Alex Jones

Alex Jones Was Victimized by One Oligopoly. But He Perpetuated Another

We must be the protectors of our own free speech, and habitually speak out not just against the tech giants, but also against populist gurus.

This month, Twitter joined Apple, Facebook, Spotify and YouTube in banning the popular right-wing conspiracy theorist Alex Jones from its platform. Like the other bans, Twitter’s decision was announced as a fait accompli, with opaque justifications ranging from “hate speech” to “abusive behavior.”

The seemingly arbitrary nature of these bans has raised fears from all political quarters. Alexis Madrigal, writing in The Atlantic, cited the development as proof that “these platforms have tremendous power, they have hardly begun to use it, and it’s not clear how anyone would stop them from doing so.” His sentiments were echoed by Ben Shapiro in the National Review, who expressed alarm at “social-media arbiters suddenly deciding that vague ‘hate speech’ standards ought to govern our common spaces.”

Even some on the left displayed concern. Steve Coll wrote in the New Yorkerthat “practices that marginalize the unconventional right will also marginalize the unconventional left,” and argued that we must defend even “awful speakers” in the interests of protecting free speech. Ben Wizner of the American Civil Liberties Union described the tech giants’ behavior as “worrisome,” and suggested the policies used to justify the bans could be “misused and abused.”

It is indeed worrying that some corporations now have the power to restrict how much influence someone can have on the marketplace of ideas. But what is more worrying, and what few people seem to be considering, is how Alex Jones was able to gain such influence in the first place. In my view, the ideological forces responsible for his rise are a greater threat to free speech than the corporate forces responsible for his “fall.” Principled defenders of free speech would therefore be unwise to rail against the former while ignoring the latter.

The reason tech giants like Twitter and Facebook are able to exert such worrying control over our speech is that they comprise an oligopoly, with no significant competitors. Such oligopolies tend to form in business due to the Matthew principle, which holds that advantage begets further advantage. If Facebook manages to get all your friends to use it, then Facebook’s chances of getting you to use it are drastically increased, because you want to be connected with your friends. This particular example of the Matthew principle is known as a “network effect.”

Crucially, network effects don’t just apply to free market economies; they also apply to the free market of ideas. Concepts that get more exposure will get more exposure. This virality can cause the arena of debate to quickly become dominated by an “oligopoly” of perspectives.

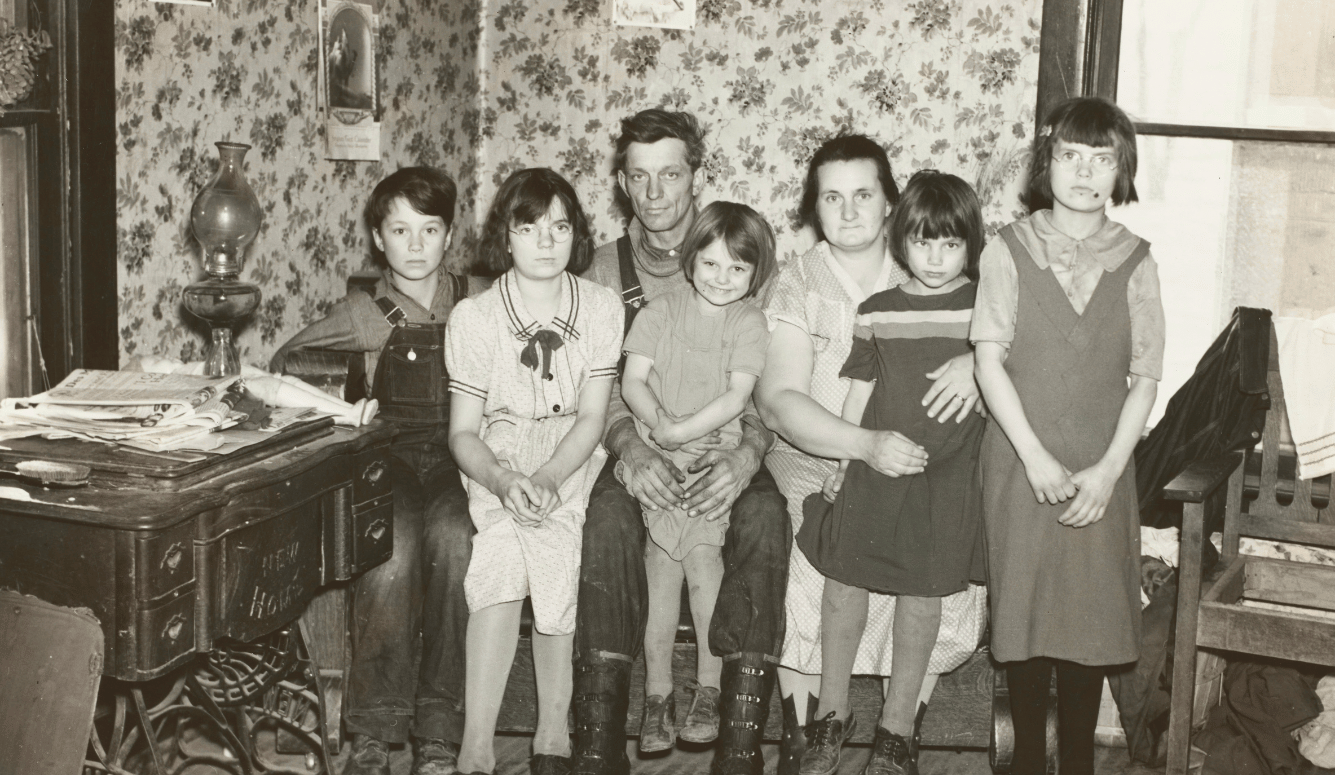

Hence, just as the free market of infotech is now dictated by the Googles and Facebooks of the world, so too has the free market of ideas come to be controlled by a few political narratives, particularly the social-justice narrative of the left and the anti-globalism narrative of the right. The social-justice left dominates among the cultural elite, including the mainstream media, the literati, the tech industry, Hollywood and academia. The anti-globalist right, meanwhile, is popular among the general public, as evidenced by the success of the U.K.’s Brexit campaign, and the election of Donald Trump in the U.S. and a host of nativist parties in Europe, such as Poland’s Law and Justice and Italy’s Five Star movement.

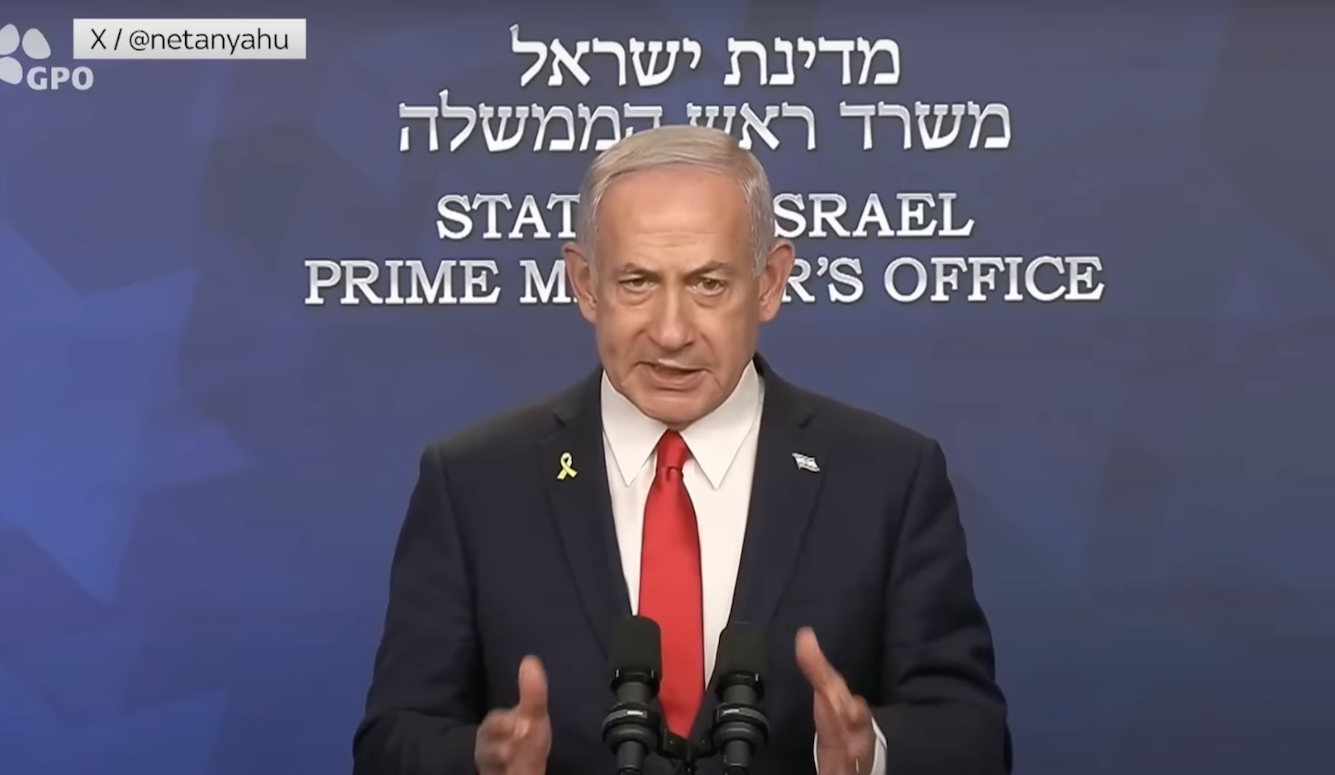

The story of Alex Jones brings these two strands together, because he has fueled the surge of right-wing populism in large part by leveraging the power of tech oligopolies. Far from being a “fringe” figure (as he is often portrayed), Jones is a key conduit of a popular narrative, broadcasting to over 3.6 million unique online monthly viewers, and apparently having the ear of the American president (which may help explain why baseless conspiracy theories about a “deep state” keep circulating around the White House). Jones, in short, is an ambassador for one half of an ideological oligopoly, which is just as hostile to competition as the tech oligopoly.

But how could this be? To some, the very idea of an oligopoly on ideas may seem bizarre; we are all free to believe whatever we wish. Unfortunately, our brains did not evolve to understand the world but to survive it. Reality is software that doesn’t run well on our mental hardware, unless the display resolution is minimized. We therefore seek out stories, not because they are true, but because they reduce the incomprehensible into that which is comprehensible, giving us a counterfeit of truth whose elegant simplicity makes it seem truer than actual, authentic truth.

A typical mental schematic that allows us to do this is the Karpman drama triangle, which divides people into victims, oppressors and rescuers. We have a tendency to view events using this cognitive compression algorithm because it simplifies reality into drama, offering not just clarity to the confused, but also belonging to the lonely, purpose to the aimless, battle to the bored, and scapegoats to the vindictive.

The social-justice left and anti-globalist right both fully embrace the Karpman drama triangle as a lens for looking at the world. In the social-justice narrative, minorities are the victims, the white patriarchy is the oppressor, and the social-justice activists are the rescuers. In the populist-right narrative, the silent oppressed majorities constitute the victims, the globalist elites are the oppressors, and certain maverick figures (such as Alex Jones and Donald Trump) are the rescuers.

Anyone who doesn’t neatly fit into a corner of the drama triangles will either be shoehorned in, or ignored. This simplification of reality into a dramatic struggle is what makes these narratives so hostile to competing ideas; disagreement is viewed not as a legitimate difference of opinion, but as an attempt at oppression. And when you feel you are being oppressed, you can justify the use of any tactic to fight it.

This is why we see those on the social-justice left using their influence in media, academia and the tech industry to forcefully suffocate the expression of alternative viewpoints — including by the firing of those with different opinions, or by shouting them down at universities, or by physically assaulting them.

And on the populist right, we see similar tactics of intimidation and ostracism, whether through the harassment of climate scientists, the denial of security clearance to former CIA directors who won’t toe the president’s line, or the demonization of conservative pundits who fall out of love with Donald Trump.

Alex Jones himself has been among the biggest instigators of right-wing intimidation. For years, he has concocted lies about those who don’t agree with his narrative, claiming they are agents of foreign governments, literal demons, or child molesters. He also has suggested that his followers should take up arms against the nonbelievers (which is why Twitter suspended him), and his conspiracy theories have led his followers to harass and threaten people with violence.

Unfortunately, this sometimes has led to actual violence. In 2009, Richard Poplawski, who regularly commented on Jones’ Infowars website, and cross-posted many of Jones’ articles on neo-Nazi forums, killed three police officers with an AK-47. The following year, Byron Williams, who cited Jones as an influence on his thinking, engaged in a firefight with police, injuring two. A year later, Jared Lee Loughner, who counted among his favorite documentary films the Jones-produced Loose Change, attempted to assassinate U.S. representative Gabrielle Giffords, injuring her and 12 other people, and killing six. Later that year, Oscar Ortega, having watched the Jones-produced film The Obama Deception, shot at the White House. In 2014, Jerad and Amanda Miller, both regular commenters on Jones’ Infowarssite, posted anti-government videos and then went on a shooting spree, killing three before dying themselves. Two years later, Edgar Maddison Welch, convinced by the Pizzagate conspiracy theory pushed by Jones, shot up the Comet Ping Pong pizza parlor in Washington D.C.

It is difficult to determine how much influence Jones’ views had on these atrocities. However, the link between hateful Infowars-style rhetoric on Facebook and hate crime was explored by an extensive study of 3,335 attacks against refugees in Germany, where the populist right-wing Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) has developed a major web presence. The study found that such attacks were strongly predicted by social media use: Wherever per-person Facebook use rose to one standard deviation above the national average, attacks on refugees increased by an average of 50 percent.

Violence is the most direct and dramatic way that the social-justice left and anti-globalist right censor speech. But it is just one tactic among many — including threats, doxings, firings, harassment, mobbings and demonization. This is why the radical left and right, led by demagogues like Alex Jones, represent an even greater threat to our speech than the tech giants. They are gradually turning the free market of ideas into a kind of ongoing hostage crisis, by which people are either afraid to speak their minds, or are doomed to have their words interpreted in the worst possible way when they do so.

I don’t want to make the same mistakes as Jones, so I should emphasize that these drama triangles that are so hostile to free expression weren’t engineered by a secret cabal of ideologues or tech CEOs. They arose organically, regulated only by laws of nature such as the Matthew principle, network effects, and the public’s demand for easy answers. Sure, there are individual Facebook employees who may be interested in pushing a political agenda, but Facebook as a business is not. It seeks to do what is best for profits: making its platform as inviting to as many people as possible.

That’s not to say it is successful in this venture. Corporations are ill-equipped to police the information traffic of millions of users, which is why they frequently get things wrong (such as censoring the Declaration of Independence as hate speech). And even when they get things “right,” they usually only end up benefiting their targets — as evidenced by the fact that, in the wake of Jones’ de-platforming by the major media companies, his Infowars app surged up the download charts. The greatest endorsement a conspiracy theorist can receive is censorship by authority figures. It’s a golden opportunity to portray themselves as the victim in their Karpman drama triangle.

So, if we can’t rely on powerful organizations such as governments or corporations to protect our voices from mob rule, what then?

In my view, it leaves only one real option: We must be the protectors of our own free speech, and habitually speak out not just against designated “oppressors” like the tech giants, but also against designated “victims” and “rescuers,” like Alex Jones, who seek to oppress by dehumanizing others as oppressors. And we must do all this without constructing our own drama triangle of oppression, or else we’ll become part of the very problem we seek to solve.

John Stuart Mill believed that in a free market of ideas, good ideas would naturally trump bad ones. But experience has shown that this won’t happen unless the marketplace is populated by those who actively seek truth and openness. Free speech is the foundation of all other rights. It is the seed of innovation, the wheel of progress, the space to breathe. It must therefore be protected at all costs — including, at times such as these, from itself.