist Party. But it is not true in America, where the country’s higher education infrastructure is arguably the best in the world. Americans have options within and beyond college that allow people of any race to rise above their station.

If Asian-Americans are going to win this noble fight for meritocracy and equal treatment in admissions, they need to learn to fight, not only for themselves and their own interests, but to take their lived experience and understand it through the ideals of the American Dream. And then to raise their voice. Loud and clear for all in ivy-soaked Cambridge to hear.